Expectation and Academic Readiness Profiles in Higher Technical Education

How to cite: Castro, N., Suárez-Cretton, X., & Pareja, N. (2025). Expectation and academic readiness profiles in higher technical education. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 27, e02, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2025.27.02.5891

Abstract

Technical and vocational education and training is an important branch of education, pursued by increasing numbers of young people, and information in this regard is crucial. This research aims to determine student entry profiles based on their initial expectations and skills. A total of 183 newly admitted students of technical degrees at a public university responded to two scales used to measure academic expectations and readiness. This non-experimental, cross-sectional, descriptive research employs cluster analysis to identify four groups with high levels of academic expectations and readiness, but the findings show that effective communication and emotion modulation skills are weaker, as are student participation expectations.

Keywords: technical education, access to education, college students

I. Introduction

Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is aimed at developing skills and abilities for work and has existed in Latin America since 1940. In the context of the 2030 Agenda, in September 2015, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) secured the approval and commitment of 193 countries to guarantee inclusive, equitable, and high-quality education that promotes lifelong learning opportunities for all. In this sense, TVET is acknowledged as an important factor in developing the structure and competitivity of countries’ productive sectors and is delivered in a wide variety of ways across different countries in formal and non-formal systems, through programs directed by ministries of education and with participation from business and worker organizations. This form of education can be found at secondary, tertiary, and university levels, and one of the many challenges it poses is how to facilitate the transition from one level of education to the next (Siteal Unesco, 2019).

At the university level, academic expectations play an important role in students’ academic success. These expectations can be understood to mean the beliefs, motivations, and feelings associated with higher education by students (Soares et al., 2014). Academic expectations include engagement expectations, that is, expectations relating to what students expect to do or engage in, and which are associated with students’ behavioral engagement, academic success, and satisfaction (Almeida et al., 2003). Similarly, critical factors for TVET student satisfaction include perceived service quality, learning outcomes, employability, image, and value (de Oliveira et al., 2020). In addition, TVET students’ aspirations and career paths are affected by the connections between education and work and by how well their education aligns with the demands of the productive sector, thus enabling employment opportunities (Valdebenito & Sepúlveda, 2021). This can impact their satisfaction and learning, as one factor that influences TVET students’ learning and achievement is the interest they have or acquire in their subjects (Ismail et al., 2019), whereas a lack of expectations or goals, together with ignorance of or a failure to appreciate one’s own capabilities, can become limitations to learning (Sevilla-Santo et al., 2021).

Separately, research on TVET has found that the development of generic skills in students in technical degrees in higher education depends in part on students’ skills upon entry (Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019). The skills students bring with them when entering the program facilitate their adjustment to the university environment; this includes their ability to organize resources, generate appropriate strategies to achieve their goals, and anticipate risks analytically, in addition to their self-efficacy and self-determination. Conde et al. (2017) found that students’ planning skills predicted their academic expectations. Furthermore, on account of the shorter duration of technical degree programs compared to traditional higher education, which may result in very little time to develop generic skills, it is all the more important to evaluate these skills to include them in a student entry profile.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution requires a combination of technical and soft skills in the workforce (Saari et al., 2021). Research on TVET (Mahfud et al., 2017) has stressed the importance of soft skills such as communication, courtesy, honesty, responsibility, cooperation, discipline, a focus on getting work done, confidence, and initiative. Similarly, Fawaz-Yissi and Vallejos-Cartes (2020) also identify key factors for future trends in education, including the use of ICT and greater development of soft skills for employability.

A student’s skills at the time of entry, or student readiness, will enable development of the necessary competencies for academic success and subsequent employment. In addition, students’ first-year performance is significantly correlated with initial work experience outcomes (Lagos et al., 2018), and students are able to shape their own career paths based on their individual profiles (Rasul et al., 2021). Some studies have shown differences in employment readiness in students in technical education, which may be associated with their thinking, teamwork and leadership, problem-solving, and communication skills (Ismail et al., 2018).

