Gender and School Improvement in Primary Education

How to cite: Aierbe, A., Intxausti, N. y Bartau, I. (2024). Gender and school improvement in primary education. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 26, e13, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2024.26.e13.5291

Abstract

This work explores good practices in favor of gender equality in high or low-efficacy elementary schools in the Basque Autonomous Community. This mixed-methods study employs a descriptive, exploratory, and explanatory design with questionnaires, interviews, and discussion groups. Administrative teams, inspectors, and teachers report a wide range of coeducational activities in accordance with school efficacy, although these are not always included in plans or programs. The results show differences in the involvement of schools and teachers and in their assessment of gender socialization, depending on personal factors (age, sex, teaching experience, and seniority in the school) and contextual ones (school size; economic, social and cultural status; immigration; high or low school efficacy). We conclude that there is a need to focus on structural or organizational aspects and the provision of more experiential and contextualized education.

Keywords: gender, primary education, coeducation, school improvement.

I. Introduction

In education, as in all areas of society, changes in gender relations are currently taking place (Quiñones, 2011). Therefore, there is a growing interest in creating diagnostic procedures and educational resources aimed at identifying and highlighting good practices to support administrative teams and teachers in providing an education rooted in inclusion and coeducation (Pallarés, 2015).

It is at school, and specifically in primary education, together with the family and other educational players, where, in addition to encouraging students to acquire a solid basis of habits, knowledge and skills, the foundations of gender construction will be established. However, schools can reinforce different and hierarchical ways of socialization and social positioning, gender stereotypes and behaviors acquired by students in their families, or try to eradicate them (Azorín, 2014).

The purpose of coeducation is “to dissolve the mechanisms that enhance gender discrimination not only in formal education but, also, in ideology and practice” (Subirats and Brullet, 1988 cited by Macías, 2018, p.350). It is aimed at children to develop as autonomous beings, capable of caring for others and themselves, of establishing egalitarian and fair relationships, of carrying out activities without limitation due to sexist prejudices, and that these be perceived as equally relevant and prestigious both those associated with men and women (Angulo et al., 2017).

Nevertheless, despite educational policies, resources and collective efforts aimed at gender equality, discriminatory and sexist attitudes and behaviors among students persist, therefore it is necessary to approach coeducation from a broader perspective so that the values of equality become the basis of their socialization process (Macías, 2018).

The Teaching and Learning International Survey TALIS 2018 (OECD, 2019) in reference to equity of the Spanish educational system in primary education, points out that, according to administrative teams, in 9 out of 10 schools, specific policies against gender discrimination are carried out. The profile of the teaching staff has an average age of 43 years, 50% have 15 or less years of experience and are mostly women (76%), although the proportion of female principals is lower (62%). This imbalance has led to policies that intend to attract men towards the teaching profession (Drudy, 2008; OECD, 2019).

Even though the participation of teachers in professional development activities and continuing education courses in primary education is high (95%), for the school’s administration one of the areas of “great need” that must be addressed through training is equality and diversity (23%) (OECD, 2019). In this vein, Azorín (2014) found that 46.1% of teachers had received training in coeducation, compared to 53.9% that had not. Teachers did not consider it necessary for schools to have a person responsible for coeducation who advocates for equal education and, through their efforts, permeates the organization and daily activities of the schools. Their attitude towards implementing coeducation in their schools was favorable, although female teachers showed greater awareness of gender discrimination (Quiñones, 2011; Rebollo et al., 2011).

Coeducation continues to be an unresolved issue for both active and trainee teachers (García and de la Cruz, 2017; Rausell and Talavera, 2017). The importance of incorporating equality education into the teacher training curriculum must be emphasized, including addressing misconceptions such as “the mirage of equality” or the false belief that gender equality already exists (Gobierno Vasco, 2019; Valdivielso et al., 2016). Furthermore, it has been proven that teaching experience in addition to training on the prevention and treatment of school coexistence problems does not, in itself, guarantee greater knowledge of these issues (Álvarez-García et al., 2010).

The study by Aristizabal et al. (2018) conducted in the Basque Autonomous Community (CAV) concludes that, although most professionals participating in coeducation training consider it necessary, they are unaware of its implications and the specific actions required to foster it. Therefore, it is necessary to promote programs and actions in favor of coeducation, guided by conflict resolution and the prevention of sexist attitudes and behaviors, with the involvement of the entire educational community (including students).

There is no doubt that, in addition to training, educational organization is a key element in achieving gender equality, as it constitutes the axis around which measures and actions are articulated to make possible the establishment of a school culture based on equity and free of sexism (Azorín, 2014).

Angulo et al. (2017), within the framework of the Basque Institute for Educational Evaluation and Research ISEI/IVEI of the Basque Government's Department of Education, carried out a diagnosis using the 2015 Diagnostic Assessment test. They found that in primary school, equality issues are not taken into account in half of the subject curriculum, 55% address them in specific activities, and charter (subsidized) schools deal more with the issue of detecting and preventing gender violence (44.4%) than public schools (38.3%). The authors point out that at this educational level, more attention is paid to the use of non-sexist images and language than to reinforcing autonomy and joint responsibility and reviewing shared spaces.

