Application of Web 2.0 to Reduce Failure in English

How to cite: Pineda, K. A. & Jerónimo, R. (2024). Application of Web 2.0 to Reduce Failure in English. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 26, e05, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2024.26.e05.6038

Abstract

The purpose of the intervention was to reduce the failure rate in English with the help of a website built to support the learning experience. Action research was employed in a mixed-methods approach with an exploratory sequential design. Techniques such as documentary analysis, semistructured interviews, and participant observation were employed with 255 high schoolers. Findings revealed that the website, together with follow-up from the teacher-researchers, helped most students achieve a passing grade, empowered the learning experience, and enhanced communicative competence and linguistic awareness. Additionally, the website’s user-friendly nature and well-suited interface simplified the learning dynamic. Furthermore, according to website data, this digital space was also used in other settings with similar objectives. Even so, apathy remained a problem as some learners chose not to take part in the strategy and did not pass. We believe that the research contributes to the state of the art and generates knowledge, especially given the lack of research addressing failure in language education.

Keywords: educational innovation, linguistic research, educational sciences, foreign language

I. Introduction

Many educational projects have been carried out to foster innovation in different settings through the use of digital technology (Haleem et al., 2022), and rightfully so. Such has been the case with the application of mobile learning (Traxler, 2021), Web 2.0, and institutional platforms (Jurado & Martos, 2022).

Scholarship has found that most efforts have focused on change or transformation of praxis (Salas et al., 2021), which is deemed relevant and emphasized in all circumstances, whether improvement in the teaching-learning process is necessary or not (Vázquez & Ortíz, 2018). In this sense, we envisage a need for more research on how these technological resources can be used to reduce failure rates in foreign language learning (Díaz-Barajas & Ruiz-Olvera, 2018), as this is a nationwide problem (Savvides et al., 2021) faced regularly in educational settings (Murillo-García & Luna-Serrano, 2021).

It is this problem that prompted this study, which examines how technology serves as a powerful tool to combat failure rates. Many teenagers from two high schools in the Colegio de Bachilleres del Estado de Sinaloa system are low achievers or in the worst cases, fail their English course. Preliminary informal interviews suggest this is because learners are simply not interested in school or in the English language. Another possible reason is that they are unaware of what they need to do to pass the subject. Because of the failure rate, it came to our mind that a website created by the main researcher, Kristian A. Pineda, could be used to help students.

The object of study can be defined as the use of Web 2.0 to reduce failure rates in high school. Additionally, the following central question came to guide the research: How do high schoolers perceive the support provided by a website built on Wix.com to remediate low achievement in English? This question helped to determine the general purpose of the research, which was to reduce failure rates in English with the help of a website developed on the Wix.com platform (a Wix website) to support their learning experience.

Subsequently, we formulated a working hypothesis, or tentative answer. The research adopts a mostly qualitative approach that makes use of quantitative data analysis to strengthen our findings. The use of Web 2.0 can help enhance learners’ grades in English as these digital resources, developed especially for their learning level, offer an enjoyable way for adolescents to learn and practice the language.

1.1 Aspects related to failure in English classes

Despite the wealth of resources available on Web 2.0 and mobile devices, very few options offer quality instruction in English. This is also the case internationally; the current education system seems to hinder learners from acquiring the necessary skills to cope in a foreign language. In this sense, the predominant educational model educates adolescents and adults to be submissive, rather than critical thinkers who undertake initiatives to break the status quo (De la Cruz, 2022). This may be associated with the negative attitudes some students display towards English classes, which may in turn lead to failure.

Some of the most common causes of failure in English classes are negative attitudes towards the subject or the use of traditional teaching methods. In this sense, national and international research has sought to understand the factors that contribute to this problem. For instance, experts have revealed that teachers, emotional issues, English labs, and inappropriate study habits all bear a greater relation to learners’ failure than motivation, friends, and family matters. It has also been suggested that, especially in college courses, the foreign language curriculum ought to reflect a connection to students’ majors so that undergraduates can make a meaningful association between the target language and their professional education (Umar-Sa’ad & Usman, 2014).

Similarly, in Mexico, scholars such as Sánchez-Aguilar et al. (2017) have also conducted research into higher education. Their findings echo previous studies (Umar-Sa’ad & Usman, 2014), suggesting that low achievement correlates with teaching methodologies that fail to inspire students to engage more deeply with foreign language acquisition and syllabus content. In addition, the students’ need for more learning strategies and a lack of previous knowledge about the subject were also discovered to be related to failure (Díaz & Ruiz, 2018).

Furthermore, scholarship has revealed that failure is strongly related to dropout. This phenomenon has been described by various experts, who see it as a serious issue that affects the quality of education (Torres-Zapata et al., 2020). Also, it has been found that the more subjects learners fail, the greater their chances of dropping out. Similarly, poor outcomes in learning English have long been studied, and affective aspects have been found to be crucial for effective language acquisition (Krashen, 1982).

On the other hand, there are occasions where teachers seek an active or proactive role in the education process, but they meet with failure due to the learners’ difficulties (Prihantoro & Hermawan, 2021). Some impediments may be associated with poor metacognition, low self-efficacy, or a lack of learning strategies (DiFrancesca et al., 2016). Additionally, other studies have demonstrated that communication is paramount in language education, and it is deemed crucial that English teachers build the kind of rapport considered necessary to support learning of the foreign language (Meléndez-Machorro et al., 2022).