It follows from the above that both the academic expectations and skills, or readiness, of TVET students are linked to their subsequent academic development, and due to the short duration of these programs, it is imperative to gain insight into these characteristics upon student entry into TVET in order to better guide and optimize the teaching-learning process. This research aims to characterize the TVET student entry profile based on students’ various expectations and initial skills or readiness.

II. Method

This quantitative research followed a non-experimental, cross-sectional, descriptive design. The variables employed were students’ academic expectations and academic readiness.

The population was made up of all students entering a technical degree at a public university. The non-probability, convenience sample included 183 first-year students from a Chilean public university, of whom 57 (31.2%) were male and 126 (68.8%) were female. All were enrolled in technical degrees at the university at the time of the research; the mean age was 26.9 years, with a minimum of 17 years and a maximum of 54 years.

The instrument used to measure academic expectations was Pérez et al.’s (2015) Spanish adaptation of the Academic Engagement Questionnaire, specifically form A (CIA-A), by Almeida et al. (2003). The questionnaire comprises 35 items about situations and behaviors that students may expect to find in a university setting, rated on a Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The questionnaire evaluates factors relating to vocational engagement, institutional engagement, social engagement, use of resources, and student participation.

In addition, we used the Academic Readiness Scale designed and adapted by Baeza-Rivera et al. (2016) for higher education, which includes 67 items rated on a Likert scale from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree), which inquire about students’ attitudes and behaviors to identify a set of student skills or a level of readiness prior to entering higher education. The scale identifies seven factors: personal self-determination, sociability, emotion modulation, academic self-efficacy, analytical anticipation, effective communication, and academic goal orientation (prospectiva académica).

To begin the process, an invitation was sent through the university’s online platform. This was displayed automatically to all first-year students in technical degrees on accessing the university’s website and was available throughout March 2022. It invited students to participate on a voluntary and anonymous basis and included an informed consent form that took into account the relevant ethical guidelines and safeguards established by the university. The consent form described the objectives and essential aspects of the research, assuring participants that the information would be used confidentially (solely for research purposes) and that there were no risks involved in participating and they were free to withdraw from the study at any time, among other details. Students who consented then proceeded to the questionnaire, where they were asked to provide basic sociodemographic details and rate the items for academic expectations and readiness.

The data analysis process and general structure for the presentation of results were similar to those described by Suárez-Cretton and Castro-Méndez (2022). The SPSS software package (version 25 for Windows) was used to clean the data and reverse-score items where appropriate. Next, reliability indices were calculated for the expectations and academic readiness scales, using Cronbach’s alpha to examine their internal consistency. Descriptive statistics were obtained for the data, including the mean, standard deviation, and percentiles for each of the variables. Compliance with normality assumptions was tested (using values of skewness/kurtosis) and clusters were analyzed using Ward’s method of centroid-based clustering, yielding four clusters of different sizes. Levene’s test was used to analyze the homogeneity of variances for the variables and multiple comparisons were performed to determine possible differences in profiles. Subsequently, one-way ANOVA analyses were performed for each cluster and for each variable and the Scheffé test was used as a post hoc test of comparisons where it was possible to assume homogeneity of variances. All comparisons performed assumed a signficance level of 0.05. In cases where Levene’s test did not allow an assumption of homogeneity of variance, the Games-Howell test was used. Lastly, we identified two groups: one with high academic expectations and another with low expectations, for which the corresponding readiness profile was constructed.

III. Resultados

The instruments employed demonstrated adequate internal consistency, with the following Cronbach’s alpha values. For the academic expectations scale, the values were as follows: vocational engagement .89, institutional engagement .87, social engagement .82, use of resources .82, and student participation .82. For the academic readiness scale, the following values were obtained: personal self-determination .89, sociability .78, emotion modulation .76, academic self-efficacy .63, analytical anticipation .75, effective communication .70, and academic goal orientation .80. These calculations were performed using all the items in each scale. It was therefore not necessary to eliminate any items in this process.

