Design and Evaluation of Basic Generic Skills for University and Business1

Cómo citar: Crespí, P. y García-Ramos, J. M. (2023). Design and Evaluation of Basic Generic Skills for University and Business. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 25, e22, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2023.25.e22.4600

Abstract

The formative development of generic skills is necessary in any field, and accordingly, these skills are becoming increasingly supported in education and sought after by businesses. The objective of this article is to present and validate the scores of an instrument used to measure basic generic skills. This was achieved by first defining the construct of generic skills and then identifying the underlying dimensions, subdimensions, and indicators, and preparing the items. The final version of the questionnaire was administered to a sample of 547 freshman college students in the Community of Madrid. The analyses indicate that the scores of the questionnaire are reliable and valid and support the theoretical model. The findings show an adequate questionnaire that can be used to measure the development of basic generic skills and assess education provided in this respect.

Keywords: competences, skills development, higher education

I. Introduction

In our everchanging and complex society generic or transversal competences play an increasingly important role in the personal, social, educational or professional advancement and fulfilment of individuals. It is increasingly critical to develop, and to evaluate, generic competences as part of the basic education of young people and an essential aspect of the mission of universities. These competences encompass a wide range of valuable personal skills and abilities such as proactivity, self-awareness, innovation, creativity, entrepreneurship, empathy, effective communication, active listening, resilience, teamwork, leadership, decision-making, conflict resolution, etc. (Crespí & García-Ramos, 2021; European Commission, 2017; Domínguez, 2018; García, 2017; Ruiz et al., 2017; Unesco, 2015).

The European Union has repeatedly emphasised the need for citizens to acquire and develop key competences, both specific and generic, throughout their lives (lifelong learning) leading to personal growth and fulfilment. The PISA Program (1997) and the Lisbon European Council (2000) expressly refer to the need for education to promote the acquisition of key competences, understood as those required by everyone for their own personal, social and professional fulfilment and advancement (European Commission, 2018; Lundgren, 2013; OECD, 2018; Order ECD/65/2015; Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019; Recomendation 2006/962/EC).

Through the Bologna Declaration (1999) and the Tuning Project of 2000, the EU has laid the foundation for the creation of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) which incorporates the learning and evaluation of specific and generic competences as essential elements of all university study programs (González & Wagenaar, 2006). Tuning (2006) defines specific competences as those “proper to or specific to a field of study” while generic competences are those which “are common to any education program” (p. 3). Thus, the acquisition of both specific and generic competences is considered a prerequisite for obtaining a university degree, with particular emphasis on the latter, referred to as transversal or “21st century competences” that must be incorporated into study programs (Aguado et al., 2017; Almerich et al., 2018).

The importance of generic or transversal competences in the business world was first raised in the pioneering work of McClelland (1973) who proposed evaluating competence was more important than evaluating intelligence and regarded the possession of certain competences as the key to personal and professional excellence. And so began the Competences Movement, the increasing orientation of businesses towards managing, selecting, training and evaluating competences as essential to effective business management, especially in boosting productivity and profitability. Hence the importance of generic professional competences, so-called soft skills, common to all professions or productive environments (Alles, 2017; Cardona & García-Lombardía, 2007; García, 2018; González, 2017; Gutiérrez, 2010; Mertens, 1996; Olaz, 2018; Pozo, 2017; Spencer & Spencer, 1993).

Thus, generic competences play a critical role in the development and advancement of an individual and it is therefore essential these competences be taught and evaluated at university.

Generic competences are rarely taught in a subject of their own but are most commonly incorporated into the curriculum through other specific or technical courses within the degree program. Another method is through complementary activities, workshops, preliminary or optional courses, coaching sessions, etc. imparted by specialised teachers (Bécart, 2015; Crespí & García-Ramos, 2021; Gijón, 2016; Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019; Villa & Poblete, 2011; Villardón-Gallego, 2015).

These competences are generally evaluated using specific rubrics or scales designed to measure each competence, their level of development or acquisition, using key indicators and descriptors (Gimeno et al., 2011; Herrero et al., 2014; López, 2017; Villa & Poblete, 2007).

A number of questionnaire have been developed which measure these competences or specific indicators (Arias et al., 2011; Clemente-Ricolfe & Escribá-Pérez, 2013; Gargallo et al., 2018; Lazo et al., 2009; Martínez-Clares & González-Lorente, 2019; Ruiz, 2010). However, there is a lack of questionnaires specifically designed to evaluate basic generic competences in university and business in a comprehensive person-centred manner.

Thus, with the aim of meeting the need for an effective, reliable and valid questionnaire to evaluate generic competences, this research project has two objectives: 1) to present the design and construction of the measurement instrument; and 2) to determine the reliability and validity of the questionnaire results.

This article presents the Basic Generic Competences Questionnaire (BGCQ), which may serve as a valuable tool in the measurement of the degree of acquisition of the generic competences considered most elemental in all areas of life: academic, social, personal and professional. This tool was developed with the context of university education but is equally applicable in personal or professional contexts. Furthermore, the self-report format of the BGCQ is especially effective in evaluating students’ self-perception of their skills (Ruiz et al., 2017; Villa & Poblete, 2011).

II. Method

2.1 Participants

The target population of the study was first-year university students in the Community of Madrid. To ensure a sufficiently representative sample, the population was defined to include students at both a private and public university: the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria (UFV) and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM). Incidental convenience sampling method was used and the sample size was calculated using the Ene 3.0 statistics program with a confidence interval of 95%, a standard deviation of 3 and a precision level of 0.40. Taking the number of enrolled students as a reference, the program estimated a minium sample size of 444 first-year students, identified by faculty at the UFV (all faculties) and the UCM (the faculty of Education).

