Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 24, 2022/e23

The Future of Inclusive Education at the University of Bologna: A Survey of Students’ Opinions and Attitudes1

Antonio Luque de la Rosa (*) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7981-029X

Rafaela Gutiérrez Cáceres (*) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5559-2291

(*) Universidad de Almería, Spain

(Received: May 9, 2020; accepted for publishing: October 28, 2020)

Cómo citar: Luque, A. y Gutiérrez, R. (2022). The future of inclusive education at the University of Bologna: A survey of students’opinions and attitudes. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 24, e23, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2022.24.e23.4179

Abstract

This research paper focuses on analyzing the current situation regarding the educational and social inclusion of students with disabilities, based on the point of view of students studying at the College of Education and Learning Sciences in Bologna (Italy). Due to the complexity of the educational situation being analyzed, a descriptive methodological approach was followed, collecting and analyzing quantitative data through a survey. The data sample was obtained incidentally by taking advantage of the research collaboration of one of the authors who was present in Bologna. Overall, the results indicate that these students hold generally positive opinions and attitudes toward the inclusion of disabled students. It should be noted, however, that an improvement in basic training is needed, and that studies should be conducted on educational practice aiming to further develop the implementation of action plans based on academic quality in order to include students with disabilities in higher education.

Keywords: higher education, inclusive education, disabled persons, opinion, attitudes

I. Introduction

In Europe, universities have generally been the educational institutions in which segregation and exclusion of disabled students is most prevalent (Vieira et al., 2002), which contradicts inclusion initiatives that have been ongoing since the 1980s at non-university level institutions.

Nonetheless, tools facilitating disabled students’ access to these types of institutions have been introduced over the years, and the number of disabled students admitted into higher education institutions has increased considerably (Fernández et al., 2019; Ocampo, 2012).

Currently, counseling and support centers have been implemented and made available to the university community, aiming to overcome barriers that impede access to academic curricula and facilitate the progression, participation, and social inclusion of disabled university students (de Camilloni, 2019; Muyor, 2018; Vieira et al., 2002).

This is reflected in the manner in which universities are being organized and run, encouraging all European countries to implement these types of centers within their academic structure to promote the principles of normalization, integration, and inclusion, while concurrently valuing education as a service that should be provided to all citizens (Mangas, 2005). In this sense, the issue is especially relevant in teacher training degrees because it represents the guarantee of promoting inclusion in future teachers and in the education of future generations (Castillo, 2019; Crisol, 2019).

Nonetheless, distinct perspectives have arisen among the various European countries when it comes to promoting student inclusion in universities, which are similar to the differences that arose previously when developing inclusion at all other academic levels. For this reason, this research paper examines the perspective of one country in particular, Italy, which is remarkable by virtue of its ongoing integration since the 1980s. Spain, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Denmark will also be referenced in this paper.

Thus, the aim is to understand the opinions and attitudes of students of higher education in one of the pioneering countries in this field, in order to propose possible actions to improve educational practice.

1.1 Attention devoted to those with disabilities in Italy: a recent history

As previously mentioned, Italy has long been recognized as a leader in the promotion of an inclusive national education system.

Toward the mid-1970s, the country began to see strong development of inclusive social policies, which progressively achieved a wide impact on the overall educational system – more specifically, following the enactment of Italian Law 517 of August 4, 1977.

Subsequently, and with the passing of Italian Law 104 of February 5, 1992, amended by Law 17/1999, the right to education for all disabled students was established not only within childhood education settings, but also within university settings (Art. 12).

This law ensured that all university students with disabilities be provided with technical and educational materials, specialized tutoring, modified exam materials, and a coordinating instructor, as well as monitoring and support throughout all initiatives and proposals regarding inclusion within university settings.

Furthermore, and in accordance with theoretical assumptions that began developing in the 1990s, the implementation of this law reinforced the focus on students with disabilities in all Italian educational systems, including the definition of “disability” itself, which became more inclusive than in the 1970s, reflecting a new level of educational awareness which was, at the time, waning at policy level in Spain (Dettori, 2011).

Since then, an abundance of innovative events have taken place within the Italian educational system that have been essential in promoting social change, allowing for an increased rate of enrollment among disabled students in higher education institutions in Italy.

Nonetheless, and despite these inclusive aspects, the majority of disabled individuals within Italy obtain lower levels of education in comparison to the rest of the population. Seldom do students actually choose to enroll at a university to pursue academic studies. Only 2.55% of all disabled individuals have some type of undergraduate or graduate-level degree, and 49.88% only reach primary education levels, whereas 22.83% do not attain any level of education (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica [ISTAT], 2009).

In this sense, Italy’s inclusion process is not altogether free from criticism, due to limited funding and collaboration between public organizations and society in general, as well as insufficient information and awareness among the university community concerning the implications disabilities have on the learning and development of special needs students (Pascale et al., 2017). There is also a lack of specialized teachers with appropriate levels of education regarding academic and learning support and a lack of training aimed at non-specialized professors.