1.2 Digital technology applied to foreign language learning

The internet is revolutionizing communication in different settings, including education. In that sense, applying Web 2.0 opens the door for teaching praxis and the transformation of the learning environment into one that is centered on the student, as many resources can be adapted. Nevertheless, with these simultaneous changes, teachers, learners, and other stakeholders need to acquire the basic abilities to manage online tools (Martínez-Pérez, 2021).

Indeed, digital technology has played a significant role in school settings, and foreign language learning is no exception. Research shows a positive correlation between academic motivation and educational technology, especially with mobile devices or computers. Additionally, promoting student motivation with technology can encourage the use of technology and foster student inclusion in different communities, familiarity with other cultures, and most importantly, interaction with other users of a foreign language (Wei, 2022).

In that vein, other work has found that using Web 2.0 may enhance English students’ reading skills, while also supporting effective communication (Bensalem, 2000). In addition, one advantage of educational technology is that it could reduce anxiety-related difficulties. Moreover, it can also address differences between learners, such as preferred learning styles, which might sometimes hinder learning in face-to-face instruction.

Other studies have made it evident that Web 2.0 now plays a more dominant role in the English learning process. The internet offers platforms like Facebook, blogs, and others specifically geared to education. A study carried out by Stefancik and Stradiotová (2020), for instance, proposed podcasting to motivate learners to enhance their language skills. Their research deduced that podcasts used to support traditional classes can help language learners significantly increase their listening skills. Kazazoğlu and Bilir (2021) offer another example in a study on the advantages of computer-assisted writing, where it was hypothesized that computer-assisted writing plays a positive role for Generation Z (Gen Z). The goal here was to uncover the learner’s overall reflections on writing in the foreign language through Storybird Web 2.0, which was found to be an effective tool.

The internet and mobile apps support English learning; however, in some educational settings, learners appear to show some reluctance towards learning activities that involve speaking or listening. Furthermore, it has been recommended that these technological resources be applied in conjunction with face-to-face instruction to foster a more active and friendly environment that meets the expectations of the students, teachers, and institution (Mohamed, 2021).

These previous studies lend weight to the view that it has become necessary to use digital resources to reduce school failure rates. Moreover, scholarship has clearly shown that, especially in English, more software is being developed and used to facilitate language acquisition and learning. Furthermore, this use of software has also been discussed in other disciplines as it is more student-centered (Nawaila et al., 2020).

The contributions made by these researchers are critical for this research since many of the learners in this study face these same issues. Moreover, the online literature review revealed some successful intervention processes undertaken to remediate these problems. This backdrop justifies, from an empirical but also a critical standpoint, this action research in the two Mexican educational settings that constitute the focus of this paper.

II. Methodology

Action research was conducted with a mixed-methods approach, QUAL-quan, following a conversion design. This type of inquiry can be classified as exploratory sequential (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2018) since it places emphasis on the qualitative research procedure, while the quantitative phase only converts data into numbers, providing deeper insight into the data (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). Epistemological canons state that in a critical approach in education science, scholars must seek to generate substantive theories grounded in participants’ practices and contexts; moreover, positivist or objectivist approaches are strongly discouraged (Carr & Kemmis, 1986). Nonetheless, in a pragmatic endeavor, we decided to go further by employing quantitative analysis to reinforce interpretations and rigor in our research without undermining the emancipatory stance.

Action research reemerged during the twentieth century with contributions from progressives, who sought to enlighten and call upon the oppressed to take action to solve social issues (Efrat-Efron & Ravid, 2013). For this reason, we take the research beyond its traditional limits by employing a mixed-methods design to remediate the problem of student failure in English.

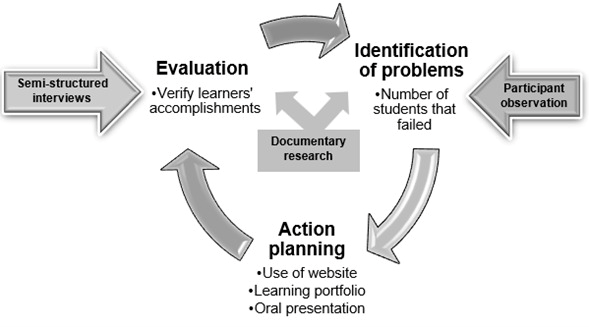

Various contributions have been made to action research, and experts adapt designs to their beliefs, possibilities, and experiences (Cohen et al., 2018), which is also the case for this intervention. The study design included the phases of problem identification, action planning, and evaluation of results, all repeated in two cycles from February to December 2022 (Figure 1).

Techniques and instruments. One key instrument was the website built by the main researcher, Kristian A. Pineda, on the Wix.com platform (see Pineda, 2021). In short, the website was created with different aspects in mind. The purpose of the site, which is to provide English learning support, is established on the homepage. For ease of navigation and organization, the homepage provides access buttons and a search bar; the layout is user-friendly and elements are ordered from basic to advanced level, according to the institutional syllabus. The site offers other features, including video clips and grammar, reading, writing, and speaking practice opportunities (see more details at https://kristiancb.wixsite.com/lekcb).

