Learning and Teaching Styles in Traditional Dances

How to cite: Espada-Mateos, M., de las Heras-Fernández, R., & Fernández-Rivas, M. (2025). Learning and teaching styles in traditional dances. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 27, e15, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2025.27.e15.6514

Abstract

Teaching styles applied in physical activities and sports help in the achievement of students’ objectives and influence their motivation. It is important to know the preferences of future teachers for different teaching styles. The aim of this study was to analyze the perception of teaching styles in dance learning, and gain insight into the differences in preferences between the Practice Style and the Divergent Discovery Style. An intervention was carried out with a sample of 30 students studying for a higher vocational training certificate in sports education and recreational activities (Técnico Superior en Educación y Animación Sociodeportiva), where dances from different countries were taught with each of the teaching styles. Our conclusions point to a preference by students for the divergent discovery teaching style to learn dances and to teach dances themselves, as they believe that more freedom in learning will produce greater motivation in learners.

Keywords: physical education, dance, teaching methods, learning methods

I. Introduction

Teachers’ and students’ decision-making patterns in the teaching-learning process will determine teaching intentions, learning objectives, and learning outcomes (Mosston & Ashworth, 2008). In other words, the way one teaches affects the learning environment, which in turn can affect learning outcomes (Awally et al., 2023).

In 1966, Muska Mosston created the Spectrum of Teaching Styles, which has become a leading reference for physical education teachers, who apply certain teaching styles according to the needs of students and the objectives for the content taught. Therefore, all teaching styles without exception are useful; the use of one teaching style or another will depend on the psychomotor, cognitive, and emotional objectives established (Kyritsopoulos et al., 2023).

The premise of this theory is that teaching behavior consists of a chain of decision making (Yanik et al., 2023). “The teaching–learning behaviors within the Spectrum are tools for accomplishing the various functions of education” (Mosston & Ashworth, 2008, p.5).

Based on learners’ capacity to reproduce and produce knowledge, Mosston and Ashworth classified teaching styles into two groups: the reproduction cluster and the production cluster (Syrmpas et al., 2020).

The reproduction cluster includes styles A: Command Style; B: Practice Style; C: Reciprocal Style; D: Self-Check Style; and E: Inclusion Style; and the production cluster includes styles F: Guided Discovery Style; G: Convergent Discovery Style; H: Divergent Discovery Style; I: Learner Designed Individual Program Style; J: Learner-Initiated Style; and K: Self-Teaching Style (Mosston & Ashworth, 1993). Styles classified in the reproduction cluster are characterized by learners reproducing known knowledge and models. On the other hand, the main characteristic of the styles included in the production cluster is that the teacher guides students in the discovery of knowledge (Syrmpas et al., 2020). In these two clusters, the teacher’s and learner’s roles in learning are clearly differentiated; the process is either teacher-centered or learner-centered (Rothmund, 2023).

Given the importance of teaching styles for physical education and sports and recreational activities, it is relevant to gain an understanding of which styles are present in classes and how students perceive the teaching styles used for specific content. It is equally important to identify students’ learning styles (Romanelli et al., 2009).

There are four categories into which students’ learning styles can be classified (Alonso et al., 1994):

- Theoretical: to solve problems, they go through logical stages until they reach the solution. They are methodical, logical, rigid, objective, and structured. They are very good at creating models or theories.

- Active: they like to constantly face new challenges; they need new experiences and a constant change of stimuli to learn. They are spontaneous and play an active role encouraging others; they are discoverers, improvisers, and risk-takers.

- Reflective: to solve a problem they prefer to observe and evaluate the possible answers or options. They are thoughtful, conscientious, receptive, analytical, and exhaustive people.

- Pragmatic: before putting their ideas into practice, they will evaluate their feasibility and suitability. They are experimental, practical, direct, effective, and realistic.

Research affirms that some of the most commonly used styles in physical education classes are reproductive (styles A-E) (Aktop & Karahan, 2012; Jaakkola & Watt, 2011; Kulinna & Cothran, 2003; Cothran et al., 2005; Requena & Martín, 2015; Zeng, 2016). Zeng (2016) analyzes student teachers’ perceptions of the use of teaching styles in a physical education teacher education (PETE) program. One key finding is that they most frequently apply reproductive styles and believe that their students would be most motivated to learn with the command, practice, reciprocal, inclusion, and convergent and divergent discovery styles.

