Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 4, No. 1, 2002

"De nobis ipsis silemus?": Epistemology of Biographical-

Narrative Research in Education

Antonio Bolivar Botía

abolivar@ugr.es

Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación

Universidad de Granada

Campus Universitario de Cartuja s/n

18071

Granada, España

(Received: September 18, 2001;

accepted for publishing: February 7, 2002)

Abstract

The article analyzes how biographical-narrative research has currently become a perspective or specific approach in educational research, rather than just another qualitative methodology to be added to the rest. This type of research changes the usual concepts of what is considered knowledge in social science, and what is important to know. However, since modern times there has been a methodological deficiency in the justification of this type of research (validity, generalization and reliability). This study pulls together and describes the main lines of support for autobiographical accounts, critically analyzing the theoretical and epistemological disputes that have arisen in the last few years (positivism vs. hermeneutics, paradigmatic method vs. narration of data analysis). The paper also deals with the limitations and epistemological problems that arise from the defense of a strictly narrative data focus, and how this can be compatible with the paradigmatic ways of knowing.

Key words: Biographical-narrative research, epistemology, qualitative research.

Introduction

Kant headed the second edition of his Critique of Pure Reason with the motto given in the title (in the affirmative formulation). It was taken from Francis Bacon, and was a sign and guarantee of the work’s objectivity. Only when individuality is removed is science really being done. What has happened since then, that we consider that “we keep quiet about ourselves” should, paradoxically, be changed to “de nobis ipsis loquemur” (we talk about ourselves)? The positivist ideal was to establish a distance between researcher and object, correlating greater depersonalization with increase of objectivity. Narrative inquiry is simply a denial of that assumption, because the informants speak about themselves, without silencing their subjectivity.

The progressive exhaustion of positivism and the rehabilitation of hermeneutics, as their own modes of knowledge in social sciences, have changed the landscape. Dilthey, at the beginning of the last century, contributed decisively in giving their own epistemological status to the human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften), identifying the personal relationships lived by each individual as the key to hermeneutic interpretation. These lived experiences (erlebnis, which Ortega y Gasset translated as “experiences”) are the basis of understanding (verstehen) of human actions. The Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset, influenced by Dilthey, defending historical reason, noted–in his essay “History As a System–that “in opposition to pure physico-mathematic reason, there is, then, a narrative reason. To understand something human, personal or collective, it is necessary to tell a story.”

From phenomenology, Husserl (1991), in the thirties, made (The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology) a lucid analysis of how modern science (Galileo, Descartes) excluded the “world of life” (lebenswelt), by which is “made an abstraction of the subjects as persons with a personal life.” Many of the problems we dragged in to fit narrative research into traditional research comes from this separation introduced by modern science. Such exclusion –he argues– would not be justified in that the scientific/objective is based on lebenswelt (the world of life), prior and original base of all evidence. For this he suggests, instead of reducing it to scientific objectivity, “to take the world purely and in a totally exclusive manner just as the world has meaning and validity of existence in our life of consciousness [...], as subjectivity productive of validity” (p. 156).

Biographical research (from life-history), and especially, narrative (narrative inquiry), before the postmodern disappointment of the great narrations and the vindication of the personal subject in the social sciences, is each day acquiring greater relevance. As we have defended and explained at length in a recent book (Bolivar, Domingo and Fernandez, 2001) it entails a specific focus of inquiry with its own credibility and legitimacy to build knowledge in education. It demands, therefore, a distinctive mode of conventional qualitative paradigm, without limiting itself to a methodology of the collection and analysis of data. To that extent, it alters some suppositions of the settled modes of research, making of this practice something more accessible, natural or democratic. Having their own experiences and “reading” (in the sense of “interpreting”) of such deeds and actions, in light of the stories the actors tell, it becomes a peculiar perspective of research.

We attempt in this article the following objectives:

a) To stress the relevance and characterize narration in educational research, and especially, to induce the formation in this field of a community of researchers with this approach as a valuable means (alternative or complementary) of constructing knowledge in education.

b) To give an account of the current restructuring of the traditional epistemological categories and of what is meant by performing science, and what knowledge narrative research contributes as opposed to formal investigation.

c) To show the principal lines of epistemological foundation of the autobiographical stories, echoing the theoretical and epistemological disputes that have occurred in recent years.

d) To reaffirm their own (narrative) way of knowing, versus the established paradigmatic, leading to a strictly narrative analysis; becoming aware of the epistemological problems we debate today.

e) The theoretical principles of narration constitute, as noted, a specific way of investigating. We derive, then, the debate prior to its methodological implications: if the treatment of narration must be formal, or, rather, consistent with its specificity, singular.

I. The hermeneutic turn and the narrative in social sciences

Biographical and narrative research in education is established, then, within the “hermeneutic turn” produced in the seventies in the social sciences. From the positivist case it changed to an interpretative perspective, in which the meaning of the actors becomes the central focus of the investigation. The social phenomena (and, among them, education) will be understood as “texts”, whose value and meaning, primarily, are given by the self-interpretation that subjects relate in the first person, where the temporal and biographical dimension occupies a central position.

In this regard, the German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer has been the one who has best contributed to support the new ontology underlying epistemology. Thus, in some reflections on his great work Truth and Method (Gadamer, 1992), he stated that “human society lives in institutions that seem determined by the self-comprehension of the individuals who make up the society [...] There is no social reality, with all its their real pressures, which is not expressed in a linguistically-articulated consciousness” (pp. 232 and 237). Of similar type, rejecting the positivist treatment, Charles Taylor (1985) pointed out that we are essentially “self-interpreting animals”–animals that interpret themselves–i.e., there are no structures of meaning independent of their interpretation. This self-interpretation is undecipherable outside the narrative the individual produces biographically. This has seen, following the path opened up by Gadamer, Paul Ricoeur (1995), for whom the action is a text to interpret, and human time is built in a narrative way.