Experts have proposed guidelines for collecting data in action research (Stringer, 2007). With that in mind, documentary research, semistructured interviews, and participant observation were conducted throughout the intervention. In this study, the main sources of data were rubrics, portfolios, and observation logs. Specifically, a language content portfolio and an oral presentation rubric, divided into unsatisfactory, satisfactory, and excellent levels, were utilized. The rubric was validated through a qualitative approach, as detailed in previous research (Pineda, 2021).

Participants. It is difficult to keep updated school records as some teenagers change schools often and others only formally enroll at the very end of the semester, an aspect that is out of the researchers’ hands. With this in mind, purposive criterion sampling was employed (Cohen et al., 2018). Inclusion criteria included adolescents having failed a term in English, a low grade point average, or an irregular attendance record in class. All students can be classified below a beginner’s level since they had little knowledge of the language, with poor grammar, vocabulary, and speaking, listening, writing, and reading skills. In total, 255 learners took part in the study: 130 males and 125 females, aged 15 to 17 years. The participants were from 10 preestablished groups (Table 1).

| Group | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| Group 2 | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| Group 3 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Group 4 | 15 | 15 | 30 |

| Group 5 | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| Group 6 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Group 7 | 15 | 10 | 25 |

| Group 8 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Group 9 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Group 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

Procedure. From February to April 2022, participant observation allowed the main researcher, Kristian A. Pineda, to detect adolescents at risk of failing English. The school record system provided information that helped rapidly identify these risk factors. We devised a strategic plan aimed at enabling students to improve their grade while providing them with the opportunity to work on an assignment that would offer a positive experience in the foreign language class. The plan consisted of 1) identifying learners who have failed, 2) presenting the website and the learning opportunities it provides (Pineda, 2022), and 3) evaluating learning.

Accordingly, the website was presented to the 255 students for them to interact with the videos, learning quizzes, and integrative activities. For the oral presentations, learners were provided a rubric that included the grading criteria. The instrument was considered valid as it had been used previously in other interventions to evaluate speaking activities (Pineda, 2021). Students were asked to study the contents of English 1 for the first semester and English 3 for the third semester, which are aligned to the institutional syllabus, and it was suggested they went over the videos and did the practice activities on the webpage to help them succeed in their oral presentations.

The next step, from May to June 2022, involved the documentary analysis of the speaking evaluation instrument, plus an interview with 20 teenagers identified as stakeholders: 10 males and 10 females. This approach is grounded in the insights of experts in action research (Stringer, 2007), who assert that stakeholders may include individuals involved in the scenario who play representative roles. In this context, the selected students are considered stakeholders. Information was distilled using constructivist grounded theory techniques such as open, focused, and axial coding (Charmaz, 2006). We carried out this analysis with a view to subsequently comparing findings and reaching a consensus on interpretations.

During the second action research cycle, the steps were repeated to reach those students who met the inclusion criteria but did not achieve a passing grade in the first phase. Again, from September to October 2022, adolescents who had failed were identified and contacted through various means, including in-school face-to-face discussions and social networks like Facebook or WhatsApp. Once more, the website was presented to the 123 learners: 69 male and 54 female. Just like in the previous step, the purpose was to provide access to videos, learning quizzes, and integrative activities created by the main researcher, Kristian A. Pineda. The difference in this cycle was that teenagers were asked to develop a portfolio of content learned and available on the internet site, given that they were struggling with the oral presentation.

From November to December 2022, both documentary analysis and a semi-structured interview with 20 learners (10 male and 10 female) were conducted to assess the impact of the intervention. In this sense, the constructivist grounded theory techniques were useful for coding and categorizing data and establishing relationships between categories. The documentary analysis consisted in analyzing the information presented in the portfolios to see if students achieved the academic expectations (Table 2).

| Period | Research technique | Participants | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February-April 2022 | Participant observation | 255 | 130 | 125 |

| Speaking evaluation | 255 | 130 | 125 | |

| May-June 2022 | Documentary analysis | 255 | 130 | 125 |

| Semistructured interview | 20 | 10 | 10 | |

| Portfolio | 50 | 53 | 103 | |

| September-October 2022 | Participant observation | 255 | 130 | 125 |

| November-December 2022 | Documentary analysis | 255 | 130 | 125 |

| Semistructured interview | 20 | 10 | 10 | |

| Nota: It was possible to apply most techniques with the whole sample. | ||||

III. Resultados

Findings are presented by first describing the substantive hypothesis discovered due to the intervention as well as the relationship between categories. After that, the categories that build the theory are explained, with some of the answers and documentary evidence gathered throughout the research. Lastly, descriptive statistics are employed to provide a deeper analysis of the data.

Substantive hypothesis. Using Web 2.0 to reduce failure rates in English has a positive impact on low-achieving adolescents’ grades. In this vein, the website enriched the educational experience as the assessment and constant monitoring encouraged the development of communicative competence and linguistic awareness. Additionally, the website’s user-friendly nature simplified interaction and formative activities for students as the interface and resources were well suited to their academic needs. Furthermore, the website surpassed its original intent, as data provided by the Wix.com platform showed that it was being used in other contexts for similar purposes.