1.2 Research motives

One of the main obstacles to the inclusion of students within the classroom environment and diversity awareness among students throughout the teaching-learning process is the overall attitude and opinion held by staff members and the rest of the educational community.

Many authors have come to understand that the opinions and attitudes held concerning disabled students are key components in their overall academic success and acceptance within the teaching-learning process (Crispiani, 2016; Macías et al., 2019).

Teachers should be trained and made aware of this in order to understand the advantages that change can have on cultural acceptance, and a general attitude of acceptance and readiness is essential in all educational and social reform processes. The acquisition of commitment skills is a key factor in achieving full inclusion within the classroom environment. Thus, a number of studies have been carried out at the Complutense University of Madrid that have sought to explore the attitudes of future teachers in primary and secondary education toward university students with disabilities. The results, from a sample of 314 students, highlight the fact that students have positive attitudes, although significant differences have been found between the different subgroups of degrees (Macías et al., 2019).

Similar publications exist on students’ opinions and attitudes toward disabled students by authors such as Crispiani (2016), who focuses on the integration of special needs students, and Solís et al. (2019), who focus on the overall acceptance of disabled students.

Many studies have been undertaken regarding inclusive classroom environments at primary and secondary education levels (Castillo, 2019; Crisol, 2019), but the same cannot be said about university level (see, for example, the review by Mellado et al., 2017).

It is therefore helpful to take a look at the study by Ester (2016), which focuses on the opinions and attitudes that university students have toward disabled students, pointing out that if students were to demonstrate a positive attitude toward the educational inclusion of disabled students from the start of their degree course, all students will tend to improve their attitudes toward the end of their academic studies. In relation to this issue, there exists, for example, research by Savia (2019) that shows that inclusive education represents an important challenge in teaching today, highlighting some emerging didactic problems in the Italian context, specifically linked to teachers’ perception of disability and the difficulties of effective collaboration between teachers. Thus, university students often tend to regard academic staff as poorly trained for inclusive teaching and may feel concerned about anonymity when disclosing disabilities, worrying about the way they are perceived by others (Armstrong et al., 2000; Osborne, 2019; Prets & Weber, 2005).

Universities must play a more active role to eliminate barriers to access and participation. Some studies point towards increasing funding, establishing disability offices, and incorporating Universal Design (UD) and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to increase participation (Moliner et al., 2019; Yusof et al., 2019).

Suriá (2011), who carries out a comparative analysis of the attitudes of students toward their disabled classmates, stresses that college students demonstrate more positive attitudes toward their disabled classmates than high school students. The same author also points out that there is an overall higher level of awareness toward disabled individuals among students who interact with special needs classmates, a finding backed up by Bausela (2002) and Sarkar (2016).

Some of the most recent studies on this issue were conducted by Sánchez (2009) in Almería, Spain, and Guzmán and Sánchez (2011) in Tlaxcala, Mexico. Both studies analyzed the opinions and attitudes prevalent in the various departments of the educational community (including those of the disabled students themselves) toward special needs students in countries that are more diverse as far as economic development and cultural acceptance are concerned. Other studies indicate that the inclusion of disabled students in higher levels of education is a task that has yet to be fully accomplished at university level, considering that inclusive society approaches require generalized demands given that diversity in itself is a principle of education that provides a positive contribution to the general population.

Both studies affirm that analyses still need to be carried out on this issue in other Andalusian and Spanish universities, as well as on the causes and motives behind such realities and the specific approaches that are being undertaken in order to confront them. In this regard, the purpose of this study is to complement previous studies in which we participated as part of the research team within the University of Almería and the University of Tlaxcala, contrasting the results obtained in these two universities with those obtained in Bologna (Italy). Italy is a European country that, like Spain, has a long history of educational inclusion and which, after having undergone an initial “ideological” stage of educational inclusion, has also decided to implement this idea within the structures and operations of the country’s universities, which requires the support of rigorous and pivotal research that contrasts this idea with other experiences in order to reflect on, elaborate on, and improve the quality of these educational practices.

For all the above reasons, and despite the lack of previous studies based on the current situation in Italian higher education, the following study is crucial in analyzing the current situation concerning the educational and social inclusion of disabled students, from the perspective of students from the University of Bologna, in order to gain insight into this issue within the European Higher Education Area to promote the inclusive process demanded by government agencies.

II. Methodology

Based on the previous theoretical assumptions and the aforementioned research, the main objectives of this paper include:

Studying students’ opinions about the educational and social inclusion of disabled students at the University of Bologna.

Examining students’ attitudes toward disabled students and their inclusion at the University of Bologna.

Analyzing the opinions and attitudes of these students based on the following variables: age group, gender, and experience with the inclusion of disabled students in universities.

Once these objectives had been established, research was conducted following a descriptive methodological approach, given the complex nature of the educational situation being analyzed. Taking into account the need to carry out an analysis based on the actual institution in which educational services are being developed and offered to students at the University of Bologna, one part of the methodology involves collecting and describing quantitative data concerning the object of study, whereas the other part involves analyzing ideas and attitudes towards educational inclusion based on various variables: age group, gender, and experience with the inclusion of disabled students in universities.