Coupled with our postmodern condition, we are, then, in a crisis of the established paradigmatic modes of knowing, where the role of the researcher/subject and the need to include subjectivity in the process of understanding reality are re-expressed. People’s narratives of people merge productively with the researcher’s narratives to understand social reality. The usual criteria (validity, generalization, reliability) of legitimation have begun to falter. Biographical-narrative research increases the crisis by introducing a rift between the experience lived and the way it should be represented in research discourse. There emerges, then, with all its force, the dynamic materiality of the subject and his1 personal dimensions (affective, emotional and biographical), which can only be expressed by biographical narratives in social sciences (Chamberlayne, Bornat and Wengraf, 2000). In turn, the growth and popularity reached by narrative inquiry about the life stories and biographies of those involved in education (Goodson and Sikes, 2001) reflect–as has been lucidly pointed out by Hargreaves (1986)–our current postmodern situation, where the only refuge left is the self.

We understand as narrative, the structured quality of experience understood and seen as a story; or else (as a research focus), guidelines and forms of constructing meaning, based on temporal personal actions, by means of the description and biographical analysis of the data. It is a particular reconstruction of the experience, by which, through a reflective process, meaning is given to what happened or was lived (Ricoeur, 1995). Plot, time sequence, characters, situation, are ingredients of the narrative configuration (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000). To narrativize life in a self story is–as Bruner and Ricoeur say–a way of inventing one's self, of giving oneself an identity (narrative). In its highest expression (autobiography) it is also the production of the ethical project of what the life has been and will be (Bolivar, 1999).

Moreover, biographical research has a long tradition in Latin America, especially in Mexico. After its employment in the thirties by the so-called Chicago School, Oscar Lewis (1966) wrote, at the beginning of the sixties, the familiar story of Mexico’s Sanchez family, who made a strong impact (published in English in 1961, and translated in the following years into French and Italian), coinciding with the crisis of the Quantitative Methods in Sociology. The interwoven stories of the various members of the family (father and four children) provided a practical example of making another kind of history.

II. Hermeneutic-narrative research versus traditional-positivist

Biographical and narrative research in education, rather than the scientific method prevailing today, require other criteria, going beyond the contrast established between objectivity and subjectivity, and based on evidence originating in the world of life. As a mode of knowledge, the story captures the richness and detail of the meanings in human affairs (motivations, feelings, desires or purposes) that cannot be expressed in definitions, factual statements or abstract propositions, the way logical-formal reasoning expresses things. “The object of the narrative,”–says Bruner (1988, p. 27) is the vicissitudes of human intentions.”

The peak of hermeneutic turn, parallel to the fall of positivism and the aspiration to give a “scientific” explanation for human actions, has led us to understand social phenomena (and teaching) as “text”, whose value and meaning is given by the hermeneutic self-interpretation which the actors offer for it. Instead of trying to provide an explanation of the teaching, breaking it down into discrete variables or establishing indicators of efficiency, it is understood that the significance of the actors should be the central focus of attention. The great universal and abstract principles, by their generalization, distort the understanding of the concrete and particular actions. A hermeneutic-narrative, by contrast, allows the understanding of the psychological complexity of the narratives that individuals make out of the conflicts and dilemmas in their lives.

However, with the rationalism of modern science, there has been imposed, as a kind of justified rationality, a type of discourse that proceeds by hypothesis, evidence and conclusions, following the laws of logic or of induction; and relegates to the subjective realm the entire dimension of the expression of experiences. This conventional type of research not only fails when it addresses life experiences, but rejects these as a possible object of research, upon entering the realm of the subjective, which should be excluded from scientific research (Van Manen, 1990). The basic assumption of departure of this type of rationality–as Kant said in the motto mentioned in the title of this paper–is that the less subjective and more objective something is, the greater the degree of its scientific nature. Hermeneutic research, in contrast, aims to give meaning and to understand (as opposed to “explain” cause/effect relationships) the experience lived and narrated.

The sense of an action–what makes it intelligible–can come only from the narrative explanation given by the agent concerning the short-term intentions, motives and purposes she has for it, and more broadly how it fits into the horizon of her life. Van Manen himself (1994, p. 159) has reported:

The current interest in stories and narrative can be seen as the expression of a critical attitude toward knowledge and technical rationality, and scientific formalism, and toward knowledge and information. Interest in the narrative expresses the desire to return to meaningful experiences we encounter in everyday life, not as a rejection of science, but rather as a method that can address concerns that normally are excluded by normal science. [...] The meaning of the expansion of narrative methodology in North American educational research is probably not so much a new methodology as a form of humanized scientific research, expressed in narrative and biography.

Breaking decidedly with a concept of instrumental rationality or technology of education, in which education is a means to achieve specific results, the narrative is addressed to the contextual, specific and complex nature of the educational processes. The judgment of the teacher matters in this process, which always includes, besides the technical aspects, the moral, emotional and political dimensions.

Coming from the psychological field, Polkinghorne (1988) has made a good history of psychological narratives, asserting that narrative is “the primary way in which meaning is given to human experience.”2 Similarly, Hunter McEwan (1997) says that narrative is “the proper form for characterizing human actions”. In this context, life stories acquire a great relevance, both as objects of research and as methodology (Goodson and Sikes, 2001), in which is reflectively and explicitly stated a chronicle of the self in the social geography and time of the life. As a heuristic use of reflectiveness, the informing subject becomes a co-researcher of his own life.

On the other hand, there has been vindicated for women, their own way of knowing, different from logical-formal, androcentric reasoning (belonging to an epistemic self”), which leads the narrative to be considered as a specific form of female discourse. It Includes the “voice” and assumes the status of author in the discourse of research (expressed in first person singular), equivalent to a “dialogical” self that feels and loves, as opposed to the dominant mode of discourse about teaching (rationalist or supposedly neutral report, typical of an alien asexual, i.e. angelic one). Orality had, since its first use (e.g. in oral history) a militant vocation of giving voice to “silenced lives” (McLaughlin & Tierney, 1993), among which would be those of women. The life stories of female teachers are providing a new way of understanding the teaching profession, in which the personal and professional are brought together (Weiler and Middleton, 1999).

The story is thus a way of understanding and expressing life, in which the author's voice is present. Because of the educational activity, it is a practical action that occurs in specific situations, guided by certain intentions, it seems–as teachers show when they tell us about their classes–that stories and the narrative are a way, at least as valid as the paradigmatic, of understanding and expressing teaching. In this sense, Elbaz (1991, p. 3) emphasizes that:

Narrative is the very stuff of teaching, the landscape in which we live as teachers or researchers, and within which the meaning of teachers’ work can be appreciated. This is not just a claim concerning the emotional or aesthetic side of the notion of story, in keeping with an intuitive understanding of teaching; it is, on the contrary, an epistemological proposal, that the knowledge of teachers is expressed in their own terms by narrations, and can be best understood in this way.

