Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 6, No. 1, 2004

Individual and Social Assessment in a

Global Distance Education Era

Angéline Martel

amartel@teluq.uquebec.ca

Unité d’Enseignement et de Recherche Sciences

Humaines, Lettres et Communication

Télé-université du Québec

4750, Henri-Julien

Montréal, Québec, Canada H2T 3E4

Abstract

In the context of a growing globalization, encouraged, namely by distance education, we are asked to question the values that it conveys to local cultures. The evaluation procedures that we plan in our courses can thus become another mechanism of homogenization. In order to counter these disadvantages and to build distinct but interdependent local societies, I propose an analysis of evaluation as an ideological tool for the pereptuation of competition or for the construction of solidarity. This presentation is both theoretical, by painting a picture of contemporary ideologies (those of solidarity and those of competition) and practical, by showing how these ideologies function in evaluation and in the construction of knowledge. From this point of view, methodologies, curricula and evaluation are important steps to uncover competition and focus on actions and speeches of solidarity.

Key words: Assessment, distance education, solidarity.

Introduction

It gives me great pleasure to share with you all these reflections concerning the evaluation in distance education. It delights me to do it here in Guadalajara, Mexican city of international physiognomy, host city of Quebec that is in its turn a city open to the international culture to globalization, without forgetting its own local culture.

We could not find a better setting to evaluate the evaluation than in our societies, primordially given that the same evaluation of the education has its roots in our educational systems, and afterwards clearly, in distance education.

My main subject parts from the hypothesis that, in a globalization in expansion, favored in an important way by distance education, we must question ourselves about the values that we associate with the local cultures. The contents, the values and the processes in which the evaluations that we establish within our courses can also convert themselves in homogenization mechanisms. To stop these disadvantages and to build together different but solidary, plausible societies, I propose an analysis of the evaluation as an ideological vehicle of perpetuation of the competence of the solidarity.

My presentation is as much theory, painting a picture of contemporary ideologies (those of the solidarity and those of the competence) as it is practical, that shows how these ideologies function in the evaluation and in the construction of knowledge. Within this perspective, the methodology, the curricula and the evaluations are determinants and they will expose the competence at the same time as they attract the attention towards the actions and the discourses of the solidarity.

1. Historical evaluation of the evaluation: from the value and the vitality to the devaluation and the blame

What is the evaluation? Not in the superficial sense of the concept or in all its variants (formative evaluation, accumulative, subjective, by objectives, auto-evaluation, shared evaluation, negotiated, authentic, individual, collective, quantitative, qualitative, evaluation of classification, of progress, of success, etc.) but in its more profound sense for our life in global societies and our learning of knowledge within a world increasingly universal. And in the distance, as in distance formation, does there exist some change?

It is at the most profound possible level of our individual and social life that I wish to present these two questions to you all, along with a cadre of interpretation of questions, of the history of the concepts and of the societies. Therefore as an objective, we will evaluate the process, at the end of making a long journey. I propose we keep each other centered in the fundamental and avoid any mythicized discourse.

The etymology of the word evaluation permits us to return to the value of words. Evaluation and to evaluate come from ancient French avaluer (XIII century) and of value, that is to say, to be vigorous, to have value and to receive a premium. The evaluation, therefore, is an act of giving a value or to value. Within the concept in ancient French, there exists a dimension of life and of activity that is interesting for reintegrating it within our actual concept of the evaluation. In this path, to evaluate, contributes to the sense of having a monetary value or the vitality that this one produces. These are two criterions according to the material value (money) and the vital value (life) that history teaches us. But besides illustrating these positive values of the concept of the evaluation, it shows us an autonomous evaluative focus, that is to say, not as controller.

Some centuries later, the evaluation strips itself of these vital, material values to support itself on its opposite: the competence and the culpability by the error. In Who, one day, had this crazy idea to invent grades in school?, a story about the coded evaluation that is at the disposition of those who want to abuse on others, Claude Maulini portrays this story in the following way:

The procedures developed by the Jesuits and formalized in the Ratio studiorum are for the most part from the XVI century. The first “distribution of awards” took place, for example, in a college in Coimbra (Portugal) in 1558. At the end of the XVI century, the College of Geneva granted awards in silver, besides giving medals to the more meritorious students. But in what did they base these classifications? In the beginning the teacher counted the faults in the compositions and arranged the copies according to merits. In occasion he transmitted the results to the families, accompanied by brief written commentaries. The increase of actual pensioners will carry with itself the normalization of the correspondence that will become increasingly laconic (Maulini, 1996, Classements et bonnes notes, par. 2).

In three centuries, the valuation evident within the origin of the word, therefore, is transformed in a competence that is based on the practices on the devaluation and the culpability: the less possible errors. The negative judgment that the evaluation, and at the same time the competence and the culpability, establishes a dimension of individual and social control.

The practice of the competence in the devaluation is not very distant from our collective conscience. Have you been evaluated by the deduction of errors? I will always remember my first university level homework in my first history course. I received a great 16% and I was the best of the group. The professor surely took into account each small grammatical, orthographic, logical error, etc. and multiplied it by 5 points. We live, without being conscious of it, under the regime of the devaluation in relation to external norms to ourselves, historical, linguistic, logical, social, educational norms, etc.

Moreover, the dimension of the control has been transformed and refined at present by concepts just as those of the evaluation have been by objectives, or more still by that one which guides the action. For example, this is the definition within the Glossaire de la formation à distance (Glossary of distance formation), (Ministère de l'Economie, des Finances et de l'Industrie, s.f.):

Evaluation of the formation: Act of appreciating, with the help of criterions previously defined, bearing in mind the pedagogic objectives and formation of a formative action. This evaluation can be carried out at different times, for different actors (strategies, formative, company, client…). One can distinguish, for example, the evaluation from the satisfaction, or the evaluation from the content of the formative action, the evaluation of the acquisitions and the evaluation of eventual transfers in localities of work. (AFNOR), (Letter E, para. 5).

