Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 5, No. 1, 2003

The Curricular Practice of a Work-Competency Model

for Adult Higher Education

Etty Haydeé Estévez

simyc@rtn.uson.mx

Departamento de Psicología y Ciencias de la Comunicación

Universidad de Sonora

Rosales y Luis Encinas, Col. Centro

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

Luz Delia Acedo Félix

luz_acedo@hotmail.com

Subdirección de Fomento Institucional

Secretaría de Educación y Cultura

Guerrero y Sonora, Col. Centro, 83000

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

María Guadalupe Bojórquez Ramírez

magualu2000@hotmail.com

Salvador Alvarado 109, Col. Pitic

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

Beatriz Eugenia Corona Martínez

becosa@hotmail.com

Instituto Soria

Manuel González 217 Sur,

Col. Centro, 83000

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

Carmen Virginia García Acosta

krmen@villa1.uno.mx

Departamento de Idiomas

Universidad del Noroeste

Km. 6 Carretera Internacional a Nogales

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

Miguel Ángel Guerrero Badilla

miguel@larrea.edu.mx

Sección Secundaria

Colegio Larrea

Juan G. Cabral y Justo Sierra, Col. Pitic

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

Graciela Guillén Álvarez

graciel89@hotmail.com

Hospital Dr. Carlos Nava Muñoz

Instituto de Higiene Mental

Rosales 182, Col. Centro, 83000

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

Bertha Alicia Loroña García

alorg@rtn.uson.mx

Coordinación de Servicio Social

Colegio de Bachilleres, plantel Prof. Ernesto López Riesgo

Veracruz Final s/n, Col. Country Club

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

Jesús Enrique Mungarro Matus

emungarro@yahoo.com

Coordinación de Deportes

Colegio Larrea

Juan G. Cabral y Justo Sierra, Col. Pitic

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

Hisa Margarita Tirado Hamasaki

hisa_margarita@yahoo.com.mx

Coordinación de Informática y Telecomunicaciones, Gerencia Regional Noroeste

Comisión Nacional del Agua

Comonfort y Ave. Cultura, Edificio México, 5to. piso, Col. Villa de Seris

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

(Received: October 16, 2002;

accepted for publishing: March 2, 2003)

Abstract

The purpose of this research was to get to know the true curriculum of the Northwestern University’s Get Ahead, a special undergraduate program based on the work competencies model and aimed at adults already in the workforce. The goal was to back up the curricular improvement of an educational alternative unique of its kind in Sonora (Mexico). The methodology of Estevez and Fimbres (1998) was used for the formal curriculum analysis and its comparison with the real curriculum from the perspective of its protagonists: teachers and students. The curriculum’s internal and external sources were analyzed in order to define the instruments and variables, and to interpret the results. We concluded that the teachers showed that the teachers were more up to date than the students in regard to disciplinary topics. However, they lack adequate teaching strategies to make an impact on students’ learning process. Moreover, neither teachers nor students are familiar with the competence model, nor do teachers apply a diagnostic examination to determine their students’ competency at the beginning of the course. This indicates that the formal curriculum is distant from the real curriculum.

Keywords: Curriculum development, competency-based curriculum, curriculum evaluation.

Introduction

This paper presents the results of a research project designed to ascertain the practice of two undergraduate curriculums, which were designed under a model of “standards of work competencies” to serve working adults. Selected as objects of study were curriculums for the degrees in Business Administration (BBA) and Certified Public Accountant (CPA) in the Get Ahead program of Northwestern University, located in the state of Sonora (Mexico). Analyzed were both the formal internal aspect and the practical or real curriculum, based on a methodology of curriculum design and evaluation (Estevez and Fimbres, 1998; Estevez, Plancarte, Rovira, Carreon, War, Yeomans and Lopez, 2001) which takes into account the various sources (Casarini, 1999) of curriculum development (Stenhouse, 1991). The result of an analysis of the formal curriculum was compared with the analysis of curriculum practices, the latter outcome based on information provided by students and teachers. We sought to know how students and teachers understand the study plans and programs, and how the formal curriculum is implemented under the model of work competencies.

