Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 6, No. 1, 2004

A Way of Processing the Information in

Scientific Textbooks and its Influence

on Comprehension

Miriam Carranza

(*)

carranmi@hotmail.com

Gabriela Celaya

(*)

gabrielacelaya@hotmail.com

Julio Herrera

(*)

jherrera@com.uncor.edu

Fernando Carezzano

(*)

fercarezza@yahoo.com.ar

*

Cátedra de Morfología Animal

Escuela de Biología Facultad de

Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba

Av. Vélez Sarsfield 299, 5000

Córdoba, Argentina

(Received: March 18, 2003;

accepted for publishing: December 2, 2003)

Abstract

Students who can meet the demands of academic discourse develop cognitive and metacognitive skills with which to understand the information they get from reading scientific texts, and thus establish their learning. In this work, a group of university students were evaluated concerning their competencies and deficiencies in the reading comprehension of a fragment of a scientific text used in one of their courses. The results allowed us to assess the most frequent difficulties in processing information and in understanding what they read. The group was made up of a few students skilled in reading comprehension skills, plus several inexpert readers with little capacity to monitor and assess their own understanding.

Key words: Information, texts, comprehension, higher education.

Introduction

A review of the last fifty years’ research on reading comprehension reveals various theories about the reading process (Dubois, 1991). For some authors, the reader understands a text when she can recognize the meaning of the words and sentences that constitute it; for others, understanding comes when the information contained in the text is integrated with the reader’s prior knowledge or schemata, and influences the comprehension process (Rumelhart, 1980, Anderson and Pearson, 1984). The latter point out that the reader tries to find appropriate ways to explain the text and make sense of the information (Quintana, 2000); when the new information is received, the patterns are restructured, adjusted and perfected. Reading also is perceived as a process of transaction between the reader and the text (Rosenblatt, 1976), and the meaning extracted from the latter will depend on the transactions produced between the reader and the text in a specific context (Cairney, 1992).

Currently, education researchers define reading comprehension as the technique of producing the meaning of the relevant ideas of the text, and relating them to ideas the reader already has, a process in which the reader interacts with the text (Otero, 1997; Campanario and Otero, 2000; Sánchez Miguel, 1993; Macías Castro and Maturano, 1999).

Numerous studies have addressed the issue of reading comprehension from different perspectives and with different aims, such as diagnosing the predisposition of students to read (Cadile and Cadile, 2002), analyzing and evaluating reading comprehension skills (Otero, 1997; Macias, et al., 1999; Martínez, Montero and Pedrosa, 2001), determining the factors that affect understanding (Macías, et al., 1999; Otero, 1990; Alliende, Condemarín and Milicic, 1993) and the mechanisms that operate in that process (Areiza and Henao, 2000b). There are also those who develop models, procedures and strategies to promote reading comprehension (Alzate, 1999; Bernard, Feat, San Ginés and Sabido, 1994, Izquierdo and Rivera, 1997). Most works are oriented toward the problem of comprehension in early and middle levels of education. Few studies address the issue in higher education (Macias, et al., 1999; Greybeck, 1999, Contreras and Covarrubias, 1999).

In higher education, specific disciplinary content is transmitted, and it is understood that students must “comprehend or understand” the contents of the texts (Carlino, 2002), i.e. university students must (or should) have the ability to interpret conceptual subtleties and implications, and to construct new semantic networks that take metatextual and intertextual competency into account (Areiza and Henao, 1999). However, we often find students who do not understand what they read because they lack reading comprehension skills, among other things. This is reflected in their limitations regarding the generalization or transference of what they have learned to situations other than those which gave rise to their learning (Vargas and Arbeláez, 2001).

In this sense, Areiza and Henao (1999) emphasize the fact that many cognitive and metacognitive skills involving complex mechanisms are deployed at the end of high school and even in graduate school. These competencies would be achieved in a later stage of intellectual development (Ugartetxea, 2001), which is why teachers of higher education should know their students’ skills in reading comprehension. Deficiencies in this field prevent students from meeting the demands of academic discourse and work rhythms. Some educators do not recognize that the reading and writing tasks they require are part of the academic practices inherent in the mastery of their discipline (Carlino, 2002).