If explanation is the mode of becoming aware of natural phenomena (Von Wright, 1979) establishing constant connections between its elements, then understanding would be the mode of becoming aware of human actions from the intentions which give them meaning. Neither methodological monism nor dualism would take us back to a situation already overcome. To the extent that the explanatory procedures in the social sciences are homogeneous with the science of nature, there is continuity in the scientific field. But equally, understanding contributes, in the knowledge of actions or human institutions, a specific component that is irreducible to causal explanation. Therefore, it is fairer to express it in dialectical terms: “the necessary mediation of comprehension through explanation” (Ricoeur, 1977, p.131) and, alternatively, of the latter by the former.

III. Two Modes of scientific knowledge: Paradigmatic vs. Narrative

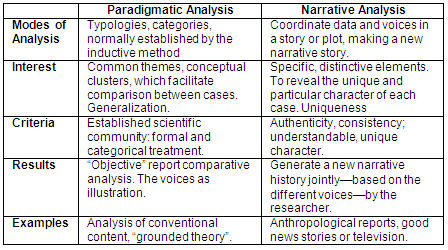

Jerome Bruner has been one of the researchers who has contributed most to giving epistemological status to the narrative mode of knowledge and reasoning. His work Two modes of thought, collected in Bruner (1988, pp. 23-53), meant, in its time, the eruption in the psychological and educational world of the narrative program, as well as an initial and excellent legitimation. In it, Bruner speaks of “two ways of knowing and thinking,” each with its own distinctive forms of organizing experience, constructing reality and understanding the world; its universality, in all cultures, suggests they may be based on the human genome: but if we do not want to be innativists, it could well be said–as generativists–that they are given by the very nature of language (Bruner, 1997): they have different cognitive functions, represent two forms of understanding reality, are not reducible one to the other, and more relevant, the forms for judging validity also differ (Table 1).

The Paradigmatic Mode of knowing and thinking, according to the inherited logical-scientific tradition, is expressed in a propositional knowledge standardized by rules, maxims or prescriptive principles. This Paradigmatic Mode is not strictly identified with classical positivism, although it comprehends it.

Table I. Two forms of scientific knowledge in the study of human action, according to Bruner

In contrast, the second, emerging, is the Narrative Mode (sintagmatic), characterized by presenting concrete human experience as a description of the intentions, through a sequence of events in times and places, in which the biographical-narrative stories are the privileged means of knowledge and research (Huberman, Thompson, and Weiland, 2000).

If in the first there are shared procedures of rationality and verification, the Narrative Mode is qualitatively different in centering on feelings, experiences and actions depending on specific contexts. This narrative knowledge is another legitimate way of constructing knowledge, which should not be confined to the realm of emotional expressions:

The two Modes (though complementary) are irreducible one to the other. Attempts to reduce one mode to the other or to ignore one at the expense of the other inevitably cause the loss of the rich diversity contained in thinking. Moreover, these two ways of knowing have their own functional principles and their own criteria of correctness. They differ primarily in their procedures of verification (Bruner, 1988, p. 23).

Thus, contrasted with a logical way of arguing, the narrative mode of knowledge is based on the fact that human actions are unique and not repeatable, and addresses their distinctive characteristics. Its wealth of nuances cannot then be exhibited in definitions, categories or abstract propositions. If paradigmatic thinking is expressed in concepts, the narrative does it through anecdotal descriptions of particular incidents in the form of stories that allow us to understand how human beings make sense of what they do. By the same token, they should not, at the risk of strangling them, be reduced to a set of abstract or general categories that annul their singularity.

Similarly, Polkinghorne (1988, p.159) contrasts the narrative knowledge of the humanities with the knowledge of the physical or natural sciences. The first “do not produce knowledge that leads to the prediction and control of human experience, but instead, they generate knowledge that deepens and enhances the understanding of human experience.” This knowledge organizes events into integrated units of meaning; the events are arranged in sequence, instead of categories. Narrative knowledge is more concerned with human intentions and meanings than with discrete facts; more with the coherence of logic and understanding than with prediction and control.

Continuing now with the fine analysis of Polkinghorne (1995), the paradigmatic mode of knowledge is characterized by classifying individuals and stories under a concept or category (a set of common attributes shared by individuals). In all these cases, it has to do with establishing to which each of the individual instances belongs; of including the particular in the formal (category or concept), annulling any individual difference that ought to be classifiable. The paradigmatic mode is fixed, especially, on the attributes that define the individual items as instances of a category, and not in that which differentiates one member from other members of a category.

From this perspective, it is important to note that paradigmatic reasoning is common in quantitative and qualitative research designs. In quantitative designs, the categories are pre-selected before the collection of the data (e.g., a questionnaire), so that it is determined in advance which dimensions or events are instances of a category of interest, as well as to what degree or level they satisfy it. Certain quantitative techniques (e.g., factorial or “cluster analysis:) allow them to be grouped into common factors.

By contrast, in qualitative designs, the emphasis is on the construction or inductive generation of categories that would permit the contribution of a categorical identity and classification of the collected data, which are examined according to significant nuclei, in codification frameworks that serve to separate data by groups of similar categories. Through an analytical process, data are broken down, conceptualized, grouped and integrated into categories as in Glaser and Strauss’s analysis of “grounded theory” (1967). Most qualitative analyses consist of a resourceful process between the data and the emergence of categorical definitions, through a process that produces classifications, organizing the data according to a specified and selective set of common dimensions. Thus, they do not differ in this aspect from the so-called quantitative analysis, only now the categories are not predetermined; they are induced or emerge from the data.

What belongs, then, to the paradigmatic way of thinking, which includes–as we have just seen–the analysis known as qualitative, is to organize experience in such a way as to produce a network of concepts which group together the common elements by categories with some degree of abstraction. The knowledge is decontextualized so that it can unify the uniqueness and diversity of each experience. It is curious that we tend to catalog as “qualitative” a research by the manner in which it collects data (field notes of participational observation, interviews, etc.), when what makes it qualitative should be, rather, as “grounded theory” emphasized, the way things are analyzed and “represented”, that is to say, a different way of causing theory to emerge.