In the first part of this article the project of the BBA and CPA majors are described and related with some concepts and experience regarding education based on work competencies. Later on there are reflections about curriculum and curricular-source concepts which support and explain the methodology used in this study.

In the subtitle of the method the way the instruments were produced based on hypotheses is explained, plus variables and indicators were inferred from the analysis of curricular sources related with the curriculums, an object of this investigation. Finally, there is presented an analysis of the results and the conclusions, which are understood as an approach to the description of the curriculums mentioned.

1. The Get Ahead program and competency-based education

The Get Ahead program of Northwestern University (UNO) was established in 1997 as an innovative alternative that offers adults over 25, who for various reasons, never attended college, or did not get a degree, the opportunity to pursue graduate studies. At the time this study was done, the first class had not been graduated.

The program is described as an educational offer to give a segment of the economically-active population, by means of an institutional program, an opportunity to get a certificate that will provide backing for their knowledge, skills and abilities. It should be emphasized that in Sonora there is no other upper-level program offering an alternative designed for adults.

According to the project for the creation of the Get Ahead program for the BBA and CPA degrees, the following characteristics are conspicuous:

- Each UNO degree program contains 41 subjects, in contrast to traditional plans consisting of 58 subjects for the BBA and 61 for the CPA.

- Each provides a total of 300 credits, divided between hours of practice and hours of theory. The practice of students in their job or employment is considered to lie within the framework of competencies, which supports reducing the number of materials as compared with traditional programs.

- The student will endorse or validate the skills and competencies she already has, and which are products of her work experience.

- The program establishes a methodology for equivalencies, identification and certification of the skills of students entering BBA and CPA degree programs.

- The program establishes a theoretical framework for education based on work competencies; this framework supports the educational model for Get Ahead, as well as the way it should be implemented. Its main hypotheses are: production processes that require people who can adapt to different forms of work organization; the achievement of competencies involves emphasizing the importance of learning rather than consumables; flexible curriculums are required to be organized into modules based on the Standardized System of Labor Competency; the link with the productive sector is necessary for the creation of articulated learning environments; the model seeks to develop the capacity for innovation, adaptation and continuous learning.

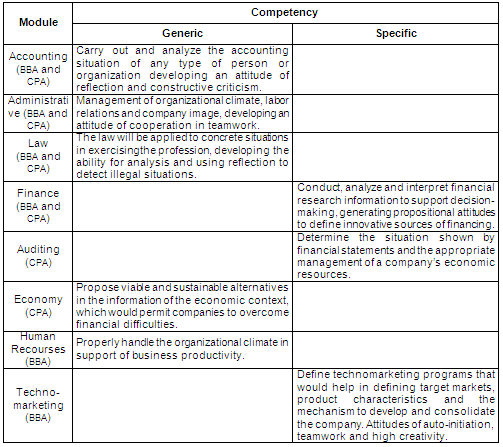

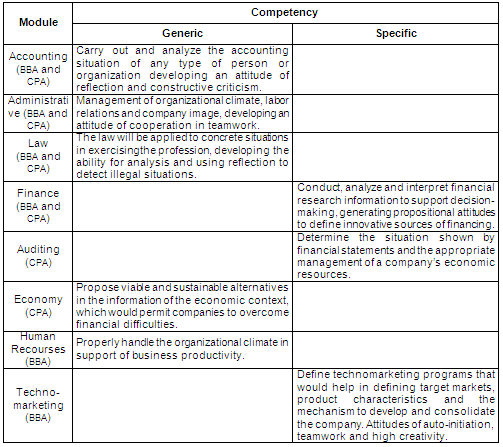

- It specifies general competencies to be developed while enrolled in each work competency module. The following table contains a summary of the competencies established in the curriculum modules (grouping of materials by areas of competency). A great part of these, as we will indicate, are shared by both degree programs, although taught by means of a different number of subjects:

Table 1. Summary of BBA and CPA competencies

The curricular models designed based on the identification of professional competencies and labors, as the case of Get Ahead, have gained their great relevancy for several reasons. First, because it focuses the efforts of economic and social development on the recovery of resources and the human capacity to build development. Also because this approach seems to respond better than many others to the need to find a point of convergence between education and employment. Not only does it have to do with creating more jobs, but also with the fact that the ability of each person is critical for his employability. Finally, because the competencies approach adapts to the need for change, characteristic of contemporary society since it is a dynamic concept that prints emphasis and value on the human capacity to innovate, to face and manage change, preparing for it instead of waiting passively (Ducci, 1997).