On the one hand, the application of reproductive styles will allow students to feel more competent in learning, while the uncertainty associated with productive styles makes students more insecure about whether their performance is correct (Zapatero, 2017). However, it has been observed that student motivation, both intrinsic and extrinsic, to perform tasks is greater with productive styles than reproductive ones (Real-Pérez et al., 2021).

On the other hand, de las Heras-Fernández et al. (2019) affirm that the cognitive, affective, and physical development of students carrying out dance activities will be better supported through problem-solving, achieved through the use of production cluster styles. Productive teaching styles, such as problem-solving styles or the Divergent Discovery Style applied to dance, biodanza, and mindfulness, allow students to be more involved in their own learning and therefore produce greater development, mainly at the emotional level (Constantino & Espada, 2021).

Despite this, it is important to implement teaching styles according to the needs of the content taught. Research by Villard-Aijón et al. (2013) claims that teachers prefer to use some of the productive styles to teach corporal expression content, such as the style of free exploration and problem solving, which would be equivalent to styles H, the Divergent Discovery Style, and K, The Self-Teaching Style, as classified by Mosston and Ashworth (1993). Research by Romero-Barquero (2015) notes that the teaching styles most used for popular dance content were A, the Command Style, and H, the Divergent Discovery Style, and that the application of either style and the teacher’s attitude will both influence the achievement of objectives by the student. Byra et al. (2013) indicate that the command style is not adequate to achieve dance class objectives, since this content is generally associated with cognitive engagement, for which it would be necessary to apply productive, student-focused styles such as the Divergent Discovery Style.

The fields of physical education and dance are rich in opportunities to discover, design, and invent. There is always another possible movement or another combination of movements, another dance choreography, or an additional piece of equipment. The variety of human movement is infinite—the possibilities for episodes in the Divergent Discovery Style are endless (Mosston & Ashworth, 2008).

Corporal expression content allows students to achieve physical education competences and develop aspects such as self-esteem or interpersonal relationships, in addition to allowing students’ disinhibition (Lafuente, 2022; Romero-Barquero, 2015). Specifically, traditional dances as a technique of corporal expression bring students closer to other cultures. For all these reasons, corporal expression and dance must be accorded the importance they deserve and should not be worked on solely in isolation, through the creation of choreographies (Cunliffe et al., 2011). To avoid this, it is necessary to analyze students’ previous experiences with this content; if these experiences have been negative, this will hinder their participation in tasks and decrease their motivation (Lafuente, 2022). In addition, it should be noted that a positive teacher attitude towards this content will influence students’ motivation and attitude (Arias et al., 2021; Dolenc, 2022; Romero-Barquero, 2015). The teaching styles implemented by teachers will also influence students’ motivation, as well as the learning of skills (Dolenc, 2022). Indeed, it is worth remembering that the subject taught does not always match the interests of the students, and therefore intrinsic motivation should be encouraged (Bardorfer & Dolenc, 2022). A positive teacher attitude towards corporal expression content can be achieved through adequate training of future teachers in this content (Archilla, 2013).

Objectives

- Compare preferences for the practice and divergent discovery teaching styles for learning dance, after an intervention.

- Analyze students’ perceived learning styles for learning dance.

II. Method

The present research follows a mixed methodology, combining quantitative and qualitative research techniques (Sánchez, 2015).

To achieve the first objective, the study follows a quantitative approach. We used a pre-experimental design of non-equivalent groups pre-established by their class group, with two experimental groups to which different experimental treatments were applied, and pre- and post-intervention results were analyzed (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Laher & Kramer, 2019).

For the second objective, we employ a qualitative method. Semi-structured interviews were carried out to obtain information on the students’ learning style perceptions (Ríos, 2019; Nieto, 2010). Using the Atlas.ti software and transcriptions of the interviews, an overview of the documents was obtained in order to perform basic functions such as simple coding and multiple coding of fragments (Colás & Rebollo, 1993). Likewise, another coding strategy was used through codes extracted from the theoretical framework, which facilitated the discussion of results. Subsequently, the network tool was used to create a network linking codes and families of codes, generating a concept map.