3.1 Qualitative analysis

Communicative competence assessment. Although there were a few difficulties, most learners gave successful oral presentations. In the interviews, students were asked how they felt after receiving support from the website. They acknowledged that teaming up with a classmate and analyzing the rubric provided was crucial: “...at first, I did not understand how to use the rubric, but as I read it over and over again, I guess I got familiar with the dynamics” (S14/May 19, 2022). Regarding collaborative work, another teenager stated, “...I used several videos to practice my pronunciation and sentence construction. I mean, you pretty much had everything in there. Plus, my partner helped me with some of the words during our conversation.”

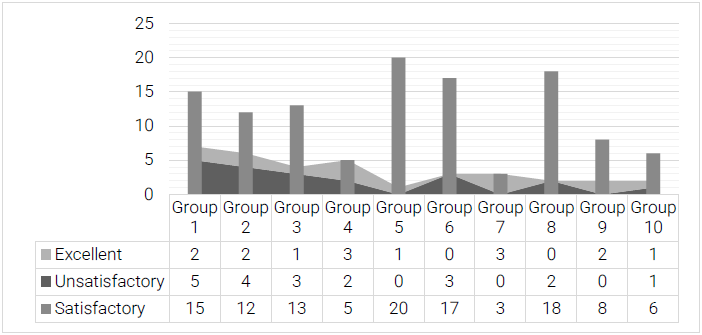

The rubric was a valuable document that provided a clear view of each student’s performance level. While we intended to evaluate all 255 high schoolers through documentary analysis, it was only possible to assess 152 due to various factors, including student attitudes. Only 117 achieved a satisfactory level, scoring between 6.0-7.9, which was perceived as acceptable, taking into account that these are low achievers. A few others, 15, achieved scores ranked as excellent, 8.0 or above, and 20 received inadequate grades of 5.0 or below. Most students struggled with fluency and accuracy, but achieved a passing grade since other elements, such as organization and creativity, were evaluated as well.

During the presentations, it was observed that some learners were very motivated to present their final product, while the remaining 103 were displeased at being required to speak in front of somebody else, a characteristic we codified as anxiety. This issue was discussed with students so that everybody would respect their classmates since they were all being evaluated under the same grading criteria, but despite this, they still did not take the speaking evaluation. Fortunately, most learners achieved a passing score. For those who did not, an alternative strategy became necessary, which will be discussed below.

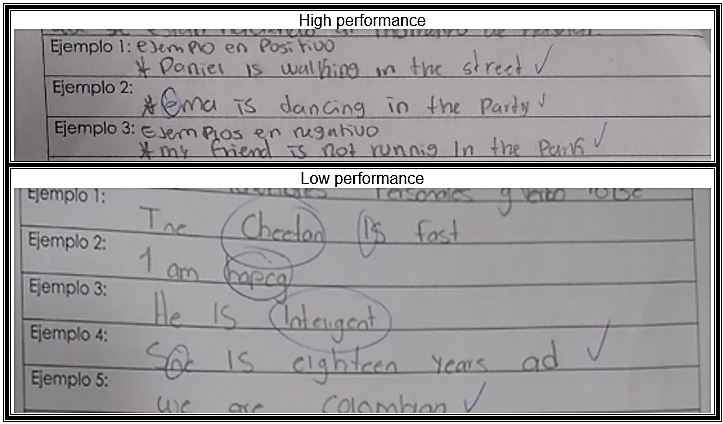

Linguistic awareness. In the second cycle, from September to October 2022, high schoolers were asked to create a portfolio that contained the topics presented in the videos on the website. In this case, the portfolio analysis showed how they improved their understanding of the grammatical items as they produced sentences from the explanations in the videos (Figure 2). This was enough evidence for the remaining 123 students to be awarded a passing grade, average 6.0, and to confirm that they had attained the minimum level of linguistic knowledge.

Learners dedicated more time and took greater care in completing the assignment. Most of the portfolios turned in were well organized and showed a touch of creativity since some students were able to build expressions in English based on the examples seen in the videos, reflecting a constructivist perspective. In a behaviorist learning style, the low performers copied the examples exactly the way they were presented in the video clips.

User-friendly nature of the website. During the interviews, learners were asked how difficult it was for them to navigate the website, considering they had been given a brief introduction to the site with the aim of making navigation easier. Their answers were all interpreted as indicative of a positive experience since they had no difficulty finding the topics or using the online quizzes to practice elements of the language: “I actually found it pretty easy to find whatever I needed, especially with the search bar at the top of the website; I guess that is the best shortcut anyone can take” (S4/May 18, 2022). Another teenager added a similar comment: “Well, it was very intuitive. I normally visit your web page from my cell phone… in my opinion, this was more practical than doing it from a computer” (S11/June 01, 2022).

Another element that made the website more user-friendly was the way online quizzes were positioned and designed. Every section provided an opportunity for adolescents to practice their grammar and reading skills based on the topics covered throughout the learning blocks (Figure 3). One of the learners interviewed made the following comment: “What I like about the exercises is that I can try them as many times as I want. This is an excellent way to verify my answers. Some reading exercises are kind of interesting too, others not that much” (S19/December 01, 2022).