It should be emphasized that one of the pillars of improving school effectiveness is equity. The literature has shown that educational activity depends to a large extent on the socioeconomic and cultural context. For this reason, this study has also considered an analytical approach that allows for a more accurate and equitable assessment of the effect of schools. Thus, the definition of high and low effectiveness considered in this study is based on the effectiveness model consisting of statistically controlling the effect of the covariates associated with the context in order to isolate the effect of the school and consider it as an indicator of effectiveness or ineffectiveness (Lizasoain, 2020). An effective school is defined as “one that achieves the comprehensive development of each and every one of its students, beyond what would be expected given their previous performance and the socioeconomic and cultural situation of their families” (Murillo, 2005, p. 30). From this perspective, schools whose students perform significantly below expectations can be considered ineffective schools.

Among the various tools and indicators to be adopted to measure a gender-friendly environment and intervene in schools is the Second Coeducation Plan for the Basque education system (2019-2023) of the Basque Government's Department of Education, a benchmark that has been adopted in this research, specifically with regard to the eight pillars of coeducation for primary education.

After analyzing the related research, and within the framework of studies on school effectiveness and improvement, the objective of this study is to delve into the perceptions that teachers, administrative teams, and inspectors of primary schools in the Basque Autonomous Community have regarding gender equality and to identify good coeducational practices.

The specific objectives are:

- To ascertain the assessment made by primary school teachers in the Basque Autonomous Community (CAV) of how gender socialization is addressed in schools, based on personal factors (gender, age, years of teaching experience, and seniority at the school) and contextual factors relating to the school (public or subsidized, socioeconomic and cultural index (ISEC), size, percentage of immigrant students, and high or low academic performance).

- Delve into structural and organizational aspects and good coeducational practices in primary schools in the CAV from the perspective of teachers, administrative teams, and educational inspectors.

II. Method

This is a descriptive-exploratory-explanatory study using mixed methodology (quantitative and qualitative) in which, once primary schools with high and low academic performance had been characterized, the treatment of gender socialization was examined in depth from the perspective of teachers, administrative teams, and educational inspectors. This work is based on research on school effectiveness and improvement in collaboration with the Basque Institute for Educational Evaluation and Research (ISEI-IVEI).

The study is based on the entire population, i.e., all primary schools in the Basque Autonomous Community's education network. In accordance with the criteria for effectiveness adopted (explained in the Procedure section), 29 schools were selected, 14 with high effectiveness (CAEF) and 15 with low effectiveness (CBEF).

The quantitative study involved 224 teachers from these schools, 71 (31.7%) from the public network and 153 (68.3%) from the subsidized network; 133 (59.4%) CAEF and 91 (40.6%) CBEF. Of the total number of teachers, with the exception of 18 for whom no data is available, 154 are women (68.8%) and 52 are men (23.2%), with an average age of 43.97 (SD 9.93), an average of 19.34 years of teaching experience (SD 10.37), and an average of 14.07 years at the school (SD 10.37).

The qualitative study involved the administrative teams and educational inspectors from the 29 schools and teachers (47 teachers in total, 22 men and 25 women) who participated in nine discussion groups.

2.1 Instruments

The semi-structured interview with administrative teams and educational inspectors addresses, in addition to gender socialization, eight areas related to school effectiveness and improvement (training and innovation projects, methodology, diversity, evaluation, organization and management of the school, leadership, environment, and family-school-community relations).

The script for the discussion groups with teachers is designed to gather their views on the educational reality (the strengths, weaknesses, difficulties, and educational practices of the schools), including gender socialization, in which they are immersed so that improvement plans can be designed and implemented.

In addition, teachers completed an ad hoc online questionnaire to gather information about everyday practices at the school. The questionnaire consists of 92 items referring to eight areas related to effectiveness and improvement, with 12 items corresponding to the area of gender socialization. The statements were rated on a scale of 0 to 10, from lowest to highest rating. A score of 8 to 10 represents maximum agreement (or importance), 6-7 represents average agreement or importance, and 5 or less represents disagreement or insufficient importance. The average time to complete the questionnaire is 15 minutes. In terms of reliability and validity, the questionnaire was based on an exhaustive literature review and the identification of the dimensions of school effectiveness found in previous research (ISEI-IVEI, 2013, 2015), and was reviewed by a committee of experts (α = .97). Specifically, for the area of gender socialization, the Basque Government's Second Coeducation Plan was taken into consideration. Cronbach's alpha for this dimension is α = .82.

2.2 Procedure

It is based on the census sample of the Diagnostic Assessments (DA) applications from five editions carried out in primary schools in the Basque Autonomous Community, and schools with high or low effectiveness are selected through multilevel regression analysis, considering the types of criteria specified in the work of Lizasoain (2020). The difference between the score obtained and the expected score in each school provides the residual that can be considered an indicator of the school's level of effectiveness. The term residual refers to the difference between the average score obtained in the Diagnostic Assessments and the expected average score, taking into account contextual factors at the school, including the ISEC (ISEI-IVEI, 2015, p. 49).

A school is considered to be highly effective when, once contextual factors have been controlled, it obtains a higher than expected average score (positive differential or residual score) in the three basic instrumental competencies (Spanish, Basque, and mathematics).

The CAEFs selected for the study were those which, considering the three competencies assessed (Spanish language, Basque language, and mathematics) in the five editions of the ED, obtained a high average residual above the 80th percentile. For the CBEFs, the average of the differences that were in the bottom 20% of all schools in the Basque Autonomous Community was considered. These cut-off points were established based on the number of schools that were deemed sufficient and that could be studied given the resources (human and material) available to the research team, since they would subsequently be analyzed in depth through case studies.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with administrative teams and educational inspectors at the 29 selected schools, and discussion groups were held with teachers. Based on the data collected, an ad hoc questionnaire was developed and completed by teachers at the selected schools using Google Forms.