The sample used in this research is therefore considered appropriate both in terms of size and representativeness (see Table 1).

| Faculty | Degree | Enrolled students | Minimum sample | Final sample | Response percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Pre-primary and Primary Education UCM | 670 | 217 | 193 | 28.8 |

| Pre-primary and Primary Education UFV | 75 | 18 | 60 | 80.0 | |

| Law and Business | Law UFV | 137 | 50 | 60 | 43.8 |

| Gastronomy UFV | |||||

| Law + BA UFV | |||||

| Health Sciences | Medicine UFV | 217 | 77 | 89 | 41.0 |

| Psychology UFV | |||||

| Experimental Sciences | Biomedicine UFV | 95 | 25 | 47 | 49.5 |

| Advanced Polytechnical School | Computer Engineering UFV | 64 | 12 | 45 | 70.3 |

| Architecture UFV | |||||

| Communication Sciences | Journalism UFV | 126 | 45 | 53 | 42.1 |

| Audio-visual Communication UFV | |||||

| Total | 1384 | 444 | 547 | 39.5 |

2.2 Design of the instrument

The first step was to define the construct ”generic competence”. For this, a number of leading authors were consulted in the fields of both education and business. In education, generic competences generally refer to those which are common to various subjects or degrees; in business, they are those which are considered common to various different professions (Belzunce et al., 2011; González, 2017; González & Wagenaar, 2006; Gutiérrez, 2010; Poblete & García, 2007).

We proposed a definition of competence and generic competence. Competence is defined as “a dynamic set of knowledge (know), abilities (know how to do), attitudes and values (Know how to be) that, internalised and manifested in our actions, attitudes and behaviours, put us on the path towards maturity, excellence, personal fulfilment and happiness” (Crespí, 2019, p. 98). Generic competences are defined as “those which can be associated with excellence in any circumstances of life, be they personal, social, academic or professional” (Crespí, 2019, p. 100).

On this basis, we compiled a list of basic generic competences which may be considered necessary regardless of one’s chosen field of study or profession. We also drew on studies from business and universities which differentiate between intrapersonal and interpersonal competences (Aguado et al., 2017; Beneitone et al., 2007; Benito & Cruz, 2006; Felce et al., 2016; González & Wagenaar, 2006; Palmer et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2000; Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019).

The Basic Generic Competences Questionnaire (BGCQ) (Cuestionario de Competencias Genéricas Básicas (CCGB)) also considers these two dimensions. The intrapersonal dimension refers to competences which facilitate knowledge, acceptance and personal responsibility (introspection: subdimension 1), as well as those which enable reflection on one’s own life, the ability to set objectives and the proactivity to achieve them (personal development: subdimension 2). The interpersonal dimension refers to competences which facilitate social interaction and cooperation with others (teamwork: subdimension 3), and those which facilitate interaction and communication (effective communication: subdimension 4). The BGCQ is structured into two dimensions and four subdimensions and 36 sub-indicators (see Table 2). The initial design of the instrument consisted of 45 items: 9 referring to identification and the remaining 36 referring to the 36 different sub-indicators. The questionnaire uses a Likert-type response scale from one to six, thus avoiding a middling trend in the answers.

| Dimension (D) | Subdimension (S) | Indicators (I) | Sub-indicators (SI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Introspection. Deep look | Self-awareness | Strengths |

| Areas for improvement | |||

| Distinctive personal characteristics | |||

| Self-acceptance | Strengths and areas for improvement | ||

| Unique and irreplaceable | |||

| Being in constant development | |||

| Self-management | Self-reliance | ||

| Attribution of causality | |||

| Responsibility | |||

| Personal development | Search for meaning in life | Meaning of life | |

| Vocation | |||

| Life project | |||

| Orientation to excellence | Objectives of development | ||

| Objectives involving a challenge | |||

| Mentor or tutor | |||

| Proactivity. Self-discipline | Action | ||

| Overcoming obstacles | |||

| Initiative | |||

| Interpersonal | Teamwork | Cooperative work | Involvement and engagement |

| Attitude of service and support | |||

| Integration into the team | |||

| Work environment management | Politeness and respect | ||

| Attitude | |||

| Motivation | |||

| Orientation towards results | Planning and organisation | ||

| Assuming tasks | |||

| Compliance with obligations | |||

| Effective communication | Verbal communication | Key ideas | |

| Structure | |||

| Clarity | |||

| Paraverbal and non-verbal communication | Visual contact | ||

| Body and hands | |||

| Rhythm and tone | |||

| Communication for encounter | Empathy | ||

| Assertiveness | |||

| Active listening |

2.3 Validation by experts

Once an initial version of the BGCQ was completed the validity of the contents was analysed by a panel of 18 experts in research, education and academic and business competences. For this, a Likert-type evaluation scale was created (1 to 6) with three sections.

The first section was designed to validate the presentation and instructions of the questionnaire, and the identification data based on four criteria: clarity, length, quality and aptness. The resulting scores were between 5.17 and 5.56. The homogeneity of the responses was evaluated using the Pearson variation coefficient, with results between 0.11 and 0.20, indicating the homogeneity of the evaluations.