This is evident in thematic analysis of content by categories: speech is discourse is broken up into subcategories, grouped taxonomically in the subheadings of each category (or its grouping: metacategory); the grid of categories is applied in the same manner to each interview, which allows them to be treated quantitatively, and even attempts to find causal relationships between categories. To do this, it is limited to the discourse contents, disdaining the very way of expressing them and their subjective meaning. “Thematic Analysis is based on the destruction of the structure of the unique speeches”, said Demazière Dunbar (1997, p. 19) in a good critique of this type of analysis.

On the contrary, as we will see next, narrative reasoning works by means of a collection of individual cases that go from one to another, and not from a case to a generalization. The concern is not to identify each case under a general category; the knowledge proceeds by analogy, where an individual may or may not be similar to others. What matters are the worlds lived by the interviewees, the unique senses they express and the particular logic of argument they deploy.

IV. Two types of narrative research in education

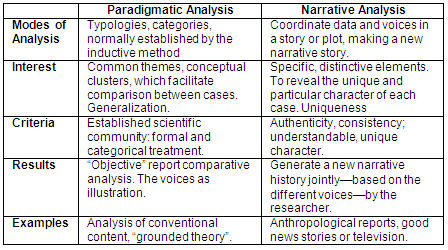

We are now in condition, according to the foregoing reasoning, and closely following Polkinghorne (1995) and Bruner (1988), to distinguish two types of narrative research (Table 2). While both are legitimate forms of constructing knowledge in educational research, each has distinctive forms of generating knowledge and specific validation and reliability criteria, so that research reports done according to one mode cannot be verified according to the other.

a) Paradigmatic analysis of narrative data: studies based on narratives, oral history or life, but whose analysis (normally called “qualitative”) proceeds by paradigmatic typologies, taxonomies or categories, to arrive at certain generalizations of the group studied.

This has been the predominating manner of qualitative research: the data obtained are examined according to general and common patterns. From a temporal point of view, data can be clarified either diachronically or synchronously. Diachronically, the data contains temporal information about the sequential relationship between the events; they describe when an event occurred and the effects it had on what followed. Thus, in autobiographical organization, there are included references to when and why certain actions had such and such results or impacts. In synchronous organization, they are framed as categorical answers to the researcher’s questions.

The paradigmatic mode of data analysis usually consists of looking for common themes or conceptual groupings in a set of narrations collected as a data or field base. Two types of paradigmatic analyses are usually made:

The concepts are derived from the previous theory, and are applied to determine how each of the particular instances are grouped under the grid of categories.

Another, where in place of the research’s imposing the data concepts derived theoretically, the categories are derived inductively from the data, which have been the most extensive in so-called qualitative research.

The “grounded theory” of Glasser and Strauss (1967) provides a good illustration: inductive analysis consists of a recursive movement of the particular data, which we consider similar, to successive categories proposed by the investigator for grouping them. Grouping the raw material into categories are tasks of analysis, and it may take a succession of category reformulations for the data to be best fitted into the categories. Then, an attempt is made to find relationships between categories, using matrixes. In any case, there is always an attempt, according to paradigmatic procedures, to generate general knowledge (grounded theory) from of a set of particular histories. Knowledge, in order to be valid, must be abstract and formal, scorning the singular and unique aspects of each story. As for the well-known manual of Miles and Huberman (1984) on the Analysis of Qualitative Data, at bottom, in order to make qualitative research credible (need felt at the time), it imposes a “rigorous” treatment (i.e. paradigmatic or quantitative) on categorical narrative data.

More clearly, as we mentioned earlier, all the thematic analyses of interviews, according to taxonomies of categories, have the same basic logic as the questionnaire: quantitative treatment of qualitative material that later–so as not to despise it–is used for illustrative purposes, quotations selected from the interviews, which support what the quantitative analysis has previously determined.

Table II. Contrast between two types of narrative data analysis

b) Narrative Analysis, strictly speaking: studies based on particular cases (actions and events) but whose analysis (narrative, in the strict sense) produces the narrative of a plot or argument, through a narrative story that makes the data meaningful. Here we do not seek common elements, but unique elements that make up the story.

In contrast with the previous paradigmatic mode, the result of an analysis of narratives is, at the same time, a particular narration, without trying to generalize; for example, a historical report, a case study, a life story, an episode narrated from the life of a particular person. The researcher's task in this type of analysis, is to configure the data elements in a story that unites and gives meaning to the data, to an authentic mode of expression of individual life, with the aim of expressing the individual life in an authentic manner, without manipulating the voice of the participants. The analysis requires the researcher to develop a plot or argument that will allow him to unify the elements temporally and thematially, giving a comprehensive answer to why something happened. The data can come from very diverse sources, but the things is for them to be integrated and interpreted in a narrative intrigue. The ultimate goal is, in this case, unlike the paradigmatic way, to reveal the unique character of an individual case and to provide an understanding of its particular complexity or idiosyncrasy.

Thus, if under the umbrella of “qualitative research” one can speak of “narrative inquiry,” what we have wanted to show is that we must distinguish two types, consistent with Bruner’s (1988) Modes of Knowledge. In both types, one works with narrative data, and they contribute in a relevant manner to the generation of social knowledge. However, as we have just shown, the way they do this and the forms of representing the data in the research reports differ greatly.

Nevertheless, Polkinghorne’s (1995) distinction is not always pertinent, especially if it is understood as a dichotomous choice: an investigation is an “analysis of narrative data” or a “narrative analysis”. As noted by Elbaz (1997), there may be in the investigation, legitimate interests which are not covered by just one “narrative analysis”. Thus, to investigate the general professional trajectory of the teachers of an educational level, it may be suitable for us to recount a good number of life stories, requiring, by their own extension, some sort of data analysis (categorical, structural or of another type); but at the same time, we may be interested in reconstructing certain particular stories narratively.

V. Data Analysis: between categorization and narrative

Working with biographies sharply updates the intrinsic dilemma of social science research. The source material, the life story of the persons, is so multiple but at the same time so unique that we have the impression of deteriorating it from the very moment we put our descriptive and analytical hands on that material.