Because of all the above, great emphasis has been given to competency-based educational programs, through which is sought the intersection of “multiple sets of skills, abilities, knowledge and attitudes required for optimal performance in a particular occupation or productive function” (Ibarra, 1997, p. 82). This definition of competency coincides with the concept present in the theoretical foundation for the formal curriculum of the Get Ahead program.

According to the specialized literature in this field and with the formal curriculum of Get Ahead, competency-based education cannot be limited to a traditional paradigm. That is, education cannot be centered in the classroom; there must be sought a combination of different learning strategies where participants seek the solution of the problem, and the teacher functions as guide or facilitator. Furthermore, these strategies need to be flexible in order to provide the student with a free advancement in knowledge in an individual manner, an aspect also noted in the formal curriculum of Get Ahead.

In countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay and Mexico there have been set in motion begun training and certification models having the goal of developing mechanisms that will improve the worker’s job skills. In the case of Mexico, there is a training and certification body called the Council for the Standardization of Labor Competencies (CONOCER, its acronym in Spanish). It is composed of representatives from various economic and business sectors in the country. This agency defines labor competency as an individual productive ability, measured in terms of performance in a given employment context, and not simply knowledge, skills and attitudes. The latter elements are considered necessary, but are not sufficient in themselves to ensure effective performance (CONOCER, 1998). The Get Ahead program supports the theoretical framework and justification as determined by the CONOCER.

In Mexico, the curricular model based on work competencies is being practiced in the junior high and upper levels (the CONALEP model, for example) of teaching. The latter system is practiced predominantly in institutions belonging to the subsystem and technological education and in some public universities, such as the University of Guadalajara, the country’s second largest (OIT, 1997). Although there are no studies that establish precisely, in quantitative and qualitative terms, a panoramic diagnosis for the use of this model in Mexico’s educational institutions, there are elements to establish, as an analytical hypothesis, that there is a current tendency to adopt this model in its different variants, in an important part of our country’s higher-education institutions.

2. Curriculum development and the underlying sources

While the curriculum is a polysemantic concept, thinking about it in terms of “curriculum development” as proposed by Stenhouse (1991), allowed us to support theoretically the design of this research, as well as to orient our reflection on its performance. Curriculum development is a concept that unites the three dimensions of curriculum—the formal proposal, its practice and its latent aspects, while explaining the curriculum as a project seeking to communicate the principles and essential features of an educational purpose, essentially characterized by its openness to critical discussion and its possibility of being effectively transferred into practice (Stenhouse, 1991). How, in the practices and ideas of teachers and students, can there be expressed the effect of various external sources underlying a curriculum for adult education based on a work-competency model? In other words, is the curriculum practiced in close relation to the students’ socio-professional and labor reality? What are the work practices that impede a rapprochement between the curriculum and its implementation? These are some of the most important questions that motivated this research; we sought an answer supported by the hypothesis that the central problem of curriculum studies, according to Stenhouse, is the gap between our ideas and aspirations and our efforts to make them operational. Curriculum development is understood as a process of constant deliberation, as a form of work and collaboration so as to experience a project in practice, where the teacher is the central figure in the implementation and modification of curricular intentions.

The curriculum therefore has two functions: dynamism and flexibility. Based on these, there is a search for a way to strike a balance between the formal curriculum, the hidden curriculum and the way the curriculum is made real (real curriculum), so as to allow the establishment of a balance between non-formal education policies translated as guidelines, and models of social relationships, as well as the rest of the behaviors and processes involved in the educational task.

