Revista Electronica

de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 17, No. 2, 2015

Multimedia Instruction & Language Learning Attitudes:

A Study with University Students1

Jesús Izquierdo (1) jesus.izquierdo@mail.mcgill.ca

Daphnée Simard (2) simard.daphnee@uqam.ca

María Guadalupe Garza Pulido (1) gpegarza21@gmail.com

(1) Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco

(2) Université du Québec à Montréal

(Recibido: 3 de julio de 2013; Aceptado para su publicación: 12 de enero de

2015)

Abstract This study examined the effects of two types of Multimedia Instruction (MI) and learners’ second language (L2) proficiency on language learning attitudes. During four weeks, university learners of French received MI on the distinctive use of the perfective and the imperfective past in one of the four following conditions: learners with low L2 proficiency level exposed to MI with (n=17) or without language awareness tasks (n=17), and learners with intermediate L2 proficiency level exposed to MI with (n=14) or without language awareness tasks (n=28). Before and after the experiment, participants completed the Attitude/Motivation Test Battery (AMTB). Non-parametric analyses revealed a positive enhancement of classroom-related attitudes only among intermediate learners exposed to MI without Language Awareness Tasks. Nevertheless, the results showed similar as well as stable attitudes towards language learning in all the experimental conditions.

Keywords: Second language learning, multimedia instruction, learner attitudes.

I. Introduction

Multimedia instruction (MI) can be defined as instructional

procedures that integrate online or onsite computer environments where the combination

of text, sound, images, and interactivity in learning tasks helps students advance

their second language (L2) knowledge (Plass & Jones, 2005). To favour MI

language education, the positive attitudes that L2 learners show toward the

Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) materials have

been emphasized (e.g., Leakey & Ranchoux, 2006; Sagarra & Zapata, 2008).

In previous research, the examination of learner attitudes has constituted an

ad hoc component, where the conceptualization and design have not directly

built upon the relationship between MI and L2 attitudes.

For research to be informative with respect to the relationship between computers

and learner attitudes, its constructs and design should be directly linked to

previous L2 theoretical and empirical work so as to address the variables influencing

the attitudinal results (see Reeder, Heift, Roch, Tabyanian, & Gölz, 2004).

In this regard, the results from CALL research point out

the need to address different types of variables that can interact in MI

(see Ayres 2002; Mahfouz & Ihmeideh, 2009). While the examination of all the

variables intervening in CALL instruction is difficult,

if indeed it is even possible (Reeder et al. 2003, p. 261), this study will

address the following three variables.

The main variable of this study relates to the type of L2 attitudes on which

MI can have an influence. While there is not yet a consensus

on the attitudes to explore (e.g., Ayres, 2002; Mahfouz & Ihmeideh, 2009; VanAacken,

1999), some L2 investigations have built upon Gardner's (1985a, 1985b) socio-educational

model of learner motivation and attitudes. This model differentiates between

learner attitudes towards the learning of a particular group's language, the

L2 learning itself, and the learning context. The first attitude type is part

of the integrativeness construct and reflects the learners’ desire

to acquire a L2 to integrate into the L2 community. The second attitude type

includes attitudes toward L2 learning, which are part of the learner motivation

to learn the L2. These attitudes denote learners’ willingness

to make efforts during the learning process. Finally, attitudes toward the

L2 learning context refer to learner appreciation of the course instructor

and the French course.

Congruent with this differentiation, in a meta-analysis conducted with 75 research

samples including 10,489 participants, Masgoret and Gardner (2003) found a strong

correlation between learners’ motivation, which involves attitudes toward L2

learning, and L2 achievement. Weaker correlations were found between L2 achievement

and integrativeness, which reflects learner attitudes toward the L2 speakers,

and between L2 achievement and attitudes toward the learning context (see also

Gardner, Lalonde, & Moorcroft, 1985; Gardner & MacIntyre, 1985; Gardner, Tremblay,

& Masgoret, 1997). Based on these results, various authors highlight the importance

of exploring in MI the attitudes that strongly correlate

with L2 learning (Ayres, 2002; Mahfouz & Ihmeideh, 2009; VanAacken, 1999).