Seeing these exercises as an opportunity to complement the face-to-face learning experience, learners responded very well to this academic initiative. One drawback was that because students could answer the quizzes at any time, the main researcher, Kristian A. Pineda, was receiving messages – notifications of completed tasks or questions – all day long. The second researcher, Rubén Jerónimo Yedra, assisted in this sense by providing guidance to students.

Empowering the learning experience. Participant observation and documentary analysis facilitated critical monitoring that ultimately confirmed that the intervention improved the learning experience. This could be determined from the students’ portfolios and successful oral presentations. Also, throughout the interviews, they were asked to provide their perspective on the effectiveness of the strategies; all students agreed that the tactic was different from traditional approaches to dealing with failing learners: “…normally, I take an exam if I fail a class. In my opinion, the way we did it this time is better and more interesting” (S18/November 03, 2022).

In addition, Kristian A. Pineda also provided support to low achievers whenever they had questions related to the oral presentation or portfolio. One student commented: “…I had some problems when I was doing the portfolio. The good thing is that I was able to watch the videos or ask you, teacher, any questions I had” (S11/November 15, 2022).

Apathy. We decided to create this category because some learners did not meet the inclusion criteria and therefore were not included in the research process, while others did not meet the academic requirements of the assignments. In this respect, the intervention was not a complete success, as some students did not take advantage of these opportunities to remediate their academic standing. During the interviews, high schoolers were asked if they knew of any reason why their classmates neglected to take this chance. Their responses pointed to a lack of interest in education: “…I think that they simply do not care” (S9/December 2, 2022).

Another high schooler added, “…From what I know, José has other interests, he is even going to drop out of school, and his parents are not really worried about him since they have other problems” (S12/December 10, 2022). Unfortunately, there was no more time to develop an additional academic strategy to provide follow-up for these students, and they were referred to the counseling department.

3.1 Quantitative analysis

We proceeded to transform the data, seeking to provide deeper insight. With the assistance of the second researcher, Rubén Jerónimo Yedra, qualitative information was converted into quantitative values, an exhausting task considering the amount of data gathered throughout the year. The data relate to the documents and techniques used during the intervention, such as the speaking rubrics, portfolios, participant observation log, and semistructured interviews.

In this sense, descriptive statistics were employed by Rubén Jerónimo Yedra to include the data from the whole sample. In terms of communicative competence and linguistic awareness, as assessed in the rubrics, 117 students (45.88%) achieved a satisfactory score and 15 (5.88%) achieved an excellent grade, while 20 (7.84%) received scores that were still unsatisfactory. This meant that 132 of the low achievers (51.76%; 61 male and 71 female) passed the English course thanks to the first cycle of the intervention (Figure 4).

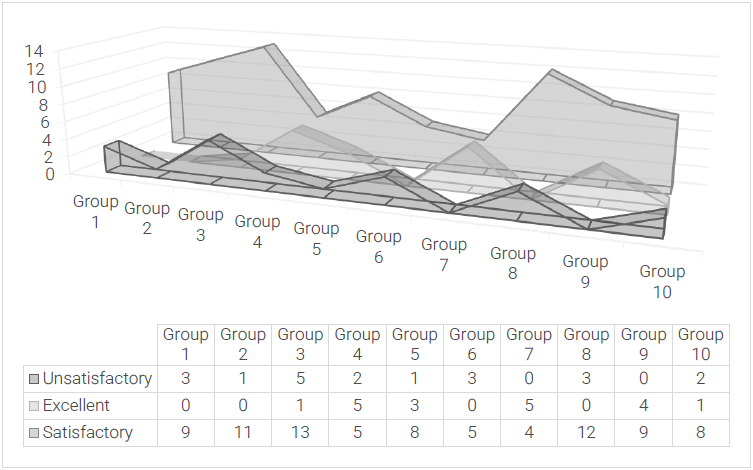

On the other hand, the following bar chart shows the number of students who passed the subject thanks to the portfolio they built using the web page during the second action research cycle. In this case, the grading criteria were adjusted to evaluate documentary evidence, maintaining the same three-level grading scale. In that respect, 20 students (7.84%) received an unsatisfactory score, 19 (7.45%) achieved an excellent score, and 84 (32.94%) were awarded a satisfactory grade. This meant that 103 high schoolers (40.39%) passed the subject in the second phase (Figure 5).