This study focuses on the analysis of the internal curriculum’s source, which is understood as the information generated from the processes and results of curriculum development, and is part of a more general and inclusive concept called curriculum sources (Casarini, 1999), according to which there are a number of sources both internal and external to the curriculum; these together contribute to its foundation and justification. Therefore, the internal source analysis was performed taking into account external sources, understood as socio-cultural, epistemological, professional-occupational and psychopedagogical reflections; from these are constructed principles to guide both curriculum design and its development and evaluation (Casarini, 1999). According to the proposals of Estevez and Fimbres (1998), curriculum sources require a final integrative reading to establish their interrelationships, and based on that, to evaluate and establish the general orientation of an educational program.

3. Methodology

With the purpose of exploring curriculum more deeply, the proposal of Estevez and Fimbres (1998) was used for this study, since, because it is general and flexible, it could be adapted to different curriculum models. In the case of the competency model, the outflow profiles were expressed by integrating knowledge (theoretical knowledge), skills (practical knowledge) and attitudes.

The methodology employed proposes as a first step in the evaluation of a curriculum, the systematization of information pertaining to what are known as external and internal sources; later, from the information obtained, there are inferred the type of knowledge, skills and attitudes (or in an integrated way in terms of general skills) which students must developed, as well as those educational contents they should discard because of obsolescence and social irrelevance. Furthermore, the analysis of curriculum sources can be inferred in the psychopedagogical approach and appropriate teaching methods to encourage the practice of a particular curriculum (Estevez and Fimbres, l998).

In the present case, the curriculum evaluation methodology was adapted and applied in the following manner:

- First, the general competencies it was desired to promote were identified in the formal curriculum.

- Later, outside sources were analyzed by documentary research, so that the research team could have an updated framework of reference to study: a) the linkage of the curriculum with the labor/professional world; b) the degree of update concerning the disciplinary content in the real curriculum; and c) the appropriateness of the teaching methods used in the context of a competency model.

- Based on the above, the variables and indicators were established, and instruments were designed for obtaining information about the practice of the curriculums under study.

3.1. Analysis of the sources

To study the sources, the research team was organized into four groups as follows: socio-professional source, psychopedagogical source, epistemological source, and internal source (real and formal curriculum). In the case of the first three, each group conducted an investigation, basically documentary, on the current requirements for the BBA and CPA training related with their source. From this emerged the hypotheses, variables and indicators (see Annexes 1, 2 and 3.)

The documentary study of the internal source was treated differently, and was conducted in two areas: 1) contextual aspects of the real curriculum, which consisted in gathering statistical data on the populations studied, class schedules and locations of groups; 2) formal curriculum, for which was used the methodological guide proposed by Estevez and Fimbres (1998), obtaining as a result an analysis of the documents containing the above curriculums (see a summarized version in the first paragraph of this article.)

3.2. Study population and instruments

To achieve an empirical approach to the real curriculums, there was established as the study population all students (173) and teachers (22) of the CPA and Business Administration degree programs who were participating in the Get Ahead program during the 2002 January-March quarter. Because of the size of the population, it was decided to apply a census in both cases.

The questionnaire was administered to 22 teachers and 150 students (nearly 90% of the population was considered a census). The students were enrolled in various quarters, and the 22 teachers surveyed work part-time.

According to the curriculum evaluation methodology adopted, questions were formulated for students’ and teachers’ questionnaires (see Annexes 4 and 5). Most of these were based on the hypotheses, variables and indicators established for each curricular source (see Annexes 1, 2 and 3); in some points there were established questions common to both questionnaires, in order to make a comparative analysis.

The questions designed were mostly of a closed type, with some open. The closed questions were of a dichotomous type and others with several possible answers. For the teachers’ questionnaire (questions 2, 16 and 17) and that of the students (question 5) there was taken as a reference the Standard Questionnaire for the Study of Graduates (National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education [ANUIES], 1998). Once the questionnaires had been developed, they were validated by experts in the disciplines and professions. Also applied was a pilot examination for teachers who were not teaching courses this quarter, and students who were temporarily out of the program. The questionnaires were applied without misgivings.

The statistical processing of the results was carried out with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 8.0 (SPSS).