Informed consent was obtained from those who participated in the study in accordance with Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights.

2.3 Data Analysis

The quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS 24 software. Once the schools were selected according to efficacy criteria using multilevel regression statistical procedures (hierarchical linear models), descriptive statistics (sum, mean, standard deviation, and frequencies) were used for the questionnaire data; as well as reliability analysis (Cronbach's alpha); the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z test and nonparametric tests: Mann-Whitney U test for comparing means between two groups and Kruskal-Wallis test for comparing means between more than two groups, and effect size.

On the other hand, qualitative data was processed using the NVivo10 program. The categories or nodes emerging from the information obtained in the interviews and discussion groups were determined, taking as references the eight pillars of coeducation specified for the Primary Level by the Basque Government's Second Coeducation Plan 2019-2023 (p. 34), and were analyzed using coding matrix queries and coding comparison queries.

III. Results

3.1 Teacher evaluation

The overall assessment of teachers regarding the school's approach to gender socialization (M = 7.74, SD 1.62) is as follows: 66.4% believe that the school attaches the utmost importance to coeducation, 23.4% indicate that it is given medium importance, and 10.2% consider it insufficient. Regarding the proportional distribution of management positions (M = 6.98; SD = 2.487) between men and women: 49.1% strongly agree, 13% agree, and 15.2% disagree. Two-thirds of teachers strongly agree that they identify situations of gender discrimination among students or teachers (M = 8.11, SD 2.50). Of the total 72.2%, 44.2% of teachers give the maximum score of Agree; 11.6% agree and 16.4% disagree.

Among the actions that the school carries out in relation to gender equality, they point out that: teachers participate in training in this area (M = 6.93; SD = 2.717), the school has strategies to promote gender equality (M = 7.42; SD = 2.020); the school evaluates gender equality among students (M = 6.26; SD = 2656); student grouping seeks heterogeneity (M = 8.40; SD = 1.841); relationships between teachers and students are positive (M = 8.11; SD = 1.361); relationships between students are satisfactory (M = 7.39; SD = 1.460); the school environment is positively valued (M = 7.52; SD = 1.759); students are involved in matters of school life (M = 6.88; SD = 1.959); and the school carries out actions to involve male parents (M = 5.91; SD = 2.617).

In relation to personal factors, the gender of the teachers who completed the questionnaires was only significant in one item: female teachers consider, to a greater extent than male teachers, that students are involved in matters of school life (M (SD) = 7.11 (1.80) vs 6.31 (2.26); Z = -2.423; p = .015).

By age, significant differences have been found in the identification of gender discrimination, as both age groups, the youngest (35 years old or younger, M = 8.27, SD 2.51) and those who follow (36-50 years old, M = 8.43, SD 2.30), score higher than those over 50 (M = 7.48, SD 2.72) [X2 = 8.282; p = .016]. In addition, those under 35 years of age are more likely (M = 8.11, SD 1.98) than other teachers (those aged 36-50, M = 6.81, SD 2.75, and those over 50, M = 6.38, SD 2.97) to think that there is a proportional distribution of management positions between men and women at the school [X2 = 11.419; p = .003].

With regard to teaching experience, those who have been in the profession for 10 years or less are more likely to agree (M = 7.63, SD 2.49) compared to those who have been in the profession for 31 years or more (M = 6.05, SD 2.89), that management positions at the school are distributed proportionally between men and women [X2 = 8.573; p = .036]. On the other hand, those who have been at the school for 21 to 30 years, compared to those who have been there for 10 years or less, participate more in training on gender equality (M (D.T.) = 7.62 (1.98) vs 6.69 (2.45); Z = -1.964; p = .050).

In order to delve deeper into the analysis of contextual variables and enable comparisons to be made, two groups of teachers have been established based on the median percentile for each of the variables (ISEC, school size, percentage of immigrant students), with one group above and the other below the median percentile value. Thus, it can be observed that teachers whose schools have a lower ISEC (percentile less than or equal to -.08), compared to those with a higher ISEC (percentile greater than -.08), consider that they participate more in training on gender equality (M (SD) = 7.49 (2.31) vs 5.88 (2.46); Z = -5.059; p = .000). However, no significant differences were found based on the type of school (public/subsidized).

Teachers at smaller schools (percentile less than or equal to 47.60), compared to those at larger schools (percentile greater than 47.60), consider that they participate to a greater extent in training on gender equality (M (SD) = 7.23 (2.39) vs 6.51 (2.56); Z = -2.240; p = .025); they strive for heterogeneous grouping of students (M (SD) = 8.65 (1.59) vs. 8.06 (2.09); Z = -2.218; p = .027); the school has coeducational strategies (M (SD) = 7.80 (1.84) vs 6.90 (2.13); Z = -3.451; p = .001); equal treatment among students is evaluated (M (SD) = 6.72 (2.49) vs 5.62 (2.75); Z = -2.588; p = .011); positions are distributed equally between men and women (M (SD) = 6.63 (2.84) vs. 7.46 (2.47); Z = -2.037; p = .042); the teacher-student relationship is good (M (SD) = 8.32 (1.24) vs 7.83 (1.46); Z = -2.565; p = .010); students are involved in matters of school life (M (SD) = 7.37 (1.76) vs 6.18 (2.02); Z = -4.348; p = .000); and the school takes action to involve fathers in their children's education (M (SD) = 6.25 (2.51) vs 5.43 (2.69); Z = -2.028; p = .043).