Martinez, et al. (2001) have pointed out that 82% of educators report comprehension problems in Argentine public school students. This is the result of small amount of time they spend reading, since some high school students spend less than two hours a day in reading any type of printed material (Cadile and Cadile, 2002). As one may expect, inexpert students will be disadvantaged in confronting upper-level studies, since reading and understanding to build the overall meaning of the text is a priority skill that must be mastered, as it is the basis of learning and culture (Paris, Lipson and Wixson, 1983).

Background

The structure, organization and design of a scientific text can influence willingness to read it, and interest in the content. The contribution of the texts to the process of teaching and learning a discipline can be evaluated through criteria that allow its analysis and comparison. In previous works we analyzed the dimension of quality, the usefulness of scientific texts (Carranza, Celaya and Carezzano, 2001, Carranza, Celaya, Carezzano and Herrera, 2002) employed in the teaching and learning of different subjects of the degree program in Biology.

After an iterative process of testing and adjustments to the survey model used to analyze printed texts (Carranza and Celaya 2002; Herrera, Carranza and Carezzano, 2002), we detected in students certain difficulties concerning how to explore and operate with scientific books; this affects academic performance. There were differences in reading comprehension between groups of students in the basic stage and those in the upper level of the program. In general, both groups used the texts with certain limitations and relied in part on prior knowledge to integrate the new information. Textual and cognitive competence was partially developed in the basic cycle. As we have pointed out in another study, upper-level students evaluated and monitored their understanding better; however, they developed metacognitive strategies when there was a significant intervention by the teacher (III Congress of Anatomy of the Southern Cone, 2002).

Conceptual Framework

The specific type of mental operations used by a good reader depends largely on the structure of the texts (narrative, expository or scientific). The skilled reader is able to recognize the type of text he is reading, and in this way, updates and expands his network of conceptual schematics. This implies that for the text he must develop a meaning that includes the author's intentions, and must begin a process whose development makes the difference between a good reader and one who is not expert (Godoy, 2001).

Pearson, Roehler, Dole and Duffy (1992) have shown that competent readers possess defined characteristics, among which are notable: a) their use of prior knowledge to make sense of what they read; b) their assessment of their understanding during the entire reading process; c) their performance of the necessary steps to correct comprehension errors when dealing with misinterpretations; d) their distinguishing what is relevant in the texts they read, and summarization of information; e) their constantly making inferences, i.e., they have the ability to understand some particular aspect of the text based on the meaning of the rest (Anderson and Pearson, 1984); f) their formulation of predictions, developing logical and reasonable hypotheses regarding what they are going to find in the text; g) their asking and taking responsibility for their reading processes.

Problems concerning the comprehension of texts are (Benito, 2000):

- The difficulties of operating with the information in the text. The immature reader often processes it in a linear manner, and has trouble identifying global aspects within the text.

- Deficiencies in evaluating and regulating their own understanding. Inadequate control prevents the reader from identifying discrepancies between the scientific information a text provides, and inappropriate concepts the text may contain.

Understanding a text is an activity guided and controlled by the reader, but in very few cases the construction of knowledge is observable as self-determined, which means that the teacher’s involvement is required for the student’s approach to the book (Macias, et al., 1999). The cognitive resources themselves are deployed in facing the need to resolve situations or problems. The degree of awareness or knowledge individuals possess concerning their cognitive processes is a metacognitive activity (Flavell, 1976, Vargas and Arbelaez, 2001). Metacognition makes it possible for the individual to acquire knowledge, as well as to use and control it (Vargas and Arbelaez, 2001). There are two levels in this process: knowing the purpose of reading (why one reads), and auto-regulation of cognitive activity to achieve that goal (how one reads). The way in which the method and its regulation are carried out is determined by the reasons for reading (Contreras and Covarrubias, 1999). Metacognitive competence is the link between semantic memory (accumulated during the pedagogical cycle) and procedural memory (which permits the operation of changes in the conceptualization processes) which enables the reader to attain higher levels of knowledge (Areiza and Henao, 1999).