2.1 Participants

The participating subjects were 30 second-year vocational education students from the Higher Vocational Training Certificate in Sports Education and Recreational Activities (Técnico Superior en Educación y Animación Sociodeportiva, TSEAS) (see Table 1).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 9 | 30.0 |

| Men | 21 | 70.0 |

| Total | 30 | 100 |

Students ranged in age from 18 to 35 years, with a mean M = 20.20 years and standard deviation SD = 3.43 years.

The intervention was carried out in a private school providing secondary and vocational education in the Community of Madrid, in the municipality of Madrid.

2.2 Procedure

To carry out the study, four sessions were planned where the dance content was applied. Four traditional dances were taught, two from Spain and two from another country. Each session was carried out with different teaching styles, such that two sessions were taught using the practice style (a reproductive style), and the other two using the divergent discovery style (a productive style). With each style, two traditional dances were taught.

The dances used in the classes were as follows in Table 2:

| Dance 1 | Dance 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Dances from Spain | El candil (Badajoz) | Txulalai (Basque Country) |

| Dances from another country | Samoth (Israel) | Hora Chadera (Israel) |

Although the two groups that experienced the intervention were from different class schedules and there was no contact between them, a different order of teaching styles and types of dance was used for each group, as follows in Table 3:

| Teaching style | Dance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Session 1 | Practice Style | Spain |

| Session 2 | Divergent Discovery Style | Another country | |

| Session 3 | Divergent Discovery Style | Spain | |

| Session 4 | Practice Style | Another country | |

| Group 2 | Session 1 | Divergent Discovery Style | Another country |

| Session 2 | Practice Style | Spain | |

| Session 3 | Practice Style | Another country | |

| Session 4 | Divergent Discovery Style | Spain |

2.3 Instruments

The questionnaire used was on the students’ experiences with and perceptions of teaching styles (Cothran et al., 2005). Adaptation and validation for the Spanish version was carried out in order to enable its use in the context of education in Spain (Espada et al., 2021). A Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.89 was obtained in the instrument. The questionnaire included a scenario for each of the 11 teaching styles (Command; Practice; Reciprocal; Self-Check; Inclusion; Guided Discovery; Convergent Discovery; Divergent Discovery; Learner Designed Individual Program; Learned-Initiated; Self-Teaching). The internal consistency of each dimension was analyzed through Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α), the KMO test, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity.

The first dimension used in this research was the Practice Style: “The teacher establishes several stations in the gym where students work on different parts of a skill or different skills. Students rotate around the stations and do the tasks at their own pace. The teacher moves around and helps students when needed.” This dimension obtained a high internal consistency (α = .86, KMO = .81).

The other dimension was the Divergent Discovery Style: “The teacher asks students to solve a movement question. The students try to discover different movement solutions to the teacher’s question. There are multiple ways for the students to answer the question correctly.” This dimension obtained a high internal consistency (α = .88, KMO = .83).

Each scenario is a dimension followed by 5 items. These items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

In order to obtain information on the students’ learning style perceptions, four interviews were designed using semi-structured questions based on a prior bibliographical review.

Expert judgment was used to verify the instrument’s validity (Dorantes-Nova et al., 2016). The experts consulted considered the wording of the questions, taking into account that all the questions were open-ended and written in technical language, and did not eliminate or include other specific questions. The questions revolved around students’ preferences in the dance learning process, depending on whether teaching was more directed or more open, and how they felt in different physical, emotional, and cognitive dimensions.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Windows, v.27.0). Statistical significance was set at p < .05. Descriptive data are presented as percentages, mean, and standard deviation (M±SD). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed a non-normal distribution (p < .05), indicating that nonparametric statistical tests were necessary. A Wilcoxon test was performed to analyze the use of each teaching style. In addition, a two-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of gender and teaching style (with “gender” and “group” as factors) and the effect size was calculated by ηp2. The alpha level was set at p < .05.

The data analysis software Atlas.ti, version 23.1.0 (Lopezosa et al., 2022), was used for the qualitative analysis of the interviews. The questions were formulated on the basis of theories related to teaching and learning in education (Colás & Rebollo, 1993). Codes and code fragments were extracted in relation to questions that were asked about the dance learning experience. In this case, several words and text fragments linked to teaching styles (Sicilia & Delgado, 2002) and learning styles (Kolb, 1976; Alonso et al., 2005) were located.