The second section was to validate the aptness of the items for the dimensions and participants as well as the clarity of the questions. The tool scored 5.62 for coherence, 5.33 for clarity and 5.73 for aptness for participants. The scores for the dimensions and subdimensions were above 5.18 in all cases with the Pearson variation coefficient indicating the homogeneity of the responses (see Table 3).

| Coherence | Clarity | Aptness for participants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation criteria | Mean | Stan.. Dev | Variation Coef. | Mean | Stan.. Dev | Variation Coef. | Mean | Stan.. Dev | Variation Coef. | |

| Global Questionnaire | 36 | 5.62 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 5.33 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 5.73 | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| D. Intrapersonal | 18 | 5.52 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 5.21 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 5.68 | 0.21 | 0.04 |

| D. Interpersonal | 18 | 5.73 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 5.45 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 5.77 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| S. Introspection | 9 | 5.48 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 5.24 | 0.42 | 0.08 | 5.67 | 0.27 | 0.05 |

| S. Personal development | 9 | 5.55 | 0.38 | 0.07 | 5.18 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 5.69 | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| S. Teamwork | 9 | 5.74 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 5.29 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 5.77 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| S. Communication | 9 | 5.72 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 5.61 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 5.78 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

The third section provided a general evaluation of the questionnaire in terms of the number of items, their logical order and the validity of the content. The mean scores in this section were above 5 in all cases and the variation coefficient was near zero (see Table 4) indicating a positive and homogeneous evaluation of the scale.

| Evaluation criteria | Mean | Stan.. Dev | Variation Coef. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logical order of presentation | 5.44 | 0.70 | 0.13 |

| Number of items | 5.06 | 1.16 | 0.23 |

| Validity of content | 5.11 | 0.76 | 0.15 |

Based on this expert evaluation the questionnaire was considered to be sufficiently valid. However, in light of the qualitative and quantitative evaluations by the panel of experts, a number of items were reformulated, the clarity of the entire scale was reviewed and recommended changes were made to the instructions and identification data. Thus, the final version of the BGCQ was obtained (Annex 1).

2.4 Data collection and analysis

The Universidad Francisco de Vitoria and the Universidad Complutense de Madrid were contacted to arrange the survey of students. The resulting data was analysed using the IBM SPSS statistics program version 21. To estimate the validity of the tool the mean scores, standard deviation and Pearson variation coefficient were calculated. To confirm the reliability of the instrument the Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated and the Homogeneity Index (HI) and Validity Index (VI) were also analysed. To verify the criterion validity the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated. Finally, a number of Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analyses (AFC) were carried out, the latter using the AMOS subprogram of the SPSS.

III. Results

A reliability test was conducted to evaluate the internal consistency of the scale; that is, to determine if all items measure the construct with sufficient precision. For this, the Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated, taking the references of George and Mallery (2003), whereby scores equal to or above 0.9 are considered excellent and scores between 0.8 to 0.89 are good. The analysis confirmed the excellent internal consistency of the complete questionnaire and its two dimensions, and the good consistency of its subdimensions (see Table 5). The questionnaire can therefore be considered highly reliable.

| Degree of reliability | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Global Questionnaire | 36 | 0.94 |

| D. Intrapersonal | 18 | 0.90 |

| D. Interpersonal | 18 | 0.90 |

| S. Introspection | 9 | 0.83 |

| S. Personal development | 9 | 0.83 |

| S. Teamwork | 9 | 0.83 |

| S. Effective communication | 9 | 0.86 |

The results of the analyses of homogeneity and validity were satisfactory for all items, with scores above 0.20.

The convergent criterion validity was analysed to verify that the global instrument, its dimensions and subdimensions in fact measure the variables for which it was designed: generic, interpersonal and intrapersonal competences, introspection, effective communication, personal development and teamwork. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated, using the benchmarks recommended by García (2012), where scores between 0.60 and 0.69 are considered good and scores from 0.50 to 0.59 are considered acceptable-minimum.

The instrument showed a good degree of validity for the global questionnaire and the intra and interpersonal dimensions; the results were acceptable in the case of introspection and effective communication and minimally acceptable for personal development and teamwork (see Table 6).

| Degree of validity | Items | Pearson’s Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Global Questionnaire | 36 | 0.69 |

| D. Intrapersonal | 18 | 0.64 |

| D. Interpersonal | 18 | 0.65 |

| S. Introspection | 9 | 0.60 |

| S. Personal development | 9 | 0.59 |

| S. Teamwork | 9 | 0.55 |

| S. Effective communication | 9 | 0.63 |

3.1 Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis permits a comparison between the theoretical structure of the BGCQ and its empirical structure; that is, to demonstrate the validity of the construct of generic competences. First, a Bartlett’s sphericity test was carried out, showing a significance of 0.00 and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index was calculated as 0.94. These results indicate that the correlation matrix has sufficient variance to merit continuing with the analysis.

Three complete exploratory factor analyses were carried out. The first used principal component analysis (PCA), with 7 significant factors. The oblique rotation matrix (PCA+Oblimin) was that which best fit the criteria of the Thurstone simple structure. Vernon’s criterion was used to analyse the results, where values equal to or above 0.50 show a high weighting in the definition of the factor and significant with regard to the variables. Thus, it can be affirmed that the intrapersonal dimension is clearly shown in factors 1, 4 and 7 and the interpersonal dimension in factors 2, 3, 5 and 6.

The second EFA used maximum likelihood factoring (MLF) technique, showing 7 significant factors. The oblique rotation matrix (MLF+Oblimin) also proved to be that which best fit the Thurstone simple structure criteria. Here again, the results showed that the important variables (with saturation equal to or above 0.50) in the intrapersonal dimension were in factors 1, 4 and 5; and factors 2, 3, 6 and 7 for the interpersonal dimension.