The second variable to explore during MI is the type of

instruction that learners receive. Following Krashen’s (1992, 1994) comprehensible

input hypothesis, MI research has provided learners with

rich exposure to the L2 in meaning-based tasks built upon different media features

(Plass & Jones, 2005, p. 469). Studies have examined grammar and lexical growth,

for instance, when the target linguistic elements are visually enhanced through

textual highlights, glosses, captioning or hyperlinks in the production and

comprehension tasks or when the completion of the multimedia tasks pushes learners

to process the target L2 elements for meaning (Izquierdo, 2014).

With the exception of a few studies (e.g., Sanz, 2004; Sanz & Morgan-Short,

2004), learners’ exposure to MI has been fostered without

tasks that overtly draw learner attention to the L2 targets. Yet, in L2 acquisition

research, language awareness tasks (LATS), or

tasks designed to overtly raise learner awareness of the relationship between

the L2 forms and their communicative function, are recommended (Morales & Izquierdo,

2011). While several issues remain to be addressed (Ellis, 2001; Simard & Wong,

2004), L2 acquisition reviews and meta-analyses indicate that L2 instruction

including LATS leads to stronger L2 learning effects than

L2 instruction without LATS (e.g., Lyster, 2004; Spada

& Tomita, 2010). However, a distinction should be drawn between LATS

and computer-based drills (Chapelle, 1998, 2001). LATS

raise learners’ awareness of the form and function of L2 forms in meaning-oriented

tasks. They constitute a step within an instructional sequence providing learners

with sustained exposure to L2 form-meaning (Lyster, 2004; Simard & Wong, 2004).

Drills, however, are isolated computer-based decontextualized mechanical exercises,

which do not foster the communicative value of L2 forms (Chapelle, 2001). Krashen

(1992, 1994), moreover, has stated that L2 instruction including overt attention

to L2 grammar is detrimental for learning, as it increases learner anxiety and

decreases learning interest.

Finally, the third variable of this study is the level of L2 competency at which

learners receive MI. In studies exploring MI

and L2 lexical development, the ad-hoc examinations of learner attitudes

have pointed to similar attitudes across all learners irrespective of L2 knowledge

differences. Kawauchi (2005), for instance, examined the effects of computer-enhanced

lexical growth among learners from two L2 levels. The analyses of the participants'

gains pointed to better scores among learners in the lowest level; yet, learners'

appreciation of the computer instruction was positive and similar irrespective

of their L2 level (see also De la Cruz & Izquierdo, 2014).

In contrast to these attitudinal results, a recent study revealed that L2 learners’

grammar mastery influenced interest in MI task completion

(Izquierdo, 2007). Based on the patterns of L2 French past-tense development

(see Bardovi-Harlig, 2000; Harley, 1992), Izquierdo (2007) exposed learners

from two past-tense proficiency levels to one of two sets of MI

experimental materials, including four one-hour lessons teaching the perfective

and imperfective past: passé composé and imparfait, respectively. Through

meaning-based tasks, Set 1 exposed learners to past-tense forms representing

past-tense emerging use. These forms require the perfective with telic predicates,

whose meaning implies that the action must come to an end in order to occur

(e.g., to eat an apple, to arrive, to open a book), and the imperfective with

atelic predicates (e.g., to be Mexican, to watch TV, to

walk in a park), which are verbal predicates denoting a permanent state or actions

that do not have an inherent end (Andersen, 1991, 2002), as Example 1 illustrates.

Example 1. Emerging use of L2 French past tense

| 1.a. Il s’est reveillé | He wake+perfective up | |

| 1.b. Il a courru deux kilomètres | He run+perfective two kilometres | |

| 1.c. Il était content | He be+imperfective happy | |

| 1.d. Il est resté à la maison | He stay+imperfective home |

Set 2 included the same meaning-oriented

multimedia tasks, but required an advanced use of the perfective and imperfective

forms. In these forms, the learners mark the perfective past with atelic predicates

and the imperfective with telic predicates (Andersen, 1991, 2002), as Example

2 illustrates.