III. Results

3.1 Quantitative Results

For the Practice Style, the students slightly decreased their score after the intervention in all items related to motivation for learning when using this teaching style, except the last item (Table 4). Moreover, there was a statistically significant relationship in this item (p = .027).

| pre M ± SD |

post M ± SD |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I had a physical education teacher who taught this way. | 2.75 ± .99 | 2.81 ± .98 | .683 |

| I intend to make use of this teaching style in the future as a PE teacher. | 3.26 ± .63 | 3.13 ± .49 | .485 |

| I think this way of teaching would make class fun. | 3.74 ± .77 | 3.71 ± .69 | .858 |

| I think this way of teaching would help students learn skills and concepts. | 3.94 ± .62 | 3.81 ± .65 | .429 |

| I think this way of teaching would motivate students to learn. | 3.42 ± .76 | 3.81 ± .60 | .027 |

Table 5 shows the results for the divergent discovery teaching style. The score increased in all items, except those related to students’ learning and motivation with this teaching style in classes, where scores decreased after the intervention. There was a statistically significant relationship in the first item (p = .001), showing that students identified this teaching style more easily after experimenting with it in the intervention.

| pre M ± SD |

post M ± SD |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I had a physical education teacher who taught this way. | 1.84 ± .73 | 2.58 ± .80 | .001 |

| I intend to make use of this teaching style in the future as a PE teacher. | 2.94 ± .72 | 3.00 ± .51 | .467 |

| I think this way of teaching would make class fun. | 3.61 ± .88 | 3.84 ± .63 | .169 |

| I think this way of teaching would help students learn skills and concepts. | 4.00 ± .73 | 3.65 ± .70 | .082 |

| I think this way of teaching would motivate students to learn. | 3.68 ± .79 | 3.55 ± .67 | .500 |

Table 6 shows how the students preferred the Divergent Discovery Style before and after the intervention, although after the intervention this preference decreased slightly.

| Practice | Divergent Discovery |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pre | 38.7% | 61.3% |

| Post | 41.9% | 58.1% |

Results from the two dimensions are presented in Table 7, with no differences either within or between styles.

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Gender | Group | Gender x Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice | 3.35 ± 0.11 | 3.47 ± 0.95 | F = | 0.38 | 1.08 | 1.51 |

| p = | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.23 | |||

| ηp2 = | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.05 | |||

| Divergent Discovery |

3.37 ± 0.11 | 3.65 ± 0.10 | F = | 1.14 | 2.94 | 0.22 |

| p = | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.63 | |||

| ηp2 = | 0.63 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

3.2 Qualitative Results

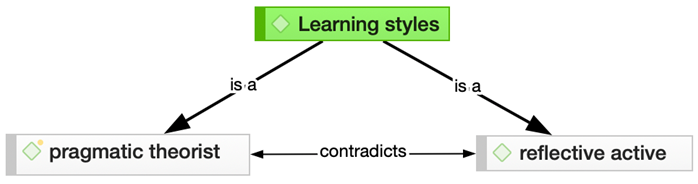

Qualitative analysis of the information was carried out with the software Atlas.ti and the categories and subcategories shown in Figure 1 were developed. The analysis made it possible to establish one main category and two fundamental subcategories in dance learning: 1.1. theoretical-pragmatic style, and 1.2. active-reflective style. These categories were extracted from the codes and code fragments generated from the analysis. Thus, it was possible to generate, as a main category, learning styles linked to Kolb’s theory (Kolb, 1976; Alonso et al., 2005), which establishes four types of learning style: active, reflective, theoretical, and pragmatic. Analysis of the students’ answers revealed the presence of these four styles, grouped in two clusters: the theoretical-pragmatic style (subcategory 1) and the active-reflective style (subcategory 2).

In category 1) learning, interviewees’ responses dealt with the form of learning that they felt best developed motor competence.

For subcategory 1.1) theoretical-pragmatic style: Some students stated that, through practice instruction, experimentation, and repetition, it was “easier to learn it” [interviewee 4, man]. This preference for learning based on reproduction and repetition of a model could fit more with the theoretical learning style (Alonso et al., 2005), in which students are methodical, logical, and structured. Moreover, many of the responses showed a relationship between this way of learning and physical education teaching styles in the same way as pointed out by Sicilia and Delgado (2002), who associate learning styles (Kolb, 1976; Alonso et al., 2005) with physical education teaching styles. Thus, students associated traditional styles with reproductive teaching styles. “The teacher directed us, she practically taught us the steps and what we had to do, I found it more educational (...) she taught us the right way to dance” [interviewee 3, woman]. Again, this statement about direct experiential practice linked to a pragmatic learning style (Kolb, 1976; Alonso et al., 2005) reflects traditional reproductive teaching styles characterized by repetition and direct instruction (Sicilia & Delgado, 2002).