Formative evaluation: It is practiced during the course of learning and it has as its objective to teach the student in the most complete, precise way possible about the distance that separates it from the objective and on the difficulties that it can face (Letter E, para. 6).

Summary evaluation: It is practiced at the end of the period of learning and it has as its objective to verify if the objectives were reached by one student or another (Letter E, para. 7).

This contemporary dimension of control by means of the evaluation distinguishes between the formative evaluation (verification of the objectives in short term) and the summary evaluation (verification of the objectives in long term).

The history of the evaluation shows us a double movement: those of the valuation (reward of vitality) with that of the devaluation (error) in the competence for a part of that one with the initial autonomy against a control of the root. How does this double movement combine itself in actuality? It is a question that I will try to answer in the following sections of this text, given that I propose an evaluation of the ideological environment, of the educational, of those of distance education; all based on a reflexive fundamental movement.

In this text, I place myself in the heart of the evaluation as a valuation of positive, material, and vital values. These inscribe themselves in a context of individual and collective formation in the election of these values that replace an entire dimension of control that establishes itself in the evaluation just as they are frequently practiced. I announce therefore a democratization of the evaluation.

2. Contemporary evaluation of the evaluation: The desire of evaluating in daily life to direct the action

The evaluation is a great movement that we carry out as human beings in our daily and professional life. We value or devalue, according to the fundamental values, constructed socially or individually. And given that our educational values have their roots in our social practices, let us take a moment to examine ourselves in our daily life.

On what basis nowadays do our societies and our educational institutions, that is to say, do they furnish us a value, an award or vitality? And do these evaluations have anything to do with our own individual values?

As a first analysis, I walk around my house and I reflect about the evaluation and the valuation:

-

Why is it that the water of the bathroom, once used, is discarded through the drainage? I dare to evaluate the wastes that our Western societies practice. It is not wise to discard the water of the personal bath to the drainage. Why not recycle this water to cultivate vegetables in the garden?

-

Why does the water of the dishwasher have to disappear through the drainage? If this is dirty water then it is so because we add products to wash the dishes. How could we wash the dishes, pots and pans without soiling the water?

-

Why does the whole world gather up the dead leaves in the autumn and then throws them away in trash cans or puts them into sacs to elaborate fertilizer? Why not crumble them and place them in the garden? Why also waste time in elaborating this raw material for the garden?

-

The city of Montreal, like all the cities of the world, takes its water freely from nature but considers that the way of charging for it is with a measurer of water installed in all the houses to charge it to all of the residents. I would say that this is exploitation.

Because of this question of the water, on a scale of 10, I would give our western society a 1. Therefore I don't agree with the values that constitute these gestures and they allow me this evaluation. What is it that gives me the right, the responsibility and the possibility?

I continue taking a walk through Montreal and I reflect. I enter an art gallery. Beauty is personal. A good moment to reflect:

-

Why does this colored painting cost so little in comparison with this other one that made me shake with its color and its theme? Do the prices function in relation to the negative emotion that it produces in its spectators?

-

They inform me that they don't commercialize works of art of living artists. Death makes the prices of the works of art increase; is it the pains fault?

Again I don't agree with the values established through this art gallery: the pain, the gains.

These questions and many others have in common the valuation that we devote to these things: water, our efficient time, dead leaves, our capacity to question everything, etc. They are also a “wanting to evaluate the environments”, the vision that we possess on our environment. But, why can we also value this? What gives us the freedom?

Our education? In my case, Yes, I had a mother very respectful of the environment and a father that worshiped the earth and the trees. But no, it was not in school nor in the university where I learned these values.

Our societies and our scientific disciplines after a long time tended to eliminate the open act of the valuation and even more so of the valorization. We apply the scientific objective that tries to base itself in verifiable hypothesis and not in unobservable values. We talk of the “cultural relativity”, that impedes us to judge a component according to our proper nouns. We do it justifying our title. As long as, these two adversaries don't impede demythicizing the hidden values. They function as the forbidden that one not dare transgress, for fear of social or professional sanction.

The first foundation of the evaluation looks to me as the “wanting to evaluate” in both senses of the word: to accept what a value has and refusing that which annuls this value and this in contact and with the respect of the others. This movement is known under the concept of the reflection of Stephen Brookfield, identified, likewise, the intentions and the substance:

We teach how to change the world. The hope that sustains our efforts to help the students to learn is that in doing this it will help them to interact between themselves and with their surroundings with compassion, understanding and justice. But our attempts in increasing the quantity of love and justice in the world are never simple, never ambiguous. What we think to be democratic ways, respectful in treating others, can be experimented on by them in oppressive and suffocating ways. One of the more difficult things that teachers learn is that the sincerity of their intentions doesn't guarantee the purity of their practice. The political, psychological, and cultural complexities of the apprenticeship, and the ways in which power can complicate all human relations (including those between students and teachers) means that teaching can never be innocent (Brookfield, 1995, para.1).

[...]

The critical reflection is a particular aspect of the great process of the reflection. To fully understand the critical reflection, first we need to know something about the process of reflection in general. The most distinctive characteristic of the reflexive process is its attention in hunting suppositions.

The suppositions are the beliefs, that we consider as a fact, made about the world and of our place in it, that appear so evident to us, that they do not need to be established explicitly. In many ways we are our own suppositions. The suppositions give sense and purpose to who we are and what we do. In being conscious of the implicit suppositions that frame our way of thinking and acting is one of the most bewildering, intellectual challenges that we face in our lives. It is also something that we resist instinctively, for fear of what we could discover. Who wants to clarify and question suppositions with which one has lived with for a long period of time, only to discover that they make no sense? What makes this process of hunting suppositions so particularly complicated is that not all the suppositions are of the same nature? I have found it useful in distinguishing them in three big categories –paradigmatic, prescriptive and causative (Brookfield, 1995, Undestanding reflection as hunting assumptions, para. 1, 2)

Also, Brookfield (1995) inserts the teleological value of the evaluation, placing it, not like a controller of society, but like a springboard to build better the societies, conscious and collectively.