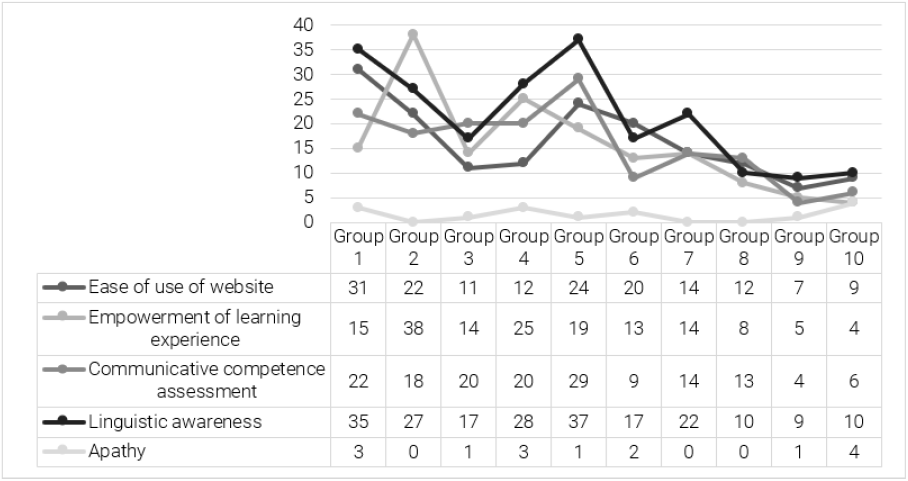

Additionally, the qualitative categories were defined based on their frequency across all the responses given in interviews, documentary analysis, and participant observation records. The category linguistic awareness occurs most frequently among learners, but this does not necessarily imply that the other categories had a lesser impact on the educational experience students gained from the website, as the groups with a lower frequency tended to have a smaller population of students (Figure 6). Thus, the distribution of responses across categories might not accurately reflect the impact of each category on the educational experience because the groups with lower frequencies (i.e., fewer students) could skew the perception of the overall impact. This is because a smaller number of students might not fully represent the significance or impact of certain categories, even if they occur less frequently. Therefore, the conclusion drawn from the frequency of categories across groups should be interpreted with caution, especially considering the varying sizes of the student populations in each group.

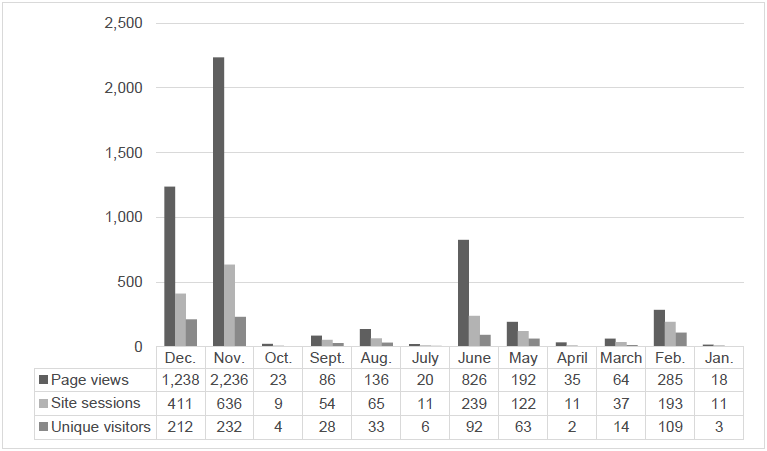

On the other hand, various features offered by the Wix.com platform enabled continuous monitoring to conduct more in-depth participant observation and documentary analysis. The platform provides reports to track traffic on the website, which can be calculated over a period of time. The chart below shows the traffic on the website Learn English with Kris (available at https://kristiancb.wixsite.com/lekcb) over 365 days (Figure 7). Likewise, the data indicates both widespread use and cases of individual access, demonstrating that the website serves not only as a resource for learners experiencing difficulties but also as a general aid for learning English, as has been the case since its inception (Pineda, 2021).

The Wix.com software also gives specific information about the number of visitors per city. This showed Kristian A. Pineda that these digital resources are having a local and national impact in many cities in Mexico and have begun to reach international users, from cities like Hayward in California, USA, and Lausanne in Switzerland (Figure 8).

IV. Discussion and conclusions

Some learners did not achieve a passing grade despite the efforts made and the resources available for them to accomplish the oral presentation or the portfolio. However, this does not mean that the strategy was a total failure. The statistical information clearly shows that the majority of students in the sample met the requirements, although some continued to perform very poorly and were unable to remediate their failing grades, either because they did not complete any of the assignments or did not present themselves to enable further examination of their situation.

In applied linguistics, some studies indicate that failure is also caused by disinterest in the course or a lack of learner autonomy (Marín et al., 2014). In keeping with this previous research, some adolescents in our study also showed strong disinterest in the subject. To address the issue of lack of autonomy, we assume that using the website will, to some extent, promote independence in students as they become more comfortable searching for information in cyberspace.

Empirical evidence from research reveals several possible causes of failure. For instance, teenagers may lack learning goals or resources, or they may be facing dysfunctional family issues that undermine their motivation to perform well in school. Furthermore, self-concept plays a crucial role in adolescents’ performance in high school, as does friendship, which has been found to be a particularly fundamental factor that correlates with learner achievement (Díaz & Ruiz, 2018).

The sample may introduce another source of bias, given that the groups lacked homogeneity in their quantitative characteristics. Nevertheless, the endeavor can be considered viable and pertinent since purposive sampling was carried out not with a view to achieving uniformity but in response to a situational need that was merely educational. In other words, the aim was not to be strict in terms of objectivity, instrumentation, linearity, or standardization; instead, the research sought to solve a severe problem – student failure – from a critical educational science perspective that is emancipatory in its intent, one of the main characteristics of action research (Carr & Kemmis, 1986).