Finally, a third EFA was carried out to contrast the results of the first two, using a principal component analysis (PCA). In this case, the solutions are forced to 4 significant factors in order to compare the theoretical structure of the four subdimensions. The oblique rotation matrix (PCA+Oblimin) also offered the best fit. The results show that introspection is clearly identified with factor 1, personal development with factor 4, teamwork with factor 2, and effective communication with factor 3 (see Table 7). Furthermore, the correlation matrix shows significant correlations between all factors, indicating significant correspondence between the empirical and theoretical structure of the BGCQ.

| Dimension | Subdimension | Item | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Introspection | 5 | 0.76 | |||

| 6 | 0.55 | |||||

| 7 | 0.66 | |||||

| 8 | 0.75 | |||||

| 9 | 0.67 | |||||

| 10 | 0.44 | |||||

| 11 | 0.54 | |||||

| 12 | 0.43 | |||||

| 13 | ||||||

| Personal development | 14 | 0.67 | ||||

| 15 | 0.63 | |||||

| 16 | 0.73 | |||||

| 17 | 0.53 | |||||

| 18 | 0.53 | |||||

| 19 | 0.38 | |||||

| 20 | 0.44 | |||||

| 21 | 0.53 | |||||

| 22 | 0.48 | |||||

| Interpersonal | Teamwork | 23 | 0.64 | |||

| 24 | 0.73 | |||||

| 25 | 0.7 | |||||

| 26 | 0.63 | |||||

| 27 | 0.75 | |||||

| 28 | 0.53 | |||||

| 29 | ||||||

| 30 | 0.67 | |||||

| 31 | 0.56 | |||||

| Effective communication | 32 | -0.4 | ||||

| 33 | -0.4 | |||||

| 34 | -0.6 | |||||

| 35 | -0.8 | |||||

| 36 | -0.7 | |||||

| 37 | -0.7 | |||||

| 38 | ||||||

| 39 | ||||||

| 40 | 0.39 | 0.36 | ||||

| Note: Values equal to or above 0.50 indicate a high weighting factor. | ||||||

3.2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

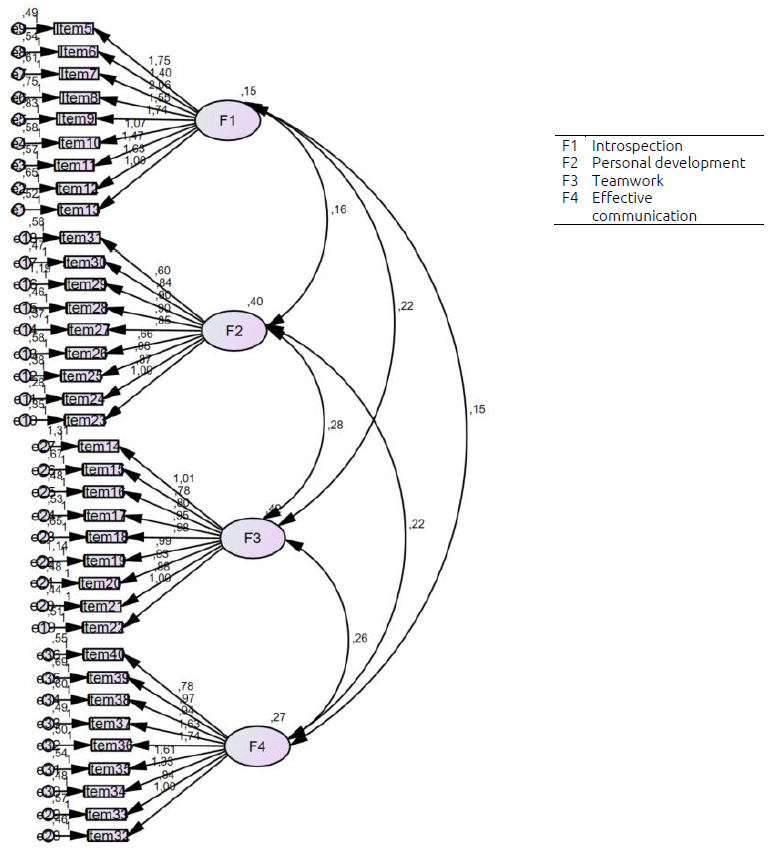

A confirmatory factor analysis can best reveal the dimensional structure of the questionnaire and thus the measurement of the construct “generic competences”. A CFA was carried out using structural equations modelling (see Figure 1).

The most habitual goodness of fit statistics are provided below along with the acceptable criteria for aa positive evaluation allowing the results to be compared (see Table 8). In general, the degree of fit is low for the majority of indicators. The chi-squared values are significant, probably due to the large sample size. Almost all other values are lower than desired (PNFI, NFI, IFI, TLI and CFI). However, the RMSEA is below 0.08, suggesting an adequate fit and the values for this index are very close to a good fit between the data and the theoretical model (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

| Statistics | Abrev. | Criterion | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ajuste absoluto | |||

| Chi-squared | x2 | 2052.701 | |

| Degrees of freedom | gl | Sig. > .05 | 588 |

| Level of probability | p | .000 | |

| Comparative fit | |||

| Comparative goodness of fit index | CFI | > 0.9 | 0.816 |

| Tucker-Lewis index | TLI | > 0.9 | 0.803 |

| Incremental fit index | IFI | > 0.9 | 0.817 |

| Normalised fit index | NFI | Próximo a 1 | 0.761 |

| Parsimonious fit | |||

| Corrected parsimony | PNFI | Próximo a 1 | 0.701 |

| Others | |||

| Root mean square error of approximation | RMSEA | < 0.08 | 0.068 |

Additionally, the regression weight with the parameters is also shown; SE (standard error), estimation, CR (critical ratio) and a probability score for each parameter. It can be seen that the regression weight between variables are all significant, without excessive saturation but satisfactory in the majority of cases (see Table 9).