In addition, teachers at schools with higher rates of immigrant students (percentile greater than .03) compared to schools with lower rates (percentile equal to or less than .03) believe that they participate more in training on gender equality and that the school has more strategies in place to promote gender equality.

Given that the schools were selected based on effectiveness criteria (CAEF or CBEF), we analyzed whether teachers' assessment of gender equality varied depending on which school they belonged to.

As shown in Table 1, significant differences were found in favor of teachers at highly effective schools in the following items: teachers participate in training on gender equality; student grouping seeks heterogeneity; students are involved in resolving matters of school life; the school has strategies to promote gender equality; and the school evaluates gender equality among students.

| Item | CAEF M (SD) | CBEF M (SD) | Z (p) | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher training on gender equality. | 7.55 (2.33) | 5.92 (2.40) | -5.321 (.000**) | -0.36 |

| Heterogeneous grouping of students. | 8.67 (1.50) | 7.97 (2.22) | -2,196 (.028*) | -0.15 |

| School strategies to promote equality. | 7.66 (1.93) | 7.05 (2.10) | -2.597 (.001*) | -0.17 |

| Assessment of equal treatment among students. | 6.61 (2.54) | 5.71 (2.75) | -2,289 (.022*) | -0.15 |

| Students involved in resolving matters of school life. | 7.19 (1.81) | 6.38 (2.10) | -2.909 (.004*) | -0.19 |

| Relationships between teachers and students are positive. | 8.31 (1.11) | 7.80 (1.64) | -1.882 (.060) | -0.13 |

| Relationships between students and teachers are satisfactory. | 7.50 (1.32) | 7.21 (1.64) | -.768 (.443) | -0.05 |

| Proportional distribution of positions. | 6.91 (2.78) | 7.08 (2.62) | -.318 (.751) | -0.02 |

| Perception of gender discrimination. | 8.20 (2.44) | 7.96 (2.61) | -.405 (.685) | -0.03 |

| Actions to involve fathers in their children’s education. | 6.17 (2.57) | 5.49 (2.65) | -1.947 (.051) | -0.13 |

| Overall assessment of the school environment. | 7.62 (1.71) | 7.35 (1.83) | -1.947 (.296) | -0.13 |

| Overall assessment of the treatment of gender socialization at the school. | 7.88 (1.52) | 7.50 (1.77) | -1.638 (.101) | -0.11 |

| ** significance at the .01 level and *significance at the .05 level | ||||

3.2 Organizational aspects and good coeducational practices

This section presents the results relating to the structural level or organizational environment of the schools and to the coeducational practices that, in the opinion of the teaching staff (teachers, administrative teams, and educational inspectors), are the most noteworthy.