Huberman (1998, p. 225)

Let us, then, set down some of the serious epistemological problems that cause us to defend an autonomous or self-analysis of the narratives, as Michael Huberman expresses in the previous text. Entering this dimension, in essence, reproduces, in its way, the old debate of anthropological research, between an emic and etic mode of proceeding, between descriptions from within (first person, phenomenological) versus descriptions from outside (third person, objectivist).

First, it is evident that narrative inquiry, whose result is a narrative report. Has the advantage of not violating or expropriating the voices of the subjects investigated, in that it does not impose categorical analyses of their words. The problem generated is that, if the teachers’ emic discourse is excessively respected, the interpretation gets caught inside the horizons of the interpreted (as would be the ethnography of the Trobiand Islanders created by themselves), precluding any comparative generalizable, or theoretical explanation which makes superfluous any task of analysis. Precisely, the greatness of the anthropology of the Trobiand Islanders by Malinowski (1973) lies in his having given us a reconstruction of their life and thought through his not being involved in their world.

Under the motto the rejection of generalizations and possible distortions by teachers’ or students’ narratives, the emic discourse of these cannot be sanctified. At the end of the day, the teachers’ stories themselves are social constructs that give a particular meaning to facts, and as such, should be analyzed by the investigation. As Huberman says, in educational research it seems legitimate to look for common themes and significance in the teachers’ unique biographies which would lead to possible explanations of why they say what they say. In fact, this is what social scientists have claimed. Within the relevant specifications, we defend this, because for these stories to be relevant to the purposes of the investigation, they should also be subject to certain paradigmatic modes accepted for analyzing information.

In a voluminous report on world poverty, Pierre Bourdieu and his team (1999) favor oral testimony, refusing to do any type of analysis (categorical or not) of the ample biographical-narrative material collected; they only organize and give titles to the transcription of the 182 interviews in a coherent manner. Thus, they report at the beginning: “We here deliver the testimony that men and women gave to us regarding their existence and the difficulty of living. We organize and present them with the aim of getting the reader to give them a look as comprehensive as that which they impose upon us and which permit us to grant them the demands of the scientific method.”

The main argument for this posture is to “give the means of understanding; that is, to take the words of the people as they are”, leaving to the reader–in a kind of “democratization of the hermeneutic position”–the task of analysis and understanding. Only at the end of the book is there a section (entitled “Understanding”) devoted to expressing some of epistemological presuppositions with which they have operated in the investigation. Case studies are, thus, short stories of the people, properly in tune with the theme or life situation.

The reactions it has provoked–some have dared to accuse the work of being “miserable sociology”, or have said that it contradicts the way in which Bourdieu himself had previously worked–show the crisis in methodology and in how to represent the words of the people with whom we met. A formalist or strongly categorical analysis fragments the discourse into codifiable elements, de-contectualizing it. But an extreme “fidelity” to the discourse itself would limit the analysis to providing another narrative of the information collected, except that now the discourse is strung together. The relationships between who reports and who analyzes the information, cannot be limited to “taking note of something”. The task is, on the one hand, to decipher meaningfully the components and relevant dimensions of the lives of the subjects, and on the other, to situate the narrative stories in a context that will contribute to providing a structure in which they will have a broader application. For the stories to be relevant to the purposes of the study, they must be reconstructed according to certain paradigmatic modes accepted for analyzing information.

The French work of Demazière and Dunbar (1997), How to Analyze Biographical Interviews, is also exemplary of this grave methodological deficit concerning how to analyze biographical interviews, which are narrative discourse. In it, while making a critique based on conventional methods of analysis, when they come to propose a Barthes-type structural analysis as an alternative for stories, it seems to us a definite way out. They reject as insufficient, both an illustrative posture limited to making a selective use of the interviewees’ words in the service of what the researcher wants to show; and a hyper-realistic stance that attempts to assign all the value to the actual words of the interviewees, as if the words themselves were transparent. Instead, they defend an analytical way of approaching the interviews, with a theory generated from data analysis, and determined by a structural analysis of the biographical accounts. In this sense, they think that the different techniques of content analysis are inadequate for analyzing the biographical interviews.

VI. How did we turn out?

We have noticed the tendency in social science to “prune” the recorded voices of the actors, according to the taste of the researcher, manipulating the original discourse. Currently, the matter lies in striking a balance between an interpretation that is not limited, from within, to the interviewees’ discourses; nor to an interpretation, from the outside, which would dispense with the nuances and modulations of the discourse narrated. Overcoming the mere collage of text fragments mixed ad hoc implies that the researcher should penetrate the complex set of symbols that people use to give meaning to their world and life, achieving a sufficiently-rich description in which they would acquire meaning.

The final question is what status should be given to people’s words, or in other terms, whether the biographical is complementary or should have autonomy; in any case, how to represent the voices at a juncture of crisis in the representation. These do not reflect reality in themselves; they discursively construct a world lived by the actors. The interview obeys specific rules of the production of meaning. Sustainable today are neither the illustrative postures (extracts from the interview, cited to illustrate what is said, a “selective appropriation”), nor in the extreme case, radical textualism (giving great place to the word of the interviewees, restoring the words as if they said it all.

Meanwhile, categorical analysis (with all the variants, including computer programs, of content analysis) as a fence-straddling way out, has led to some disappointment, because we are not facing informative texts, but biographical narratives that humanly (by feeling, thinking, acting) construct a reality. It has been little noticed that the empirical analysis of categorical content initially emerged (Berelson, 1952) for the treatment of informational or journalistic texts, in which the personal-emotional dimension is absent. Hence, their application to texts that do not describe events, but reconstruct a world/life in the discourse itself is always deficient. The nuances of the narrativization of a life can never be caught in a thematic category. Demazière and Dunbar (1997, p. 94) even claim that, in the case of narrative interviews, “the different techniques of content analysis are inadequate for the analysis we want to accomplish regarding the meanings.” However, it is appropriate to combine qualitative analysis and hermeneutic analysis in fruitful conjunction, even when an equilibrium would be unstable, ready to break at one end. Maintaining educational research as a scientific enterprise implies not giving up some paradigmatic forms.

Then, in narrative research one must practice a kind of binocular vision, a “double description”. On the one hand, there is needed a portrait of the informant’s inner reality; on the other, this must be inscribed in an external context that provides meaning and sense for the reality experienced by the informant. The reported experiences of discourse must be situated within a set of regularities and patterns explainable socio-historically, thinking that the story of life corresponds to a socially-constructed reality. However, one cannot disparage the fact that it is completely unique and singular.