| Estimation | SE | CR | p | Etiqueta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ítem13 | <--- | Introspection | 1 | ||||

| Ítem12 | <--- | Introspection | 1.634 | 0.17 | 9.62 | *** | par_1 |

| Ítem11 | <--- | Introspection | 1.465 | 0.154 | 9.49 | *** | par_2 |

| Ítem10 | <--- | Introspection | 1.075 | 0.129 | 8.333 | *** | par_3 |

| Ítem9 | <--- | Introspection | 1.74 | 0.185 | 9.419 | *** | par_4 |

| Ítem8 | <--- | Introspection | 1.555 | 0.169 | 9.221 | *** | par_5 |

| Ítem7 | <--- | Introspection | 2.063 | 0.2 | 10.304 | *** | par_6 |

| Ítem6 | <--- | Introspection | 1.397 | 0.149 | 9.405 | *** | par_7 |

| Ítem5 | <--- | Introspection | 1.746 | 0.172 | 10.173 | *** | par_8 |

| Ítem24 | <--- | Personal development | 0.874 | 0.055 | 15.903 | *** | par_9 |

| Ítem25 | <--- | Personal development | 0.978 | 0.063 | 15.561 | *** | par_10 |

| Ítem26 | <--- | Personal development | 0.66 | 0.063 | 10.533 | *** | par_11 |

| Ítem27 | <--- | Personal development | 0.854 | 0.058 | 14.607 | *** | par_12 |

| Ítem28 | <--- | Personal development | 0.903 | 0.064 | 14.11 | *** | par_13 |

| Ítem29 | <--- | Personal development | 0.9 | 0.089 | 10.15 | *** | par_14 |

| Ítem30 | <--- | Personal development | 0.843 | 0.062 | 13.503 | *** | par_15 |

| Ítem31 | <--- | Personal development | 0.6 | 0.062 | 9.737 | *** | par_16 |

| Ítem22 | <--- | Teamwork | 1 | ||||

| Ítem21 | <--- | Teamwork | 0.875 | 0.064 | 13.593 | *** | par_17 |

| Ítem20 | <--- | Teamwork | 0.931 | 0.068 | 13.745 | *** | par_18 |

| Ítem19 | <--- | Teamwork | 0.987 | 0.09 | 10.958 | *** | par_19 |

| Ítem18 | <--- | Trabajo en equipo | 0.979 | 0.075 | 12.995 | *** | par_20 |

| Ítem17 | <--- | Teamwork | 0.949 | 0.07 | 13.522 | *** | par_21 |

| Ítem16 | <--- | Teamwork | 0.798 | 0.063 | 12.601 | *** | par_22 |

| Ítem15 | <--- | Teamwork | 0.777 | 0.069 | 11.181 | *** | par_23 |

| Ítem14 | <--- | Teamwork | 1.012 | 0.095 | 10.634 | *** | par_24 |

| Ítem32 | <--- | Effective communication | 1 | ||||

| Ítem33 | <--- | Effective communication | 0.844 | 0.082 | 10.25 | *** | par_25 |

| Ítem34 | <--- | Effective communication | 1.332 | 0.1 | 13.354 | *** | par_26 |

| Ítem35 | <--- | Effective communication | 1.606 | 0.115 | 13.961 | *** | par_27 |

| Ítem36 | <--- | Effective communication | 1.74 | 0.121 | 14.405 | *** | par_28 |

| Ítem37 | <--- | Effective communication | 1.632 | 0.115 | 14.224 | *** | par_29 |

| Ítem38 | <--- | Effective communication | 0.938 | 0.087 | 10.734 | *** | par_30 |

| Ítem39 | <--- | Effective communication | 0.973 | 0.092 | 10.547 | *** | par_31 |

| Ítem40 | <--- | Effective communication | 0.778 | 0.079 | 9.836 | *** | par_32 |

| Ítem23 | <--- | Personal development | 1 | ||||

| Note: SE. = Standard error; CR =Critical ratio; p = *** = .000 | |||||||

Finally, the regression wights between subdimensions and their associated probability values show that all relations are statistically significant although not high (see Table 10).

| Estimation | SE | CR | p | Label | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introspection | <--> | Personal development | 0.157 | 0.02 | 7.807 | *** | par_33 |

| Teamwork | <---> | Effective communication | 0.264 | 0.028 | 9.423 | *** | par_34 |

| Introspection | <---> | Teamwork | 0.219 | 0.026 | 8.361 | *** | par_35 |

| Personal development | <---> | Teamwork | 0.284 | 0.03 | 9.6 | *** | par_36 |

| Introspection | <---> | Effective communication | 0.146 | 0.019 | 7.75 | *** | par_37 |

| Personal development | <---> | Effective communication | 0.216 | 0.024 | 9.041 | *** | par_38 |

IV. Discussion and conclusions

Generic or transversal competences play a critical role in personal, academic and professional excellence (Juárez & González, 2018; Lundgren, 2013; Mederos-Piñeiro, 2016; Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019; Unesco, 2015).