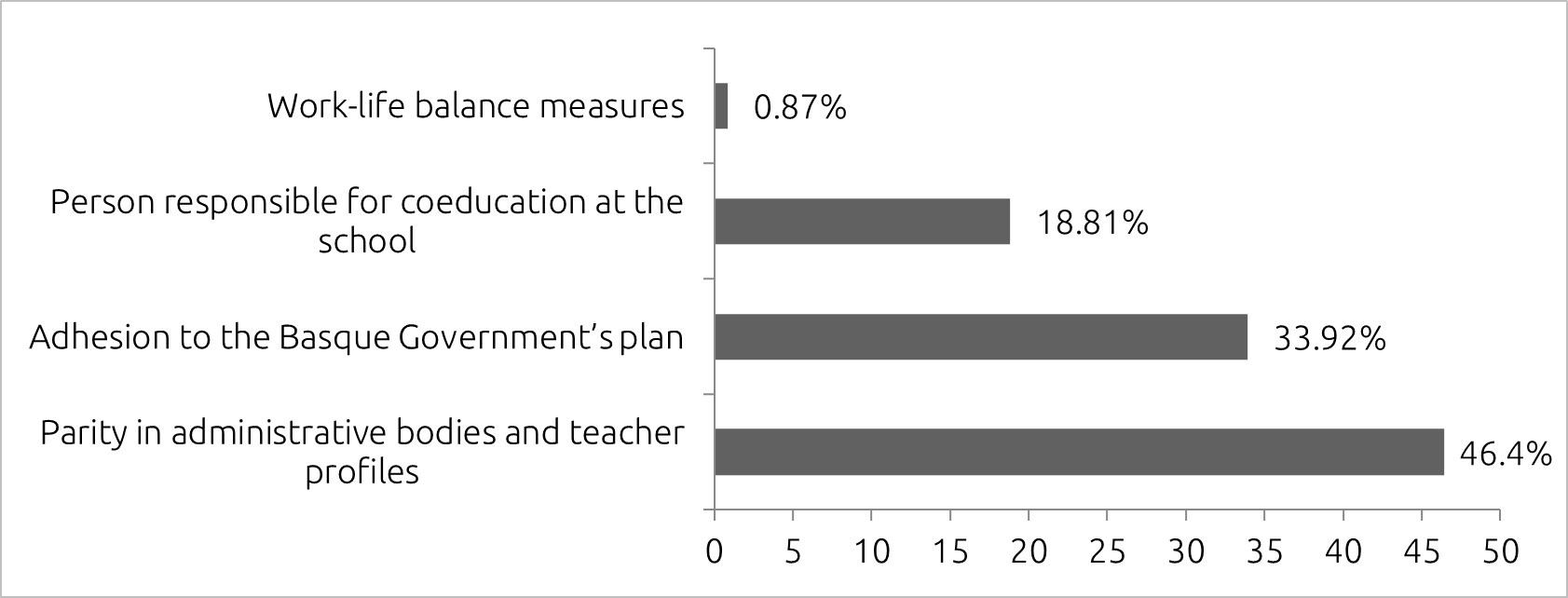

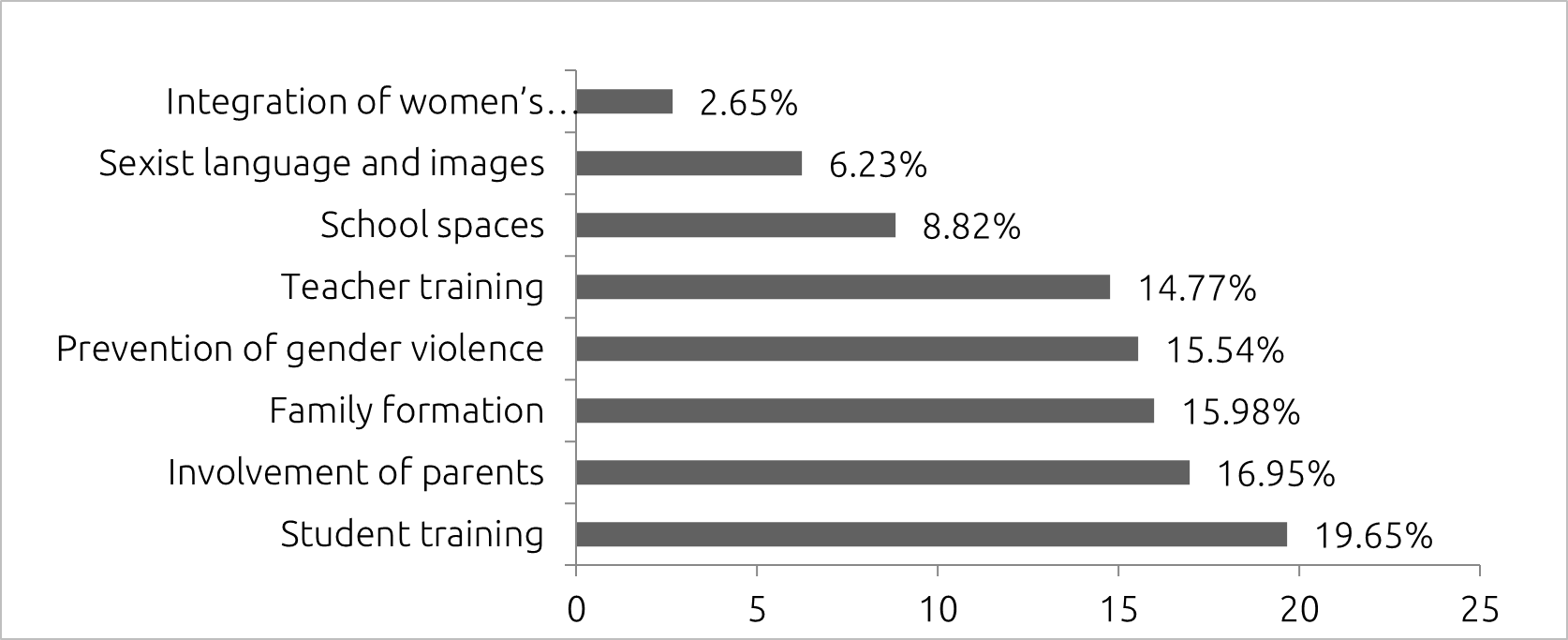

Figures 1 and 2 show the coding frequencies in the subcategories, respectively.

With regard to parity in administrative bodies, there are no substantial differences between high and low-efficacy schools in terms of the composition of women and men in the school’s single-person and collegiate bodies. There is variety in the composition of management teams, although there is a certain predominance of schools where these teams are made up entirely or mostly of women. In the school board, however, it is more common for men to be in charge. The composition of the Parents' Association (AMPA) varies, although women often predominate, with the exception of one case in which men are in the majority. Just over half of the educational inspection staff at these primary schools are women, and in all of them, female teachers predominate in the early grades, a fact that contrasts with the scant reference to work-life balance measures.

Of the 14 schools for which information is available, 6 are registered and implement the Basque Government's Equality Plan (4 subsidized and 2 public), 4 of which are highly effective and 2 of which are less effective. Another 8 schools indicate that they do not follow the Plan (4 highly effective and 4 with low effectiveness) but have specific actions to follow programs from entities such as the Provincial Council (Gehilan) or Emakunde (Nahiko) or other entities other than the Department of Education (e.g., Irudi Berriak, Biziak, etc.). Networking with other schools is another option, either on the subject in general or on specific actions, for example, by adopting a shared commitment to promoting sport among female students. The person responsible for coeducation in schools varies, as it may fall to the headteacher, the guidance counselor, the head of studies, a committee set up for this purpose (within the School Council), or teachers who are more aware of the issue.