On the other hand, for subcategory 1.2) active-reflective style: Some students showed a preference for more social and cooperative learning, emphasizing integration with peers and fun: “you socialize more with peers” [interviewee 2, woman]; “more freedom (...), more fun (...) decision-making power” [interviewee 1, man]. This is related to active-reflective learning styles (Alonso et al., 2005): the active learning style is characterized by students seeking practical application of knowledge; they are spontaneous, discoverers, improvisers, and risk-takers (Kolb, 1976; Alonso et al., 2005). These characteristics may also be associated with teaching styles that develop the social channel and promote creativity through problem-solving (Sicilia & Delgado, 2002).

IV. Discussion and Conclusions

This study investigated the use of the Practice Style in comparison with the Divergent Discovery Style to identify students’ perceptions of learning styles in learning traditional dance.

When students learned traditional dance through the practice teaching style, their intention to use this teaching style in their future work as teachers decreased because, after the intervention, they perceived it as a style that did not help them learn the skills and concepts, despite believing it increases motivation for learning (p = .027). However, our qualitative analysis found that to learn more effectively, some students indicated it was necessary to imitate a model. These findings are similar to those of Kılıç and Ince (2023), who found that athletes placed more value on reproductive teaching methods than other teaching styles to improve learning. Likewise, research by Brown (2021) suggests student-centered instruction may be more effective to learn dance.

Although there is a little controversy regarding the achievement of multiple teaching goals because having a model and repeating the choreography at all times gives students a feeling of ease and coordination, always working this way in education is not believed to support educational objectives linked to the cognitive channel in the areas of creation and mental engagement (de las Heras-Fernández et al., 2019). In line with the theory of constructivism, students construct knowledge based on their own experience and interactions with others (Rakha, 2023).

In research by Zeng (2016), student teachers stated that implementing certain teaching styles would motivate their students to learn better, namely the command, practice, reciprocal, inclusion, convergent discovery, and divergent discovery styles. According to Cuellar-Moreno (2016), it is important that dance teachers apply a teaching style with which they feel comfortable in order to teach the essence of dance.

It is striking how students identified the Divergent Discovery Style better after experimenting with it in the intervention (p = .001). In addition, after the intervention, they were more likely to report that they would use this teaching style in their future teaching careers, believing it can make classes more fun. Besides, previous research in the field of dance has shown that giving students more responsibility in the teaching-learning process yields better results (de las Heras-Fernández et al., 2022; Pitsi et al., 2023).

This is consistent with Nájera et al. (2020) mentioning that physical education teachers who prefer cognitive styles tend to be more supportive of students’ autonomy, since these styles promote students’ self-learning and independence, meeting the needs of students and decreasing their frustration towards physical education classes. However, Torrents et al. (2015) revealed that limitations in instructions clearly conditioned the choreographies performed by dancers, as well as their creative behavior.

The qualitative analysis shows how some students reported that with the divergent discovery teaching style, they felt more freedom and had more opportunity to socialize. Similarly, Nájera et al. (2020) noted that the creative teaching style encouraged students to think independently and offered them the possibility to express themselves freely.

Finally, the results show that the students preferred the Divergent Discovery Style to the Practice Style for learning traditional dances. In this vein, it is very important to keep in mind the perceptions of students in the teaching-learning process, since this information will enable an improved training process (Gaviria-Cortés & Castejón-Oliva, 2019).

Our results affirm that students believed the Practice Style was more effective for learning content. However, besides failing to motivate students, this style does not contribute to their cognitive development because it is based on the reproduction of models. By contrast, the Divergent Discovery Style is more popular among the students of this study, who believe that autonomy and freedom in learning will allow them to socialize more and make the classes more fun. According to Yudho et al. (2023), this increase in motivation has a positive impact on the learning process.

This freedom may influence how well dances are learned. This is why, as future teachers of physical education and sports activities, the students in this study would prefer to use the Divergent Discovery Style in their classes, rather than the Practice Style, just as they prefer the Divergent Discovery Style to learn dances themselves.