As brilliant as digital technology may be, it has in many cases proved disadvantageous in education. Scholarship has clearly shown that technology can have an adverse impact on education. For instance, if learners do not receive proper instruction, it may end up worsening their reading and writing abilities. Additionally, it has been reported to diminish humanistic interaction, promoting isolation in educational environments (Alhumaid, 2019). However, this intervention could be an example of how both elements, digital technology and human interaction, can work together, but it takes a great deal of effort and passion from educators to carefully plan the implementation of these wonderful resources. This is especially important given that a lack of language laboratories and inadequate instructional media can influence learner achievement (Umar-Sa’ad & Usman, 2014).

From an educational and linguistic research standpoint, research carried out by Sánchez-Aguilar et al. (2017) found that learners acknowledged their inability to come up with strategies for successful language learning. In this sense, we believed that perhaps many of the students in our intervention had similar problems. We believe that creating portfolios helped increase not only their language awareness but also their learning skills in general. In fact, a few studies have reported that this resource fosters self-monitoring, autonomy, and a responsible attitude on the part of learners (Syamsul et al., 2021).

At a deeper level, and from a critical standpoint as action researchers, the connectivist learning theory asserts itself in the fact that the internet has created openings for students to interact in a virtual space to gain access to many educational resources available internationally. In this respect, the network is not just a means to share, consult, or disseminate knowledge, but more importantly, it contributes to the progress of society. Indeed, education in particular has been one key objective of digital resources (Nawaila et al., 2020).

We were also able to identify how learners used the website, with learning strategies that demonstrated both constructivist and behaviorist approaches. Constructivist learners were more creative and original in their portfolio. In this vein, as expounded by Papert, technology should not be applied to foster a learning environment that is a copy of reality, but as a facilitator to create and recreate knowledge in a constructionist fashion (Gros-Salvat, 2001). On the other hand, evidence submitted by high schoolers who implicitly took a behaviorist stance was less creative, that is, the language expressions they presented in their portfolios or oral presentations were very similar to the language used by Kristian A. Pineda to explain the various topics. In this respect, we took into consideration the purpose of the intervention, which was to reduce the failure rate in English. This explains why we considered whether it was pertinent to pass all such students or only those who met the minimum criteria; the latter option seemed most appropriate.

It can be concluded that the study’s overall goal of reducing the failure rate with the use of Web 2.0 was met. Using the website strengthened students’ educational experience since the educator’s assessment and constant monitoring from both researchers boosted communicative competence and linguistic awareness. Additionally, the website’s user-friendly nature and well-suited interface and resources facilitated learner interaction and learning dynamics. Moreover, the website surpassed its original purpose as Wix.com data showed how it was also being employed in other contexts.

Nevertheless, apathy and lack of interest in education remained a problem even with this innovative intervention; some students did not achieve a passing grade despite these opportunities. This raises the following possible lines of research: What motivational tactics can be employed with low achievers who are not concerned with their personal growth? Or how can unmotivated high schoolers become more engaged in their education? More questions can be drawn from this or other studies, but rather than coming up with lines of inquiry, educational researchers should seek to implement actions or projects that entail synergy between major stakeholders to achieve a greater impact on educational issues.

Furthermore, the results of this study indicate that action research still offers a way to achieve innovation in practice. Nonetheless, such a transformation must take into account the realities of each context and all those involved, since everybody affected by an issue should play some role in making democratic change possible.

Contribution of each author:

Kristian Armando Pineda Castillo: Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing-original draft.

Rubén Jerónimo Yedra: Supervision; Investigation; Validation; Visaulization; Writing-reviewing & editing.

Declaration of no conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Source of funding:

This work received no funding.

Referencias

Alhumaid, K. (2019). Four ways technology has negatively changed education. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 9(4), 10–20. https://www.richtmann.org/journal/index.php/jesr/article/view/10526

Bensalem, E. (2020). Foreign language reading anxiety in the Saudi tertiary EFL context. Reading in a Foreign Language, 32(2), 65-82. https://nflrc.hawaii.edu/rfl/item/442

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Falmer.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE Publications.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano-Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

De la Cruz, G. (2022). Política educativa y equidad: Desafíos en el México contemporáneo [Education policy and equity: Challenges in contemporary Mexico]. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 52(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.48102/rlee.2022.52.1.468

Díaz, D., & Ruiz, A. (2018). Reprobación escolar en el nivel medio superior y su relación con el autoconcepto en la adolescencia [Failure in upper secondary education and its relation to self-concept in adolescence]. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 48(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.48102/rlee.2018.48.2.49

DiFrancesca, D., Nietfeld, J. L., & Cao, L. (2016). A comparison of high and low achieving students on self-regulated learning variables. Learning and Individual Differences, 45, 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.11.010

Efrat-Efron, S., & Ravid, R. (2013). Action research in education: A practical guide. The Guilford Press.

Gros-Salvat, B. (2001). Burrhus Frederic Skinner y la tecnología en la enseñanza [Burrhus Frederic Skinner and technology in teaching]. In J. Trilla-Bernet (Coord.), El legado pedagógico del siglo XX para la escuela del siglo XXI (pp. 229-248). Graó.

