Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 9, No. 1, 2007

The Educational Community and the School:

A Case Study, by Means of the Combination

of Different Techniques, of a Public

Secondary School in Argentina

Mirta Giacobbe

(1)

giacobbe@irice.gov.ar

Nora Moscoloni

(2)

moscoloni@irice.gov.ar

Nora Bolis

(1)

bolis@irice.gov.ar

Javiera Díaz

(1)

diaz@irice.gov.ar

1

Instituto Rosario de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Educación

Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas

Universidad Nacional de Rosario

Blv. 27 de Febrero 210 bis

2000, Rosario, Argentina

2

Instituto Rosario de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Educación

Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas

Programa Interdisciplinario de Análisis de Datos

Universidad Nacional de Rosario

Maipú 1065, of. 203

2000, Rosario, Argentina

(Received: September 12, 2006;

accepted for publishing: February 20, 2007)

Abstract

Research projects in which qualitative and quantitative techniques are combined entail the difficulty of an integral interpretation of the results, due to the particular characteristics of these two approaches. In this article the methodology applied in a case study carried out in an educational institution is described. The study was especially directed towards discovering the particular elements of teacher training which can hinder a constructive teaching practice, ascertaining the role that each of the educational actors performs in the construction of their school, and identifying the characteristics of the educational community that shape the performance of the institution. The study involved the collection, processing and analysis of materials relating to students, teachers, parents and administrators. Each group is addressed methodologically in a different way. Low levels of school performance and difficulties in the integration of the educational community were found. Some proposals for rectifying them are presented here.

Key words: In-service teacher training, parent-teacher relationship, parental participation, educational environment, secondary education, research methodology.

Introduction

One of the controversial aspects of the educational reform which took place in Argentina starting in 1993 concerns the role of the teacher in regard to the complex web of relationships between the school and the community and the new roles which society demands of them. The second problem, as specific as the first, is the need to constitute the educational community of each institution, with the integration of all of the actors.

With these issues as a starting point we have worked on training teachers using a model called Investigative Didactics (Giacobbe, 1999; Giacobbe and Moscoloni, 1997, 1999; Giacobbe, 2005; Stenhouse, 1987), which has a constructivist approach as its foundation.

We propose that this framework integrates diverse theoretical views which, in practice, converge: Piaget—as conveyed to the classroom by Aebli (1985, 1988, 1991)—and Vygotsky (1979), as well as numerous Spanish authors (Carretero, 1998; Carretero and Pozo, 1989; Pozo, 1994; Coll, 1990, Coll and Solé, 1991; Gimeno Sacristán and Pérez Gómez,1988, 1993); to which we add Morin’s view of the paradigm of complexity (1994).

With this perspective, the research group organized many teacher training courses, in which the participants achieved the proposed objectives to a greater or lesser degree. However, the most difficult problem to solve is how to break out of the prevailing situation in the teachers’ schools with respect to the entrenched model of teaching-learning, which is still in use at many educational institutions.

Many empirical studies conducted with the course material used in the improvement classes showed that obstacles appear when attempts are made to change established daily classroom practices.

This situation led to the idea that the courses should be given in individual schools, addressed to their own educational community and focused on their own particular topics and problems, which are arrived at by consensus. In this way, the focus of the study was moved into the school.

Starting from a theoretical perspective that considers the school as a flexible institution which is the product of its historical-cultural conditions, as well as of specific corporative characteristics (Fernández, 1997), questions were brought up about the web of relationships among the different members of the educational community: What role does each of the educational actors play in the building of their school? What are the characteristics of the community that make up the profile of the school?

These questions led to our devising an exploratory case study which would provide more detailed information. The objectives were the following:

- To identify the particular elements of teacher training which could hinder constructive teaching practice.

- To ascertain the role which each of the educational actors plays in the building of their school.

- To identify the characteristics of the educational community that influence the performance of the school.

I. Methodology

The case study is a qualitative study which is appropriate for small-scale research—in relation to time, space and resources—, but which is of enormous complexity and composed of multiple variables (Stake, 1998).

This study posed a methodological challenge because it involved combining materials of different types and origins in order to process, analyze and interpret them in an integral manner. Thus we arrived at an instance of methodological triangulation (Vasilachis de Gialdino, 1992; Vera, 2005).

For the case study we chose an institution classified as one of the so-called former technical schools.1 First, we analyzed the existing documentation that broadly reflected its most representative characteristics. From this information, data collection instruments were designed, aimed at the three groups of actors in this educational community:

- Students: The third cycle of Basic General Education (EGB)2, was the focus of the study (the school does not have 7th grade). The cohort of 89 students enrolled in the 8th grade of EGB in 2000 was followed in order to evaluate their performance in terms of the grades obtained by subject, the number of students who repeated grades and the number of dropouts corresponding to that cohort for the period 2000-2003.

- Teachers: Out of a total of 59 teachers at the institution, 30 voluntarily agreed to fill out a survey. The survey questions, both open and closed-ended, were designed to learn the teachers’ opinions on such issues as: the social role of the school, its relationship with the community and the level of commitment to the institution. Also considered as variables were the teachers’ total number of classroom hours, total number of hours spent in the institution, their year of graduation, the type of degree earned and the subject taught.