Example 2. Advanced use of the L2 French past tense

| 2.a. Il se réveillait | He wake+imperfective up | |

| 2.b. Il courrait deux kilomètres | He run+imperfective two kilometres | |

| 2.c. Il a été content | He be+perfective happy | |

| 2.d. Il est resté à la maison | He stay+perfective home |

The analyses of learner performance throughout the MI materials revealed larger error rates among the less proficient learners using Set 2 and more advanced learners using Set 1. In these conditions, the participant dropout rate during the experiment was higher. Learner answers in a questionnaire and informal interviews evaluating the suitability of the environments showed that the less proficient learners using Set 2 felt overwhelmed with the L2 level of the materials, whereas the most past-tense proficient learners using Set 1 reported interest loss in task completion, as they felt they were not learning.

II. Method

Based on these issues, this study examined the interplay between the type of

MI, L2 proficiency level and different types of L2 learner

attitudes. Specifically, the purpose of this study was to identify the effects

of two types of MI (i.e., MI with

or without LATS) among learners of French from two L2

proficiency levels (i.e., low or intermediate) on two types of L2 learner attitudes

(i.e., attitudes towards L2 learning or towards the L2 class).

Participants. A total of 76 participants, who were enrolled in five

different sections of a BA in Modern Languages, participated

in the study. In addition to French, they were learning English and Italian

as part of the BA program. The French courses focused

on the development of L2 communication, linguistic awareness, and cultural knowledge.

The teachers rarely used multimedia CD-ROMs

or presentations to cover the course topics. Most of the learners (n=70)

were between 19 and 24 years old (Mage=21, SD=2).

There were 14 male and 62 female learners. Over half of the participants (n=44)

had just begun learning French in the BA, whereas 32 had

learned French in language institutes.

Treatment Materials. Two sets of multimedia materials were developed

to teach the distinctive use of the French perfective “passé composé” and imperfective

“imparfait.” The perfective marks the completeness of events, whereas the imperfective

indicates the manner in which events unfold (i.e., habituality, continuity,

progression). These forms were selected, because their contrastive use constitutes

a documented L2 acquisition challenge. In immersion programs in Canada (Harley,

1992; Harley & Swain, 1978) and language classes in North America (Izquierdo

& Collins, 2008; Izquierdo, 2009, 2014) and Europe (Howard, 2001, 2002), learners

with high L2 proficiency levels often exhibit a preference for the use of emerging

past-tense forms (See Example 1) in contexts where the French native speakers

would prefer forms characterizing the advanced use of the past tense (See Example

2).

To expose learners to the target forms, two sets of MI

materials were designed. Set 1 operationalized MI without

Language Awareness Tasks (MI-LATS), whereas Set 2 was

designed to include MI with Language Awareness Tasks (MI+LATS).

Both sets included the same contexts (n=96) for the treatment of emergent

and advanced perfective and imperfective forms. Two silent episodes of The Pink

Panther Show were used to contextualize the use of the past tense forms. Lesson

1 and 2 built upon the Put-Put, Pink episode (Ryan, 1968),

whereas Lessons 3 and 4 dealt with the Pink Panic episode (Dunn, 1967).

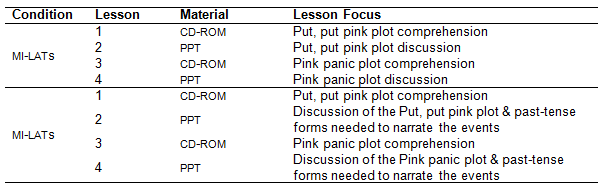

Table 1 displays MI material organization.

Table I. Experimental

MI material organization

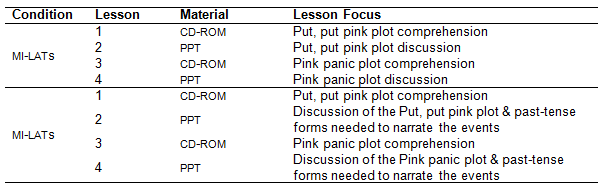

Set 1 exposed learners to the use

of the past tense through meaning-based MI via comprehension

and production tasks only. Following the design of previous MI

studies (Izquierdo, 2007, 2014), Lessons 1 and 3 were implemented through comprehension-based