First, a cluster analysis was performed using Ward’s method (centroid-based clustering) to determine academic expectations profiles. This produced four clusters, each characterized by different combinations across the four variables examined. The ANOVA test revealed significant between-group differences in all variables relating to academic expectations and academic readiness. The Scheffé and Games-Howell multiple comparison tests found the between-group differences shown in tables 1 and 2:

| Ward Method | IV | II | IS | UR | PE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mean | 4.42 | 4.15 | 4.31 | 4.51 | 4.00 |

| SD | .36 | .47 | .45 | .38 | .60 | |

| N | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | |

| 2 | Mean | 4.27 | 3.52 | 3.85 | 3.88 | 1.57 |

| SD | .44 | .67 | .59 | .61 | .56 | |

| N | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | |

| 3 | Mean | 3.77 | 3.43 | 3.40 | 3.38 | 2.70 |

| SD | .43 | .52 | .49 | .52 | .52 | |

| N | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | |

| 4 | Mean | 2.81 | 2.05 | 2.52 | 2.64 | 1.45 |

| SD | .47 | .50 | .62 | .68 | .46 | |

| N | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | |

| Total | Mean | 3.95 | 3.47 | 3.66 | 3.74 | 2.67 |

| SD | .68 | .86 | .79 | .83 | 1.16 | |

| N | 183 | 183 | 183 | 183 | 183 | |

| Note: IV: vocational engagement; II: institutional engagement; IS: social engagement; UR: use of resources; PE: student participation. | ||||||

Four groups or clusters can be observed in Table 1. Group 1 is the largest (N = 58) and exhibits the highest values across all variables for academic expectations and is made up of 74.1% women, of whom 34.5% are aged between 17 and 20 years. Group 4 is the smallest, at 15% of the total (N = 27), and shows the lowest values; women make up 66.7% of this group, with 40.7% of women in the group aged between 17 and 20 years. Groups 2 and 3 exhibit intermediate values, with group 2 scoring highest in vocational engagement, social engagement, and use of resources; the group comprises 81% women, 35.7% of whom are aged between 33 and 54 years. Group 3 is notable for a greater score in student participation than group 2 and is made up of 55.4% women, of whom 53.6% are aged between 20 and 33 years. Overall, high scores are observed across all expectations, with the exception of student participation, which shows a mean below the desired value.

| Ward Method | AP | S | ME | AA | AN | CE | PA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mean | 4.70 | 4.37 | 4.11 | 4.27 | 4.79 | 3.79 | 4.65 |

| SD | .25 | .46 | .49 | .26 | .20 | .67 | .24 | |

| N | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | |

| 2 | Mean | 4.30 | 3.94 | 2.84 | 3.86 | 4.46 | 2.72 | 4.16 |

| SD | .38 | .50 | .46 | .22 | .34 | .40 | .36 | |

| N | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | |

| 3 | Mean | 3.99 | 3.62 | 3.63 | 3.96 | 4.19 | 3.74 | 3.90 |

| SD | .42 | .53 | .46 | .26 | .44 | .48 | .44 | |

| N | 69 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 69 | |

| 4 | Mean | 3.06 | 2.83 | 2.80 | 3.30 | 3.34 | 3.00 | 2.96 |

| SD | .60 | .47 | .67 | .50 | .70 | .29 | .48 | |

| N | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Total | Mean | 4.15 | 3.81 | 3.46 | 3.94 | 4.32 | 3.41 | 4.06 |

| SD | .62 | .67 | .71 | .39 | .58 | .68 | .61 | |

| N | 183 | 183 | 183 | 183 | 183 | 183 | 183 | |

| Note: AP: personal self-determination; S: sociability; ME: emotion modulation; AA: academic self-efficacy; AN: analytical anticipation; CE: effective communication; PA: academic goal orientation. | ||||||||

Table 2 shows four groups or clusters. Group 1 exhibits the highest values across all variables for academic readiness and is made up of 74.5% women, 40.4% of whom are aged between 33 and 54 years. Group 4 is the smallest (N = 20) and exhibits the lowest values; this group comprises 70% women, 50% of whom are between 17 and 20 years of age. Groups 2 and 3 exhibit intermediate values, with group 2 (made up of 85.1% women, 44.7% of whom aged between 17 and 20 years) scoring highest in personal self-determination, sociability, analytical anticipation, and academic goal orientation. Group 3 is the largest (N = 69) and is made up of 53.6% women, 31.9% of whom aged between 25 and 33 years; this group scores more highly than group 2 in emotion modulation and effective communication. Overall, the analysis reveals medium to high scores in readiness across all dimensions, although lower scores are observed in emotion modulation and effective communication.