Furthermore, the coeducational actions and strategies described by participants in interviews and discussion groups have been examined in depth, and it has been found that, in general, all schools, whether highly effective or less so, carry out activities aimed at promoting gender equality. Table 2 summarizes the most noteworthy coeducational good practices, organized according to the Basque Government's Second Coeducation Plan (2019).

| Critical thinking in the face of sexism. | Training for the entire educational community. |

| Networking with other schools. | |

| Detection of gender discrimination among students. | |

| Talks for pupils/students as speakers. | |

| Language and images: non-sexist use. | Detecting sexist language inside and outside the classroom. |

| Review of curriculum materials. | |

| Specific materials addressing equality (stories, videos, short films, programs, etc.). | |

| Identify stereotypes in media preferences and their use. | |

| Integrating women's knowledge and their contribution. | Highlighting the social and historical contribution of women by taking advantage of interest in the Internet. |

| Conflict management and coeducational interaction. | Heterogeneous grouping of students. |

| Cooperative methodology and positive socialization. | |

| Student involvement in matters of school life. | |

| Training students in conflict mediation. | |

| Student assistant (Bakeola Project). | |

| Figure of the “older friend”. | |

| Personal autonomy and financial independence. | Highlighting professional segregation by gender. |

| School spaces, extracurricular and complementary activities. | Equal use of spaces. |

| The cooperative methodology promotes a positive atmosphere in the playground. | |

| Teaching staff participating in cooperative games in the playground. | |

| Promote sports among female students in collaboration with other schools. | |

| “Student assistant” in the playground. | |

| Emotional and sexual education in equality. | Training based on real-life experiences and using engaging materials (rap, theater, graffiti, etc.). |

| Prevention and action against gender violence. | Prevention of conflicts based on sexual orientation. |

| Establish a course slogan for improving student interaction and preventing gender violence. | |

| Positive interaction notebook to be shared between the school and families. | |

| Figure of the child protector. |

Training activities related to the development of critical thinking about sexism and the identification of actions that undermine gender equality are particularly noteworthy, for example: “On Friday, a boy touched a girl's butt, I don't know... well, we're there to tell them to be respectful. We deal with that kind of thing all the time, but anyway...” (Discussion Group 25080). They also refer to the detection of sexist language among students or sexist attitudes in interactions between teachers and families: "...when treating them (females) as ‘dude..., buddy..., mate...’, they don't talk to you like that... Or me, as a tutor, when they (father and mother) come to the tutoring meetings and the only one who speaks is the father" (Discussion Group 25080). With regard to curriculum materials, the coeducational materials used are provided by the Basque Government, Ararteko, Emakunde, Berritzeguneak, and local councils.

Regarding the integration of women's knowledge, an administrative team refers to working on it by taking advantage of the students' adherence to digital media and the internet, researching women who had had been made invisible by society, as well as their contributions. And, in turn, trying to delve deeper with students into the gender stereotypes that may arise when selecting media content and characters:

YouTubers are their role models, and when you ask them, “Do you watch the news? Have you seen this or that?” The boys [respond] with school sports, and the girls with many fashion bloggers, and from there, you ask, “What happened? Who is this Nobel Prize winner?” (Administrative Team 26092).

Another action mentioned by teachers is raising awareness of men and women who have broken stereotypes in their professional lives:

On March 8th, we increasingly try to give women the opportunity to come and talk about things related to their professions, not just limited to “feminine” professions. For example, a mother who is a geologist gave a presentation and spent time with the students in the laboratory. (Discussion Group 31262).

In relation to conflict management and coeducational interaction, in addition to specific training, cooperative methodology, and student involvement in matters of school life, actions to promote the visibility of egalitarian masculinities stand out, through the figure of the “older friend” proposed by the teaching staff:

When five-year-olds enter the playground for the first time, they feel a little vulnerable, so we saw the need for one of the older children (from sixth grade) to act as their guide, accompanying them during their first days at school, and then we encouraged joint activities. The “older friend” will be with them, explain things to them, talk to them, and pay close attention to them during those days. A very nice relationship develops. (Discussion Group 30316).

Another option, which arose spontaneously at the suggestion of the students, is the role of “student assistant,” according to the teachers:

They formed a group, created their own logo, and then we gave them vests to identify them (as helper friends) in the playground. They would go around and, if they saw someone standing alone, they would approach them and encourage them to join the group, but the nice thing is that it came from them. (Discussion Group 30316).

Along the same lines, the equal use of spaces is analyzed, ball-free days are established, and teachers organize and participate in cooperative games with students in the playground.

One noteworthy practice is to establish a course slogan that contributes to the prevention of violence among students and is shared with families through the positive interaction notebook: "This course is 'be a witness and then speak up.' Students have started to talk about things, which they didn't do before. And those who don't dare to speak up have the physical or digital mailbox." (Discussion Group 31262).

In some schools, students have received training on bullying, cyberbullying, and gender violence prevention starting in the third year of primary school. Also, for the prevention of gender violence, some schools have several filters through which to observe, analyze, and respond peacefully to conflicts (regulations, observatory, assembly, tutoring sessions, among others). However, the administrative team of one school insists that:

As experts point out, traditional prevention methods such as “don't do this” and “I'll show you a video and tell you...” do not work; it is necessary to work on it from an emotional intelligence perspective and with all parties involved, taking care of the message from the school, families, and society. (Administrative Team 29128).