tasks using a CD-ROM application,

which the participants used individually under teacher surveillance in the computer

lab during in-class time. The application required learners to identify a series

of sentences about the lesson video story as true or false. Throughout the application,

interactive annotations with definitions and pictures were provided in the lower

part of the screen for potentially unknown words. The application presented

the video-cartoon in eight segments. Prior to watching each segment, learners

read four statements about the story (Figure 1). After the segment, the four

statements were presented again. If learners were ready to answer, they moved

through a series of screens to indicate, using true or false push buttons, the

veracity of the statements. Correct answers led to a cheering statement and

feedback on the video cartoon plot. No feedback on form was provided on the

CD materials (for a discussion on the distinction between

feedback on form and meaning, see Lyster & Izquierdo, 2009). If the answer was

not correct, an incorrect selection statement and a textual and a pictorial

explanation were provided (see Izquierdo, 2014, p.200).

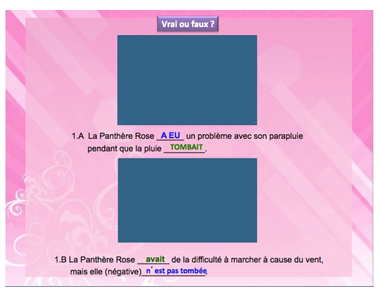

During Lessons 2 and 4, the production tasks were implemented using PowerPoint

(PPT) presentations. These lessons were teacher-fronted

and acted as classroom follow-up lessons to help learners consolidate Lessons

1 and 3. For each lesson, a PPT including 64 true/false

sentences about the story plot was used. Each sentence was presented on a PPT

slide (See Figure 1). After reading two sentences, learners worked in triads

to discuss the sentence veracity. Then, triads discussed their answer with the

class. Finally, the teacher clicked on the PPT presentation

to show the target sentences and pictures from the cartoon to confirm or dismiss

the class answers. In order to help learners visually perceive the target forms,

the verbs with the perfective were highlighted in blue and the verbs in imperfective

were in green.

Figure 1. True/false sentence PPT slide in MI-LATs

(images excluded due to Copyright)

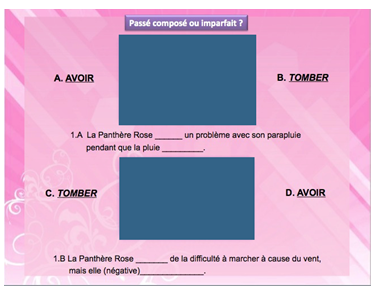

Set 2 exposed learners to meaning-based

MI with LATs.

Following the design of L2 studies including LATs that

led to significant L2 learning effects in regular classroom contexts (see Lyster,

2004), this MI type included tasks providing learners

with opportunities to discuss the form-meaning relationship of the past tense

in sentences embedded in meaning-oriented contexts.

The comprehension-based tasks from Lessons 1 and 3 in Set 1 were retained in

Set 2 to present identical meaning-oriented contexts across the experimental

sets. Nevertheless, the production tasks in Lessons 2 and 4 from Set 1 were

slightly modified for Set 2 to help learners reflect upon the use of L2 past-tense

forms in the true/false meaning-oriented sentences. In the PPT

sentences, the verbs were removed and presented on the slide margin. In addition,

an image from the video cartoon was presented to illustrate the event referred

to in the sentence. After the teacher presented two sentences, the learners,

again in triads, agreed on the verb missing in the sentence and the past marker

rendering the story event referred to in the video-cartoon image. Then, the

learners discussed their verb and past tense choice. After the discussion, the

teacher clicked on the PPT to complete the sentence and

checked the class’ answer.

Figure 2. True/false sentence PPT slide in MI-LATs

(images excluded due to Copyright)

During a three-hour workshop, the

researchers presented the project and the materials to the participating lecturers,

who agreed to implement one of the MI sets in their classes,

as their syllabi required them to review the past tense forms. The lecturers

selected their corresponding MI set in line with their

teaching preference. Set 1 was implemented in three French sections, whereas

Set 2 was implemented in two sections. Each set included an implementation manual.

In order not to bias the project results, the lecturers agreed to cover the

French past using the MI set only.