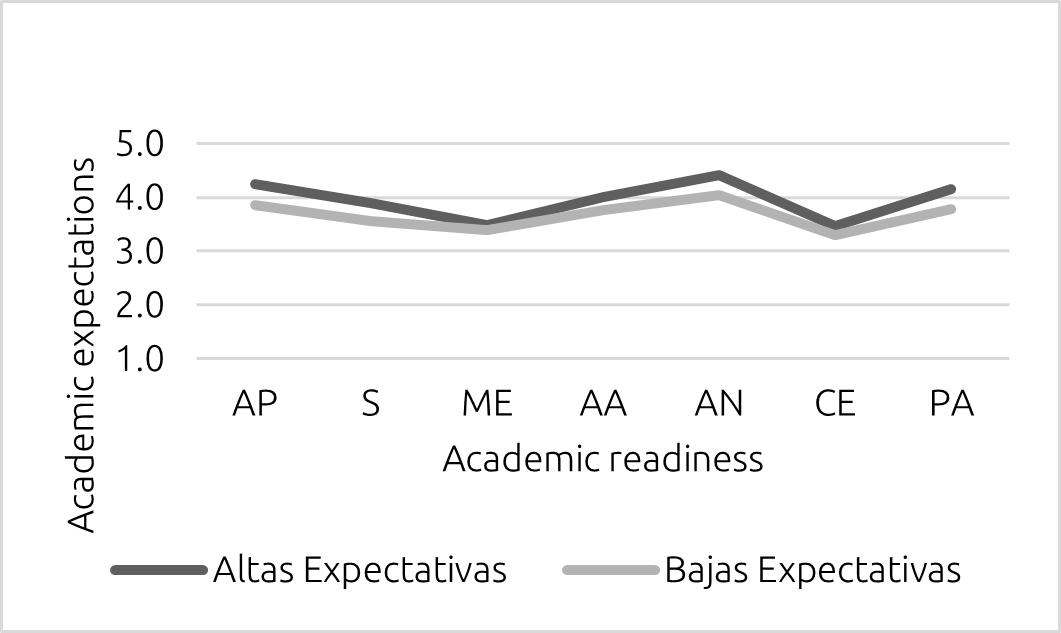

Next, a general readiness profile was obtained for high and low expectation levels (Figure 1).

Translation:

| Altas expectativas | High expectations |

| Bajas expectativas | Low expectations |

Figure 1 shows that, in general, all students exhibit a good level of readiness, above the desired mean value for the scale (3.0); those with greater expectation levels show a greater level of readiness across all variables than those with lower expectations. In both cases, the lowest level of readiness was observed in emotion modulation and effective communication. Table 3 provides insight into the characteristics of these two groups.

| N | Male | Female | 17-20 years | 20-25 years | 25-33 years | 33-54 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High expectations | 140 (76.5%) |

40 (70.2%) |

100 (79.4%) |

41 (75.9%) |

28 (66.7%) |

36 (81.8%) |

35 (81.4%) |

| Low expectations | 43 (23.5%) |

17 (29.8%) |

26 (20.6%) |

13 (24.1%) |

14 (33.3%) |

8 (18.2%) |

8 (18.6%) |

| 183 (100%) | 57 | 126 | 54 | 42 | 44 | 43 |

The lowest expectation level was observed among students aged between 17 and 25 years, who also exhibit the lowest level of readiness upon entry into technical and vocational education.