- Parents: We carried out a semi-structured interview with the parents using both open-ended as well as more guided questions. The study population consisted of 29 parents of students in the 9th grade, a sample which represents 35% of the total. We selected 9th grade on the grounds that the parents would be more familiar with the characteristics of the school than the 8th grade parents, bearing in mind that the object of the interview was to ascertain the parents’ expectations in regard to their children’s education, as well as their views and proposals in relation to their involvement in the school. The parents were invited to participate by various means: at a meeting organized by the school to hand out report cards, through notes sent home with the students and via direct telephone calls.

II. Results

We first present the results of the contextual characterization of the educational institution; then the results of the analysis of the student cohort and the analysis of the survey that was applied to the teachers, both of which are quantitative. Lastly, we present the results of the qualitative examination of the semi-structured interviews with the parents.

2.1 General characteristics of the institution

The school has a specific orientation3 which is different from the rest of the technical education system. Its 374 students (figure for the year 2000) come from different parts of the city as well as from nearby towns, in spite of the fact that the school is located in an area of difficult access, due to the lack of public transportation. It has a staff of 59 teachers (16% full-time and 84% part-time), of whom 44% have a qualifying degree.

In the analysis carried out by the Institutional Educational Project (PEI)4—which was prepared in due course by the institution—the following weaknesses were identified by the teachers:

- In regard to curricular teaching issues: learning problems; lack of updated content and dissociation with the students’ interests; classes that are not motivating or participative; and, finally, a low level of commitment to the institution on the part of the teachers.

- Institutional management: paucity of teacher teams that function in cooperation; lack of institutional evaluation criteria, validated by the teaching staff; absence of activities that involve all the educational community actors; insufficient commitment on the part of the parents.

In view of these drawbacks, the teachers responded in the same PEI with three proposals for projects aimed at transforming these weaknesses into strengths. This then gave rise to the question about the teachers’ current opinion regarding the accomplishment of and participation in these projects.

2.2 Analysis of student data bases

2.2.1 Age

We developed age distribution tables for the students and calculated the percentage of overage students. This was slightly higher in 8th grade (52%) than in 9th (48%), although in the 9th grade the range of ages extended higher.

2.2.2 Cohort

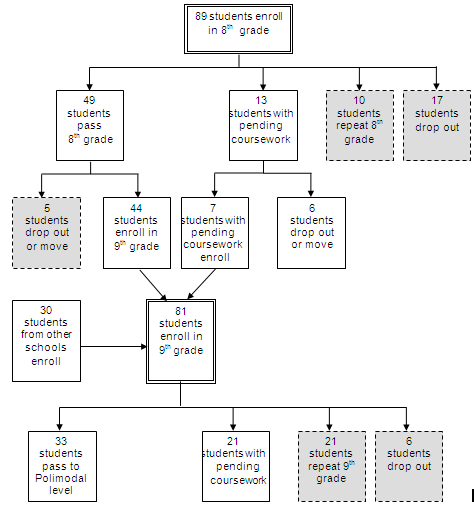

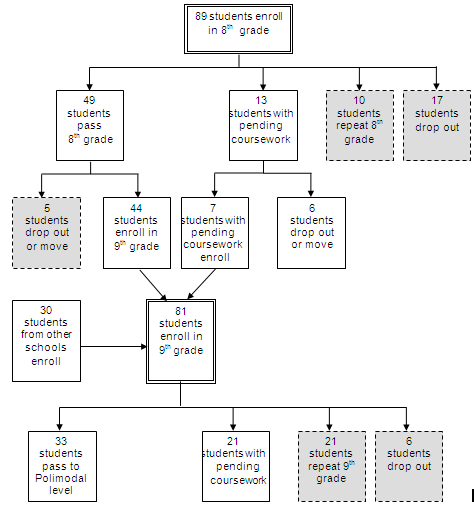

Of the students who enrolled in 8th grade, 49 (55%) passed directly to 9th grade and 14% had pending coursework.5 There is no information in the data base for an additional 11% who repeated 8th grade.

Of those who passed directly from 8th to 9th grade, 41% entered the Polimodal level; 16% eventually had to repeat 9th grade; 26% had pending coursework after 9th grade; 6% flunked out (or possibly dropped out) during 9th grade and 10% left during the 9th grade (either because of dropping out or in order to move to another educational institution). In other words, these last two groups give us a possible school dropout level of 16%.

Of this cohort, 76% of those who passed 8th grade didn’t graduate to the Polimodal level; only one student with pending coursework eventually passed 8th grade.

Of those who enrolled in 9th grade (a total of 81 students, of whom 30 were new enrollees), 41% were passed to Polimodal level; 26% repeated 9th grade; 26% had pending coursework; and 7% dropped out.

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the cohort. While the number of students in the 9th grade is almost the same as those enrolled in 8th, it is not the same population. Only 24% of the initial 89 students passed to the Polimodal level.