In line with the methodology, and based on the established objectives, the data sample was obtained incidentally by taking advantage of the research collaboration of one of the authors who was present in Bologna. This data sample was collected from a group of students who voluntarily came together and collaborated with one another in order to complete the questionnaires.

A total of 272 students from the College of Education and Learning Sciences at the University of Bologna, who are enrolled in a bachelor’s degree in primary education sciences, participated in this study, and 82% of those surveyed were in their second year of studies.

The average age of these students was 22.46 years (SD: 4.59; range: 19-41 years old), 88.9% were between the ages of 19 and 26, and 94.4% of survey respondents were women. Among those surveyed, 41 students have had classmates with some type of physical or mental disability, but only 19 claim to have received any type of information regarding the treatment given to disabled students.

In order to determine opinions and attitudes regarding disability and inclusion, a survey was conducted with questionnaires administered to a set of students at the University of Bologna. This data collection technique was developed in response to specific needs within the Italian educational system, based on an adaptation of the “Questionnaire about Opinions and Attitudes Towards the Educational and Social Inclusion of Disabled Students” (Sánchez, 2009).

It should be noted that, given the exploratory and comparative nature of the objectives, this technique is considered useful for a detailed approach to the object of study. The knowledge gained in this study is necessary to progress towards identifying defining social and cultural factors in order to fully analyze the issue in future research.

This survey involves a technique that is widespread in social research, whereby data is obtained through questionnaires based on the opinions of a set group of individuals (Herrera, 2017; Maxwell, 2019). This, in turn, allows for these opinions to be converted and given a sort of numeric value in order to be statistically analyzed and used to describe the results.

The original version of this questionnaire (Sánchez, 2009) was prepared and designed based on the guidance of experts in this field (Perines & Murillo, 2017; Torres et al., n.d.). Once the first version was drafted, it was given to educational experts for revision and testing, which resulted in subsequent versions. Prior to this survey, a pilot study was conducted involving students from the University of Almería, in which the final version was drafted, with a high level of reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: .9). The questionnaire used in this study within the Italian setting has been modified and adjusted based on this final version, and has been named “Questionnaire on the Analysis of Inclusion in the University, Students’ Sector” (CAIU.E.Bolonia). It maintains an acceptable level of internal consistency for this type of research, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding .8 in all aspects (Huh et al., 2006).

In order to facilitate the analysis and comprehension of the results obtained, and taking into consideration the theoretical assumptions mentioned in the previous section, while concurrently following the validation process by means of an expert review resulting in an agreement level among judges of 97% (Perines & Murillo, 2017), all of the items in the questionnaire were assessed and categorized, and each item was assigned to corresponding analytical categories, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Analysis categories and item categorization

| Category | Definition | Items | Reliability level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic modifications | Opinions and attitudes students have about academic modifications concerning disabled students at the University of Bologna. | 1, 3, 7, 9, 15, 20, 24, 25, 26, 34 | 0.84 |

| Acceptance | Opinions and attitudes students have toward the inclusion of disabled students at the University of Bologna. | 2, 4, 5, 6, 17, 21, 23, 29 | 0.94 |

| Overall level of training of university staff members | Opinions and attitudes students have with regard to the training received by university staff members concerning the inclusion of disabled students. | 8, 10, 12, 32, 35, 36, 37, 39 | 0.89 |

| University services | Opinions and attitudes students have regarding university services that support the inclusion of disabled students. | 11, 13, 14, 16, 18, 19, 22, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 38, 40 | 0.87 |

In an effort to analyze the data in a merely descriptive manner, the four different levels of selection – depending on which item is chosen in the questionnaire – have been given numeric values. Thus, “strongly disagree” equals 0 points, “disagree” is equal to 1 point, “agree” is equal to 3 points, and “strongly agree” is equal to 4 points. Two values have also been established in order to condense the four choices into two categories, namely a) rejection, including choices 1 (strongly disagree) and 2 (disagree); and b) approval, including choices 3 (agree) and 4 (strongly agree).

Throughout this data analysis, descriptive statistics were used, including frequency distribution, percentages, averages, and standard deviation. Similarly, and taking into account items strictly by their ordinal value, Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis’s U tests were applied, which are non-parametric statistics that compare the groups established in accordance with the nominal variable (age group; gender; whether or not they have or have had classmates with disabilities; whether or not they have received any type of information regarding the presence of disabled students within the classroom).

III. Results

3.1 Overall descriptive analysis

The obtained results as a whole produced an overall average value of 2.72 (close to the “agree” value), indicating a considerable level of acceptance among university students, with a moderate variation range (SD: .77).

Item 23 is worth noting, given that 94.4% of those surveyed state that they either agree or strongly agree that the presence of disabled students does not impede the overall academic level (M: 3.42; SD: .59).

According to the results of item 6, 90.2% of those surveyed agree or strongly agree that the presence of disabled students does not hinder their own learning process (M: 3.33; SD: .69).