Finally, it is important to point out this study’s sample size constitutes a noteworthy limitation. For this reason, future research in this area should include larger samples and different schools, so that a greater comparison can be made.

Writing review: Joshua Parker

Contribution of each author

María Espada-Mateos: conceptualization (40%), methodology, data curation (40%), formal analysis, writing original draft (50%).

Rosa de las Heras-Fernández: conceptualization (30%), data curation (30%), writing original draft (25%).

María Fernández-Rivas: conceptualization (30%), data curation (30%), writing original draft (25%).

Declaration of no conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Source of funding

Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, project “Conocimiento y uso de la tecnología educativa en maestros y profesores de Música y Educación Física” (ID B0036).

References

Aktop, A., & Karahan, N. (2012). Physical education teacher's views of effective teaching methods in physical education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1910-1913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.401

Alonso, C., Gallego, D., & Honey, P. (1994). Los estilos de aprendizaje: procedimientos de diagnóstico y mejora [Learning styles: Diagnostic and improvement procedures]. Ediciones mensajero.

Alonso, C., Gallego, D. & Honey, P. (2005). Los estilos de aprendizaje. Procedimientos de diagnóstico y mejora [Learning styles: Diagnostic and improvement procedures] (6th ed.). Ediciones Mensajero.

Archilla, M. T. (2013). Dificultades del profesorado de Educación Física con los contenidos de expresión corporal en secundaria [Difficulties of physical education teachers with corporal expression content in secondary school] [Doctoral dissertation]. Universidad de Valladolid. Segovia. http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/4082

Arias, J. R., Fernández, B., & Valdés R. (2021). Actitudes hacia la expresión corporal en el ámbito de la asignatura de Educación Física: un estudio con alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria [Attitudes towards body expression in physical education: A study with students of compulsory secondary education]. Retos: Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deportes y Recreación, 41, 596-608. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i41.83296

Awally, A. F., Suherman, A., & Subarjah, H. (2023). The influence of teaching style and motivation level on increasing learning outcomes table tennis skills. Halaman Olahragan Santara, 6(1) (Online).

Bardorfer, A., & Dolenc, P. (2022). Teacher-student rapport as predictor of learning motivation within higher education: The self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Psychological & Educational Research, 30(2), 115–133.

Brown, L. M. (2021). The impact of student-centered learning through use of peer feedback in the dance technique classroom. Journal of Dance Education, 23(2), 144-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2021.1932911

Byra, M., Sanchez, B., & Wallhead, T. (2013). Behaviors of students and teachers in the command, practice, and inclusion styles of teaching: Instruction, feedback, and activity level. European Physical Education Review, 20(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X13495999

Colás, M.P., & Rebollo, M.A. (1993). Evaluación de programas. Una guía práctica [Program evaluation. A practical guide]. Seville: Kronos.

Campbell, D.T., & Stanley, J.C. (1963). Diseños experimentales y cuasi-experimentales en la investigación social [Experimental and quasi-experimental designs in social research]. Amorrortu.

Constantino, S., & Espada, M. (2021). Análisis de los canales de desarrollo e inteligencia emocional mediante la intervención de una unidad didáctica de Mindfulness y Biodanza en Educación Física para secundaria [Analysis of the channels of development and emotional intelligence through the intervention of a mindfulness and biodanza teaching unit in physical education for secondary school]. Retos: Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 40, 67-75. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v1i40.81921

Cothran, D. J., Kulinna, P. H., Banville, D., Choi, E., Amade-Escot, C., MacPhail, A., Macdonald, D., Richard, J.F.; Sarmento, P., & Kirk, D. (2005). A cross-cultural investigation of the use of teaching styles. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 76(2), 193-201. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2005.10599280

Cuellar-Moreno, M. (2016). Effects of the command and mixed styles on student learning in primary education. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 16(4), 1159-1168. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2016.04186

Cunliffe, D., Stopforth, M., & Rist, R. (2011). Teaching dance to children: should it continue to be done kinaesthetically? In European College of Sports Science: 16th Annual Congress 2011. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4475.0089

de las Heras-Fernández, R., Espada, M., & Cuellar, M. J. (2019). Percepciones de los/as estudiantes en los estilos de enseñanza comando y resolución de problemas en el aprendizaje del baile flamenco [Students’ perceptions of command teaching styles and problem solving in flamenco dance learning]. Revista Prisma Social, (25), 84-102. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/2601

de Las Heras-Fernández, R., Cuellar-Moreno, M. J., Espada, M., & Anguita, J. M. (2022). The influence of teaching styles on the emotions of university students in dance lessons according to sex. Research in Dance Education, 26(2), 182–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2022.2144197

Dolenc, P. (2022). Evaluating achievement motivation in physical education context: The use of the goal orientations in exercise measure. Journal of Psychological & Educational Research, 30(1), 85–98.