Finally, when analyzing family involvement, it has been found that, in general, mothers participate more than fathers. In both high and low-effectiveness schools, mothers communicate more with the school and participate more in meetings and other educational activities, while fathers are more likely to intervene in cases of conflict or problems (academic and behavioral) or in relation to structural issues at the school. Even so, they believe that fathers are becoming increasingly involved.

Digital tools have a positive influence on the education of families in coeducation, as reported by a low-efficiency center: “They have a Moodle platform where, in the tutors' section, they have posted the material that students had to review with their parents at home, and it has been well received” (Administrative team 29128).

The existence of diverse family structures, especially in the case of separated families or those with shared custody, is a normalized situation, and schools, whether highly effective or less so, are adapting to the new requirements that this poses.

When the proportion of immigrant students is high in a school, teachers point out that they must take into account the cultural differences of families in terms of gender roles. This can sometimes make it difficult to manage sexist attitudes in relationships with families and students, stereotypes, or low expectations on the part of students due to the influence of their environment. Something that, in their opinion, seems to counteract this is the visibility and modeling of former students who contribute to breaking the cycle of expected roles.

IV. Discussion and conclusions

In general, two-thirds of primary school teachers believe that their school places medium or high importance on gender equality and identifies sexist situations. Younger teachers say they identify more gender discrimination and, together with those with less teaching experience, believe that there is greater parity in administrative positions, while those with more seniority at the school participate more in training on gender equality. Along the same lines, Valdés-Cuervo et al. (2018) point out that professional experience does not guarantee greater knowledge about gender equality.

The assessment of coeducation training given by participating teachers reached an average level in this study, unlike the study by González-Barbera et al. (2012), who found that teachers who negatively assessed training in any of its aspects tended to be young men who had recently entered the teaching profession and worked in public schools.

Female teachers, more so than male teachers, believe that students are involved in matters of school life and interaction with others. This may be associated with their greater sensitivity to interpersonal relationships and regulation (Pena et al., 2012). It should be noted that the number of women who participated in this research tripled that of men, which also points to their greater sensitivity towards coeducation (Azorín, 2014; Rebollo et al., 2011).

Contextual characteristics also influence teachers' assessments, as teachers at schools with a low ISEC, smaller size, and/or higher immigration rates consider that they participate more in training on gender equality. Teachers at smaller schools or schools with higher immigration rates also report having more strategies in place at their schools to promote gender equality.

Teachers at high-performing schools are rated more highly than those at low-performing schools, not only in terms of their participation in gender equality training or the school's strategies to promote equality, but also in terms of aspects related to student involvement. This result should be viewed with caution, as it may be due to the fact that participation by teachers at low-performing schools has been lower than at high-performing schools.

In terms of the structural and organizational aspects of schools, female teachers predominate at the primary level (Basque Statistics Institute [EUSTAT], 2019; OECD, 2019), although there is an increasingly favorable attitude toward the recruitment of male teachers (Drudy, 2008; OECD, 2019). The lack of reference to work-life balance in the participating schools seems to indicate a disconnect between the advances in current legislation in this area and the reality (Nieto, 2019).

It has also been noted that the administrative bodies of participating schools are diverse in composition and that there is no single person responsible for equality within them (Azorín, 2014; Ugalde et al., 2019). Although the results of this research are not conclusive, it is important to emphasize that among the key organizational elements for coeducation are stable structures responsible for promoting it, adherence to a coeducation plan, and training (Basque Government, 2019).

Good coeducational practices have been explored in depth and, in general, it has been found that all participating schools, whether highly effective or less so, carry out activities aimed at promoting gender equality, although these are not always included in plans or programs, which vary, and the involvement of schools and teachers varies. In any case, when the perceptions of teachers are complemented by those of administrative teams and educational inspectors, whose opinions do not always coincide, a more diverse and detailed view of how gender socialization is addressed in schools is obtained.

However, this whole range of actions in favor of gender equality in primary education only makes sense if they are included in comprehensive projects in schools, with the introduction of a gender perspective in the curriculum, collaboration between institutions, effective coordination when proposing initiatives or plans, and evaluation of their real impact (Ugalde et al., 2019).

Training modalities for teacher professional development should be reviewed in order to move toward more experiential and contextualized initiatives (Aristizábal et al., 2016) that promote changes in their social representations and the ability to generate critical thinking and their own responses with a gender perspective. This requires leadership related to collaborative management based on common tasks or projects, including co-educational ones, aimed at professional cooperation and innovation (Valdivielso et al., 2016).

With regard to families, in addition to promoting actions to increase the involvement of fathers, it is necessary to strengthen coeducational programs so that there is close parental collaboration (Ceballos, 2014). Addressing the cultural diversity of families and gender is another demand that teachers make explicit and that should be considered in training proposals.

In future studies, in addition to considering the aspects mentioned above, it would be advisable to include the voices of families and students themselves in order to continue advancing toward school improvement rooted in inclusion and coeducation.

Authorship contribution

Ana Aierbe Barandiaran: methodology, conceptualization and writing.

Nahia Intxausti Intxausti: methodology, conceptualization and writing.

Isabe Bartau Roja: methodology, conceptualization and writing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Source of funding

This research has been carried out within the project [PGC2018-094124-B-100] funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIU), the State Research Agency (AEI) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), and within the GANDERE Research Group (GIU21/056) funded by the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Basque Institute for Educational Evaluation and Research (ISEI-IVEI) for providing access to the Diagnostic Assessment databases.