Work Methodology

We worked with a group of fifth-quarter Biology students from the National University of Cordoba (NUC), Argentina, in 2001. To assess their competencies and possible deficiencies in reading comprehension, these students were asked to make an analysis of an excerpt from the book Invertebrate Zoology, by Barnes (1989); this book was used in a specific course. They were given a test paper with a 252-word passage about “Coelom”; the passage was transcribed verbatim, and was organized into three paragraphs. This topic, proposed by the teacher in charge of the class, represented a previous taxonomic and evolutionary value concept which the learners had acquired in the course they had taken earlier as a prerequisite for their present class, and which they had to apply and integrate into their present course contents.

In compliance with the guidelines established, the students/readers had to carry out the following activities: 1) Write an appropriate, complete and representative title for the fragment. These adjectives were defined as: appropriate, including terms that indicated the main idea; complete, distinguishing the most relevant aspects of the main idea, and representative, referring to the overall structure of the topic. (Regarding the subject matter of the text, they had to include terms or synonyms for body cavity, structural diversity, metazoans). 2) Underline the main idea(s) and enclose the subordinate ideas in parentheses. 3) Make a five-line summary, which should be: coherent, complete and not exceeding the length designated; i.e., state the most important ideas in the text, with the main idea and the subordinate ideas in logical order and sequence according to priority; the statements of the ideas had to contain the most important aspects of the topic. 4) Select five key words representative of the subject treated, without redundancy or errors. 5) Detect possible inconsistencies in the text. Regarding the latter activity, there was deliberately introduced a sentence inconsistent with 31% of the evidence submitted. The inconsistent element was added at a point followed by the two last lines of the second paragraph, and said: “...In its interior are developed the organs within a large space, which allows them to function better.” This statement, related to the concept of the coelom, was placed immediately following the definition of acelomates (organisms without a coelom).

The material was distributed to 50% of the total student population (95), and the data presented are for 20 students who voluntarily took the test. Those who did not take it argued that analyzing the text fragment was too time-consuming for them. The test was given after the last partial evaluation of the course when, supposedly, there was greater interaction between students and textbook. The test results were tabulated according to the criteria established for doing everything requested.

Results and discussion

The text fragment analysis results belonging to 20 students (21.05% of total population) are shown in Tables I, II and III.

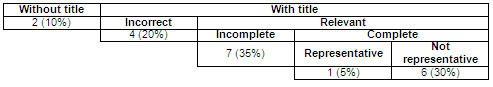

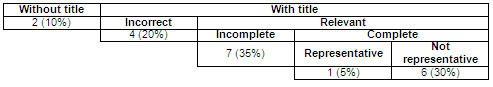

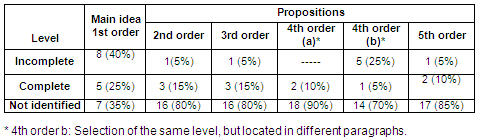

Most of the students included a title to the piece, but only one met the three conditions: that the title be appropriate, complete and representative. The remaining gave the fragment appropriate titles, and approximately half of the titles given were complete. Four students wrote incorrect titles: two people used elements of the secondary idea as part of the title. The rest incorporated inconsistencies, demonstrating an incorrect use of terms and therefore, of concepts; for example, including metazoans and flatworms, or referring only to invertebrates or alluding exclusively to the role of intracavitary fluid (see Table I).

Table I. Number and percentage of students who gave a title

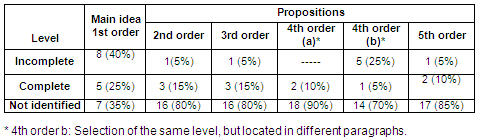

The text recognized a main or central idea and numerous subordinate propositions (see Table II). Of the latter, there were computed hierarchically those of second, third, fourth and fifth order according to their relevance in the text. As shown in Table II, 13 students recognized the main idea of the text, but 8 of them did so improperly. In some cases pupils added elements of the proposition of the second order to the central idea, while others fragmented the main idea. Five students identified it correctly, and a lesser number fully recognized the other proposals, according to their relevant hierarchy. The proposition of the fourth order (b) was identified by several students, albeit incompletely. In this regard, it is worth noting that the ability to organize and hierarchize ideas is what makes it possible to glean what is essential from a text to facilitate its storage in the memory (De Zubiría, 1997).