4. Results

The following are the results and reflections on some of the most relevant findings of this study about the practice of two BA programs of the Get Ahead program. The discussion also includes the curriculums of both degree programs, while representing their formal curriculums. The following subtitle refers mainly to “General Information” on the questionnaire (an item not included in the Annex hypotheses). Its purpose was to provide some characteristics of the population studied, as an initial frame of reference. Under the subsequent subtitles are analyzed the results supported by the concept of curriculum sources, understood as interlinked and juxtaposed aspects of the same reality (Estevez and Fimbres, 1998). The second subtitle refers to the epistemological/disciplinary source (Annex 1), the third refers primarily to the psychopedagogical source (Annex 2), and the last emphasizes the professional/ labor source (Annex 3).

4.1. Socio-demographic profile and academic background

The study population was mainly composed (72.7%) of students of the Bachelor’s Degree in Business Administration; the rest (27.3%) were studying accounting. More than half the students surveyed (51%) are women, 50 of whom study in the BBA program. Of the 68 men surveyed, 15 are studying accounting, and 53 are in the BBA.

More than half the students (53.7%) were married, 42% said they were single, while about 4% described themselves as divorced or widowed.

In applying the questionnaires it was found that, except for 4.7% of the those who were unemployed at the time of the study, most work in different industries. There were employees of private businesses and the government, commissioners, assistants, technicians, sales executives, secretaries, administrative assistants and accountants. About 11% of those surveyed work as officials, administrators, coordinators, directors, managers or owners of public or private companies.

The fact that most of the program’s students are economically active supports its character, since it offers an option for those adults who, for various reasons, did not get their Bachelor's degree (52% of the cases) or never went to college (48 %).

It is important to note that 36% of those who did not finish college reported having completed between 25% and 50% of the courses needed to graduate before entering the Get Ahead program, while 23% had complete 76% to 100% of such courses in previous studies. As for the year of high school graduation, 21% of the students finished between 1980 and 1989, compared with the 60% who were graduated during the nineties.

One of the requirements for admission to the program is that the student be more than 25 years of age. However, we found that 16 students (11%) did not comply with this requisite. Regarding the students’ average age, 55% were between 26 and 35, 31% were between 36 and 45, and only 4% were over 45 years old.

4.2. Disciplinary Update

Vis-à-vis the factor most important for generating wealth in the new economy, 20% of students considered it to be strategic planning; 16%, professional development; and 13%, the development aspect of knowledge and innovation systems. As for the teachers, 18% agreed on strategic planning and professional development, while 14% said that developing knowledge and cultivating creativity are more important.

We must mention that there are answers considered acceptable in keeping with the established hypothesis (see Annex 1), according to which, the current economy creates a new system by which to generate this, based on information and production of new knowledge (Picazo and Martinez, 1999). In this case, the response options considered successful are: knowledge development, openness and flexibility of thinking, information management, strategic planning, and cultivation of creativity.

Therefore, when reviewing the percentages of the responses, we observed that most students considered some aspects to be of little relevance, not part of the ideal scenario for the present and future economy; the inference is that there is retained an economic outlook tied to the traditional. Teachers showed a broader perspective on the subject by marking three of the five possible options, indicating that they have are more up to date on the subject of wealth creation.

Among the strategic factors that would give competitive advantages in an organization, 22% of the students mentioned personnel training; 16%, the aspect of competency; and 15%, the aspect of products. Teachers agreed with students about personnel training, 24%; while 17% identified competency and products as strategic, and 12% of teachers surveyed were of the opinion that the factor of the client’s mind was strategic. In agreement with the hypothesis that says we operate in a macro context that radically modifies the traditional schemes economically, politically and socially, marking significantly the level of competition among firms, the responses considered acceptable are: competency, the client’s mind, products, and the environment.

The students were observed to have a vision of the future similar to the trends of the new economy; about half the answers have to do with the new proposed approach, although the other half reflects the traditional practices deeply rooted in these degree programs. The preceding indicates that they know the current situation prevailing in companies, but are not fully convinced that we live transformations that would restructure the policy and the economy of nations and the world. Moreover, teachers once again assume their opening role by showing a management of competency strategies, with 70% of the answers in the range of acceptability, with a well-defined prognosis approach, but above all, by emphasizing the aspects of product, and the mind of the client and competency—issues which currently have repercussions in negotiations and the conducting of business transactions. In the remaining 30%, there is still observed traditional economic thinking, in which the concepts of advertising and personnel training, considered today to be issues of little significance in the economic impact of companies (Picazo and Martinez, 1999).