But to understand well the underlying hypothesis of our practices and contemporary thoughts, to free itself at the end of evaluating, it is also useful to know the current ideological configuration. From my viewpoint it is not enough with only wanting to evaluate. It is necessary to give clear points of reference on the underlying values, to see them better. It is Brookfield who confirms again: “The pupils can only make informed decisions on that of which they know” (1995, Hunting assumptions: Some examples, para. 10), like all other human beings.

3. Evaluation of the ideological environment: to know the option between the solidarity and the attendance

There exists, in our societies, as in all processes of teaching/learning, a turbid constant environment between the discourses/gestures/actions/plans/thoughts and theories, that in an efficient way, have a real effect in the rivals and others that have real effects in the solidarities.

On this theme, it is important to take a scientific precaution: our academic discourse and our investigation are frequently impermeable to the paradigms that function as filters, seldom identified, of our interpretations of basis as if seeing through eyeglasses “Of the color of the crystal with the one which sees” as the film producer Bergman would have said. If we take to heart in destroying these paradigmatic filters, we can withdraw from them that which we deem as unacceptable in science, the emotive effects, to use them as lenses of observation of the world and its actions.

To separate these two ideologies and its effects in a better way, let us see then how, at the beginning of the XXI century, two paradigms furnish the ethics that face the planetary failure, so much in the discourses as in the social practices. These paradigms are the ideological constellations formed by multiple variables. Or, the ideologies of the competence are nowadays principally in the majority while those of the solidarity are in the minority but in ascent.

The emergence of the ideologies of solidarity concretize the movements of identities and gives them a theorization that it is at the same time contextualized, functional and critical. These ideologies of solidarity demythicize the constant competence between communities and settlements, establishing naturalization conditions and of sustenance of the difference. On this equalitarian axis (horizontal) therefore, the ideological constellations founded on the solidarity and the complementariness 5 tend to carry out a return of the axis of power, tend to resist themselves, to see inclusive the opposite, the organisms and the parasitic, socio-political relations that favor the competitiveness. The paradigm they form is also in actuality, a product of the West for the means of intercultural communications and the interchanges between the civilizations. This paradigm of the solidarity rests itself on four epistemological foundations (at least):

-

Refutes the notion of the survival of the fittest and substitutes it for that of the responsibility of the strongest over the weakest.

-

Preconceives the complementariness with the other, as a tool for human development.

-

It stages new actors (activist individuals or intellectuals, belonging to non-governmental organizations, ethnic, linguistic communities, etc.) that refuse to the powers, to the authority and to the domination.

-

The good will rest on the individual well-being, attainable by the collective development.

This constellation of ideologies legitimizes and values the diversity, as diversity (and not as strategy), so much linguistic as cultural, racial, sexual, geographical, etc. In doing this, it recognizes the equality of the villages, of the communities, of the individuals and favors an ethos of no violence in politics and within human interactions. Diversity then is not marginal. On the contrary, the diversity composes itself of a diversity of individuals, of “inter-actors” that, who over the years have acquired an experience of minority in the sense of domination (Tellefson, 1991: 15-16). The generalization of this paradigm could be the “true progress of humanity” as much as the realization that the ecologies that function are those that have a low level of competitiveness and a high level of solidarity.

On the other hand, on a hierarchical axis (vertical, so to say), the dominant ideologies stick together around the notion, and the practices, of the competence. The globalization of interchanges and of societies permits the intensification of this flow of competitiveness while the competence ceases to be a means of converting itself in an end of itself, a form of life (Petrella, 2002). These ideologies rest on four epistemological pillars (at least):

-

Inspired by the theories of the presumption of the “law of natural selection” the survival within the physical and animal world that concludes, basing itself on Darwin,2 the survival of the fittest.3

-

The notion of freedom is perceived as an instrument for human development.

-

The idea that the gain, extension of the economic block, is a legitimate and desirable recompense of the human activity. The gain would represent the Good.

-

Money, as a universal instrument, governs the necessities of positioning.

The positioning in power relations, is then in function to the degree of obtained gains. The objective of the action is in that moment instrumental. The technique and the reason are effective means to reach the impersonal objectives.