Dorantes-Nova, J. A., Hernández-Mosquera, J. S., & Tobón-Tobón, S. (2016). Juicio de expertos para la validación de un instrumento de medición del síndrome de burnout en la docencia [Expert judgment for the validation of an instrument to measure burnout syndrome in teaching]. Ra Ximhai, 12(6), 327-346. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B_QQ0W8TI5acM3k1bExzV2N3b3c/view?resourcekey=0-deaDsD0ApxQzivRGeJf0nw

Espada, M., Fernández, M., & Calero, J. C. (2021). Validación española del cuestionario experiencia y percepción de los estudiantes del espectro de estilos de enseñanza en Educación Física [Validation of the Spanish version of the Questionnaire on Physical Education Students’ Experience and Perceptions of the Spectrum of Teaching Styles]. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 13(2), 305-318. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/JSHR/article/view/89607

Gaviria-Cortés, D. F., & Castejón-Oliva, F. J. (2019). ¿Qué aprende el estudiantado de secundaria en la asignatura de educación física? [What do high school students learn in physical education?] Revista Electrónica Educare, 23(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.23-3.2

Jaakkola, T., & Watt, A. (2011). Finnish physical education teachers’ self-reported use and perceptions of Mosston and Ashworth’s teaching styles. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 30(3), 248-262. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.30.3.248

Kılıç, K. & Ince, M. L., (2023) Perceived use and value of reproductive, problem-solving, and athlete-initiated teaching by coaches and athletes. Frontiers Psychology, 14, 1167412. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1167412

Kolb, D. (1976). Learning style inventory. McBer and Company.

Kulinna, P. H., & Cothran, D. J. (2003). Physical education teachers’ self-reported use and perceptions of various teaching styles. Learning and Instruction, 13(6), 597-609. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(02)00044-0

Kyritsopoulos, D., Athanailidis, I., & Digelidis, N. (2023). Evaluation of the reciprocal teaching style in tennis. European Journal of Sport Sciences, 2(2), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejsport.2023.2.2.53

Lafuente, J. C. (2022). Valoración de los contenidos de Expresión Corporal por parte de los futuros maestros en la asignatura de Actividades Físicas Artístico-expresivas de la mención de Educación Física [Assessment of body expression content by future teachers in the course “Artistic-expressive physical activities” in the specialization in physical education]. Retos: Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 43, 205-214. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v43i0.87553

Laher, S., Fynn, A., & Kramer, S. (2019). Transforming research methods in the social sciences: Case studies from South Africa. Wits University Press.

Lopezosa, C., Codina, L., & Freixa, P. (2022). ATLAS.ti para entrevistas semiestructuradas: guía de uso para un análisis cualitativo eficaz [ATLAS.ti for semi-structured interviews: A user's guide for effective qualitative analysis]. https://repositori.upf.edu/bitstream/handle/10230/52848/Codina_atlas.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Mosston, M., & Ashworth, S. (1993). La enseñanza de la educación física: la reforma de los estilos de enseñanza [Teaching physical education: The reform of teaching styles]. Hispano Europea.

Mosston, M., & Ashworth, S. (2008). Teaching physical education. Spectrum Teaching and Learning Institute.

Nájera, R. J., Nuñez, O., Candia, R., López, S. J., Islas, S. A., & Guedea, J. C. (2020). ‘How is my teaching?’ Teaching styles among Mexican physical education teachers. Movimento, 26, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.99495

Nieto, S. (2010). Principios, métodos y técnicas esenciales para la investigación educativa [Essential principles, methods, and techniques for educational research]. Dykinson.