A similar trend is observed with regard to item 17, where 84.7% of those surveyed agreed that the presence of disabled students within the classroom environment does not cause any problems or difficulties (M: 3.22; SD: .73).

Another interesting finding is observed in item 5, where 88.9% of students express their interest in wanting to interact with disabled students, were this interaction to be beneficial to disabled students (M: 3.27; SD: .69).

Contrary to the positive results regarding the inclusion of disabled students within higher education environments, 83.3% of surveyed students feel that their disabled classmates face more difficulties in successfully completing their studies at the University of Bologna due to limited adapted resources (item 3; M: 1.80; SD: .78).

Similarly, and according to item 35, only 36.1% of students either agree or strongly agree that course curricula comprise sufficient credit hours to train teachers on how to give appropriate attention to disabled students within academic settings (M: 2.20; SD: .76). It is also worth noting that 58.2% of students feel as if they are not informed of the presence of disabled classmates in their classrooms beforehand (item 12; M: 2.23; SD: .88).

Lastly, by taking into account standard deviation measures, item 1 (“University access is provided to disabled students”) and item 21 (“The presence of disabled students within the classroom environment is beneficial to all students”) stand out in terms of the low standard deviations (SD: .56 and .68, respectively), and the majority of those surveyed agreed with these statements.

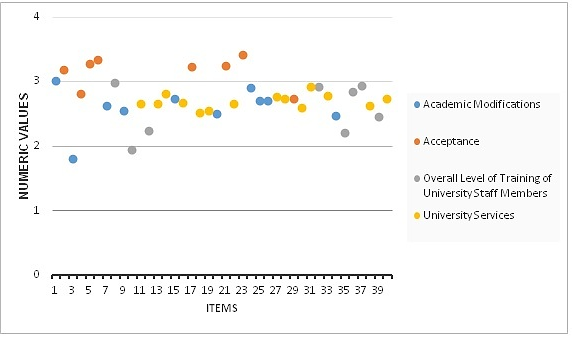

3.2 Analyses according to category and type

The following analysis is given based on the category group of each item, as outlined above. These category groups relate to various aspects concerning disabled students attending universities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Descriptive results by category

Academic modifications. For this category, the overall average numeric value is 2.59 (SD: .77), which comes close to the numeric value of “agree.” Regarding the items referred to as “modifications”, item 1 has an overall higher average, with 84.8% of students agreeing that disabled students are provided with access to universities.

Consistent with this result is the fact that 76.4% of those surveyed feel that disabled students have the same opportunities and possibilities to progress as do the rest of students (item 24). Furthermore, 87.5% believe that the level of studies and degrees obtained by disabled students imply overall competence with regard to their professional development (item 26). Nonetheless, when those surveyed were asked whether or not disabled students faced more difficulties in finishing their academic studies due to a lack of resources that adequately met their needs, interestingly, 83.3% indeed agreed with this statement (item 3).

Acceptance. With regard to the category labeled “acceptance”, which was understood to be one of the basic prerequisites for the inclusion of disabled students at university level, the overall average was 3.14 (SD: .71), which corresponds to the numeric value of the response “agree.” With regard to all of the items constituting this category as a whole, items 23 and 6 in particular stand out as exceeding the average numeric value (M: 3.41 and 3.33; SD: .59 and .69, respectively). Furthermore, 94.4% of students claim that the presence of disabled students does not negatively impact the overall academic level (item 23). In the same vein, 90.2% feel that their presence does not cause any type of obstacle to student learning (item 6).

It is important to note that item 29 was the least positively valued of all items, and only 77.8% consider that there is indeed adequate communication between disabled students and their classmates. This communication is essential in supporting the overall inclusion of disabled students at university level. In addition, 62.5% of students believe that they do not have any problems or difficulties interacting with disabled students (item 4).

Overall level of training of university staff members. In this category, the average numeric value was 2.55 (SD: .82), and item 8 was the most notable item in terms of overall average. All in all, 77.8% of students believe that positive activities geared toward disabled students and their inclusion within the university are indeed promoted. Furthermore, 79.1% of students feel that basic training and education encompasses special attention geared toward disabled students (item 37), and 73.6% report that awareness within the school environment regarding services tailored to disabled students’ needs is indeed promoted. Despite this, only 23.6% of students claim to have received some type of training encouraging the inclusion of disabled students within their university (item 10).

University services. Lastly, with regard to the category entitled “University Services”, the overall numeric average was 2.68 (SD: .77), which comes close to the numeric value of the “agree” option. Item 31 is of substantial value, in that 76.4% of those surveyed declare that regulations dealing with the rights and responsibilities of disabled students are fully met. Furthermore, 73.6% of students believe that adequate resources do indeed exist to facilitate the active integration of disabled students within the university setting (item 14). Nevertheless, according to 43.1% of students, there is no specific type of regulation concerning the attention given to disabled students at the University of Bologna (item 18). There is also a lack of adequate resources with regard to the development of access to academic curricula that have been tailored to the needs of disabled students (item 19).