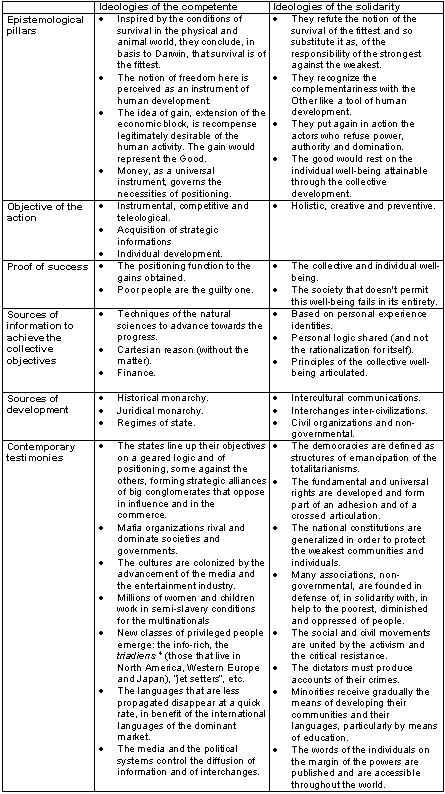

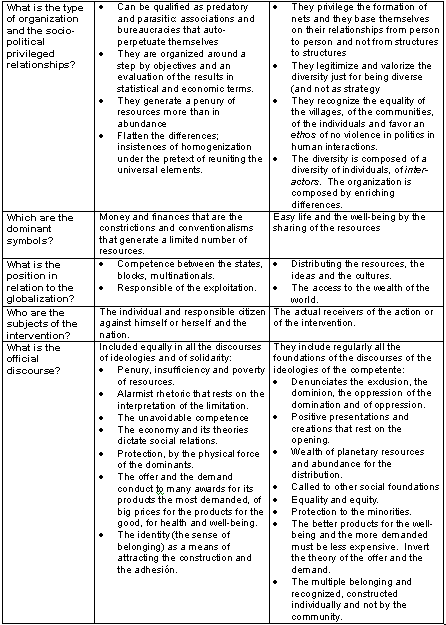

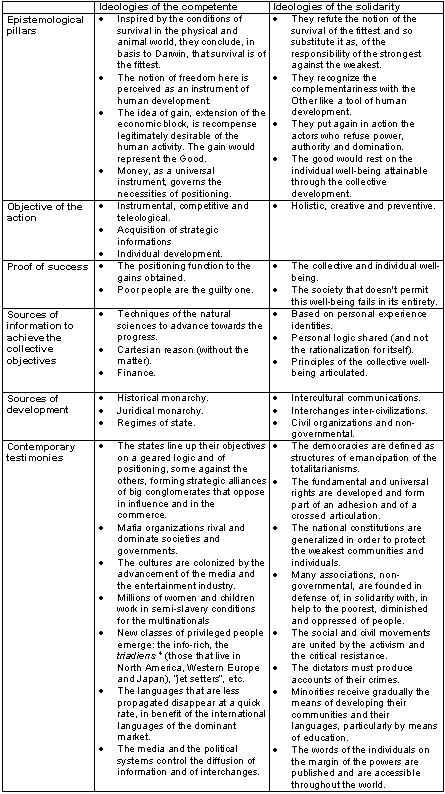

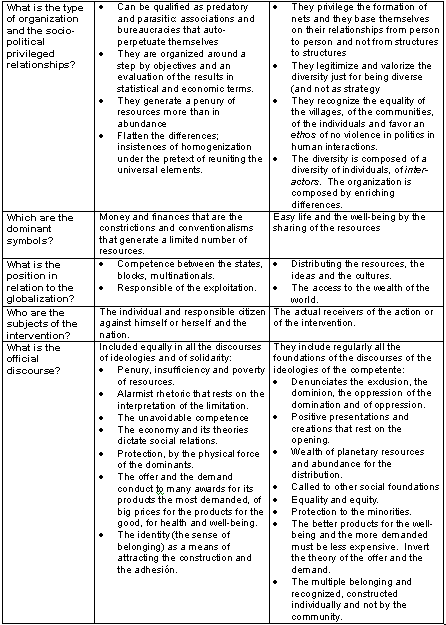

Table I schematizes these two ideological constellations in reference to its epistemological pillars, the objectives of its actions, the proofs of success, the sources of information to reach the collective objectives, the sources of development and the contemporary certifications.

Table I. Description of the big contemporary ideologies

To understand the functioning of the contemporary ideologies, let us see it in one of the movements; in those of the ecology that show how the solidarity and the competence concretize directly in the social actions.

On a first level, the notion of the ecology functions like an ideology of preservation through diverse techniques, politics and technologies: the preservation of languages, of the fauna, of the flora, of the human life, of the ozone layer, etc.

But the notion of the ecology functions also on a second level as a human ideal that guides our actions; that of life in a harmonious and respectful environment of the diverse groups that compose it. This functions then as a conceptual tool to describe the dynamics between the organisms (living, social and inanimate) within a world where presumably, the more dominant, according to Darwinian observation, survive. The objective then is to challenge this observation and to reduce this domination against harmony and protection. There is, then a paradox in appearances: the second level, a vision more idealistic for the future, guided by the first, more realistic of the past and in this way explicit and articulated or no. In this context, the ecology is the decisive factor that throws the luck in favor of the competence (Gould, 1993, p. 27).

This perspective takes into account a distinction between the movements of environmental, anthropocentric inspiration in its actions and structures and those of ecological, biocentric inspiration with a dynamic of respect and of complementariness of all time. The debate between both is more linguistic, or better said, it is linguistic because it is also ideological. The first one establishes a regime of authority over nature and material, the second democratizes life inculcating that which is material and nature (Blanke, 1996, p. 201). The urban means have been in particular, conductors of the environmentalist movement that uses nature in its horizon of reflection, and this frequently in name of development or “modern progress”. For example, about the plan of technologies, one can understand that nuclear fission, the science that emanates from the urban cultures, is not a way of working in collaboration with nature in its element in the least; it constitutes violence against nature that they denounce, among others, the philosophers and the environmental activists (Macauley, 1996). Nuclear fission has served better, rather as a tool of massive, urban elimination in armored conflicts. This technology is therefore in and of itself violence as with all the use that they have done with it.

The discourse about ecology alerts us then on the fact that not all discourse and action are necessarily of solidarity. It is important to analyze well and understand the intentions and the actions. To do this, there has to be an intellectual development with a critical thought but in the spiral movement of the solidarity.

Likewise, another train of thought, this time that of the education, comes to put into evidence the same dichotomy solidarity/competence, ecology/environment. It focuses on constructivisms that transform the instructivisms.

4. Evaluation of the environments of learning: constructivism and instructivism

This movement of solidarity, we find also now in the theories of learning called constructivists. It is what I describe in this section; all this in contrast with those we call instructivists.

We know very well the instructivists focus, so called, in light of the predominance that they present with the instruction more than with the learning. The instructivists5 refer to the educational traditional models based on the positivism. They tend to cultivate with the apprentice or student, the informations and the knowledges that are seen as “true”, that are predetermined independently of the student, of hi sor her situation and of his or her culture.

On the other hand, the constructivist movements aren’t new either. For example, Rousseau and Montaigne recognized these principles. The new, therefore, is the convergence between the humanist course in the education and the constructivists (Nunan, 1999). What also is new again is the advantage that technologies function in environments and in constructivist type projects (Sandholtz, Ringstaff & Dwyer, 1997; Hoven, 1999).

The constructivists6 refer to an educational, postmodern paradigm that postulates that the student build its own interpretations of the successes of the information (Martel, 2000a; 2000b; 1999). Knowledge is not fixed in a definitive way. The stains and the authentic projects are considered as motivating beings. The constant collaboration is an integral part of the practices. This movement continues but tends to transform the instructivisms7 that, on one hand refer to educational models based on positivism. They tend to cultivate in the student the information and the knowledge that on occasions is seen as “true” and that has been preconceived independently of the student, of his/her situation and of his/her culture.