Table II. Number and percentage of students who identified

the main idea and the subordinate ideas

According to preestablished criteria, fifteen students (75%) wrote a summary. Of that number, three (15%) had the requisite features: they were coherent, comprehensive and of appropriate length. Many wrote their summaries using the strategy of copying extracts. While most of the summaries did not exceed the available space, some showed a lack of consistency (5-25%) and other misconceptions incorporated (2-10%). Two students (10%) did not write a summary; instead, they produced a conceptual plan through the association of terms. Those students who proceeded correctly applied cognitive and metacognitive skills to understand what they read. These were evidenced by the unity, coherence and overall sense of the summary, where they had to rank the ideas using the central proposition as a basis for understanding them (Dijk, 1989).

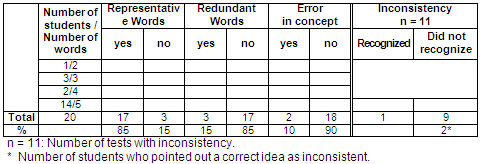

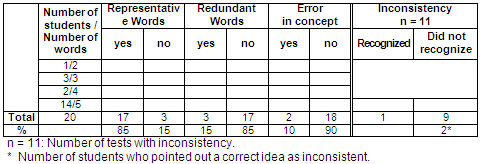

Following the instructions, 14 students chose five key words, and most incorporated representative terms, non-redundant and without conceptual errors (70%) (see Table III). Some (15%) introduced representative words, redundant and vague in concept (10%). Those who chose fewer than five words did so in an appropriate manner.

Of the total number of tests taken, 11 included one notable inconsistent statement. Only one student was able to detect it (5%); for the rest, it went unnoticed. Among these, two students identified as inconsistent propositions that were correct, although one of the proofs did not contain the inconsistency.

Table III. Number of students who followed the instruction regarding key words and detected the inconsistent proposition

The processing of this information should be easy for students, since most of the concepts were developed in a course in the fourth quarter, taken up again to integrate new knowledge on the subject during the fifth semester, and especially when the course evaluations had been concluded. Among the students who completed the test as directed, there were those who showed difficulties in ranking the ideas and differentiating the main proposition from the secondary ones. Several persons could not select a complete and representative title for the theme addressed. They found it difficult to identify clearly the central theme of the piece and its most significant elements. They did not use their prior knowledge to recognize the structure of the text and reflect it in the summary. In addition, many were unable to identify the inconsistency. Everything indicated that they were deficient in their ability to evaluate and regulate their reading comprehension.

The goal determines what skills and capabilities must be brought into play when reading. A text is not read in the same way if the purpose is to pass the time as it when the aim is to identify main ideas, search for the best title, draw conclusions or make a critical assessment of it. A good reader uses mental processes that allow him to identify the structure of the text and to update his plans (Contreras and Covarrubias, 1999).

Understanding what is read in the scientific text analyzed here, despite the lack of a good adaptation of the original English version implies that the subject remembers what she already knows, to update and expand the conceptual network. When previous ideas about a particular topic are not evoked, there are no schematics available for activating specific knowledge, and therefore, understanding will be difficult or even impossible (Quintana, 2000). Our results show our pupils’ most significant difficulties in understanding texts. These are related to difficulties in the way of assimilating the information the text provides, failures in recovering previous knowledge and the lack of self-regulation in the comprehension process.

Students who fragment the information they get from reading find it difficult to select from their prior knowledge the most relevant elements to use in integrating new information. Then, it is impossible to locate the source of their difficulties, and finally, they do not detect the signs of a lack of understanding. Consequently, they are not able to analyze information in the text or activate the significant knowledge (Benito, 2000).

Conclusions

This study provides an overview of competencies and deficiencies in reading comprehension in this group of third-year students in the UNC’s basic cycle of Biology. The group is composed of a few competent readers, and others who still show themselves to be inexpert. The reader with specific formal education, and who is concerned with the reading of scientific texts must be able to identify the author's communicative intentions, as well as to recognize and rank the propositions according to priority. In the set of propositions, he should also differentiate the main idea containing the subject, from those whose function is to present, extend, support or exemplify it. In this way, he can enrich his cognitive schematics and increase the number of inferences, which will facilitate new readings and improve his intertextual competence (De Zubiría, 1997; Areiza and Henao, 1998, 1999, Contreras and Covarrubias, 1999).

The results indicate that some students have not yet reached this level of reading comprehension, defined by De Zubiría (1997) as elementary reading of tertiary decoding. Such a situation should cause reflection on the part of university teachers who thought that their students “must understand” the specific disciplinary content in scientific texts.