References

Álvarez-García, D., Rodríguez, C., González-Castro, P., Núñez, J. C. y Álvarez, L. (2010). La formación de los futuros docentes frente a la violencia escolar. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 15(1), 35-56. https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/psicodidactica/article/view/733/608

Angulo, A., Caño, A. y Elorza, C. (2017). La igualdad de género en la educación primaria y ESO en el País Vasco. Instituto Vasco de Evaluación e Investigación Educativa. https://bit.ly/3klekDp

Aristizabal, P., Gómez-Pintado, A., Ugalde, A. I. y Lasarte, G. (2018). La mirada coeducativa en la formación del profesorado. Revista complutense de Educación, 29(1), 79-94. https://doi.org/10.5209/RCED.52031

Azorín, C.M. (2014). Actitudes del profesorado hacia la coeducación: claves para una educación inclusiva. Ensayos, Revista de la Facultad de Educación de Albacete, 29(2), 159-174. https://revista.uclm.es/index.php/ensayos/article/view/562

Ceballos, E. (2014). Coeducación en la familia: una cuestión pendiente para la mejora de la calidad de vida de las mujeres. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 17(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.17.1.198811

Drudy, S. (2008). Gender balance/gender bias: The teaching profession and the impact of feminisation. Gender and Education, 20(4), 309-323.http://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802190156

García, A. y De la Cruz, A. (2017). Coeducar para transformar: directrices educativas para combatir la violencia de género. UNES. Universidad, Escuelas y Sociedad, (2), 30-50. https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/revistaunes/article/view/12160

Gobierno Vasco. (2019). II Plan de coeducación para el sistema educativo vasco, en el camino hacia la igualdad y el buen trato (2019-2023). Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia /Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco. https://bit.ly/31LVOgZ

González-Barbera, C., Castro, M. y Lizasoain, L. (2012). Evaluación de las necesidades de formación continua de docentes no universitarios. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 5(2), 245-264. https://revistas.uam.es/riee/article/view/4319

Instituto Vasco de Estadística. (2019). Datos estadísticos de la C.A. de Euskadi. www.eustat.eus

Instituto Vasco de Evaluación e Investigación Educativa. (enero, 2013). Caracterización y buenas prácticas de los centros escolares de alto valor añadido. (Informe Final, Fase I 2012). Universidad del País Vasco/ISEI-IVEI/Gobierno Vasco. https://bit.ly/3obcxlf

Instituto Vasco de Evaluación e Investigación Educativa. (diciembre, 2015). La eficacia escolar en los centros del País Vasco. (Informe final 2011-2015). Universidad del País Vasco/ISEI-IVEI/Gobierno Vasco. https://bit.ly/3bU6SdN

Lizasoain, L. (2020). Criterios y modelos estadísticos de eficacia escolar. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 38(2), 311-327. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.417881

Macías, M. O. (2018). Las metodologías activas en la formación del profesorado del Grado de Educación Primaria: La resolución de problemas y la educación para la igualdad de género (coeducación). En E. López, C. R. García y M. Sánchez (Eds.) Buscando formas de enseñar: investigar para innovar en didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales (pp.347-355). Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=716952

Murillo, F. J. (2005). La investigación sobre eficacia escolar. Octaedro.

Nieto, P. (2019). La conciliación de la vida laboral y familiar de los hombres. ¿Cuál es la realidad? Ehquidad, Revista Internacional de Políticas de Bienestar y Trabajo Social, (11), 203-237. https://doi.org/10.15257/ehquidad.2019.0007

OCDE. (2019). TALIS 2018 Estudio internacional de la enseñanza y del aprendizaje, Informe español. Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/inee/evaluaciones-internacionales/talis/talis-2018.html

Pallarés, M. (2015). La cultura de género en la actualidad: actitudes del colectivo adolescente hacia la igualdad. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 19, 189‐209. https://revistas.uam.es/tendenciaspedagogicas/article/view/2008

Pena, M., Rey, L. y Extremera, N. (2012). Life satisfaction and engagement in elementary and primary educators: differences in emotional intelligence and gender. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 17(2), 341-358. https://ojs.ehu.eus/index.php/psicodidactica/article/view/1220

Quiñones, C. J. (2011). Paridad en la organización escolar: estudio metodológico de un procedimiento de medida. [Tesis doctoral]. Universidad de Sevilla, España.

Rausell, H. y Talavera, M. (2017). Dificultades de la coeducación en la formación del profesorado. Feminismo/s, (29), 329-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.14198/fem.2017.29.13

Rebollo, M. A., García, R., Piedra, J. y Vega, L. (2011). Diagnóstico de la cultura de género en educación: actitudes del profesorado hacia la igualdad. Revista de Educación, (355), 521-546. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3639425

Ugalde, A. I., Aristizabal, P., Garay, B. y Mendiguren, H. (2019). Coeducación: un reto para las escuelas del siglo XXI. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 34,16-36. http://doi.org/10.15366/tp2019.34.003

Valdés-Cuervo, A. A., Martínez-Ferrer, B. y Carlos-Martínez, E. A. (2018). El rol de las practicas docents en la prevención de la violencia escolar entre pares. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 23(1), 33–38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2017.05.006

Valdivielso, S., Ayuste, A., Rodriguez, M. C. y Vila, E. S. (13-16 de noviembre de 2016). Educación y género en la formación docente en un enfoque de equidad y democracia. XXXV Congreso SITE2016 Democracia y Educación en la Formación Docente. Vic, España. http://hdl.handle.net/10630/12421