The actual functioning of the constructivist theories with the humanisms, offers one put into critical perspective on knowledge and puts in its place the environments of collaboration and solidarity. This permits verify that the significances have been historically situated, constructed and reconstructed by language. And the course unites the knowledge and the interest of the announcer. A critical reflection stimulates, therefore, the development of these interests; this one defines the idea that there exists a simple sense of the reality. Instead of a paternalistic project of education, the constructivists relate to the emancipating tendencies and of “empowerment” in education. The dimension controls and, therefore, exposes and is diminished in great measure.

The constructivists also open an interpretive door towards interculturalism, as long as this aspect hasn’t been theorized yet. The wise ones, being the constructors of sense, follow each social context to build their own knowledges under the form of culture. The constructivists relativize the knowing in cultural knowledges. Also, the theories of learning accentuate the two dimensions: the participation with the motivational projects and work in collaboration. These constitute the two most important elements of the constructivisms: a psychological foundation based on the writings of Jean Piaget and the psycho-social dimension based on those of Lev. S. Vygotsky. Add the participation and the collaboration, that are two concepts more neutral than those of the solidarity from which they leave, taking what they are and they insert themselves in the dimension of the social affectivity.

Table II contrasts the constructivisms with the previous (traditional) tendencies that I would call the instructivisms, in reason of the predominance that they incorporate to the instruction more than the learning.

Table II. Principles of teaching/learning, of the practices, according to the

constructivists and the instructivists

When in the debate of knowing about if the two focuses are incompatible or complementary (Wasson, 1996), It appears to me fearless since our practices and Western thinking participated de facto in these two paradigms until the actual moment. And in reality of a course or of a classroom or in the Internet, the two types of practices are interconnected, no longer pure, and never lonely. Perhaps the practices include a synthesis, therefore in knowing the parameters, all like knowing the parameters of the solidarity and of competence, clear, individual and collectively options are allowed.

It is equally mandatory to verify that the constructivists, by invitation to the critical reflection, they are verified better, in measure of the apprenticeship when exposing all the forms of oppression (social, economic, linguistic, etc.) than what the instructivists do who, on the contrary, confirm, affirm and perpetuate more easily the oppressive status quo of the domination. In theory therefore, one can estimate that in their principles, the constructivists constitute a progress that we still haven’t managed to carry out in practice.

And what does domination means? Domination is a form of violence, frequently symbolic. Pierre Bourdieu furnishes a definition in his introduction to La domination masculine (1998):

sweet violence, insensitive, invisible to its own victims, that is practiced essentially by the purely symbolic paths of the communication and the knowledge --or in a more precise way, of the ignorance, of the recognition or at the limit, of the feeling (Bourdieu, 1998, para. 2).

It is a “spiritual violence, different than real violence”. This dominion is then more perverse than the “real” dominion. In all cases, we have the possibility of rebelling against it as long as it has been imposed, we can then examine, touch it. The symbolic violence appears also to be imprinted in the order of things, surpasses the justification and it is for that very reason, extremely subtle.

Domination hides also in the mundane, in the daily, in hardly anything. It is then accepted by the dominator, of course, but also by the dominated. Also, the person is dominated partly in reason of the sudden domination that finishes by contributing on the judgments of the world and itself the same characteristics of the dominator. It reflects about its condition, with its ideas that come from the same domination. The dominator has the possibility then of creating its own culture, therefore to produce ideas whose final destiny is destined to legitimize ideologically its dominion, the dominated interpret the world according to the ways of thinking that are themselves products of the domination. This “symbolic violence” imprisons inside itself, in such a way, its own mind and judgments. The domination so then becomes converted in a necessity of nature and is accepted by all, it is imprinted in the order of things.

Why do the solidarity and the intercultural solidarity exist in the globalization? It is necessary before anything else to ask the question of, how to fight against this domination? For Bourdieu it is not to make conscience effort of the existence of this domination which will in turn make it disappear, we will not subscribe to this domination laughing as if it simply did not have any kind of influence on our person. From this optics, the conscience effort of this domination is not in and of itself liberating, given that its effects are well anchored in our train of thought as it is in our corporal attitudes, as well as in the way of being, of speaking, of looking... But there is more even still. The intercultural itself demands a rejection to the domination as a train of thought and demands to adopt an attitude of rejection indirectly (blockade) towards these practices and thoughts.

Basing ourselves in this, an intercultural re-encounter would be a product of new judgments of reality and of judgments of value, begotten by other actions, the operations of the persons working in its external and internal atmospheres in equal measure.

A process of teaching/learning in what is intercultural searches then to understand the condition of the other in order to help him and help itself to improve the conditions of life, particularly on exposing the symbolic and physical violences. To give some examples, here two examples of very simple advancement that put into play the destruction of ideas received at the same time as constructing practices of solidarity. These have been robbed of its course with recognition and prepared by the distance educator in a course on the didactics of French, second foreign language and a course on the intercultural environment.8

5. Evaluation of the environment of distance education: the autonomous individual and the technology at the service of the distance in the globalization

This double movement of valorization/devalorization and of Autonomy/control, we continue to find equally in history and in the practices of distance education.

Practice, traditionally known with the term “teaching by correspondence”, the distance formation initiates the flight through the impulse, among others, from the transformation of knowledge in products of consumption in all stages of life; the massive arrival of adults to the market of education continue; from the breaking of the borders that are linked to the interest of a great diffusion, an international vision of knowledge and of the products of teaching; of the development of technologies of information and communication; and of nature of the dominion that facilitates the autonomy and the flexibility of its use.

At present distance formation is in full expansion in North America, as well as in other parts of the world:

-

Colleges and universities possess departments « at a distance » that moderate the present courses, or

-

They create their own distance courses;

-

Professors interested in Internet use especially to broadcast documents and frame them;

-

Students;

-

The companies and the public and private organizations favor the perfecting of its personnel and they privilege distance education;

-

The distance formation becomes converted in a field of collaboration: the institutions, the organisms or the companies regroup to enjoy from their mutual strengths and complement their weaknesses within the conception, the production, the diffusion, the frame of the formations.