Figure 1. Cohort of students enrolled in the 8th grade

2.2.3 Grades

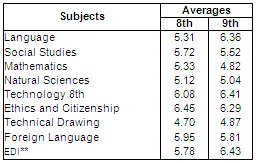

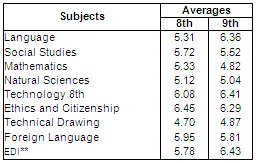

Grades are registered each trimester, by subject and grade level. The average grades by subject and grade level were then calculated and appear in Table I.

Table I. Average grades in 8th and 9th by subject

The above data were complemented by an analysis of the subjects with the highest percentage of failed students. It was noted that the subjects which presented the greatest degree of difficulty for the 8th grade students were Technical Drawing, Natural Sciences and Language.

In 9th grade the subjects which caused difficulties for the students were Mathematics, Technical Drawing, Natural Sciences and Social Studies. These figures correspond with the grade averages of the students who repeat school years.

2.3 Analysis of the surveys applied to teachers

Given the profile of the school, we can consider that the sample fulfilled the expectations, since it did not overly represent teachers with technical specialties.

There is a great variation in the time commitment of teachers, both in relation to classroom hours as well as the total time spent in the institution. However, the mean values indicate that the teachers’ time commitment is high: over 60% have more than 24 classroom hours in the institution per week.

As regards the teachers’ academic degrees, all respondents said they have a tertiary level degree.6 Judging by the year of graduation and the number of years spent teaching, 43% are estimated to be between 44 and 54 years old. The rest are equally distributed above and below this age range.

2.3.1 Viewpoints on the social role of the school

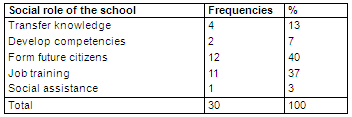

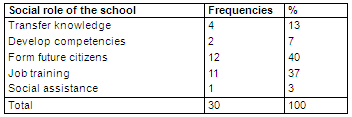

The majority of teachers agreed that the social function which the school should fulfill is to contribute to the formation of citizens and to train them for the job market, as can be seen in Table II.

Table II. Categories of responses on the social role of the school,

frequencies and percentages

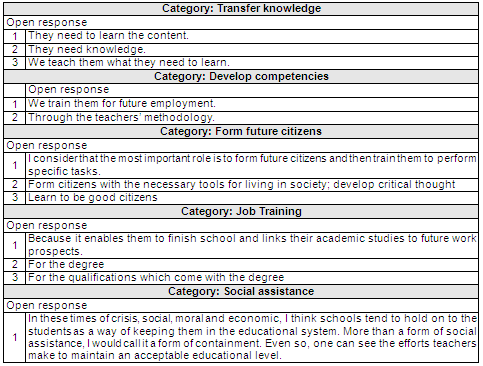

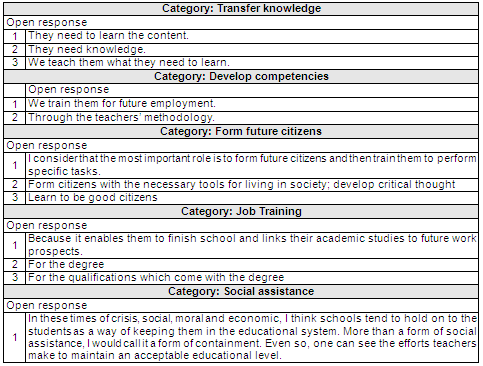

We were interested in knowing the reasons why the teachers selected a particular option as representing their viewpoint about the social role of the school. We therefore included an open response question, “Why do you consider this to be the social role of the school?”

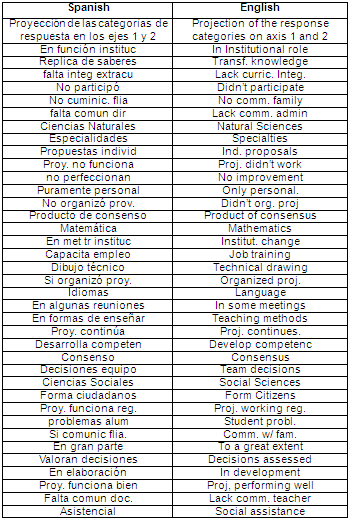

Table III displays the most typical answers to this question. Textual data were processed through the SPAD v.4.52 program that presents the responses in the order that is most characteristic for each category of response (Lebart and Salem, 1994). In this case the responses were classified according to the category that was selected as the social role of the school.

Table III. Explanatory open responses on the categories for the social role of the school

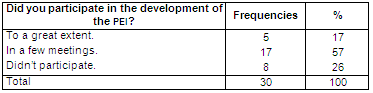

2.3.2 Participatory Dimension

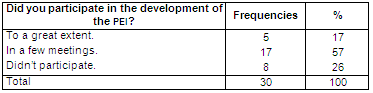

In order to determine the teachers’ degree of participation in the institution, a series of items related to the possible modes of participating—whether through the development of the PEI, or in other ways—were included. Tables IV and V present these responses.