This project for the design and validation of the BGCQ aims to respond to the need for the effective evaluation of these competences in higher education. The results show that the BGCQ is a reliable and valid instrument to measure the degree of acquisition of basic generic competences, defined using an integral, person-centred approach incorporating different dimensions (personal, social, academic and professional). It is offered a universally acceptable definition of competence that can be used in any context and that can be recognised both in the field of business and education; something which has been called for by many authors in order to create better synergies and point of encounter between education and employment (Gijbels, 2011; Martínez et al., 2019; Ruiz et al., 2017).

The instrument incorporates the basic generic competences to be taught and evaluated in higher education, especially in the first year of degree programs. Authors have signalled the importance of focussing on a limited number of competences (Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019), and the BGCQ proposes four broad categories of basic competence: introspection (self-awareness, self-acceptance and self-management), personal development (search for meaning in life, orientation towards excellence and proactivity), teamwork (cooperative work, work environment management and orientation towards results) and effective communication (verbal, paraverbal and non-verbal communication and communication for encounter).

These competences are very similar or complementary to those considered critical for any area of study or profession and for life in general (Beneitone et al., 2007; Benito & Cruz, 2006; González & Wagenaar, 2006; Palmer et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2000; Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019). For each of the four competences (subdimensions) 3 specific competences are identified (indicators) and 3 key elements (sub-indicators), corresponding to each of the items of the instrument. This dimensional structure and their associated items were analysed for validity by a panel of 18 experts. The resulting scores for the dimensions, subdimensions and the global questionnaire (above 5 out of 6) and the consistency of the scores indicate the questionnaire is a sufficiently valid tool.

The tool shows excellent internal consistency, both in global scores and in each dimension. An analysis of the homogeneity and validity of the items provided satisfactory values, showing an adequate contribution to their respective dimensions and subdimensions. The results of the convergent criterion analysis were also satisfactory, both for the global scale and the dimensions. The EFA confirms in part the dimensional structure of the instrument with an adequate general correspondence between the theoretical and empirical structures of the BGCQ. Finally, the CFA indicated a more than acceptable fit for some indicators and less so with others.

Thus, it can be affirmed that the BGCQ is a valid tool to evaluate the acquisition of basic generic competences and the degree of progress in their development. This is important given that the competence level is determined by both professors and students based on self-reported perceptions (Gimeno et al., 2011; Hierro et al., 2016). Given that both teachers and students play an important role in the evaluation of these competences, a wide variety of valid and reliable measurement tools is required (García et al., 2010; Hierro et al., 2016; Ibarra et al., 2010; Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019).

There are a number of questionnaires which use self-reporting to evaluate student competences and there are a range of tools available to measure transversal, professional, specific or a mixed variety of competences, some evaluating competences and others measuring competence indicators (Arias et al., 2011; Clemente-Ricolfe & Escribá-Pérez, 2013; Gargallo et al., 2018; Lazo et al., 2009; Martínez-Clares & González-Lorente, 2019; Ruiz, 2010). Given that no specific instruments are aimed at the measurement of basic generic competences at universities and in business using an integral, person-centred approach, the BGCQ can be considered a significant contribution to the field.

This questionnaire responds to the need for quality evaluation scales that incorporate levels of acquisition, indicators and descriptors for each competence (Gimeno et al., 2011; Herrero et al., 2014; Villa & Poblete, 2007). Thus, the BGCQ constitutes an effective self-report evaluation tool for students and aims to serve as a useful complement in the development of learning/teaching methodologies and evaluation techniques such as mind maps, conceptual maps, portfolios, interviews, collaborative learning (CL) case studies, problem-based and project-based learning (PBL) simulations or learning by doing (Cáceres-Lorenzo & Salas-Pascual, 2012; Gallardo-López et al., 2017; García & Gairín, 2011; Jauregui, 2018; Pozo, 2017; Pugh & Lozano-Rodríguez, 2019; Villa & Poblete, 2011).

The BGCQ can also serve to determine the effectiveness of education programs for generic competences by evaluating the competence levels of students before and after courses or programs, identifying competences which are more or less acquired, for the reorientation, readjustment or redesign of programs. It can also be useful in a complementary tool in the recruitment or evaluation of personnel. Human resources departments, well aware of the difficulty and cost of developing essential generic competences compared to more technical skills, can conduct more rigorous selection processes using these types of tools (Alles, 2017; García, 2018).

It can therefore be concluded that the BGCQ is a reliable and valid instrument to measure the degree of acquisition of basic general competences based on the results of exhaustive research into these competences and a rigorous validation process. The tool has a comprehensive, integrated design appropriate for addressing generic competences in any field. Thus, although the origins of the BGCQ are in higher learning and academia it is an instrument that can be applied in other areas, both personal and professional. Nevertheless, it is important for researchers to continue designing and proposing new evaluation instruments and programs to measure these essential competences.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Sources of funding

This research received no external funding.

References

Aguado, D., González, A., Antúnez, M. y de Dios, T. (2017). Evaluación de competencias transversales en universitarios. Propiedades psicométricas iniciales del cuestionario de competencias transversales. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 15(2), 129-152. https://doi.org/10.15366/reice2017.15.2.007

Alles, M. A. (2017). Elija al mejor. La entrevista en selección de personas. La entrevista por competencias. Ediciones Granica.