The issue is, as Eisner (1997) has expressed, on the one hand, that it should be taken as research, and on the other, whether research must be assimilated into the established scientific modes. We can sign in, as we do, on the first part without being fully in accord with the second. In the situation today, we can maintain that a good (realistic) novel can contribute a level of knowledge of a reality that quantitative research could already claim. But as educational research, it must have with it a format of narrative argument, and must rest–with some degree of systematization–on data. The form of presentation does not determine the research, but the way in which it is argued and justified. There would be countless examples (from the Platonic Dialogues) to show that the degree of human understanding of phenomena does not belong exclusively to a formalized representation.

With the specifications given above, we advocate that these stories should be relevant to the purposes of research and subject to certain accepted paradigmatic modes of analyzing information. A “radical textualism,” excluding all types of paradigmatic analysis, presents a break with the academic modes of research. At this juncture, for now, a framework of intelligibility of the stories must combine those elements just as they were said in the emic description, while not relinquishing the production of interpretive descriptions that would go beyond the horizons of the interpreted. As Geertz has written (1994, p. 22), what it is about, is “reorganizing the categories in such a way that they can be disseminated beyond the contexts in which they were born and originally acquired sense, for the purpose of finding affinities and reporting differences.”

VII. The Narrative report

In producing a biographical-narrative report we found ourselves caught between not wanting to violate or expropriate the voices of the subjects investigated, imposing categorical analyses distant from the subjects’ words; and submitting them to formal tenets that would induce us to explain why they say what they say. The process of a narrative analysis, then, is to synthesize an aggregate of data into a coherent whole, in place of separating them into categories. The result of this integration an understanding of the past events in retrospect, according to an unbroken temporal sequence, to reach a certain end. Here the recursive process moves from the data to the emergence of a specific plot. This plot determines which data should be included, in what order, and with what purpose.

The report is a story that the researcher/writer first tells himself, other significant persons, and, above all, the reading public. Narrative research is a process, complex and reflective of the mutation of the field texts into texts for the reader. The researcher recreates the texts so that the reader can “experience” the lives and events narrated. The speeches collected in the field are then transformed into public documents, according to the changing guidelines ordinarily reigning in the scientific community in question.

The result is not, then, a cold and neutral, objective report, in which the voices (of the protagonists, researcher and researched) are silenced, nor is it a mere transcription of data; it consists in having given meaning to the data and having represented the meaning in the context where it occurred, in a task closest to a good news story or a historical novel. At the end of the day, as some might adduce, this form of analysis means neither arbitrariness nor mere literature. In literary analyses themselves, we can distinguish good and bad analyses. What it does mean is to bring them closer to the strictly qualitative, as for the rest Geertz (1989, p.19) has said about anthropology: “It is evident that, things being what they are, anthropology is closer to the ‘literary’ discourses than to the ‘scientific’.

The researcher becomes the one who constructs and tells the history (researcher-storyteller) by means of a story, which often lets the voice be heard. But to the extent that the story wants to be realistic, the researcher should include evidence and arguments that support the plausibility of the narrative offered. Although there may be several arrangements of the data, the best report is that which achieves a greater authenticity and consistency. The classic examples can be certain of Freud’s analyses of case studies, studies of the symbolic interactionists of the Chicago School, the reports of anthropologists on other peoples, and so on.

A good narrative research is not just one that collects well the different voices in the field, or interprets them, but also is that which gives rise to good narrative history, that is, at bottom, the research report. From this perspective, what is called “explanation” in conventional research would be nothing but the best way to organize a story to make it understandable and convincing. The unique biography must be written within a framework of general structure; the narrative of action, in a genealogy of context that explains it. As Geertz (1994, p. 89) has said of ethnography, it must achieve “a continuous dialectical balance between the most local of local detail, and the most overall of the overall structure in such a way that we can formulate a simultaneous concept...situate both parties in a context where they explain each other mutually.”

The narrative report of an investigation should be, itself, narrative. As noted by Zeller (1998, p. 296), “paradoxically, although many researchers in the humanities have rejected a positivist concept of objectivity in the methodology of investigation, they have not rejected its influence on the style of writing”, very conventionally glued to the established modes. For that, he proposed that in the form of presentation, much could be learned from the new ethnography, from the new journalism, and from the creative tales of fiction and nonfiction (e.g., novels of social realism). Thus, the narrative strategies employed by the most innovative journalists can serve as a model for the drafting of case reports.

The grave problem of the exclusive defense of a narrative analysis, is that in wanting to grant epistemological status to the personal narrative, we can lose some minimal criteria, shared by the community of social scientists, on what should be taken as knowledge. In a beautiful analogy, Kushner and Norris (1980) said that academia dedicates itself to caring for the gardens of the truth, pointing out the flowers that must grow. Since the Discourse on the Method of Descartes, the two modes of analysis have been separated, giving scientific status only to the first. It seems clear that, as McEwan says (1998, pp. 237-7), “the majority of academic writing can be considered as an effort to stifle the urge to tell a story; and at the same time, the guidelines of academic composition tend to promote non-narrative writings above direct stories... [according to] the scientific ideal of objectivity which identifies objectivity with the distance between the scientist and his object of study.”

And so it is that, in this ending of modernity, the full assumption of the relevance of the teachers’ (auto) biographical stories in the habitual practices of research, implies reorienting these settled, conventional fieldwork practices, to admit turbulent waters that bring these modes into question. This is our problem. As we mentioned in the beginning, a few years ago Elliot Eisner (Eisner et al., 1996), in a presidential address given to the annual convention of the American Educational Research Association, discussed whether a doctoral thesis written in the form of a novel should be admitted as research. The question itself is already a sign that the established paradigm is beginning to flounder. Are we, then, in a “post-paradigmatic” period?

VIII. Are the two modes compatible in educational research?

Epistemologically, what in fact is being debated, is the question of two postures:

1. Compatibility Thesis: Considers that both types of knowledge are legitimate and complementary, but irreductible, as Bruner argues (1988).