Regarding current issues which teachers address in their classes, 16% of the students were in favor of fiscal reform, and 14% were in favor of the issue of globalization of the economy, and of companies in competition. In contrast, 14% of the teachers said that the aspect of information and communication systems and the issues of globalization of the economy and businesses in competition (13%) are those they address with most frequently. Under the hypothesis, the CPA and BBA should bear in mind the current status and future prospects of the new economy and the dynamism of nations, but should also address the demands of the micro context, in this case the organization or company. Responses considered acceptable were economic globalization, free trade, fiscal reforms, information and communication systems, and human capital.

There was little correlation between the responses of teachers and students, since, while the first mentioned that they handled certain information in class, the latter mentioned different points. Students prioritized their responses in two prospective aspects of great importance: fiscal reform and globalization of the economy (40% of the acceptable answers), while teachers were identified with 35% of these responses, mentioning the aspects of globalization, and information and communication systems.

Of the students, 23% rated teamwork as the main element that will identify companies in the future; 19%, the vision factor; 16%, the aspect of capital/innovation; and 15% the factor of advancement. There was a tendency to agree with the teachers’ opinions, with 20% also identifying teamwork with companies of the future, and 18% pointing to aspects of vision and anticipation. The answers considered acceptable in this course were looking ahead, intangible assets, teamwork, capital/innovation, vision.

We observed that the students outdid the teachers, by identifying 85% of the answers as acceptable. Of the rest, 15% considered traditional aspects of the organizations. On the other hand, the teachers got 65% of the acceptable answers right, as opposed to 35% having a traditional or obsolete focus.

In attempting to visualize the perspectives the students and teachers have on industries that will be basic in the generation of wealth and competitiveness, the former answered with 25% for telecommunications; 21%, robotics/machine/tool, 17% microelectronics. As for the teachers, they too—23% of them—mentioned telecommunications; 19%, robotics/machine/tool; and 18%, microelectronics. The responses considered acceptable in this course were microelectronics, robotics/machine tools, telecommunications and biotechnology.

In a resounding manner, both teachers and students mentioned the four correct answers, concerning the technological developments related with the information economy and the knowledge that have given birth to new businesses and that are replacing the characteristics of the industrial economy based on oil, steel and automobiles, etc., according to Martinez and Picazo (1999).

4.3. Social and labor/ professional relevance

On the subject of using specialized software, both students and teachers say they have no access to it. However, teachers promote the use of information and communication technologies as an essential integrating tool for the training and development of the BBA and CPA degree programs’ future graduate.

As to the future employment of those enrolled in the BBA and CPA , 63% of the students believe there is sufficient employment for graduates of both degree programs, and 63.5% stated that their current employment development is related to the degree they are studying.

Opinions about the way students look at the future of their profession showed a wide diversity of results, but an equal percentage (32% each) regarding concepts: shared with another profession, and broad and inclusive.

With regard to the requirement for performing social service, 56% of the students did not consider it necessary. Among the most frequent reasons they gave is the fact that they already have practice experience (31%), and they lack time (8.1%).

Of the 39.3% of the students who felt that social service is indeed necessary, 31% believe that it serves to link theory with practice, and its connection to the development of their work. Only 4.2% of students surveyed believe that social service is a civil responsibility, and a way to repay society through community service.

4.4. Educational and didactic focus

Both teachers and students lack knowledge about the work competency model; 75.2% of the students said they were not aware that the program is based on the pattern of competencies, and only 25% of the teachers and 18.1% of the students clearly identified the characteristics of this schema (attributes, knowledge, skills and abilities). Furthermore, no diagnostic test is applied to students to detect their level of competency at the time of admission.

Consistent with the above, the answers to why these people decided to study in the BA Get Ahead program were diverse. The following reasons are conspicuous: ease of entry (17.3%); in their present job a college degree is required (11.3%); time to combine study and work (6.7%); the cost of registration and tuition (6.0% ); the program had convincing promotion (6.0%). No answers were given in the section entitled competency-based curriculum.