Understanding is not an all-or-nothing process; students can understand in part, to different degrees, or completely. They may also be repeatedly committing certain types of errors (Contreras and Covarrubias, 1999).

The loss of the reading habit in young people may be associated with multiple causes, among which are mentioned disinterest, lack of motivation, socio-economic decline, changes in values and advances in technology.

Recently, in Argentina there have emerged concerns over the lack of reading comprehension skills in students of basic education, as reported by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), (“The Social Gap”, 2003). The specialists relate these issues to the low investment in education in all the countries of Latin America.

In another order of ideas, technologies such as books, movies, television, video and computers, have been incorporated naturally and gradually into the educational process (González Pérez 2001). However, the impact the computer has had in our society has given rise to very different and contrasting opinions. Thus, for some educators, the computer is a tool that does not work to the extent expected in the overall development of language skills (Greyback, 1999).

The problem could be related to the educational context and the capabilities of those who plan the goals and activities to be used on the computer. While it is accepted that the proper use of new computer and communication technologies (ICTs) can implement pedagogical principles for those in which the subject is the protagonist in the construction of knowledge (Waldegg, 2002), in some Argentine junior high schools, the computer has a limited impact on educational development and students’ daily work. Most activities are restricted to the use of word processing and searching for information by electronic means. This scarcely encourages the development of strategies to help overcome the problems of concept comprehension (Martínez et al., 2001). On the other hand, outside school, many young people spend much of their time in businesses that provide Internet service (cybers, internet cafes) and perform various activities with more attractive and participatory options (online games, chat, interaction with communications media) which do not exactly promote higher-order cognitive skills.

Currently, the development of networks with electronic support (Web) has led to a more interactive stage for the teaching-learning process. However, for Latin American countries the transition to digital information and knowledge implies economic investments that are far from matching those of industrialized countries (González Pérez 2001).

In attempting to generate interest and motivate students by using strategies commensurate with the circumstances, we developed and evaluated a CD hypertext resource on specific topics of the fourth-quarter course of that degree program in Biology. This was used by students to supplement other didactic materials, and had the aim of promoting a more participatory and active teaching and learning process. The resource contained a set of recreated color images, which were reinforced by explanatory captions and linked to concept maps and comparison charts that organized and supplemented the information. Some evaluation results indicated that as readers integrate what they already know with new concepts, they become little competent in processing information when they do not monitor and evaluate their cognitive processes. This suggests that difficulties in reading comprehension go beyond the type of resources used (Carranza and Celaya, 2003).

The cognitive configuration of an individual is built using her own conceptual structure and the semantic information she obtains from the world and the context. All this integrates her prior knowledge with a support for the acquisition of new knowledge (Areiza and Henao, 1999; Woolfolk, 1996). The reading of texts, especially scientific ones, is a key technique for recovering acquired knowledge and using concepts that activate the memory as well as the ability to reason, and to make sense of and evaluate the cognitive processes developed, that is, for expanding cognitive and metacognitive skills.

References

Alliende, F., Condemarín, M., & Milicic, N. (1993). Prueba de comprensión lectora de complejidad lingüística progresiva: 8 niveles de lectura. Santiago: Universidad Católica de Chile.

Alzate, M. V. (1999). ¿Cómo leer un texto escolar?: Texto, paratexto e imágenes. Revista de Ciencias Humanas, 20. Retrieved May 5, 2001, from:

http://www.utp.edu.co/~chumanas/revistas/revistas/rev20/alzate.htlm

Anderson, R. C. & Pearson, P. D. (1984). A schema-theoric view of basic processes in reading comprehension. In P. D. Pearson (Ed.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 255-291). New York: Longman.

Areiza, R. & Henao, L. M. (1998). Memoria a largo plazo y comprensión lectora. Revista de Ciencias Humanas, 18. Retrieved May 5, 2001, from:

http://www.utp.edu.co/~chumanas/revistas/revistas/rev18/areiza.htm

Areiza, R. & Henao, L. M. (1999). Metacognición y estrategias lectoras. Revista de Ciencias Humanas, 19. Retrieved May 5, 2001, from:

http://www.utp.edu.co/~chumanas/revistas/revistas/rev19/areiza.htm

Barnes, R. (1989). Zoología de los invertebrados (5ª. ed.). Mexico: Interamericana.