Proficiency test.

Following the methodology of L2 developmental studies (see Bardovi-Harlig, 2000;

Collins, 2002), a past-tense knowledge test was designed to group learners into

the two proficiency levels.2

It included 20 written passages with short dialogues and narratives. In the

passages, the verbs were removed from the sentences and provided in parentheses.

Based on each passage story plot, learners inflected the verbs for present,

past or future, as the excerpt below illustrates.

Excerpt from the proficiency test (Situation12)

A: Hein ! J’ai entendu dire que ton père a gagné le loto.

B: Oui. Durant le week-end, je (visionner) ___________ mon film favorite quand

ma sœur m’a téléphoné pour m’annoncer la nouvelle.

Excerpt translation

A: Hey, I heard your dad won the lottery!

B: Yes. Last weekend, I (watch) _________my favourite ?lm when my sister rang

me up to share the news.

The test included 50 obligatory contexts for the use of the perfective and imperfective

and 18 distractors eliciting present (n=9) and future (n=9)

forms. The use of the target L2 forms across the 74 verbs was piloted with nine

university-educated Francophones (aged 28-50 years). To avoid high scores resulting

from biased production of emergent past-tense forms only, the 50 past-tense

items included a balanced number of contexts (25 for each) for the emergent

and advanced use of the perfective and imperfective (for details, see Izquierdo

& Collins, 2008).

The learners received one point for each correct answer for both the perfective

and imperfective items. Thus, their scores could range from 0 to 50. Using the

Francophones’ answers, two research assistants scored each test independently.

The comparisons between the research assistants' scores yielded a disagreement

rate of 39% (30/76). Yet, an inter-rater reliability check for the overall test

score agreement of the two research assistants yielded a high Pearson correlation

coefficient, r=.996, ρ<.001. Nevertheless, the assistants

scored the problematic tests again and reached a consensus.

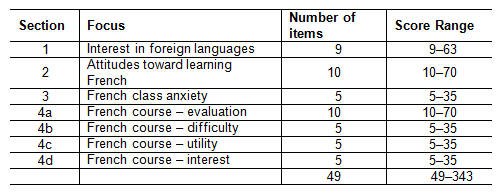

Attitude/Motivation Test Battery (AMTB). To examine

the learner attitudes toward the L2 class and L2 learning, Gardner's (1985b)

revised version of the AMTB was chosen, as its items were

designed for L2 learners of French and were validated in various international

contexts. The AMTB was developed for English-speaking

Canadian learners of French. Thus, some sections elicited opinions toward French

Canadians, interest in integrating in French-speaking Canada and the utilitarian

value of French in Canada. Due to this issue, only the seven AMTB

sections presented in Table 2 were retained3

as they related to the learner attitudes of interest for the study. The test

was translated to Spanish and piloted with learners of French at the participating

university's language center. The piloting revealed no problems with the Spanish

version.

Table II. AMTB

sections retained for the study

Section Focus Number of items Score

Range 1 Interest in foreign languages 9 9–63 2 Attitudes toward learning French

10 10–70 3 French class anxiety 5 5–35 4a French course – evaluation 10 10–70

4b French course – difficulty 5 5–35 4c French course – utility 5 5–35 4d French

course – interest 5 5–35 49 49–343 From Sections 1 to 3, answers related to

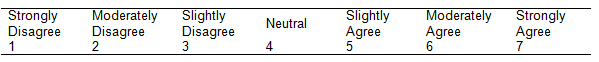

agreement reactions with a statement (Example 3). The items in the remaining

sections elicited the learners' evaluative reactions toward the French class

(Example 4; the scores underneath the scale choices were omitted in the test).

For all items, the scores ranged from one to seven depending on how positive

the expressed opinion was. Two counter-balanced versions of the AMTB

were used. The same items were presented in reverse order. During the pre-test,

half the learners answered version A and the other half answered version B.

During the post-test, the test versions were alternated.

Example 3. Section 2, Item 1 (Gardner, 1985b, pp. 17-18)

Circle the alternative below the statement which best indicates your feeling.

If I were visiting a foreign country, I would like to be able to speak the language

of the people.