In this first position, for example, Huberman (1998) maintains that, paradigmatically, we can, as he has done, apply methods of description and analysis by means of which our theories come to correspond more closely with archetypes or prototypes that underlie the richer narratives: “These are the elements that constitute great literature, foundational studies in social anthropology, and the best social theory we have,” he comments (p. 226). To come to these theories to analyze and interpret narrative data has been the basis of the paradigmatic mode of scientific knowledge, which does not exclude the possibility of reformulating the theories when they do not fit with the data. However, sensitive to our current situation and as a sample (reluctant) of the theory of compatibility, he writes: “I maintain that we can feel these archetypes intuitively and that we can also demonstrate them systematically and even scientifically,” and even to qualify them as basically unscientific is a cultural bias of our rationalist civilization.

2. Thesis of incompatibility: Paradoxically it can be defended from one side (the scientific-paradigmatic) or from the other (the narrative). Thus, from the former:

a) Only conventional scientific research, practiced in the paradigmatic mode (either quantitative or qualitative), produces scientific knowledge, so that the “analysis of narratives” cannot be admitted into scientific knowledge, but can only be relegated to the realm of practical reasoning.

This is the thesis defended by Fenstermacher (1994b), distinguishing two types of discourse, belonging to each class of research:

1) Practical discourse: expresses the language of action and human activity, normally by means of intentions, desires, frustrations, aspirations, etc. It refers to the context in which teachers work, and as such, is specific, situational and particular. Expressed orally, more than by discursive reasoning.

2) Research discourse: a technical discourse, abstract, relating to methods of research, in which are excluded, by principle, valorative considerations. Normally it is highly structured and is produced according to the scientific community’s tradition of research (whether quantitative or qualitative).

Because there is no cognitive isomorphism between the two fields, we can only defend two sciences in the study of teaching, so that we can think in terms of two different discourses on educational research. Each discourse can potentially generate knowledge, but practical knowledge is justified in terms of “good reasons”, according to the patterns of the ethical and moral plane (Fenstermacher and Richardson, 1994), in this situation, supported by two sciences in the educational field: conventional science and narrative or interpretive science.

As we protested elsewhere (Bolivar, 1995), this means, first, taking refuge in a traditional position in which, being obliged to accept the research and the knowledge produced from the interpretive angle, “good” science continues to be the conventional or paradigmatic. Second, it remains a positivist posture, since it silences the contemporary debate over “understanding versus explanation”, in which, with hermeneutics, the social sciences acquire the status of independence of their progressive positivist naturalization. Forced to acknowledge the existence of practical research or narrative, it comes to warn: we must not be confused, true science is that which is conventionally established, there is another research (practice) that does not attain that status.

Because of this, we believe that, more than moving educational theory from the field of theoretical reason to that of practical reason (Fenstermacher, 1994b), the question would be to delimit in what measure its specificity inevitably moves between the two. It does not have to do with relegating the knowledge of teaching to an “autonomy of practice”, conceding to it its own epistemological status at the cost of stealing the common criteria of scientific rationality so as to situate it in the ethical-moral field. This operation would not take us very far from what we are attempting. When you get right down to it, it is a strategy inherited from positivism.

Contrary to the former, thesis [b] maintains that:

b) Scientific formalism or technical rationality is incapable of understanding the inner qualities that define teaching. Precisely the current interest in narrative comes to be the expression of a critical attitude [a], by leaving out the significant experiences of daily life (Van Manen, 1994). The form of narrative reasoning contrasts with logical reasoning, both in the premises and conclusions and in the very manner of expression.

In a discussion of the theme with Van Manen, Fenstermacher (1994a), somewhat skeptically, says that–according to the current state of the question–to decide between [a] or [b] is an expression of a preference (prejudice, interest or ideology). In a debatable manner he maintains that the narrative, in itself, lacks strong and vigorous tenets of reasoning and rationality (which are provided only by the paradigmatic tradition); and that limiting it to is own tenets impedes the ability to clarify when the account of an experience expresses a false perception or misinterpretation.

Instead, we can sustain that narrative research allows one to represent a set of dimensions of experience that formal investigation leaves out, without being able to note relevant aspects (feelings, intentions, desires, etc.). Our current position is that this should not mean rejecting generally-recognized tenets of reasoning and justification. We must situate narrated experiences in discourse within a set of socio-historically explainable regularities and guidelines, thinking that the life story corresponds to a socially constructed reality. However, we must not fail to appreciate the fact that it is completely unique and extraordinary. In short, we are facing the previously-mentioned dilemma of combining a point of view of the native (emic) and the researcher (etic). In many cases, the roles of knower and known change, or, better, stop being differentiated, so as to come together, breaking with what has been an untouchable principle of cognitive objectivity. As we have pointed out, today, at our postmodern juncture, the matter of writing the biographical-narrative research report is in play between not making the stories sacred, and not assimilating them into the traditional paradigmatic modes of knowing, where they would fit in vain.

Putting oneself in place of the other and empathizing with her life and feelings can, in effect, increase understanding (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000); but at the same time, it impedes seeing the context in which it acquires a broader sense. If in the postmodern era the personal is the political, according to our enlightened modern heritage, it is necessary to place them in a genealogy of context, as Goodson (1996) has claimed. This would lead the teachers themselves to realize (and act in) these other dimensions that determine their work in the classroom, since, after all, they may not be the authors of their own song. As noted by Dentin (1989, p. 74): “at times a person acts as if he made his own history, when, in fact, he is forced to make the history he claims to have lived.” The versions that teachers and professors construct of themselves in their narratives are social constructions, that should not be turned into just a thing.

References

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press.

Bolívar, A. (1995). El conocimiento de la enseñanza. Epistemología de la investigación curricular. Granada: Force. Universidad de Granada.

Bolívar, A. (1999). Enfoque narrativo versus explicativo del desarrollo moral. In E. Pérez-Delgado & M. V. Mestre (Cords.), Psicología moral y crecimiento personal. Su situación en el cambio de siglo (pp. 85-101). Barcelona: Ariel.

Bolívar, A., Domingo, J. & Fernández, M. (2001). La investigación biográfico-narrativa en educación. Enfoque y metodología. Madrid: La Muralla.

Bourdieu, P. (Dir.). (1999). La miseria del mundo. Madrid: Akal.

Bruner, J. (1988). Realidad mental, mundos posibles. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Bruner, J. (1997). La educación, puerta de la cultura. Madrid: Visor.