Benito, F. (2000). La alfabetización en información en centros de primaria y secundaria [Versión electrónica]. In J. A. Gómez Hernández (Coord.), Estrategias y Modelos para enseñar a usar la información. Guía para docentes, bibliotecarios y archiveros. Murcia: Editorial KR. Retrieved April 20, 2002, from:

http://gti1.edu.um.es:8080/jgomez/hei/intranet/comprensión.PDF

Bernard, G., Feat, J., San Ginés, P., & Sabido V. (1994). Caminos del texto. Granada: Universidad de Granada.

Cadile M. A. & Cadile M. S. (2002). ¿Leen, se informan nuestros alumnos? In Memorias del III Congreso Nacional de Educación y II Internacional “La Educación frente a los Desafíos del Tercer Milenio. Conocimiento. Ética y Esperanza” (pp. 221). Cordoba, Argentina: Brujas.

Cairney, T. H. (1992). Enseñanza de la comprensión lectora (Trans. P. Marzano). Madrid: Morata (Original versión pusblished in 1990).

Campanario, J. M. & Otero J. C. (2000). Más allá de las ideas previas como dificultades de aprendizaje: Las pautas de pensamiento, las concepciones epistemológicas y las estrategias metacognitivas de los alumnos de ciencias. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 18 (2), 161-169.

Carlino, P. (August, 2002). Enseñar a escribir en la universidad: cómo lo hacen en Estados Unidos y por qué [Electronic version]. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación (Secc. De los lectores). Retrieved June 23, 2001, from:

http://www.campus-oei.org/revista/deloslectores/279carlino.pdf

Carranza M. & Celaya G. (2003). Una estrategia para favorecer la comprensión y el aprendizaje en las ciencias morfológicas: Presentaciones en PowerPoint. Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 9 (2). Retrieved August 5, 2003, from: http://www.uv.es/RELIEVE/v9n2/RELIEVEv9n2_3.htm

Carranza M., Celaya G., & Carezzano F. (2001). Un instrumento para el análisis de los textos utilizados en el taller de actualización en Histología. Proceedings of the XI Congreso Nacional de Histología (pp. 114). La Rábida, Huelva: Sociedad Andaluza de Histología.

Carranza M., Celaya G., Carezzano F., & Herrera J. (2002). Evaluación del libro de texto empleado en la asignatura Morfología Animal. Revista de Educación en Ciencias, 3 (1), 24-28.

III Congreso de Anatomía del Cono Sur. XXXVIII Congreso Argentino de Anatomía. XXII Congreso Chileno de Anatomía (2002). Revista Chilena de Anatomía, 20 (1). Retrieved August 28, 2002, from: http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0716-98682002000100010&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es

Contreras, O. & Covarrubias, P. (January-March, 1999). Desarrollo de habilidades metacognoscitivas de comprensión de lectura en estudiantes universitarios. Educar, 8. Retrieved October 12, 2002, from: http://educacion.jalisco.gob.mx/consulta/educar/08/8ofeliap.html

De Zubiría, M. (1997). Teoría de las seis lecturas (Tomes I & II). Santa Fe de Bogota: Fondo de publicaciones Bernardo Herrera Marín.

Dijk, T. A., van. (1989). Estructuras y funciones del discurso. Mexico: Siglo XXI.

Dubois, M. E. (1991). El proceso de la lectura: de la teoría a la práctica. Buenos Aires: Aique.

Flavell, J. (1976). Metacognitive aspects of problem solving. In L. B. Resnick, The nature of intelligence (pp. 231-235). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Godoy, M. P. (2001). Factores influyentes en el desarrollo de la comprensión lectora: una mirada desde el enfoque de la atención a la diversidad. Santiago-Chile: Fundación Hineni.

González Pérez, O. E. (2001). Comisión III: Nuevas Tecnologías en la formación de formadores: Impactos y retos. In C. Braslavsky, I. Dussel, & P. Scaliter (Eds.), Los formadores de jóvenes en América Latina: desafíos, experiencias y propuestas. Informe final del Seminario Internacional “La formación de los formadores de jóvenes para el siglo XXI: desafíos, experiencias y propuestas para su formación y capacitación” (pp. 92-99). Ginebra: Oficina Internacional de Educación.