IV. Discussion

This research aimed to identify the entry profile of students of technical and vocational education and training (TVET) based on their various expectations and initial capabilities or readiness. The results showed high levels of all types of expectations, with the exception of student participation, which is below the desired mean value. This supports students’ academic success, given that expectations influence adaptation and persistence in universities (Gomes & Soares, 2013) and are associated with the quality of academic experiences (Soares et al., 2014). The cluster analysis identified four groups: one with high expectations across all dimensions (the largest group), another with low expectations (the smallest), and two groups with intermediate scores. In all but the group with the highest scores, student participation expectation was below the desired mean value, meaning that the majority of students did not expect to participate in student associations, take on representative roles, or attend student meetings. This is one factor that may diminish learning because a lack of student expectations or goals of this kind could become limitations for learning (Sevilla-Santo et al., 2021); this lesser degree of behavioral engagement may be associated with a perception of lower service quality and value (de Oliveira et al., 2020) and lower student satisfaction (Almeida et al., 2003).

Academic readiness upon entry to the degree program exhibited medium-to-high scores in all the dimensions explored, although lower levels were observed in emotion modulation and effective communication. In general, possessing these skills upon entry equips students to develop the necessary generic skills and would facilitate their adaptation to the university environment (Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019); in particular, support should be made available for students to develop soft skills, such as effective communication, which exhibit lower levels in this study and are indispensable today in the labor market of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Fawaz-Yissi & Vallejos-Cartes, 2020; Mahfud et al., 2017; Saari et al., 2021).

Echoing the results of this research, Ismail et al. (2018) also identified differences in readiness in communication skills among students in technical education. Our cluster analysis showed four groups, the first with a high skill level and comprising mostly older women. A small group (10.9% of the total) showed lower social, emotion modulation, and academic goal orientation skills and may have greater difficulty adapting to their course of study. Two intermediate groups were also found: the largest (37.7% of the total) shows a balanced profile of medium-to-high levels across all skills, while scores across skills for the remaining group were dissimilar and unbalanced, with low emotion modulation and low effective communication.

A general student readiness profile was obtained based on student expectations. Both high-expectation students and those with lower expectations exhibit adequate skill levels (above the desired mean) to pursue higher technical education. This profile is reflective of students with clear objectives, strong self-confidence, and a firm belief that they can achieve their academic goals. This is realistic given the link between feelings of self-efficacy and academic and personal success (Cervantes et al., 2018) and it constitutes a powerful resource for coping with adversity (León et al., 2019). Likewise, students perceive themselves as capable of organizing themselves and employing the necessary strategies and resources to that end.

They display a willingness and a positive attitude toward working and sharing with others, which enables them to engage in collaborative and team efforts, but recognize deficiencies in communicating effectively or using social skills involving oral or written expression, and in managing their own emotional responses, which may be rooted in sociocultural characteristics (Salazar et al., 2020). This lessens their chances of success not just in the immediate present but also in their future working life, given the evidence (from various areas of scientific literature) of the relevance of social skills in enabling individuals to function successfully in society (Huambachano & Huaire, 2018). Despite this, they tend to take a cautious, receptive, and thoughtful approach to the emerging risks in interpersonal relations or academic matters, and when faced with obstacles, they persist and strive to overcome them.

Students with higher expectations obtained higher academic readiness scores. These make up 76.5% of the total and are for the most part older students, over 25 years of age. In this research, older students exhibited higher scores in academic goal orientation, which is associated with a better use of strategies and resources to achieve academic goals. This follows the same direction as findings by Ferraz et al. (2022), who reported that older students of technical and vocational education used more cognitive strategies (sequences of procedures or activities that optimize the acquisition, storage, and use of knowledge) and fewer dysfunctional metacognitive strategies (such as becoming distracted while the teacher is explaining a technique, or ignoring teacher directions) than younger students.

IV. Conclusions

This research adds to knowledge on the profiles of students entering technical and vocational education – an essential consideration given the often shorter duration of these degrees – in order to guide potential interventions at the beginning of these programs and thus improve the teaching process. Many students have adequate academic expectations and skills to successfully pursue technical degrees in a university setting but demonstrate certain limitations due to poorer emotion modulation and effective communication skills. Developing student participation expectations and behaviors could serve as an intervention strategy for improving these skills, given the short duration of technical degree programs. Future lines of research may explore this relationship further. That said, the use of convenience sampling in this study poses some limitations and makes it difficult to generalize the results beyond this sample.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Student Learning Support Unit of Arturo Prat University (UNAP) for its support in this research.