3.3 Comparative analyses

The following section reveals the most pertinent results obtained from the comparative analysis addressing these aspects with respect to the following variables: gender, experience regarding the inclusion of disabled students in universities, and age group (see Table 2).

Table 2. Overall comparative results

| Category | Gender | Age | Previous experiencea | Previous informationb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | <= 21 | 22-26 | 27-41 | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Academic modifications | 2.77 | 2.32 | 2.65 | 2.62 | 2.63 | 2.65 | 2.57 | 2.66 | 2.38 |

| Acceptance | 2.97 | 3.18 | 3.14 | 3.21 | 3.28 | 3.19 | 3.06 | 3.17 | 3.15 |

| Overall level of training of university staff members | 2.34 | 2.56 | 2.54 | 2.65 | 2.39 | 2.57 | 2.43 | 2.55 | 2.47 |

| University services | 2.36 | 2.71 | 2.66 | 2.75 | 2.73 | 2.69 | 2.65 | 2.70 | 2.47 |

| Nota: aPrevious experience with disabled classmates. bPrevious information regarding disabled students. | |||||||||

By comparing all of the obtained numeric averages, and by taking into consideration all of the categories regarding the educational and social inclusion of disabled students as a whole, the category entitled “Acceptance” was the most favored category, especially among female students and older students. By contrast, least valued was the category relating to the training received by the university community and personnel regarding the inclusion of disabled students, especially among male students and students between the ages of 19 and 21.

In order to elaborate upon the comparative analysis of the opinions and attitudes of students based on the aforementioned variables, and keeping in mind that this study does not follow parametric assumptions (normality, homoscedasticity…), nonparametric statistics were utilized based on the Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples and the Kruskal-Wallis test. The following results were most pertinent.

With regard to the relationship between gender and the opinions and attitudes regarding university-level inclusion of disabled students, female opinions were generally more positive with regard to the statements included in the following items of the questionnaire (p < .05, Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples):

- Item 22: Economic efforts are increased with regard to support provided to disabled students (.02).

- Item 27: Students, especially those with some type of disability, are aware of the required competences within each degree program/major before beginning the registration process (.005) (100 % of surveyed men disagree) (.01).

- Item 33: Infrastructural modifications exist within the university to accommodate the various types of disabled students (.03).

According to the results, students who have received some type of information from the University of Bologna with regard to the presence of disabled students, express a significant level of disapproval toward the following statements (p <.05, Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples):

- Item 25: University tests and exams provide the necessary resources and modifications required to satisfy the needs of disabled students (.03).

- Item 27: Students, especially those with some type of disability, are aware of the required competences within each degree program/major before beginning the registration process (.01).

An analysis of data distribution by age group shows that those between the ages of 22 and 26 are particularly noteworthy in item 7 (“The objectives and content are identical – or the same – for all students”) and item 19 (“The university is equipped with the necessary tools to address any type of modification that may need to be implemented in order to facilitate access to academic curricula for disabled students”) (.05 and .01, respectively; Kruskal-Wallis test).

Moreover, the older age group (comprising students between the ages of 27 and 41) stands out in item 21 (“The university is equipped with the necessary tools to address any type of modification that may need to be implemented in order to facilitate access to academic curricula for disabled students”) (.01; Kruskal-Wallis test).

Lastly, and taking into consideration the variable regarding whether or not students have had classmates with disabilities, it has been found that there are differences among students concerning the opinions and attitudes held toward the inclusion of disabled university students. In this regard, students who have peers with disabilities express a significant level of disagreement with the following statements (p <.05, Kruskal-Wallis test):

- Item 17: The presence of students with disabilities in the classroom poses problems and difficulties (.04).

- Item 23: The presence of students with disabilities in the classroom leads to a reduction of the academic level (.05).

IV. Discussion

Following the analyses, and taking into consideration the overall descriptive results, it can be asserted that students who major in primary education studies at the University of Bologna hold generally positive opinions and attitudes toward the social and educational inclusion of disabled students.

An analysis by category leads to the conclusion that the category “Acceptance” prevails over all others, given that a generally positive attitude toward the educational inclusion of disabled students was found among students at the University of Bologna. Above all, they consider that disabled students within the classroom environment neither hinder the overall academic level (item 23) nor limit the learning process of students (item 6). This illustrates the high level of acceptance of disabled students, which goes beyond the presumed obstacles or limitations resulting from the implementation of modifications tailored to their academic needs.

With regard to the category involving student opinions and attitudes toward services offered at the university that promote the inclusion of disabled students, the majority of those surveyed report that the university indeed abides by the regulations relating to rights and responsibilities concerning the inclusion of disabled students (item 31); the university is recognized as thoroughly fulfilling established rules, and overall, completing tasks well.