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Qadri, M. A., & Suman, R. (2022). Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable Operations and Computers, 3, 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susoc.2022.05.004

Jurado, E. W., & Martos, F. (2022). Diseño de un sitio web de aprendizaje de inglés mediante el modelo ADDIE [Designing an English learning website using the ADDIE model]. Apertura, 14(1), 148–163. https://doi.org/10.32870/Ap.v14n1.2132

Kazazoğlu, S., & Bilir, S. (2021). Digital storytelling in L2 writing: The effectiveness of “Storybird Web 2.0 Tool”. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 20(2), 44-50. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1304892

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press Inc.

Marín, C. I., Librado, E., & Alarcón, M. E. (2014). Estudiantes universitarios en situación de examen de última oportunidad de Inglés I [University students and the last-chance exam in English I]. Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.15517/aie.v15i1.17589

Martínez-Pérez, M. G. (2021). Plataformas Web 2.0 para la producción del idioma inglés [Web 2.0 platforms for English production]. Con-Ciencia Boletín Científico de la Escuela Preparatoria No. 3, 8(16), 42-46. https://repository.uaeh.edu.mx/revistas/index.php/prepa3/article/view/7337

Meléndez-Machorro, I. E., Valencia-Cruz, K. G., Román-Ortiz, B., & González-Pérez, M. (2022). Analysis of the low level of achievement in the English subject of the Universidad Tecnológica de Tecamachalco. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 6(6), 5300–5310. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v6i6.3811

Mohamed, O. I. (2021). The effectiveness of Internet and mobile applications in English language learning for health sciences’ students in a university in the United Arab Emirates. Arab World English Journal, 12(1), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol12no1.13

Murillo-García, O. L., & Luna-Serrano, E. (2021). El contexto académico de estudiantes universitarios en condición de rezago por reprobación [The academic context of failing college students]. Revista Iberoamericana de Educacion Superior, 12(33), 58–75. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2021.33.858

Nawaila, M. B., Kanbul, S., & Alhamroni, R. (2020). Technology and English language teaching and learning: A content analysis. Journal of Learning and Teaching in Digital Age, 5(1), 16–23. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/joltida/issue/55477/760130

Pineda, K. A. (2021). Collaborative oral presentations as a strategy to evaluate English in Mexican high schoolers. Ciex Journal, (13), 19–30. https://journal.ciex.edu.mx/index.php/cJ/article/view/128

Pineda, K. A. (2022). Innovation through Web 2.0 to support English language learning. Sinéctica, (59), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.31391/s2007-7033(2022)0059-005

Prihantoro, A., & Hermawan, T. (2021). Success and failure of English as a foreign language lecturer in applying the assessment as learning in higher education. International Journal of Educational Spectrum, 3(2), 131-149. https://doi.org/10.47806/ijesacademic.896661

Salas, F., González, E. O., & Estévez, E. H. (2021). Microlearning: Innovaciones instruccionales en el escenario de la educación virtual [Microlearning: Instructional innovations in virtual education]. IE Revista de Investigación Educativa de la REDIECH, 12, e1262, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.33010/ie_rie_rediech.v12i0.1262

Sánchez-Aguilar, N., De Santiago-Badillo, B. S., & Jöns, S. (2017). Factores relacionados con la reprobación en Inglés en educación superior [Factors related to failure in English courses in higher education]. Conciencia Tecnológica, (54).

Savvides, N., Milhano, S., Mangas, C., Freire, C., & Lopes, S. (2021). ‘Failures’ in a failing education system: Comparing structural and institutional risk factors to early leaving in England and Portugal. Journal of Education and Work, 34(7–8), 789–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.2002831

Stefancik, R., & Stradiotová, E. (2020). Using Web 2.0 tool podcast in teaching foreign languages. Advanced Education, 7(14), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.20535/2410-8286.198209

Stringer, E. T. (2007). Action research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Syamsul, A., Abdullah, F., Siti Fatimah, A., & Nurul Hidayati, A. (2021). Portfolio-based assessment in English language learning: Highlighting the students’ perceptions. J-SHMIC: Journal of English for Academic, 8(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.25299/jshmic.2021.vol8(1).6327

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. SAGE Publications.

Torres-Zapata, Á. E., Rivera, J., Flores, P., García, M. del P., & Castillo, D. A. (2020). Reprobación, síntoma de deserción escolar en licenciatura en Nutrición de la Universidad Autónoma del Carmen [Failure, a symptom of dropout from the bachelor’s degree in nutrition at Universidad Autónoma del Carmen]. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 10(20). https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v10i20.602

Traxler, J. (2021). A critical review of mobile learning: Phoenix, fossil, zombie or …? Education Sciences, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090525

Umar-Sa’ad, T., & Usman, R. (2014). The causes of poor performance in English language among senior secondary school students in Dutse metropolis of Jigawa State, Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education, 4(5), 41-47.

Vázquez, J. C., & Ortíz, V. (2018). Innovación educativa como elemento de la doble responsabilidad social de las universidades [Educational innovation as an element of the dual social responsibility of universities]. IE Revista de Investigación Educativa de la REDIECH, 9(17), 133-144. https://doi.org/10.33010/ie_rie_rediech.v9i17.157

Wei, Y. (2022). Toward technology-based education and English as a foreign language motivation: A review of literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 870540. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.870540