Table IV. Categories of participation in the development of the PEI;

frequencies and percentages

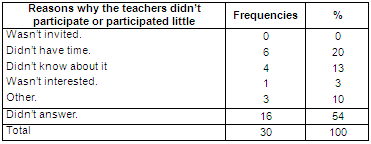

As can be observed, the number of teachers that actively participated in the activities of the institution is limited.

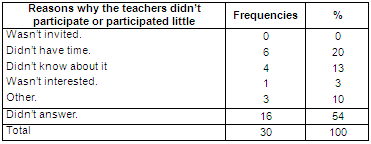

Table V. Categories of reasons for low participation in the development of the

PEI; frequencies and percentages

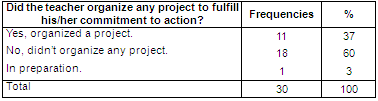

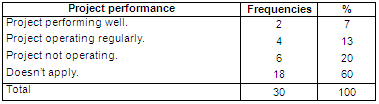

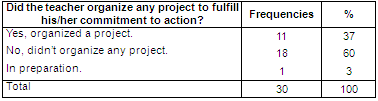

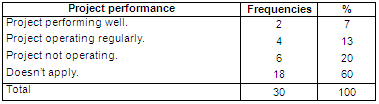

Another indicator of the level of commitment of the teachers in the institution is the organization of projects that were actually undertaken and which operate on a regular basis. Tables VI and VII indicate that less than half of the teachers answered affirmatively in relation to such projects and of these, only a small number are currently working well.

Table VI. Organizational categories of action projects; frequencies and percentages

Table VII. Categories on the performance of projects; frequencies and percentages

Teachers were also asked to make suggestions about possible changes in view of the existing shortcomings. Many of them proposed “changes in the way specific content is taught and learned.” However, over 43% suggested changes in relation to institutional issues. When asked about the individual proposals which teachers proffer, in very few cases did they report that decisions are made as a team; however, proposals are assessed and there is a degree of consensus.

2.3.3 Teacher improvement dimension

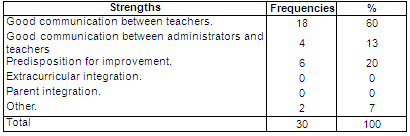

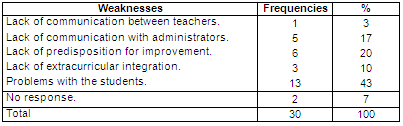

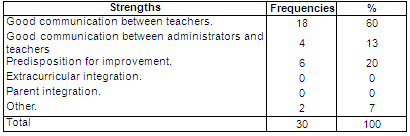

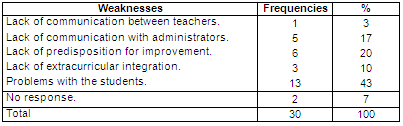

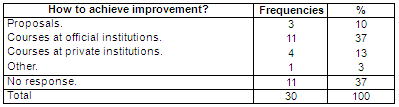

Tables VIII, IX and X refer to questions about what the teachers consider to be the most important strengths and weaknesses of the institution. It is interesting to note that they rate communication between teachers highly; their predisposition for improvement, in spite of the obstacles, is also highly rated. However, responses to questions about the courses taken do not reflect a concern for updating their teaching practices, but rather, focused mostly on disciplinary content.

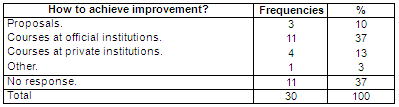

Suggestions about how to achieve improvement tend toward courses in official institutions, possibly due to their lower cost and greater possibilities for accreditation.

Table VIII. Categories related to institutional strengths; frequencies and percentages

Table IX. Categories related to institutional weaknesses; frequencies and percentages

Table X. Categories on proposals for improvement; frequencies and percentages

2.3.4 School-family communication dimension

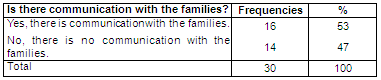

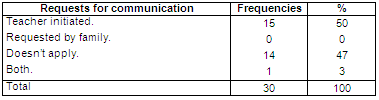

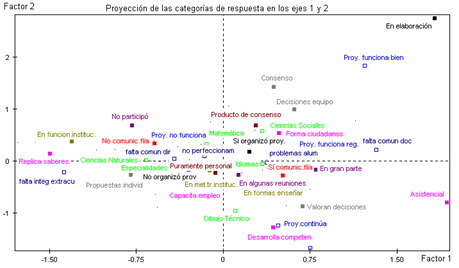

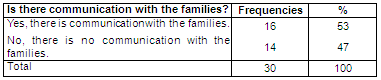

This dimension was addressed through both open and closed-ended questions. The results are presented in Table XI and Table XII.

Table XI. Categories related to communication with the family;

frequencies and percentages

As can be seen, only 53% of the teachers stated that there was some type of communication with the families of their students; of these, all replied that said communication was established after a call from the teacher himself.