Translation: Joshua Parker

Contribution of each author

Nelson Castro: conceptualization (60%), methodology (80%), formal analysis (50%), writing original draft (50%).

Ximena Suárez-Cretton: conceptualization (40%), formal analysis (50%), writing original draft (50%).

Nicolás Pareja Arellano: methodology (20%), data curation.

Declaration of no conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Source of funding

Unfunded research.

References

Almeida, L. S., Gonçalves A., Salgueira, A. P., Soares, A. P., Machado, J. C., Fernandes, E., & Vasconcelos, R. (2003). Expectativas de envolvimento académico à entrada na universidade: estudo com alunos da Universidade do Minho [Academic involvement expectations upon entry into university: A study with students of the University of Minho (UMinho)]. Psicologia: Teoria, Investigação e Prática, 1, 3-15. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/12108

Baeza-Rivera, M. J., Antivilo, A., & Rehbein, L. E. (2016). Diseño y validación de una escala de preparatividad académica para la educación superior en Chile [Design and validation of an academic readiness scale for Chilean higher education]. Formación Universitaria, 9(4), 63-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062016000400008

Cervantes, D., Valadez, M., Valdés, A., & Tánori, J. (2018). Diferencias en autoeficacia académica, bienestar psicológico y motivación al logro en estudiantes universitarios con alto y bajo desempeño académico [Differences in academic self-efficacy, psychological wellbeing, and achievement drive in university students with high and low academic performance]. Psicología desde el Caribe, 35(1), 7-17. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/psdc/v35n1/2011-7485-psdc-35-01-7.pdf

Conde, Á., Deaño, M., Pinto, A. A., Iglesias-Sarmiento, V., Alfonso, S., García-Señorán, M., Limia, S., & Tellado, F. (2017). Expectativas académicas y planificación. Claves para la interpretación del fracaso y el abandono académico [Academic expectations and planning. Key aspects for interpreting academic failure and dropout]. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 167-176.

de Oliveira, J. H., de Sousa, G. H., Ganga, G. M. D., Mergulhão, R. C. y Lizarelli, F. L. (2020). Antecedents and consequents of student satisfaction in higher technical-vocational education: evidence from Brazil. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20, 351-373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09407-1

Fawaz-Yissi, M. J. y Vallejos-Cartes, R. (2020). Exploring the linkage between secondary technical and vocational education system, labor market and family setting. A prospective analysis from Central Chile. Educational Studies, 56(2), 186-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2019.1703115

Ferraz, A., Pereira, C. P., & dos Santos, A. A. (2022). Relaciones entre estrategias de aprendizaje y motivación en la Educación Técnica Vocacional [Relationships between learning and motivation strategies in vocational technical education]. Revista d e Psicología, 40(1), 491-517. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.202201.016

Gomes, G., & Soares, A. (2013). Inteligência, ha¬bilidades sociais e expectativas acadêmicas no desempenho de estudantes universitários [Intelligence, social skills, and academic expectations in university students’ performance]. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 26(4), 780-789. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722013000400019

Huambachano, A. M., & Huaire, E. J. (2018). Desarrollo de habilidades sociales en contextos universitarios [Development of social skills in university contexts]. Horizonte de la Ciencia, 8(14), 123–130. https://revistas.uncp.edu.pe/index.php/horizontedelaciencia/article/view/300

Ismail, M. E., Hashim, S., Abd Samad, N., Hamzah, N., Masran, S. H., Mat Daud, K. A., Amin, N. F., Samsudin, M. A. y Kamarudin, N. (2019). Factors that influence students’ learning: An observation on vocational college students. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 11(1). https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/3105

Ismail, M. E., Hashim, S., Zakaria, A. F., Ariffin, A., Amiruddin, M. H., Rahim, M. B., Razali, N., Ismail, I. M. y Sa’adan, N. (2018). Gender analysis of work readiness among vocational students: A case study. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 12(1). https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/3106