Retrieved May 10, 2003, from:

http://www.ibe.unesco.org/regional/latinamericannetwork/

LatinAmericanNetworkPdf/maldorepComIII.pdf

Greybeck, B. (January-March, 1999). La metacognición y la comprensión de lectura. Estrategias para los alumnos del nivel superior. Educar, 8. Retrieved October 12, 2002, from: http://educacion.jalisco.gob.mx/consulta/educar/08/8barbara.html

Herrera, J., Carranza, M., & Carezzano, F. (2002). Modalidad para explorar y operar con los libros de textos y su influencia en la comprensión lectora. In Proceedings of the III Congreso Nacional de Educación y II Internacional “La Educación frente a los Desafíos del Tercer Milenio. Conocimiento. Ética y Esperanza” (pp. 220). Cordoba, Argentina: Brujas

Izquierdo M. & Rivera, L. (1997). La estructura y la comprensión de los textos de Ciencias. Alambique. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales, 4 (11), 24-33.

“La brecha social empeora la educación” (Wednesday, July 2nd, 2003). La Voz del Interior On Line. Retrieved July 3, 2003, from:

http://www.intervoz.com.ar/2003/0702/portada/nota175721_1.htm

Macías A., Castro J., & Maturano C. (1999). Estudio de algunas variables que afectan la comprensión de textos de física. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 17 (3), 431- 440.

Martínez, R. D., Montero, Y. H, & Pedrosa, M. E. (2001). La computadora y las actividades del aula: Algunas perspectivas en la educación general básica de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 3 (2). Retrieved July 26, 2002, from: http://redie.ens.uabc.mx/vol3no2/contenido-vidal.html

Otero, J. (1990). Variables cognitivas y metacognitivas en la comprensión de textos científicos: el papel de los esquemas y el control de la propia comprensión. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 8 (1), 17-22.

Otero, J. (1997). El conocimiento de la falta de conocimiento de un texto científico. Alambique. Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales, 4 (11), 15-22.

Paris S. G., Lipson M. Y., & Wixson K. K. (1983). Becoming a strategic reader. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 293-316.

Pearson, P. D., Roehler, L. R., Dole, J. A., & Duffy, G. A. (1992). Developing expertise in reading comprehension. In S. J. Samuels y A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (2a. ed, pp. 145-199). Newark, DE: Interational Reading Association.

Quintana, H. E. (March 29-31, 2000). La enseñanza de la comprensión lectora. Paper presented at Duodécimo Encuentro de Educación y Pensamiento. Ponce, Puerto Rico. Retrieved August 18, 2001, from: http://coqui.lce.org/hquintan/Comprension_lectora.html

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1976). Literature as exploration. New York: Modern Language Association.

Rumelhart, D. (1980). Shetama: The building block of cognition. In R. J. Spiro, B. Bruce, & W. Brewer (Eds), Theoretical issues in reading comprehension. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sánchez Miguel E. (1993). Los textos expositivos. Estrategias para mejorar su comprensión. Madrid: Santillana.

Ugartetxea, J. (2001). Motivación y metacognición, más que una relación. Revista ELectrónica de Investigación y EValuación Educativa, 7 (2). Retrieved September 28, 2002, from: http://www.uv.es/RELIEVE/v7n2/RELIEVEv7n2_1.htm

Vargas E. & Arbeláez C. (2001). Consideraciones teóricas acerca de la metacognición. Revista de Ciencias Humanas, 28. Retrieved March 17, 2002, from: http://www.utp.edu.co/~chumanas/revistas/revistas/rev28/vargas.htm

Waldegg, G. (2002). El uso de las nuevas tecnologías para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de las ciencias. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 4 (1). Retrieved October 16, 2002, from: http://redie.ens.uabc.mx/vol4no1/contenido-waldegg.html

Woolfolk, A. (1996). Psicología educativa. Mexico: Prentice-Hall.

Translator: Lessie Evona York-Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

Please cite the source as:

Carranza M., Celaya, G., Herrera, J., & Carezzano F. (2004). A way of processing the information in scientific textbooks and its influence on comprehension. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 6 (1). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol6no1/contents-carranza.html