Almerich, G., Díaz-García, I., Cebrián-Cifuentes, S. y Suárez-Rodríguez, J. (2018). Estructura dimensional de las competencias del siglo XXI en alumnado universitario de educación. RELIEVE, 24(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.24.1.12548

Arias, E., Pacheco, M., Cabré, V., Castillo, J. A., Echevarría, R., Gómez, A. M., Herrero, O., Pérez, C. y Rusiñol, J. (2011). Plantilla d’Observació i Avaluació de Competències (POAC): millora de la qualitat docent en l’avaluació psicològica [Plantilla de observación y evaluación de competencias (POAC): mejora de la calidad docente en la evaluación psicológica]. Aloma.Revista de Psicología, Ciències de l'Educació i de l'Esport, (29), 189-206. http://www.revistaaloma.net/index.php/aloma/article/view/121

Belzunce, M. J., Danvila, I. y Martínez-López, F. J. (2011). Guía de competencias emocionales para directivos. ESIC Editorial.

Beneitone, P., Esquetini, C., González, J., Marty, M., Slufi, G. y Wagenaar, R. (2007). Reflexiones y perspectivas de la educación superior en América Latina. Informe Final. Proyecto Tuning América Latina 2004-2007. Universidad de Deusto.

Benito, A. y Cruz, A. (2006). Nuevas claves para la docencia universitaria en el espacio europeo de educación superior. Narcea.

Bécart, A. (2015). Impacto del coaching en el desarrollo de competencias para la vida. Un estudio de caso en el Caribe colombiano. Universidad Pablo de Olavide.

Cardona, P. y García-Lombardía, P. (2007). Cómo desarrollar las competencias de liderazgo (3a. ed.). Universidad de Navarra.

Clemente-Ricolfe, J. S. y Escribá-Pérez, C. (2013). Análisis de la percepción de las competencias genéricas adquiridas en la Universidad. Revista de Educación, (362), 535-531. https://dx.doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2013-362-241

Crespí, P. (2019). La necesidad de una formación en competencias personales transversales en la universidad. Diseño y evaluación de un programa de formación. Fundación Universitaria Española.

Crespí, P. y García-Ramos, J. M. (2021). Competencias genéricas en la universidad. Evaluación de un programa formativo. Educación XX1, 24(1), 297-327. http://doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.26846

Cáceres-Lorenzo, M. T. y Salas-Pascual, M. (2012). Valoración del profesorado sobre las competencias genéricas: Su efecto en la docencia. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 3(2), 195-210.

Comisión Europea. (2017). Comunicación de la Comisión al Parlamento Europeo, al Consejo, al Comité Económico y Social Europeo y al Comité de las Regiones sobre una agenda renovada de la UE para la educación superior. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017DC0247&from=FI

Comisión Europea. (2018). Anexo de la Propuesta de Recomendación del Consejo relativa a las competencias clave para el aprendizaje permanente. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H0604%2801%29

Domínguez, X. M. (2018). Ética del docente. Fundación Emmanuel Mounier.

Felce, A., Perks, S. y Roberts, D. (2016). Work-based skills development: a context-engaged approach. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 6(3), 261-276. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-12-2015-0058

Gallardo-López, B., Pérez-Pérez, C., Verde-Peleato, I. y García-Félix, E. (2017). Estilos de aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios y enseñanza centrada en el aprendizaje. RELIEVE, 23(2), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.23.2.9078

García, N. C. (2018). Evaluación del desempeño del talento humano basado en competencias: evaluación por competencias, desarrollo del capital humano. Editorial Académica Española.

García, M. J., Arranz, G., Blanco, J., Edwards, M., Hernández, W., Mazadiego, L. y Piqué, R. (2010). Ecompetentis: una herramienta para la evaluación de competencias genéricas. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 8(1), 111-120. https://doi.org/10.4995/redu.2010.6220

García, J. M. (2012). Fundamentos pedagógicos de la evaluación. Guía práctica para educadores. Editorial Síntesis.

García, J. M. (2017). Misión de la universidad en los tiempos de la postverdad. Ávila.

García, M. J. y Gairín, J. (2011). Los mapas de competencias: una herramienta para mejorar la calidad de la formación universitaria. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 9(1), 84-102. https://revistas.uam.es/reice/article/view/4719

Gargallo, B., Suárez-Rodríguez, J. M., Almerich, G., Verde, I. y Cebriá, M. A. (2018). Validación del cuestionario SEQ en población universitaria española. Capacidades del alumno y entorno de enseñanza/aprendizaje. Anales de Psicología, 34(3), 519-530. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.34.3.299041

George, D. y Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. Allyn and Bacon.

Gijbels, D. (2011). Assessment of vocational competence in higher education: reflections and prospects. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(4), 381-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.581859

Gijón, J. (2016). Competencias en la educación superior, en J. Gijón (Coord.), Formación por competencias y competencias para la formación. Perspectivas desde la investigación. Síntesis.

Gimeno, M., Vendrell, R., Isanta, C. y Arias, E. (2011). Com formar i avaluar per competències per part dels tutors dels seminaris de Grau [Cómo formar y evaluar por competencias por parte de los tutores de los seminarios de Grado]. Aloma. Revista de Psicología, Ciències de l'Educació i de l'Esport, (29), 97-111. http://www.revistaaloma.net/index.php/aloma/article/view/125

González, A. L. (2017). Métodos de compensación basados en competencias (3a. ed.). Editorial Universidad del Norte.

González, J. y Wagenaar, R. (2006). Tuning educational structures in Europe II. La contribución de las universidades al Proceso de Bolonia. Universidad de Deusto.

Gutiérrez, E. (2010). Competencias gerenciales: habilidades, conocimientos, aptitudes. Ecoe Ediciones.