To understand this movement all the way through, that touches at the same time, the present formation and at a distance, I orient the analysis with the help of an articulated layout on two axes: distance-proximity and control-autonomy.

During the last century, the term teaching by correspondence was replaced by distance education. This replacement evokes two big transitions in the last two decades. In the first place, it transfers an “instructive” paradigm to the teaching against the paradigm focused more amply on the student. As a consequence this means is dominated by the discourses on the constructivist focus, just as is this one of the educational technologies. (These focuses are the object of a reflection in the fourth part of the text.) At once, the transference of a printed paradigm (correspondence) against the means of technological diffusion (progressively supported in a numeric way): Quicker, more eclectic, more oral and visual (audio and videocassettes, audio and tele-conferences, computer, Internet, etcetera.) and above all, multidirectional.9

Distance education is observed on two axes (see Figure 1) that, allow to describe the field and locate the big challenges that the evaluation presents. On the first axis, that emanates from the teaching/learning field, rests the continuous control/autonomy. This one is fundamental in all aspects of teaching/learning. In between the cause within the nature of knowledge and of its consequent educational, psycho-social theories, these knowledges, are they perhaps preconstructed by the student like the vote that brings near the instructivism that controls the content and the result of the apprenticeship? Or can they be moldable and built by the student in an autonomous and individual process in the creation of knowledge? This axis also permits situate the process of transmission/acquisition, especially in practices just as the design of the pedagogic material and evaluation. It also explains the student-institution relationship. This axis analyzes, therefore, the educational dimension of distance education.

On the second axis, that emanates from the field of technologies, is situated the continuous distance/proximity. The devices of distance education, that rest essentially on the reality of the distance, in time and space, are gradually put into proximity by the technologies of the communication; These have passed from a unidirectional mode to a pluri-directional one. The present teaching adopts also a part of distance education with the videoconferences, the satellite transmissions, and over all with the Internet. This axis allows us to examine the rational dimension (pedagogic and socio-cultural) of distance formation in a continuum, where on one hand unidirectional technologies keep the distance, in time and space, meanwhile the pluri-directional technologies annuls it and transforms it.

Figure 1. Tandems of control-authonomy and distance-proximity

The evolution of distance education is initially tied to the development of technologies and the distancing of the controls towards a major autonomy. There are three models of distance formation (Sauvé, 1990), that correspond historically to the same number of generations of development and of diffusion of technologies of the communication. These go accompanied, and in turn accompany three cognitive focuses of teaching/learning. The superposition of the technological models and the cognitive focuses are not, of course, standstills as long as each stage of the development is, so to say, “contaminated” by the thought that preceded it and in inclusive the precursors of the movements that survive. What’s more, the previous practices persist a long time after having introduced the new.

The first generation born with the invention of a technology of distance communication was the postal system and the bells. It was especially in England and in the United States that teaching “by correspondence” peaked at the end of the XIX century. It was the dream of progressive commercial character in light of the technical and professional dominion. The means used then were simple: written (printed on paper or manuscripts) and the post. Their methodology was a replica of the magisterial teaching having as a background a cognitive model of the transmission of knowledge: Instructivism. This one refers to the historical, educational paths that, based on positivism, wish to inculcate the preconstructed knowledges, independent of the student or of its own situation.

The second generation, around the years 1950-1980, was marked principally by the inclusion of systems that combine diverse methods: writing, radio, television, cassettes, them being either audio or video, telephone, etcetera. After the Second World War, teaching at a distance was transformed profoundly. First of all, it was made democratic. From a marginal public in its beginning, distance education transformed itself, and increasingly began to respond to interests and the necessities of a demanding population of permanent education, making consumption and commercialization of knowledges, surge. Throughout the whole world, many institutions of distance education began to open, to respond particularly to those adults in permanent education.10

During this period, the evolution is shown on several layers: from the professional education to the higher education; from the private sector to the public subsidies; from printed paper to the creation of multimedia devices. These evolutive stages have provoqued that the student loses his o her capacity of choosing between an education of smaller scale and an effective system for a large number of people and based on the accessibility to the studies. The valid cognitive model is therefore principally constructivist, accumulative and instructivist. In the manuals and in the notes of the courses exercises, particularly of the question/answer type are included.

The third generation is recent. It includes interactive multidirectional technologies: a pedagogic direct communication between the student and the teacher, between the students, or of the pupils with the means of learning. In societies where individualism is a fundamental value, the constructivist’s pedagogies gain major importance. The knowledges, below the constructivist inspiration, are of a progressive nature, at the disposition of the learning and the autonomy of the students. These developments demand important investments. The preceding period had originated the birth of individual institutions, that organize and regroup institutionally and in nets. These serve for the diffusion of common or parallel courses or for professional help.11

In Canada, there exists at present three unimodal institutions specialized in distance education: Open Learning Canada (http://www.ola.bc.ca/ola.html) of British Columbia, the Télé-université du Québec (http://hvfflv.uguebec.ci) and the University of Athabasca in Albert (http://www.athabascau.ca). There also exist equally 25 universities and Cegeps12in Québec that are bimodal and that offer courses and programs reserved for adult students.

The bimodal institutions, in general, have the tendency to develop courses of distance formation with supports that complement the present teaching (multidirectional or interactive videoconferences, videography, Internet, videocassettes of present courses) while the unimodal institutions move away a lot from the present or choose other multimedia support including the telephone, audio-conferences, Internet, as well as audio and video cassettes. These last ones give a great importance to the preparation of the pedagogic material.

During said pedagogic advances at a distance, how can we qualify the acquired competence during the learning? Around this question lies the trickiest challenge of the institutional control.