In the analysis between the different subgroups, it is worth noting that, even though the larger subgroups in terms of age and gender tend to display more inclusive attitudes and opinions, some of the smaller subgroups (such as those who have had some type of experience with disabled classmates or who have previous knowledge of this subject) are at an advantage due to the fact they hold more realistic beliefs in terms of inclusion. This may actually be indicative of the high educational values (in theory or through experience) placed on the creation of supportive and dynamic initiatives aimed at social progress.

With regard to the results of these contrasts between subgroups, the sample is inadequate in providing concrete, contrasting opinions, given the high prevalence of certain groups within the sample of participants (such as women, students between the ages of 22 and 26, and students with little experience with disabled classmates and/or limited information/training). This will require future, stratified sampling and research.

Despite these limitations, it should be noted that this research paper provides a general view on the multiple aspects that make up an overall sense of inclusion within the university setting, based on a specific academic program, and it serves as a means of comparison with data obtained by other universities from different countries that used similar tools and sources.

Overall, a comparison of the results of this study (University of Bologna) with results from other similar studies that used the same type of data collection methods (or slightly modified methods, as is the case with the Mexican study) and the same type of sample, as is the case with the University of Almería (Sánchez, 2009) and the University of Tlaxcala (Guzmán & Sánchez, 2011), shows that the results obtained in the Italian study (M: 2.72; SD: .77) are similar to those obtained in previous studies (Almería: M: 2.27; SD: .65; Tlaxcala: M: 2.81; SD: .79).

However, the following differences were observed between these contexts. Firstly, the overall average favorable opinion toward inclusion is slightly higher in Bologna than in Almería (Sánchez, 2009); b) the Mexican results continue to show higher figures than the European results in terms of the number of students with receptive attitudes toward integrative measures to ensure efficient integration of disabled students within the university setting.

Comparing the results obtained in this study with those of a similar study carried out at the University of Almería in greater detail (Sánchez, 2009) shows that both student groups show similar tendencies in their agreement with the following aspects: promoting positive attitudes toward all disabled students; demonstrating willingness to facilitate disabled students’ access to – and integration within – the college; requiring that the university provide adequate resources; increasing economic efforts in terms of improving the academic support given to disabled students and promoting more positive attitudes toward developing this initiative; the lack of flexibility in allowing disabled students to acquire the required skills throughout their degrees; and requiring that the same advancement opportunities and possibilities be offered to disabled students, thereby defending the right to equal opportunity.

Nonetheless, there are certain discrepancies in the following aspects: the need to provide the university with a central unit or department in charge of providing counseling and tutoring services to disabled students and all university staff (higher willingness in Almería); a positive attitude toward the inclusion of disabled students within the classroom (higher willingness in Bologna); and a clear arrangement in providing adequate training to facilitate disabled students’ attendance within the classroom environment (higher willingness in Almería).

Furthermore, by comparing both studies, it can be noted that there are some differences among students surveyed at the University of Bologna based on gender, age, and whether or not they have received some type of information regarding the presence of disabled students. However, these differences were more profound in Bologna, given that the number of students who claimed to have received some type of related training is very limited.

Finally, the comparative analysis between subgroups shows that, based on the variable concerning whether or not students have ever had disabled classmates, there are clearly significant differences in the opinions or attitudes held by students of both universities (Almería and Bologna).

In view of all the data, it can be noted that while inclusion policies are contributing to students’ awareness of this subject in all the countries studied (albeit with slight differences depending on the exact issue being analyzed), experiencing inclusion in any field (including disability) provides the necessary attitudinal change that guarantees the construction of a “world for all.”

V. Conclusions

In light of these results, it can be asserted that, in general terms, although institutional approaches are theoretically progressing at a decent pace, the opinions and attitudes regarding the inclusion of disabled students in higher education institutions are yet to be substantial and shared as a whole with regard to the aspects that would otherwise form an all-around “inclusive university” in Bologna (as is the case with the other aforementioned settings). This does not completely disregard the generally positive tendencies and attitudes shown by students, which may help explain the lengthy path toward academic integration that is being experienced in Italy.

This should lead us to reflect on the need to increase awareness and sensitivity policies in these communities, and establish aspects that promote general inclusion in student curricula and faculty training programs.

According to the reports analyzed, and in order to establish a more elaborate representation of data, other Spanish and European universities would need to analyze the same issue and specific measures and approaches would need to be taken in order to confront this reality. They would also need to make proposals to improve the academic and social inclusion of students with some type of specific academic need due to a disability.

The overall purpose of such research would be to identify a general vision that would provide further information on suitable aspects in promoting an inclusive culture, while concurrently working to maintain student awareness with regard to inclusion within university settings. In order to achieve this objective, it is essential to develop standards and good practice guidelines concerning all of the academic situations that may represent any type of unequal opportunity for disabled students (see, for example, Bravo & Santos, 2019; Díez et al., 2011).

Furthermore, information and communications technology (ICT) will need to be implemented in university classrooms in order to promote and facilitate the inclusion of disabled students within university settings. Technology training allows users to overcome physical barriers, time constraints, and obstacles related to the cognitive abilities of certain disabled students.