Herrero, R., Ferrer, M. A. y Calderón, A. A. (2014). Evaluación de las competencias genéricas mediante rúbricas. Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, (7), 13-22. https://repositorio.upct.es/bitstream/handle/10317/4115/ecg.pdf

Hierro, L. A., Patiño, D., Atienza, P. y Gómez-Álvarez, R. (2016). Evaluación cuantitativa de competencias genéricas y específicas en la docencia de Economía del Sector Público. e-pública, (18), 31-48. http://e-publica.unizar.es/es/articulo/1813

Hu, L. T. y Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Ibarra, M. S., Cabeza, D., León, A. R., Rodríguez, G., Gómez, M. A., Gallego, B., Quesada, V. y Cubero, J. (2010). EvalCOMIX en Moodle: un medio para favorecer la participación de los estudiantes en la e-evaluación. Revista de Educación a Distancia, (24), 1-11. https://revistas.um.es/red/article/view/125241

Jauregui, T. (2018). Estrategia didáctica para fortalecer las competencias genéricas en educación superior. Editorial Académica Española.

Juárez, A. y González, M. O. (2018). La construcción de las competencias genéricas en el nivel superior. Revista Atlante: cuadernos de Educación y Desarrollo. https://www.eumed.net/rev/atlante/2018/01/competencias-genericas.html

Lazo, C. M., Sierra, J. y Cabezuelo, F. (2009). La evaluación de las competencias alcanzadas en el Proyecto Final de las titulaciones de comunicación.@tic.Revista d'Innovació Educativa, (2), 48-55. https://ojs.uv.es/index.php/attic/article/view/82

Lundgren, U. P. (2013). PISA como instrumento político. La historia detrás de la creación del programa PISA. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 17(2), 15-29. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/profesorado/article/view/42101

López, M. A. (2017). Aprendizaje, competencias y TIC (2a. ed.). Pearson Educación.

Martínez, P., González, C. y Rebollo, N. (2019). Competencias para la empleabilidad: un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales en la Facultad de Educación. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 31(1), 57-73. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.37.1.343891

Martínez-Clares, P. y González-Lorente, C. (2019). Competencias personales y participativas vinculantes a la inserción laboral de los universitarios: validación de una escala. RELIEVE, 25(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.25.1.13164

McClelland, D. C. (1973). Testing for Competence rather than for "intelligence". American Psychologist, 28(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034092

Mederos-Piñeiro, M. (2016). La formación de competencias para la vida. Ra Ximhai, 12(5), 129-144.

Mertens, L. (1996). Competencia laboral: sistemas, surgimiento y modelos. Montevideo: Cinterfor.

OECD. (2018). The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf

Olaz, A. J. (2018). Guía práctica para el diseño y medición de competencias profesionales. ESIC Editorial.

Orden ECD/65/2015, de 21 de enero, por la que se describen las relaciones entre las competencias, los contenidos y los criterios de evaluación de la educación primaria, la educación secundaria obligatoria y el bachillerato.

Palmer, A., Montaño, J. J. y Palou, M. (2009). Las competencias genéricas en la educación superior. Estudio comparativo entre la opinión de empleadores y académicos. Psicothema, 21(3), 433-438. http://www.psicothema.com/psicothema.asp?id=3650

Paul, J. J., Teichler, U. y Van der Valden, R. (2000). Higher Education and Graduate Employment. European Journal of Education, 35(2), 309-319.

Poblete, M. y García, A. (Coords.). (2007). Desarrollo de competencias y Créditos transferibles. Experiencia multidisciplinar en el contexto universitario. Universidad de Deusto.

Pozo, J. A. (2017). Competencias profesionales: Herramientas de evaluación: el portafolios, la rúbrica y las pruebas situacionales. Narcea.

Pugh, G. y Lozano-Rodríguez, A. (2019). El desarrollo de competencias genéricas en la educación técnica de nivel superior: un estudio de caso. Calidad en la Educación, (50), 143-179. https://doi.org/10.31619/caledu.n50.725

Recomendación 2006/962/EC, del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, de 18 de diciembre de 2006.

Ruiz, J. M. (2010). Evaluación del diseño de una asignatura por competencias, dentro del EEES, en la carrera de Pedagogía: Estudio de un caso real. Revista de Educación, (351), 435-460. https://tinyurl.com/yztfvmej

Ruiz, Y., García, M., Biencinto, C. y Carpintero, E. (2017). Evaluación de competencias genéricas en el ámbito universitario a través de entornos virtuales: Una revisión narrativa. RELIEVE, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.23.1.7183

Spencer, L. M. y Spencer, S. M. (1993). Competence at work. Models for superior performance. John Wiley and Sons.

Tuning, P. (2006). Una introducción a Tuning Educational Structures in Europe. La contribución de las universidades al proceso de Bolonia. Universidad de Deusto.

Unesco. (2015). Replantear la educación. ¿Hacia un bien común mundial? https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232697

Villa, A. y Poblete, M. (2007). Aprendizaje basado en competencias: una propuesta para la evaluación de las competencias genéricas. Universidad de Deusto.

Villa, A. y Poblete, M. (2011). Evaluación de competencias genéricas: principios, oportunidades y limitaciones. Bordón: Revista de pedagogía, 63(1). https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/BORDON/article/view/28910

Villardón-Gallego, L. (Coord.). (2015). Competencias genéricas en educación superior. Metodologías específicas para su desarrollo. Narcea.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3470-8424

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3470-8424