Example 4. Section 16, Item

1 (Gardner, 1985b, pp. 23, 25)

Place a checkmark in the scale below to rate your French course.

1. My French course is

![]()

The learners received one score

for each of the seven AMTB sections retained for the study,

as the value given through the evaluation reactions were added up by section.

For each testing occasion, seven scores were computed per learner. In total,

1064 scores were included in the statistical analyses. Two research assistants

scored each test independently. Although the comparisons between the research

assistants’ scores yielded a disagreement rate of 1% (11/1064), an inter-rater

reliability check for overall agreement on the answer codifications revealed

a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 1. The assistants computed the problematic

scores again to reach a consensus.

Experimental Conditions. Within their French sections, participants were

classified into one of two past-tense proficiency levels based on the results

of the past-tense test. In the test, the scores ranged from 1 to 44 points.

To create two equal score ranges, the split point was set at 22. Participants

with a score between one and 22 points were classified at a low past-tense proficiency

level (n=34, M=16.65, SD=3.76).

Participants who scored over 22 points were classified at an intermediate past-tense

proficiency level (n=42, M=31.17, SD=6.70). The

combination of the learner past-tense proficiency and the MI

implemented in the French sections led to four experimental conditions: learners

with low past-tense proficiency exposed to MI+LATS (n=17,

M=16.35, SD=3.67) and MI-LATS

(n=17, M=16.94, SD=3.93); and

learners with intermediate past-tense proficiency exposed to MI+LATS

(n=14, M= 29.79, SD=6.29) and

MI-LATS (n=28, M=31.86,

SD=6.91).

Two-way ANOVAs were conducted to identify significant

effects for L2 past-tense knowledge and type of MI across

conditions. With α=.05, the results yielded a significant effect for past-tense

proficiency only, F(1,72)=113.67, ρ<.001, with a large

Cohen's effect size, d=2.78, and thus, confirmed that learners classified

at an intermediate level had more control over past-tense forms than their less

proficient counterparts.

III. Analyses & Results

Statistical Analyses Procedures. To

identify significant effects between and within the experimental conditions,

the data from each AMTB section were analysed independently

using three types of non-parametric analyses. Non-parametric tests were selected

due to the ordinal nature of the AMTB rating scales (Romano,

Kromrey, Coraggio & Skowronek, 2006). The Wilcoxon test was used to identify

attitudinal changes within each experimental condition, as the data were elicited

from the same learners but at two different testing times (see Fields, 2005).

To examine attitudinal differences between the four experimental conditions,

the Kruskal-Wallis test was used, as the data came from more than two groups

during the same testing time (Fields, 2005). Effects were significant when their

p was smaller than α=.05.

When the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a significant effect, two post-hoc

pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Mann-Whitney test. One comparison

was made between the learners with low past-tense proficiency exposed to MI+LATS

and MI-LATS. The second comparison was made between learners

with intermediate past-tense proficiency exposed to MI+LATS

and MI-LATS. The Mann-Whitney test

was selected, as the data came from two experimental conditions during the same

testing time (Fields, 2005). To avoid the Type I error during the post-hoc comparisons,

the α was adjusted to .025 using the Bonferroni method (Fields,

2005). This alpha resulted from dividing .05 by the number of post-hoc

comparisons.

For significant group differences, the effect size estimate, r, was

computed by dividing the z-score test statistic provided by the statistical

software, SPSS v.18, for the group comparison by the square

root of the total number of participants involved in the group comparison. An

r below .3 represented a small effect size; an r between .3

and .5 indicated a medium effect size; finally, an r above .5 indicated

a large effect size (Fields, 2005).

AMTB version score differences. Prior to analyzing the

effects of the MI experimental conditions on the attitudinal

scores, Mann-Whitney analyses were conducted on the global AMTB

scores to identify differences between AMTB versions at

each testing time. The analyses yielded no significant differences between version

A (n=40, Mdn=283) and version B (n=36, Mdn=273) during the pre-test,

U=569, ρ=.116. Neither did the analyses reveal a significant

difference between version A (n=37, Mdn=278) and B (n=39,

Mdn=275) during the post-test, U=713, ρ=.930.