Traditionally, the questions on the security or fraud (understood as the degree of institutional control) have frequented the formation at a distance. How can we be sure that it is the student the one that responds to the telephone call, the one who sends his work and the one who enrolls in the courses? Certain institutions of distance education established on-site exams to resolve this problem. Therefore it is paradoxical to believe that by seeing the student (by his/her presence) is to know the student and that the present evaluation is more valuable than the one carried out at a distance, at least for the languages. As an example, in ten years at the Télé-université we did not have a single evident case of fraud. Other insistences demonstrate the same situation in the Distancelearn-lang, a forum of discussion on the distance formation in languages. An educator in this institution indicates that he knows his students by means of regular contact, the comments that are said, the work corrected and certain forms of encounter. As a matter of fact, adult students generally are so motivated by the content of the learning that this interests them more that obtaining the diploma.

The comprehension of the question on the validity of distance learning rests at the heart of the control, that the present institutions practice traditionally on the students, and the development of the autonomy that the institutions at a distance has as privileges. To judge the value of the diplomas it would then be necessary establish uniform basis of philosophy of the education on the continuous control/autonomy, constructivism-instructivism.

Also, the challenges that represent the evaluation of a student in his o her autonomous journey on distance education, can be identify in two levels, those of the objectives and those of the means. In the first place, why evaluate? The evaluation traditionally permitted to verify the advances in the accomplishments of the student, comparing it with the others, the officializer of the apprenticeship. The concepts of the formative evaluation or of the monitoring (Dickinson, 1987) were developed in contact with the transition towards the constructivism; the evaluation acquires a role of internal control (for the student) as well as external (for the institution). With the advent of the autonomous journey, the necessity of the external formal evaluation has even still other actual structures (and future) of recognition of the formation; an institution signs a diploma, attests to a number of credits, official symbols of knowledge. Therefore these same institutions are given increasingly the role of service in relation to the objectives of the students. What practice must then we adopt?

On one hand, if an autonomous journey permits the student choose his/her own objective, in relation to his/her own interest, motivations, experiences, level of competence, it appears to me essential in defining two stratums superimposed of objectives. First, it deals with programming a journey with minimum objectives that would respond to the institutional exigencies, according to the desired competitive level (intermediate 1, 2, etcetera). The second stratum would understand the individual objectives. The suggestion of the journey is converted then into a mixture of the two stratums.

On the other hand, it also appears necessary maintain the formal moments of the evaluation through diverse methods. The telephone is a very efficient tool. Contrary to the ideas received, the phone evaluation favors the spontaneous interchanges just as much as the on-site education does, but preserves the physical anonymity (distance) in such a way that the student never feels judged in his person nor in his voice. Moreover, the phone conversation strips the communication of its para-linguistic aspects. An interchange under the form of synchronized discussion in group is required. These are two means of evaluation that the distance formation can use as a gain, besides the traditional exams, corrected be it automatically or manually.

But, these two suggestions must be accompanied by the process of learning and of its evaluation. In transference of control towards the autonomy, the last bastion of control is the evaluation that also must be transformed: towards practices to learn how to auto-evaluate/appreciate itself and to evaluate our societies in function to the values of the solidarity.

Conclusion: Evaluate to better build an ensemble of practices and of values of solidarity and of respect

To complete this baggage of ideological and pedagogic reflections and to put into context the formers of the apprenticeship of the solidarity, it is still important provide forms of evaluation of the actions analyzed or projected, them being individual or collective. I wish to complete this tour of the panorama of the evaluation with a group of questions to understand the origin, it being concurrent or solidary of the projects and of the reflections.

Table III. Tools of evaluation of the ideologies and of the contemporary projects and its effects on the conditions of collective and individual life

I propose you this, hoping that we can carry out another paradigmatic interchange at the beginning of this XXI century, that it may lead us to an evaluation, for distance education, of our projects and values towards the valuation and the autonomy.

References

Birke, L. & Hubbard, R. (1995). Reinventing biology. Respect for Life and the Creation of Knowledge. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Blanke, H. (1996). Marcuse’s discourse on nature, psyche, and culture. In M. David (Ed.), Minding nature. The philosophers of ecology (186-208). New York: The Guilford Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1998, Agust). De la domination masculine [Versión electrónica]. Le Monde Diplomatique, p. 24. Retrieved November 5, 2003 from:

http://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/1998/08/BOURDIEU/10801

Brookfield, S. (1995, June 20). The getting of wisdom: What critically reflective teaching is and why it's important. Retrieved November 5, 2003 from:

http://www.nl.edu/ace/Resources/Documents/Wisdom.html

Dickinson, L. (1987). Self-instruction in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gould, S. J. (1993). Eight little piggies: reflections in natural history. New York: Norton.

Macauley, D. (1996). Minding nature. The philosophers of ecology. New York: The Guilford Press.

Martel, A. (1999). Formation et technologies en Amérique du Nord: carrefour de mise à distance et de proximité pour les langues. Études de linguistique appliquée, Didier Érudition, 113, 13-30.

Martel, A. (2000a, September). L’apprentissage des langues par Internet. Transition par les technologies de communication. Intercompreensão-Revista de Didáctica das Línguas, 8, 121-138.

Martel, A. (2000b). Constructing learning with technologies. Second/foreign languages on the Web. Retrieved November 5, 2003 from:

http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/michaelwendt/

Seiten/Martel.htm

Maulini, C. (1996). Qui a eu cette idée folle Un jour d'inventer [les notes à] l'école? Retrieved November 5, 2003 from Université de Genève, Faculté de psychologie et des sciences de l’éducation Web site, from:

http://www.unige.ch/fapse/SSE/teachers/maulini/note.html

Ministère de l'Economie, des Finances et de l'Industrie (s.f.). Glossaire de la formation à distance. Retrieved November 5, 2003:

http://www.telecom.gouv.fr/form/form_gloss.htm

Nunan, D. (1999). Second language teaching and learning. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Sandholtz, J. H., Ringstaff, C. & Dwyer, D. C. (1997). Teaching with technology. Nueva York: Teacher’s College Press.

Singer, P. (1991). Animal liberation (2nd. ed.). New York: Avon Books.