Concerning the teacher’s knowledge about individuality in the learning process, most of the students surveyed (50%) answered that this was taken into account only at times, while a minimum percentage (10%) said their learning skills were never recognized. On the other hand, we found that 30% of the time the teacher uses the experiences of their students for learning.

From these results it is clear that teachers rely more on methods centered on teaching, without taking into account the skills and background knowledge which the students can contribute, based on their professional practice, to promote meaningful learning.

Of the teachers, 35% said they shared their work experiences with students, and a low percentage (2.5%) said they never do. From these results it can be inferred that less than half the teachers use their own experiences in the work area to promote their students’ learning.

Of the students, 55% said they use the computer, the Internet and the management of another language, as skills in developing their studies.

The values promoted in the Get Ahead program coincide with the institutional mission established in official documents. Among the values expressed by students and teachers, conspicuous are honesty, responsibility and integrity—the same ones society requires for better living.

Less than half (32.9%) the teachers mentioned the use of a problem-solving method, while 32.7% of students indicated that most teachers use analogies as a way to induce learning.

As for the means of evaluation most familiar to teachers, and the time setting in which evaluations are applied, both parties (students and teachers), agree that the written examination is the most widely used, and that it is effected continuously during the development of the course. In addition, most teachers say they apply a diagnostic test at the beginning of the semester; this confirms the UNO Get Ahead teachers’ preference for the traditional models of evaluation when assessing their students’ knowledge.

On the subject of teaching techniques used by the instructor in class, 26.8% of those surveyed said the most useful were solving problems in real situations, and group discussion. This can be explained by taking into account the characteristics of the CPA and BBA degree programs, since using their knowledge in real situations allows students to see the problems they face in their work lives.

Finally, teachers were questioned about the last time they had received training in learning strategies; 59.1% of the teachers surveyed said they had taken courses in learning strategies during the past year. Only 31.8% answered in the negative. Remarkably, although more than half the respondents indicate that they have been trained in the use of learning strategies, this is not reflected in the current methods they use to teach their classes. Even now the autocratic prevails as the only method, apart from the few tools employed to validate the students' knowledge. This likewise relies solely on the evaluation of repetition and memorization of data, impeding the development of thought processes. No real consistency is shown between the proposed educational model and that practiced by students and teachers.

5. Conclusions

It was confirmed that the Get Ahead program complies in practice with the purpose for which it was created, i.e., addressing the need for higher education for working adults, since the vast majority of its students are economically active, and two-thirds work in activities related to what they study. However, in the study of curriculum practice, it was also shown that the minimum age requirement of 25 years is sometimes disregarded. That age is considered necessary for the Get Ahead program because it is when the student can enter the work market, and may even be running her own company—which facilitates the validation of work competencies.

Limitations concerning upgrading were found in regard to the prognosis for the current economy, specifically on how to generate wealth and issues that will be part of the new macro context radically altering the traditional patterns of supply, production, distribution and how to do business in general. In reviewing the percentages of the answers, we found that most students considered to be of little relevance aspects not located in the ideal scenario for the future and current economy—which could be considered to have originated in a traditionalist economic view. The teachers showed a wider perspective on the topics, indicating that they do have this knowledge; however, limitations were found in their teaching.

The fact that no specialized software was used in the teaching-learning activities is a limitation for the current and future training of Get Ahead graduates, and is a factor that detracts from the social relevance of this educational offer.

The way Get Ahead students see their profession in the future—shared with other professions, broad and inclusive—is consistent with the trends that prognosis specialists have identified as characteristics of professionals in the future: multidisciplinarity, having an ability to adjust and adapt to changes, having a mastery of several industrial and cultural fields, and so on.

Teachers’ and students’ lack of knowledge about the work competencies model that supports the formal curriculum of the Get Ahead program, shows a separation or distancing between what is planned and what is practiced, and constitutes the principal shortcoming found in this study. It is an obstacle to achieving a sound curriculum development.