These conclusions urge us to consider international challenges in universities, such as the clarity of the idea of inclusion (Armstrong et al., 2000; Prets & Weber, 2005); the establishment of regulations, plans, and programs that guarantee equal opportunities as well as support services and specific resources; the awareness of the university community; and the establishment of coordination mechanisms between the different internal services (Moliner et al., 2019).

There are also some intangible barriers, such as attitudinal and pedagogical barriers in students and teachers (Bausela, 2002; Sarkar, 2016). The challenge faced by the University of Bologna is to develop the pedagogical competences of teachers, as an opportunity to innovate in teaching strategies that enable higher education professionals to strengthen their practice from an inclusive pedagogical perspective.

All these reasons lead us to stress that progression toward the European Higher Education Area would require new collective settings and points of contact between the university community and any association movements working toward the inclusion of disabled students. In this respect, analyses of current real-life situations involving comparative approaches and the promotion of joint actions are essential in order to take the necessary measures and steps toward the inclusion of disabled students within higher education institutions and society as a whole.

Referencias

Armstrong, F., Armstrong, D., & Barton, L. (2000). Inclusive education: policy, contexts, and comparative perspectives. Fulton.

Bausela, E. (2002). Atención a la diversidad en la educación superior [Addressing diversity in higher education]. Profesorado, Revista de Curriculum y Formación del Profesorado, 6(1), 1-11.

Bravo, P., & Santos, O. (2019). Percepciones respecto a la atención a la diversidad o inclusión educativa en estudiantes universitarios [Perceptions of the approach to diversity or educational inclusion in university students]. Sophia, colección de Filosofía de la Educación, 26, 327-352. https://doi.org/10.17163/soph.n26.2019.10

Castillo, N. M. (2019). Educación inclusiva: contradicciones, debates y resistencias [Inclusive education: Contradictions, debates and resistance]. Praxis Educativa, 23(3), 4, 1-10.

Crisol, E. (2019). Hacia una educación inclusiva para todos. Nuevas contribuciones [Towards inclusive education for all. New contributions]. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado, 23(1), 1-9. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/profesorado/article/view/72108

Crispiani, P. (2016). Storia della pedagogia speciale [History of special pedagogy]. Edizioni ETS.

de Camilloni, A. R. (2019). La inclusión de la educación experiencial en el currículo universitario [Including experiential education in the university curriculum]. Universidad Nacional del Litoral.

Dettori, F. (2011). La integración de alumnos con necesidades educativas especiales en Europa: el caso de España e Italia [The integration of students with special educational needs in Europe: The case of Spain and Italy]. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 4(3), 67-78. http://www.ujaen.es/revista/rei/linked/documentos/documentos/14-5.pdf

Díez, E., Alonso, A., Verdugo, M.A., Campo, M., Sancho, I., Sánchez, S, Calvo, I., & Moral, E. (2011). Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior: estándares e indicadores de buenas prácticas para la atención a estudiantes universitarios con discapacidad [European Higher Education Area: Standards and indicators of good practices to serve university students with disabilities]. INICO.

Ester, A. T. (2016). La educación intercultural como principal modelo educativo para la integración social de los inmigrantes [Intercultural education as the main educational model for the social integration of immigrants]. Cadernos de Dereito Actual, (4), 139-151. http://www.cadernosdedereitoactual.es/ojs/index.php/ cadernos/article/view/75

Fernández, A. C., Domínguez, C. R., & Perea, L. G. (October 2019). Análisis de los planes de atención a la diversidad en las universidades andaluzas [Addressing diversity in Andalusian universities]. Conference Proceedings CIVINEDU 2019: 3rd International Virtual Conference on Educational Research and Innovation, Madrid. REDINE. https://www.civinedu.org/conference-proceedings-2019/

Guzmán, J., & Sánchez, A. (2011). La integración educativa y social de estudiantes con discapacidad en las instituciones de educación superior del estado de Tlaxcala (México) [The educational and social integration of students with disabilities in higher education institutions in the state of Tlaxcala]. Universidad de Tlaxcala.

Herrera, J. (2017). La investigación cualitativa [Qualitative research]. UDGVirtual.

Huh, J., Delorme, D. E., & Reid, L. N. (2006). Perceived third-person effects and consumer attitudes on prevetting and banning DTC Advertising. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 40(1), 90-116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00047.x

Istituto Nazionale di Statistic. (2009). La disabilità in Italia. Il cuadro Della statistica ufficiale [Disability in Italy. The framework of oficial statistics]. ISTAT.

Law 104 of February 5, 1992. Legge-quadro per l’assistenza, l’integrazione sociale e i diritti delle persone handicappate [Framework law for assistance, social integration and the rights of handicapped people].

Law 17 of January 28, 1999. Integrazione e modifica della leggequadro 5 febbraio 1992, n. 104, per l’assistenza, l’integrazione sociale e i diritti delle persone handicappate [Integration and modification of framework law of February 5, 1992, no. 104, for assistance, social integration and the rights of handicapped people].