Table XII. Categories related to requests for communication;

frequencies and percentages

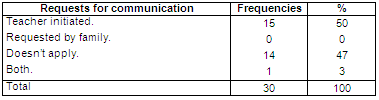

The open responses that are presented in Table XIII indicate the principal reasons why these teachers sought to communicate with the families.

Table XIII. The most characteristic open responses about the reasons for communicating with parents, by subject

With the exception of a few isolated cases, it is apparent that the majority of the teachers—regardless of the subject being taught—establish communication with the families because of behavioral problems.

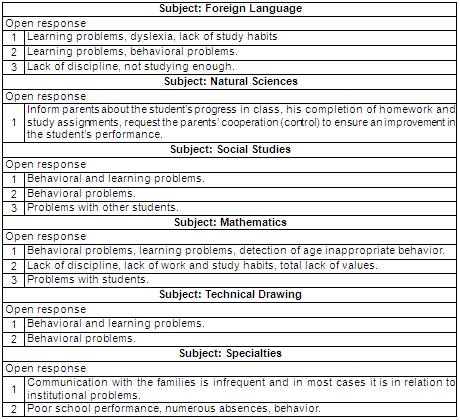

2.3.4 School-community dimension

The survey addresses this issue through an open-ended question regarding the teachers’ opinion of the community from which their students come. They were asked to broadly characterize the families (the different socioeconomic levels, neighborhoods, etc.)

The pessimistic view that the teachers have of the community is noteworthy when compared with the results of the in-depth interviews with the parents of the students. This is repeated both in the case of the teachers who state that they maintain communications with the families as well as those who do not.

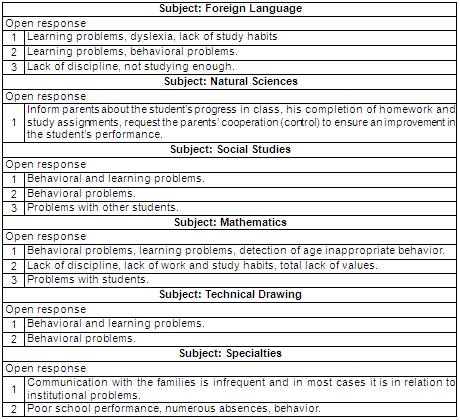

2.3.5 Characteristics of the students’ families according to the teacher’s communication with the families

Table XIV shows the open responses crossed with the closed response in reference to the question of whether or not there is a relationship with the families.

Table XIV. Open responses about motives for communication, or lack thereof, with families

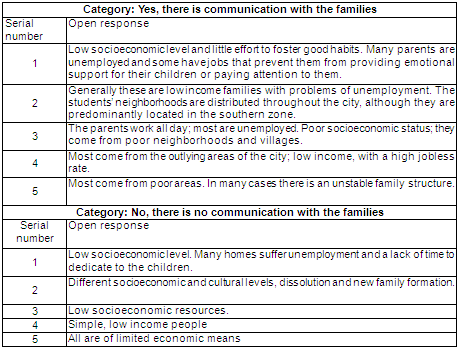

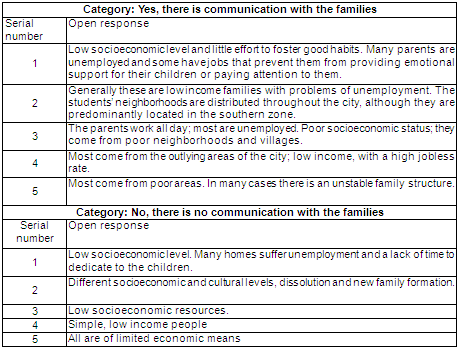

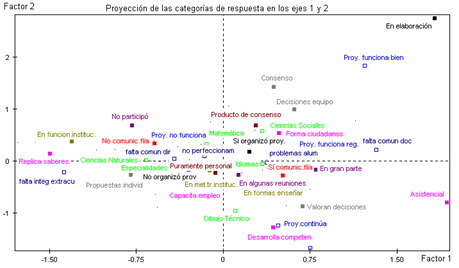

2.3.6 Correspondence analysis

In order to have an overall vision of the teachers’ response profiles we performed a multiple correspondence analysis (Lebart, Morineau and Piron, 2000), of which the factorial design is presented in Figure 2. This analysis allows us to relate the response categories that are spatially clustered (Moscoloni, 2005).

Figure 2. Factorial design of the multiple correspondence analyses

The response categories that we could characterize as showing a low level of commitment to the institution are found on the left side of the figure. These represent teachers who stated that the role of the school with which they agree is to transfer knowledge; they did not participate in the development of the PEI; they did not organize any projects, or, if they did, the projects did not work; they have no communication with the students’ families; they indicate that the institutional weaknesses are lack of extracurricular integration and the lack of communication between administrators and teachers; they would propose changes in the institutional operation; they state that innovative ideas are presented in a personal capacity.

The response categories that could be called positive are found in the upper right section of the figure. These represent the teachers who have organized projects that work well; innovative ideas are debated until a consensus is reached; they agree that the role of the school is to form future citizens and arrived at this view through consensus; they identify the institutional weakness as the lack of communication between teachers; they communicate with the families of the students and have participated to a great extent in the development of the PEI. These teachers generally belong to the Social Sciences.