Pitsi, A., Digelidis, N., & Filippou, F. (2023). Effect of different teaching methods (reciprocal and shelf-check TS) on learning and performance of traditional Greek dance. Research in Dance Education, (online) 1–25.https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2023.2258814

Rakha, A. H. (2023). Application of 3D hologram technology combined with reciprocal style to learn some fundamental boxing skills. PLoS ONE, 18(5), e0286054. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286054

Real-Pérez, M., Sánchez-Oliva, D., & Padilla, C. (2021). Proyecto África “La Leyenda de Faro”: Efectos de una metodología basada en la gamificación sobre la motivación situacional respecto al contenido de expresión corporal en Educación Secundaria (Africa Project “La Leyenda de Faro”: Effects of a gamification-based methodology on situational motivation with respect to corporal expression content in secondary education]. Retos: Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 42, 567–574. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v42i0.86124

Requena, C. M., & Martín, A. M. (2015). Estudio de la convergencia entre perspectivas de enseñanza y estilos de aprendizaje en la danza académica [Study of the convergence between teaching perspectives and learning styles in academic dance]. Journal of Teaching Styles, 8(15), 222–255. https://doi.org/10.55777/rea.v8i15.1034

Ríos, K. M. (2019). La entrevista semi-estructurada y las fallas en la estructura. La revisión del método desde una psicología crítica y como una crítica a la psicología [The semi-structured interview and flaws in its structure. A review of the method from a perspective of critical psychology and as a critique of psychology]. Caleidoscopio-Revista Semestral de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 23(41), 65–91. https://doi.org/10.33064/41crscsh1203

Romanelli, F., Bird, E., & Ryan, M. (2009). Learning styles: A review of theory, application, and best practices. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 73(1), 1–5.

Romero-Barquero, C. E. (2015). Al compás de las clases de baile: una experiencia dentro del aula [To the beat of dance lessons: A classroom experience]. Revista Educación, 39(1), 21–49.

Rothmund, I. V. (2023). Student-centred learning and dance technique: BA students’ experiences of learning in contemporary dance. Research in Dance Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2023.2230135

Sánchez, M. C. (2015). La dicotomía cualitativo-cuantitativo: posibilidades de integración y diseños mixtos [The qualitative-quantitative dichotomy: Integration possibilities and mixed designs]. Campo Abierto, 1(1) 11–30. https://revista-campoabierto.unex.es/index.php/campoabierto/article/view/1679

Sicilia, A., & Delgado, M. A. (2002). Educación física y estilos de enseñanza: análisis de la participación del alumnado desde un modelo socio-cultural del conocimiento escolar [Physical education and teaching styles: Analysis of student participation from a socio-cultural model of school knowledge]. INDE.

Syrmpas, I., Papaioannou, A., Digelidis, N., Erturan, G., & Byra, M. (2020). Higher-order factors and measurement equivalence of the Spectrum of Teaching Styles’ Questionnaire across two cultures. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 40(2), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2019-0128

Torrents, C.; Ric, Á., & Hristovski, R. (2015). Creativity and emergence of specific dance movements using instructional constraints. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038706

Villard, M., Abad, M. T., Montávez, M., & Castillo, E. (2013). Percepciones del profesorado de Educación Física de Secundaria en Andalucía: metodología y expresión corporal [Perceptions of secondary school physical education teachers in Andalusia: Methodology and body expression]. Retos: Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, (24), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i24.34546

Yanık, M., Balcı, T., & Göktaş, Z. (2023). The congruence of teaching styles used by Turkish physical education teachers with national curriculum’ goals and learning outcomes. Eurasian Journal of Sport Sciences and Education, 5(2), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.47778/ejsse.1323148

Yudho, F. H. P., Dermawan, D. F., Julianti, R. R., Iqbal, R., Mahardhika, D. B., Dimyati, A., Nugroho, S., & Resita, C. (2023). The effect of motivation on increasing students’ cognitive ability through guided discovery learning. European Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 4(1), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejedu.2023.4.1.559

Zapatero, J. A. (2017). Beneficios de los estilos de enseñanza y las metodologías centradas en el alumno en Educación Física [Benefits of student-centered teaching styles and methodologies in physical education]. E-Balonmano. Com: Revista de Ciencias del Deporte, 13(3), 237–250. http://ojs.e-balonmano.com/index.php/revista/article/view/379/pdf

Zeng, H. Z. (2016). Differences between student teachers’ implementation and perceptions of teaching styles. Physical Educator, 73(2), 285. https://doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2016-V73-I2-6218