The lack of application of diagnostic tests to detect the level of competencies at the beginning of the studies is a major flaw that makes the practice of a real competency-based curriculum difficult; when teachers do not know the student's level when he enters, they are not able to keep track in terms of learning experiences in the educational program.

The predominance of traditional teaching methods, lack of connection between students’ experience and their work competencies, as well as ignorance on the subject of the competency-based educational model, allows us to conclude that the real curriculum of the Get Ahead program is not practiced in full accordance with the model planned. By putting an end to these deficiencies, the program in question could become a robust alternative in the northwestern region of Mexico, a pioneer in higher education for adults, based on a model of work competencies.

References

Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior. (1998). Esquema básico para estudios de egresados. Mexico: Author.

Casarini, M. (1999). Teoría and diseño curricular. Mexico: Trillas.

Consejo de Normalización y Certificación de Competencia Laboral (1998). Competencia laboral. El enfoque del análisis funcional. Retrieved March 7, 2002, from: http://www.ilo.org/public/spanish/region/ampro/cinterfor/temas/

complab/banco/id_nor/conocer/index.htm

Ducci, M. Á. (1997). El enfoque de competencia laboral en la perspectiva internacional. In Organización Internacional del Trabajo, Formación basada en competencia laboral (pp.15-26). Montevideo: Organización Internacional del Trabajo-Cinterfor-Conocer.

Estévez, E. H. & Fimbres, P. (1998). Cómo diseñar y reestructurar un plan de estudios. Guía metodológica. Hermosillo: Universidad de Sonora, Dirección de Desarrollo Académico.

Estévez, E. H., Plancarte, I., Rovira, G., Carreón, E., Guerra, S., Yeomans, L., & López, I. (2001). La práctica de un currículo desde la perspectiva de estudiantes y profesores. Investigaciones Educativas en Sonora, 3, 189-198.

Hidalgo, A. and López Vara, A. I. (n.d.). Campus virtual internacionalización de la formación. Retrieved March 17, 2002, from: http://cvc.cervantes.es/obref/formacion_virtual/campus_virtual/hidalgo.htm

Ibarra, A. (1997). México: sistema de normalización y certificación de competencia laboral. In Organización Internacional del Trabajo, Formación basada en competencia laboral (pp. 79-84). Montevideo: Organización Internacional del Trabajo-Cinterfor-Conocer.

López Galindo, L. (2000). Los estados financieros and la toma de decisiones. Proyecciones, 2 (8). Retrieved March 7, 2002, from:

http://www.cem.itesm.mx/dacs/publicaciones/proy/n8/exaula/llopez.html

Monero, C. (1998). Estrategias de enseñanza and aprendizaje. Mexico: Secretaría de Educación Pública.

Organización Internacional del Trabajo. (1997). Formación basada en competencia laboral. Montevideo: Organización Internacional del Trabajo-Cinterfor-Conocer.

Picazo, L. R. & Martinez Villegas, F. (1999). Las nuevas dimensiones del contador público, rumbo al Siglo XXI (en su desempeño professional, identidad y forma de pensar). Mexico: McGraw Hill.

Stenhouse, L. (1991). Investigación y desarrollo del currículo. Madrid: Morata.

Universidad del Noroeste. (1997). Proyecto de creación de las carreras de Contador Público y Licenciado en Administración de Empresas, bajo la modalidad de educación basada en normas de competencia. Hermosillo: Universidad del Noroeste, Dirección Académica, Coordinación de Proyectos Especiales.

Universidad de Guadalajara. (1999). Diseño curricular por competencias. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, Coordinación General Académica, Unidad de Innovación Curricular.

Vinagrán, T. (2000). El contador público en el nuevo milenio. Proyecciones, 2 (8). Retrieved March 17, 2002, from:

http://www.cem.itesm.mx/dacs/publicaciones/proy/n8/exaula/tvinagran.html

Translator: Lessie Evona York-Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

Please cite the source as:

Estévez, E. H., Acedo, L. D., Bojórquez, G., Corona, B., García, C., Guerrero, M. A., et al. (2003).The curricular practice of a work-competency model for adult higher education. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 5 (1). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.ens.uabc.mx/vol3no1/contents-estevez.html