In the lower right section of the figure we find another type of answer which could also be considered positive, but which differs from the previous responses in that it indicates that decisions are made as a team; these teachers maintain that the role of the school is to develop competencies; they propose changes in the mode of teaching.

2.4 Analysis of the parent interviews

The sample is composed of 28 parents of 9th grade students and represents 35% of the total parents of students in that grade.

We chose to focus on the parents of 9th grade students for the interviews because it was necessary that they have prior experience in meeting and communicating with the institution’s teachers and administrators in order to evaluate the exchanges, reflect on them and suggest ideas or proposals. Twenty-four mothers (85%) took part in the interviews, as well as 2 fathers and 2 couples.

This school presents a particular difficulty due to its isolation and the lack of public transportation which would facilitate the arrival of the students and their parents. In the selected sample 71% of the families live more than 20 blocks away, including 11% of the students who live in other towns. As the parent interviews took place on the school premises, this situation represented a significant obstacle in their accomplishment.

For the questions which are analyzed below, the parents were directly queried about their customary communication with the teachers and administrators and their mode of approaching the institution. They were also asked about their interest in participating in possible activities to be held at the school, whether connected to their children’s learning or not.

When asked whether, given their children’s age, they considered it important to be in contact with the school, the parents differentiated between the relationships they had with teachers at the primary level and those that are established within a secondary level school. Above all, they recognized that their children, as adolescents, require a greater degree of independence. This recognition results in certain limits to the parents’ possible contact with the school.

The responses are divided into two large groups, according to the parents’ position regarding their children’s schooling. In one group we have those parents, mostly mothers, who feel that they need to be present at the school on a regular basis, even if their child does not agree. In the other group we have those parents who feel that, while they should monitor their children’s schooling, they should also respect the school as being part of their child’s own “space”. A minimum set of parents felt they should not get involved with their son or daughter’s schooling.

As parents are well aware, adolescents demand their own space, which was reflected in the interviews. For example, practically none of the students liked to have their parents take them to school or show up to talk with one of the teachers.

As far as whether they visit the school of their own initiative or when they are summoned for one reason or another, most of the parents—even those who felt the need for their assiduous presence in their children’s education—waited to be called by the school.

The responses are divided into three groups:

- Parents who approach the school of their own initiative (21%).

- Parents who approach the school only if summoned (58%).

- Parents who approach the school if they are summoned and sometimes of their own initiative (21%).

When the parents approach the school of their own initiative, it is usually due to the child’s difficulty with a subject (14%), problems related to the child’s integration in the school group (7%), to seek information about their child’s academic performance (14%), and, in rare cases only, to make suggestions for the improvement of the school (7%).

All the parents were invited to the parent meetings and to the meetings where report cards are given out.

In some cases there were other reasons for summoning the parents: behavioral problems (25%), problems with academic subjects (14%) and other types of institutional activities, such as meetings of the cooperative7 (14%). But 47% of the parents were never summoned by the school for any reason other than to pick up their child’s report card.

During the interviews, the parents were encouraged to use their imaginations and propose possible activities, even if they were activities which weren’t undertaken in the school at that time.

In general, when they were asked about their presence in the school or how they had approached the institution, the parents’ responses related to their children’s performance in different classes, and, in some cases, to their son or daughter’s social integration.

When we asked questions related to a broader participation of the parents in the school, we suggested that they think of various proposals and attempted to persuade them to voice their expectations for their children. In this way they were able to formulate the following suggestions for participation and integration:

- That the teachers conduct regular meetings with parents to inform them about their children’s progress and whether they are having any difficulties. That there be support from the school for parent-teacher communication about each student’s learning process so that parents can be acquainted with the status of each subject before the end of the trimester. Parents are aware that at this time in their children’s lives—adolescence—such communication is often thwarted, for example because the students fail to deliver notes or summons from the teachers.

- That teachers not only ask to see parents because of their children’s academic or behavioral problems, but also to inform them about teaching projects or proposals.

- That tasks for improving the school be joint projects of teachers and parents, especially those related to the school building.

- That the school organize community integration activities: conferences, recreational and sporting events, etc.

- That meetings be organized for parents to exchange ideas and experiences, employing the help of specialists to discuss issues related to the socialization of the students.

- That the cooperative deliver periodic reports to the parents about its activities.

- That science and literature competitions be held in which parents can participate with their children.

III. Discussion

The techniques used to analyze this case allowed us to examine three different frames of reference, the student’s, the teacher’s and the family’s, facilitating the construction of a contextual and holistic vision of the educational institution.

From the analysis of the cohort we can infer two striking facts: the poor performance of the students in almost all subjects and the high dropout rate.

The first is reflected not only in the poor grades and the high percentage of overage students, but also in the large number of students who fail exams and in the number who have pending coursework.

The longitudinal study allows us to answer some questions about the school’s retention rate: of 89 students enrolled in the 8th grade, only 55% passed to the next grade. In the 9th grade, enrollment is made up of those who passed 8th grade (9% with pending coursework) and another 37% who come from other schools.