Tollefson, J. (1991). Planning language, planning inequality. New York: Longman.

1 Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa thanks Coordinación General del Sistema para la Innovación del Aprendizaje, INNOVA (General Coordination for the Learning Innovation System) of Universidad de Guadalajara (University of Guadalajara), organizer of the XII International Encounter of Distance Education, for letting us publish this key-note lecture.

2 On the other hand we know that this way of looking at living beings is basically wrong and that our solidary societies exist among the animals as much as in humans but that science has ignored them in their totality due to the fault of the ideologies and the competence. See Birke & Hubbard (1995) and Singer (1991).

3 Or also, we know that this way of observing living beings is principally false and that solidary societies exist among the animals as much as in humans but that science has ignored them in their totality due to the fault of the ideologies and the competence. See Birke & Hubbard (1995) and Singer (1992).

4 [Editor’s note] The author uses this french word to describe what Kenichi Ohmae pointed out in 1985 about the consumer groups of the Inter linked Economy (ILE) of the Triad (United States, Europe and Japan), that are becoming more homogeneous.

5 In this article, behavior is considered as forming part of the instructivist theories because, like these last ones, favors an authoritative role on behalf of the educator/programmer.

6 To see the references on constructivism and its pedagogic applications see:

http://www.stemnet.nf.ca/~elmurphy/emurphy/refer.html

http://carbon.cudenver.edu/~mryder/itc_data/constructivism.html y

http://thorplus.lib.purdue.edu/~techman/conbib.html

7 In this article, the behavior is considered as an integrative part in the instructivist theories because, like these last ones, they favor an authoritative role on behalf of the educator/programmer.

8 Table III is a picture of the work for the preparation of the course “LIN 4121 Didactique du français langue seconde/étrangère par les technologies” (Didactic of French as a second foreign language by the technologies) of the Télé-Université under the guidance of Angéline Martel. Table IV is also a picture of the work for a course on intercultural communication on track of the preparation for the Télé-Université.

9 I adopt here a great conception of distance education to include the formation in an institution (private or public) be it whichever and without considering the means of diffusion and communication with which the present education counts on or those solely destined to distance education. The interest in maintaining this field of investigation ample is to try to understand the phenomenon of distance education in the field of languages, not that it is in particular, by reference of teaching, at present, but rather in denouncing the continuum in a context of blurring of the borders between the distance and the presence.

10 L’UNISA in South Africa in 1951, in the 60’s the universities “without walls” in the United States sustained by the Carnegie Foundation, the radio-television network NHK in Japan; the Tele Kolleg in Germany. There comes then a vague reaction of unimodal universities specialized en distance education: the Open University in England in 1971; the Télé-Université in Canada (Québec) in 1972; the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (National University of Distance Education) in Spain in 1973; the University of Athabasca in Canada in 1975; the Allaman Iqbal Open University in Pakistan in 1975; the Hagen Fernuniversitat of Germany in 1975, the Everyman’s University of Israel in 1976, and others. The context of unimodal functioning regularly permitted these institutions develop the models of formation that emphasis the design of the pedagogic material known for the distance education. On the other hand, the universities that teach in a face-to-face way are involved in distance formation to respond to the necessities of a distant public: Deakin University and the University of Queensland in Australia are the first examples. These bimodal establishments are developed at the same time in Canada beginning with the Memorial University in Newfoundland. In 1967, the University of Waterloo in Ontario in 1968, the British Columbia Institute of Technology in 1974.

-

The Réseau d'Enseignement Francophone à Distance du Canada (REFAD) [French Leanguage Distance Teaching Network of Canada], (http://www.refad.ca). Since 1988, the net of distance teaching in French in Canada, reunites people and organizations interested in promoting and developing the education in French through distance education. They publish a repertoire of distance courses and a bank of proficiency for the professional perfectioning in distance formation offered on the Internet.

-

The Association Canadienne de l'Éducation à Distance (ACED) [Canadian Association for Distance Education], (http://www.cade-aced.ca). Founded in 1983, the Canadian Association of distance education, it is a National Association of Professionals where the purpose is to promote distance education. It foments the investigation on the theory and methods of distance education, provides its members services of activities of professional perfectioning, it serves as an interchange forum and of interaction in the national, regional, provincial, and local levels.

-

The National Technological University (http://www.ntu.edu). Founded in 1984, it regroups 48 universities of good reputation and big American companies. It offers more than 500 courses in direct (via satellite) or through videoconferences around more than 1000 sites around the world, therefore, these courses are in the Japanese, Chinese, and German languages. Its means are complemented by video numeric courses, with videocassettes, with audiocassettes, with the mail, with electronic conferences.

-

New Promise, of Cambridge, Massachusetts (http://ivfflv.caso.coni/index.htn-U). It provides an index of courses offered through Internet. This one contains more than 100 institutions; more than 3,000 courses. (In languages, one finds 18 courses offered In English, 13 in French, 7 in German, 2 in Italian, 10 in Latin, 4 in Russian, 25 in Spanish, and 28 in other languages).

-

The Consortium International Francophone de Formation à Distance (CIFFAD) [International Francophone Consortium of Distance Education], (http://ciffad.francophonie.org). Founded in 1987, the Consortium international francophone de Formation à Distance is a net of institutions of distance education in French. Provides information on the formation of those who speak French, establishments, courses/programs; help/products, proficiencies/personal resources) for the teaching in French. It favors the formation of nets.

-

La Commonwealth of Learning (COL), (http://www.col.org). Founded in 1987 by the countries belonging to the Mercomún, the COL favors the development and sharing pedagogic material recognized by distance education, the experience, the technologies, and other resources en all of the Mercomún and with other countries.

12 The Cegeps are [the acronym to identify] the general and profesional teaching colleges in Québec, these colleges offer education after the 11th. grade to students who want to become profesionals (technicians) and to educate them in a university level education in a minimum of two years.

Please cite the source as:

Martel, A. (2004). Individual and social assessment in a global distance education era. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 6 (1). Retrieved month day, year from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol6no1/contents-martel.html