Law 517 of August 4, 1977. Norme sulla valutazione degli alunni e sull’abolizione degli esami di riparazione nonché altre norme di modifica dell’ordinamento scolastico [Rules on the assessment of pupils and the abolition of remedial exams as well as other rules for amending the school system].

Macías, M. E., Aguilera, J. L., Rodríguez, M., & Gil, S. (2019). Un estudio transversal sobre las actitudes de los estudiantes de pregrado y máster en ciencias de la educación hacia las personas con discapacidad [A cross-sectional study on the attitudes of undergraduate and graduate students of educational sciences toward individuals with disabilities]. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 22(1), 225-240. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.22.1.353031

Mangas, A. (2005). La constitución europea [The European constitution]. Revista del Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales, 57, 570-581.

Maxwell, J. A. (2019). Diseño de investigación cualitativa [Qualitative research design]. Gedisa.

Mellado, M. E., Chaucono, J. C., Carlos, J., Hueche, M. C., & Aravna, O. A. (2017). Percepciones sobre la educación inclusiva del profesorado de una escuela con Programa de Integración Escolar [Teacher perceptions of inclusive education at a school with a School Integration Program]. Revista Educación, 41(1), 119-132. https://doi.org/10.15517/REVEDU.V41I1.21597

Moliner, O., Yazzo, M. A., Niclot, D., & Philippot, T. (2019). Universidad inclusiva: percepciones de los responsables de los servicios de apoyo a las personas con discapacidad [Inclusive university: Perceptions of disability support services]. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 21, e20, 1-10. https://redie.uabc.mx/redie/article/view/1972

Muyor, J. M. (2018). Nuevos significados de la discapacidad [New meanings of disability]. Acciones e investigaciones sociales, (39), 33-55. https://doi.org/10.26754/ojs_ais/ais.2018393231

Ocampo, A. (2012). Inclusión de estudiantes en situación de discapacidad a la educación superior. Desafíos y oportunidades [Inclusion of disabled students in higher education. Challenges and opportunities]. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 6(2), 227-239. http://www.rinace.net/rlei/numeros/vol6-num2/art10.html

Osborne, T. (2019). Not lazy, not faking: Teaching and learning experiences of university students with disabilities. Disability & Society, 34(2), 228-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1515724

Pascale, L. D., Carrión, J. J., & Fernández-Martínez, M. D. (2017). El estatus y roles de la familia en la escuela inclusiva en Italia: el caso de un instituto profesional [Family roles and status in inclusive schools in Italy: The case of one professional institution]. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 10(2), 181-194. https://revistaeducacioninclusiva.es/index.php/REI/article/view/338

Perines, H., & Murillo, F. J. (2017). ¿Cómo mejorar la investigación educativa? Sugerencias de los docentes [How can educational research be improved? Teacher suggestions]. Revista de la Educación Superior, 46(181), 89-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resu.2016.11.003

Prets, C., & Weber, H. (2005). Intégration et handicaps: la situation européenne [Integration and disabilities: The situation in Europe]. Reliance, 16, 54-60. https://www.cairn.info/revue-reliance-2005-2-page-54.htm

Sánchez, A. (2009). La integración educativa y social de los estudiantes con discapacidad en la universidad de Almería [Educational and social integration of students with disabilities in the University of Almería]. Universidad de Almería.

Sarkar, R. (2016). Inclusive university: A way out to ensure quality, equity, and accessibility for students with disabilities in higher education. International Journal of Advanced Research, 4(4), 406-412. http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/312

Savia, G. (2019). Educación inclusiva en Italia. Diseño universal para el aprendizaje y la práctica reflexiva de los docentes para mejorar la enseñanza [Inclusive education in Italy. A universal design for learning and reflective practice for teachers in order to improve teaching] [Doctoral thesis]. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain.

Solís, P., Pedrosa, I., & Mateos-Fernández, L. M. (2019). Assessment and interpretation of teachers’ attitudes towards students with disabilities. Cultura y Educación, 31(3), 576-608. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2019.1630955

Suriá, R. (2011). Análisis comparativo sobre las actitudes de los estudiantes hacia sus compañeros con discapacidad [A comparative analysis of students’ attitudes toward classmates with disabilities]. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 9(1), 197-216. http://hdl.handle.net/10045/25924

Torres, M., Paz, K., & Salazar, F. G. (n.d.). Métodos de recolección de datos para una investigación [Data collection methods for research]. Boletín electrónico de la Facultad de Ingeniería de la Universidad Rafael Landívar, (3), 1-21. http://fgsalazar.net/LANDIVAR/ING-PRIMERO/boletin03/URL_03_BAS01.pdf

Vidal, J., Díez, G. M., & Vieira, M. J. (2002). Oferta de los servicios de orientación en las universidades españolas [Range of guidance services available in Spanish universities]. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 20(2), 431-448. https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/99001

Yusof, Y., Chong C. C., Hillaluddin, A. H., Ahmad, F. Z., & Saad, Z. M. (2019). Improving inclusion of students with disabilities in Malaysian higher education. Disability & Society, 35(7), 1145-1170. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1667304