The percentage of those who pass from 9th grade to the Polimodal level is even lower: 41%. Only 24% of the students who initially enrolled in 8th grade two years earlier went on to enroll in the first year of Polimodal. In other words, the student population of this school has a mobility which is the product of dropouts and incoming students from other institutions.

The survey of teachers also reveals interesting situations, such as the considerable number of classroom hours put in by the school’s teachers. This promotes integration and cooperative work. A second factor of interest is the length of time in the teaching field, between 15 and 20 years on average.

Of the teachers, 77% contend that the role of the school is to form citizens and provide job training, with which they are reiterating the objectives that correspond to the school’s orientation and level.

We found a low level of teacher commitment to the institution, as measured by the responses on their participation in the development of the PEI, implementation of action projects and communication with parents or community.

The teachers do not see the lack of extracurricular integration as a failing, but do request changes in the way teaching and learning take place.

Regarding professional improvement, some (37%) took training courses in their specialty, with a duration of more than 25 hours and generally including an evaluation. Few mentioned having taken a course on teaching methods.

The correspondence analysis allowed us to simultaneously relate all the dimensions studied in the survey.

We encountered a group of teachers with what we could call positive attitudes; they have organized projects which work well; innovative ideas are debated until a consensus is reached; they agree that the role of the school is to form future citizens and arrived at this view through consensus; they identify the institutional weakness as the lack of communication between teachers; they communicate with the families of the students and have participated to a great extent in the development of the PEI. These teachers generally belong to the Social Sciences.

Another group is characterized by responses which could also be considered positive, but these differ from the responses of the previous group in that they indicate that decisions are made as a team; these teachers maintain that the role of the school is to develop competencies; they propose changes in the mode of teaching.

A third group was considered to have low commitment to the institution. These teachers are of the opinion that the role of the school is to transfer knowledge; they did not participate in the development of the PEI; they did not organize any projects which worked; they have no communication with the students’ families; they identify as institutional weaknesses a lack of extracurricular integration and lack of communication between administrators and teachers; they would propose changes in the institutional operation; they state that innovative ideas are presented in a personal capacity.

The interviews with the parents of the students demonstrated that the policy which the school adopts regarding these same parents is decisive. The stance of a majority of the parents is to wait for the school to summon them according to the needs which teachers—and in particular, administrators—have established.

This attitude assumes that administrators and teachers are the ones who possess the authority to decide what is important or necessary for improving the conditions of the school. While the parents, at the request of the interviewers, were able to formulate proposals for increasing the parent-school contact and collaboration, they didn’t feel that they could submit these proposals directly to the school administration. The possibility of getting teachers and administrators to listen to parents’ ideas depends on the establishment of avenues of participation—or at least of communication—on the part of the institution.

We observe that communication directed to the parents on behalf of the school during the 8th grade is limited to information about the students’ performance, with periodic meetings between teachers and parents. Starting in the 9th grade, the only contact with the families occurs when the parents pick up their children’s report cards, occasions in which there is no organization involved. Individual appointments with the parents are generally limited to discussion of behavioral problems, usually leaving aside any issues related to the learning process.

The views expressed by the parents suggest that administrators and teachers do not consider parents as necessary actors in this process, although they are regarded as key in everything related to their children’s socialization. The students’ conduct and their social behavior in the school environment are one of the greatest concerns conveyed to parents by teachers and administrators. This is one of the most persistent and intractable institutional problems, one which remains unresolved.

In short, the school has to its credit a team of teachers trained in their specialties, with sufficient experience and work hours in the institution, three essential requisites for forming a good teaching staff. To this we could add the recognition that the role of the school is to provide the students with comprehensive formation and job training.

With respect to the parents, it is interesting to note that in our interview sample most showed an interest in and concern for their child’s integration in the school—both in regard to academic performance and conduct—, as well as their own relationship with the school. Some suggested other forms of participation not limited merely to their son or daughter’s schooling. In addition, parents value the school as a place that provides knowledge and training—which in many cases they themselves were unable to obtain—and the possibility of concrete and attractive job prospects.

However, all of these positive elements are not appropriately channeled and we find ourselves with an educational community that fails to integrate the different actors. This, coupled with the poor performance and high dropout rate of students, leads to the goals parents envisioned for their children not being fulfilled.

In spite of the fact that from the moment the PEI is developed there is acknowledgement of the fact that poor student performance and lack of integration of educational actors are institutional weaknesses, and action projects are designed to counteract these weaknesses, there is no evidence that such projects can be undertaken.

Still, the school administration does take into account the value that parents place on the specific orientation of the school and its job approach. The administration strives to relate the themes of the curricular content with the preparation of the students for further study or work in their fields. This approach began with the organization of internships starting from the first year of the Polimodal level.

This study has been returned to the educational institution through the preparation of a report to the teachers on the proposals for parental involvement. With this report we have attempted to improve communication between the two groups. Likewise it was suggested that workshops on integration be organized as part of a plan of activities to reassess the role of the school and to build the educational community through the integration of all of its actors.