Lagos, R., Cárdenas, N., & Nass, J. L. (2018). Prácticas en la empresa en formación técnica de nivel superior (formación profesional) en Chile [Internships in higher technical training (vocational training) in Chile]. Opción: Revista de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, (87), 431-457. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7341387

León, A., González, S., González, N. I., & Barcelata, B. E. (2019). Estrés, autoeficacia, rendimiento académico y resiliencia en adultos emergentes [Stress, self-efficacy, academic performance, and resilience in emerging adults]. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 17(1), 129-148. http://repositorio.ual.es/bitstream/handle/10835/7605/2226-7059-1-PB.pdf?sequence=1

Mahfud, T., Kusuma, B. J. y Mulyani, Y. (2017). Soft skill competency map for the apprenticeship programme in the Indonesian Balikpapan Hospitality Industry. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 9(2). https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/1860

Pérez, C., Ortiz, L., Fasce, E., Parra, P., Matus, O., McColl, P., Torres, G., Meyer, A., Márquez, C., & Ortega, J. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de un cuestionario para evaluar expectativas académicas en estudiantes de primer año de Medicina [Psychometric properties of a questionnaire to evaluate academic expectations in first-year students of medicine]. Revista Médica de Chile, 143(11), 1459-1467. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872015001100012

Pugh, G., & Lozano-Rodríguez, A. (2019). El desarrollo de competencias genéricas en la educación técnica de nivel superior: un estudio de caso [Developing generic skills in higher technical education: A case study]. Revista Calidad en la Educación, (50), 143-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.31619/caledu.n50.725

Rasul, M. S., Mohd Nor, A. R. y Amat, S. (2021). Construction of TVET students’ career profile pathways. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 13(1), 139–147. https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/7829

Saari, A., Rasul, M. S., Mohamad-Yasin, R., Abdul-Rauf, R. A., Mohamed-Ashari, Z. H. y Pranita, D. (2021). Skills sets for workforce in the 4th industrial revolution: Expectation from authorities and industrial players. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 13(2), 1–9. https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/JTET/article/view/7830

Salazar, M., Mendoza-Llanos, R., & Muñoz, Y. (2020). Impacto diferenciado del tiempo de formación universitaria según institución de educación media en el desarrollo de habilidades sociales [Differential impact of duration of university education by high school on the development of social skills]. Propósitos y Representaciones, 8(2), e416. http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2020.v8n2.416

Sevilla-Santo, D. E., Martín-Pavón, M. J., Sunza-Chan, S. P., & Druet-Domínguez, N. V. (2021). Autoconcepto, expectativas y sentido de vida: Sinergia que determina el aprendizaje [Self-concept, expectations, and life purpose: A synergy that determines learning]. Revista Electrónica Educare, 25(1), 1-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/ree.25-1.12

Siteal Unesco. (2019). Educación y formación técnica y profesional. [Technical and vocational education and training]. https://siteal.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/sit_informe_pdfs/siteal_educacion_y_formacion_tecnica_profesional_20190607.pdf

Soares, A., Francischetto, V., Dutra, B., de Miranda, J., Nogueira, C., Leme, V., Araújo, A., & Almeida, L. (2014). O impacto das expectativas na adaptação acadêmica dos estudantes no Ensino Superior [The impact of expectations on students’ academic adaptation in higher education]. Psico-USF, 19(1), 49-60. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712014000100006

Suárez-Cretton, X., & Castro-Méndez, N. (2022). Perfiles de gratitud, necesidades psicológicas y su relación con la resiliencia en estudiantes no tradicionales [Gratitude profiles, psychological needs, and their relationship with resilience in non-traditional students]. Estudios sobre Educación, 43, 115-134. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.43.006

Valdebenito, M. J. y Sepúlveda, L. (2021). New configurations of labour insertion processes. The case of secondary technical and vocational education and training students in Chile. International Journal of Social Welfare, 32(1), 32-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12508