Carter, K. (1993). The place of story in the study of teaching and teacher education. Educational Researcher, 22 (1), 5-12 and 18.

Clandinin, J. & Connelly, M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Chamberlayne,.P., Bornat, J. & Wengraf, T. (Eds.). (2000). The turn to biographical methods in social science. Comparative issues and exemples. London/New York: Routledge.

Demazière, D. & Dubar, C. (1997). Analyser les entretiens biographiques. Paris: Nathan.

Denzin, N. (1989). Interpretative Biography. Newbury Park, CA.: Sage.

Eisner, E. (1997). The promise and perils of alternative forms of data representation. Educational Researcher, 26 (6), 4-10.

Eisner, E., Gardner, H., Saks, A., Donmoyer, R., Stotsky, S., Wasley, P., Tillman, L., Cixek, G. & Gough, N. (1996). Should novels count as dissertations in education?. Research in the Teaching of English, 30 (4), 403-427.

Elbaz, F. (1991). Research on teachers’ knowledge: The evolution of a discourse. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 23 (1), 1-19.

Elbaz, F. (1997). Narrative research: Political issues and implications. Teaching and Teacher Education, 13 (1), 75-83.

Fenstermacher, G. (1994a). On the virtues of van Manen's argument: A response to “Pedagogy, virtue, and narrative identity in teaching”. Curriculum Inquiry, 24 (2), 215-220.

Fenstermacher, G. (1994b). The knower and the known: The nature of knowledge in research on teaching. In L. Darling-Hammond (Ed.), Review of Research in Education, 20 (pp. 3-56). Washington: AERA.

Fenstermacher, G. & Richarson, V. (1994). Promoting confusion in educational psychology: How is it done? Educational Psychology, 29 (1), 49-55.

Gadamer, H. G. (1992). Verdad y método (Tomo II). Salamanca: Sígueme.

Geertz, C. (1989). El antropólogo como autor. Barcelona: Paidós.

Geertz, C. (1994). Conocimiento local. Ensayos sobre la interpretación de las culturas, Barcelona: Paidós.

Glaser, B. y Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

Goodson, I. (1996). Representing teachers. Essays in teachers’ lives, stories and histories. New York: Teachers College Press.

Goodson, I. & Sikes, P. (2001). Life history research in educational settings: Learning from lives. London/New York: Open Universtiy Press.

Hargreaves, A. (1986). Profesorado, cultura y postmodernidad (Cambian los tiempos, cambia el profesorado). Madrid: Morata.

Huberman, M. (1998). Trabajando con narrativas biográficas. In H. McEwan & K. Egan (Comps.), La narrativa en la enseñanza, el aprendizaje y la investigación (pp. 183-235). Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Huberman, M., Thompson, C. & Weiland, S. (2000). Perspectivas de la carrera del profesor. In B. J. Biddle, T. L. Good & I. F. Goodson (Eds.), La enseñanza y los profesores: Vol. I. La profesión de enseñar (pp. 19-38). Barcelona: Paidós.

Husserl, E. (1991). La crisis de las ciencias europeas y la fenomenología transcendental. Barcelona: Crítica.

Kushner, S. & Norris, N. (1980). Interpretation, negotiation, and validity in naturalistic research. Interchange, 11 (4), 26-36.

Lewis, O. (1966). Los hijos de Sánchez. Mexico: Joaquín Mórtiz.

Malinowski, B. (1973). Argonautas del Pacífico occidental. Barcelona: Península.

McEwan, H. (1997). The functions of narrative and research on teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 13 (1), 85-92.

McEwan, H. (1998). Las narrativas en el estudio de la docencia. In H. McEwan & K. Egan (Comps.), La narrativa en la enseñanza, el aprendizaje y la investigación (pp. 236-259). Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

McLaughlin, D. & Tierney, W. G. (Eds.). (1993). Naming silenced lives: Personal narratives and the process of educational change. New York: Routledge.

Miles, M. & Huberman, M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A source book of new methods. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Polkinghorne, D. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

Polkinghorne, D. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8 (1), 5-23.

Ricoeur, P. (1977). Expliquer et comprendre. Revue Philosophique de Louvain, 75 (1), 126-147.

Ricoeur, P. (1995). Tiempo y narración: Vol. I; Configuración del tiempo; Vol. II, Configuración del tiempo en el relato de ficción; Vol. III, El tiempo narrado. Mexico: Siglo XXI.

Tappan, M. (1997). Interpretative psychology: Stories, circles, and understanding lived experience. Journal of Social Issues, 53 (4), 645-656.

Taylor, C. (1985). Self-interpreting animals. In Human agency and language: Vol 1. Philosophical papers (pp. 45-76). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an active sensitive pedagogy. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

Van Manen, M. (1994). Pedagogy, virtue, and narrative identity in teaching. Curriculum Inquiry, 24 (2), 135-170.

Von Wright, G. (1979). Explicación y comprensión. Madrid: Alianza.

Weiler, K. & Middleton, S. (Eds.). (1999). Telling women’s lives: Narrative inquiries in the history of women’s education. Buckingham/Philadelphie: Open University Press.

Zeller, N. (1998). La racionalidad narrativa en la investigación educativa. In H. McEwan & K. Egan (Comps.), La narrativa en la enseñanza, el aprendizaje y la investigación (pp. 295-314). Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Translator: Lessie Evona York Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

1Earlier in the twentieth century, English, like Spanish, used the masculine possessive pronoun in generalized statements to indicate both genders of humankind. Since the advent of the feminist movement, however, such usage in English has been considered sexist, is generally avoided, and has been replaced by expressions such as “his and her”, “s/he” etc. (Fennel, Francis, 2002). While these non-sexist devices can be comfortably employed now and then in a work, their constant and continual use becomes awkward. In this work, in order to avoid the annoying repetition of such constructions, we shall at times use the feminine pronoun (she, her, etc.) and at times, the masculine (he, him, his, etc.).

2Translator’s note: Some texts quoted in this work were available to the original authors of this work only in their Spanish translations. Because the original texts were unavailable to the translator, we have been obliged to use the technique of back-translation, for which we most humbly apologize.

Please cite the source as:

Bolivar, A. (2002). “De nobis ipsis silemus?”: Epistemology of Biographical-Narrative Research in Education . Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 4 (1). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol4no1/contents-bolivar.html