References

Aebli, H. (1988). Doce formas básicas de enseñar. Madrid: Nancea.

Aebli, H. (1991). Factores de la enseñanza que favorecen el aprendizaje autónomo. Madrid: Narcea.

Aebli, H. (1985). Una didáctica fundada en la psicología de Jean Piaget. Madrid: Nancea.

Carretero, M. & Pozo, J. (1989). La enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales. Madrid: Visor.

Carretero, M. (1998). Proceso enseñanza y aprendizaje. Buenos Aires: Aique.

Coll, C. & Sole, I. (1991). Aprendizaje significativo y ayuda pedagógica. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 18, 12-22.

Coll, C. (1990). Aprendizaje escolar y construcción del conocimiento. Barcelona: Paidós.

Fernández, L. (1997) Instituciones educativas. Dinámicas institucionales en situaciones críticas. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Giacobbe, M. & Moscoloni, N. (1997). Aprender a aprender. Construyendo un nuevo rol docente. Rosario: Universidad Nacional de Rosario.

Giacobbe, M. & Moscoloni, N. (1999). Aprender investigando. Rosario: CERIDER.

Giacobbe, M. (1999). La formación del enseñante. Algunas reflexiones ante un curso de perfeccionamiento del profesorado en el marco de la reforma educativa argentina. Revista Cultura y Educación, 17-18, 83-91.

Giacobbe, M. (2005). La formación docente: un camino hacia la profesionalidad. Rosario, Argentina: Fundación Aprender a Saber.

Gimeno Sacristán, J. & Pérez Gómez, Á. I. (1988). La enseñanza, su teoría y su práctica. Madrid: Morata.

Gimeno Sacristán, J. & Pérez Gómez, Á. I. (1993). Comprender y transformar la enseñanza. Madrid: Morata.

Lebart, L. & Salem, A. (1994). Statistique textuelle. Paris: Dunod.

Lebart L., Morineau A., & Piron M. (2000). Statistique exploratoire multidimensionnelle. Paris: Dunod.

Morin, E. (1994). Introducción al pensamiento complejo. Buenos Aires: Gedisa.

Moscoloni, N. (2005). Las nubes de datos. Métodos para analizar la complejidad. Rosario: Universidad Nacional de Rosario.

Pozo, J. I. (1994). La solución de problemas. Buenos Aires: Santillana.

Stake, R. (1998). Investigación con estudio de casos. Madrid: Morata.

Stenhouse, L. (1987). La investigación como base de la enseñanza. Madrid: Morata.

Vasilachis de Gialdino, I. (1992). Métodos cualitativos I. Los problemas teórico-epistemológicos. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina.

Vera A. (2005). Diálogo entre lo cuantitativo y lo cualitativo en la investigación científica. El desafío de la triangulación. Ciencia & Trabajo, 7 (15), 38-40.

Vigotsky, L. (1979). El desarrollo de los procesos. Barcelona: Crítica.

Translator: Jeanne Eileen Soennichsen

1Traditionally, in Argentina, there were schools at the secondary level that were called technical schools, which trained “technicians” in, for example, Chemistry, Mechanics, Electricity, Electromechanics, Robotics, etc. These schools, after the reform of the Federal Education Act, lost their specific focus, and were included in the so-called Polimodal Level.

2The Federal Education Act, passed in 1993 and repealed in 2006, divides the compulsory primary education—called Basic General Education or EGB—in three cycles of three years each. The third cycle corresponds to 7th, 8th and 9th grades.

3We call any of the possible modalities that schools in the Polimodal level should adopt a specific orientation. [Translator’s note: The Polimodal school—“polymodal”, that is, having multiple modes—, usually encompassing 10th, 11th and 12th grades, is a system in which each institution offers one of five different orientations: Communications, Arts and Design; Natural Sciences; Economics and Business Administration; Production of Goods and Services; Social Sciences and Humanities.]

4The Institutional Educational Project or PEI, is an internal school document which is drawn up by all those involved in the educational process during the first school year of the application of the Federal Education Act, in accordance with the stipulation of the Ministry of Education. The document identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the institution as well as any action projects which are to be undertaken to remedy the latter. If the Act had continued in effect, these projects were to have been continually modified, according to the needs of each institution.

5That is, the subjects which the student fails during a given school year are then left pending for the following academic cycle.

6In Argentina, irrespective of the current legislation, there is, generally speaking, primary, secondary, tertiary and university education. The tertiary level consists of four year degree programs, which include teaching degrees.

7School cooperatives are associations which exist in many schools. They may be organized by school authorities or the students’ families to promote the participation of parents in school operation with the aim of improving the budgetary situation or other problems the school may face.

Please cite the source as:

Giacobbe, M., Moscoloni, N., Bolis, N., & Díaz, J. (2007). The educational community and the school: A case study, by means of the combination of different techniques, of a public secondary school in Argentina. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 9 (1). Retrieved month, day, year from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol9no1/contents-giacobbe.html