Thus, the versions were pooled.

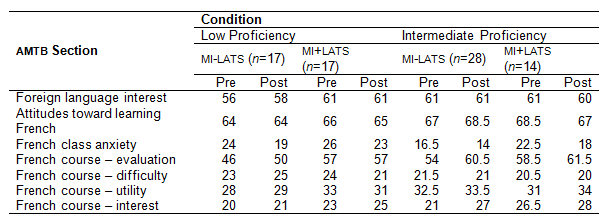

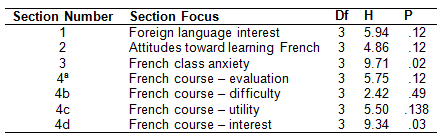

AMTB score differences between experimental

conditions during the pre-test. Across the four experimental groups, the

Kruskal-Willis test results in Table 3 indicated similar levels of interest

in foreign languages, attitudes toward learning French, French course evaluation,

French course difficulty, and French course utility in the pre-test. The pre-test

score analyses pointed to between-groups differences only with respect to learners’

anxiety and interest in the class. Yet, the post-hoc comparisons presented

in Table 4 did not reveal significant differences between MI-LATS

and MI+LATS within each past-tense condition. In terms

of learner anxiety, the post-hoc comparisons revealed similar anxiety

levels between learners at early stages of past-tense marking exposed to MI+LATS

and MI-LATS (U=107, p=.195) and between learners

at late stages of past-tense marking exposed to MI+LATS

and MI-LATS, (U =123.5, ρ=.05).

In terms of course interest, the post-hoc comparisons did not reveal

significant differences between learners at early stages of past-tense marking

exposed to MI+LATS and MI-LATS (U=96,

p=.09) or between learners at late stages of past-tense marking exposed to MI+LATS

and MI-LATS, (U=122.5, p=.04).

Table 3. AMTB

result medians for experimental conditions

Table 4. Kruskal-Willis

test results for AMTB pre-test score differences between

groups

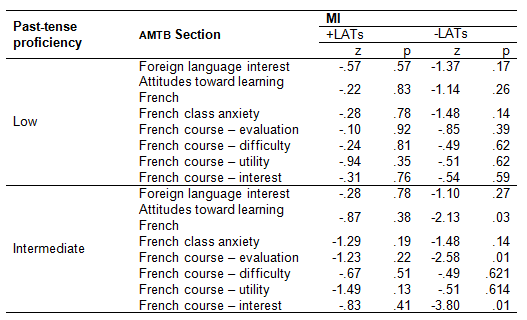

Table 5. Wilcoxon

Analyses for Significant Differences between Testing Times

AMTB score changes within experimental conditions. The Wilcoxon results, presented in Table 5, revealed that neither type of MI led to attitude changes among low-proficient learners from pre-test to post test. Yet, within the more proficient learners, the analyses revealed the evolution of different attitudes depending on MI condition (see Table 3). MI+LATS did not alter any of the learner attitudes between the pre and post-tests. However, MI-LATS led to positive changes with respect to attitudes toward learning French, ρ=.03, r=.39, French course evaluation, ρ=.01, r=.49, and French course interest, ρ=.01, r=.72.

IV. Discussion

The attitudes teachers and students

hold toward technology can intervene in the successful integration of computers

in educational practices (Bax, 2003; O’Connor & Gatton, 2003). To expand our

understanding of the variables influencing L2 learner attitudes, this study

examined the relationship between the type of MI, the

L2 learner proficiency profile, and various L2 learner attitude types.

Our results suggest that LATS were well received among

the participants in MI, since their use did not alter

the various attitude types examined among the learners with different past-tense

proficiency levels. The meaning-based MI condition (i.e.,

MI-LATS), however, prompted positive changes among the

most past-tense proficient learners with respect to their attitudes toward learning

French, their French course evaluation, and their French course interest. These

findings suggest that the MI type can interact with the

L2 proficiency of learners affecting different learner attitude types.

These findings are congruent with previous research showing that the MI

experience can foster positive L2 learner attitudes toward the instructional

materials (e.g., Ayres, 2002; Leakey & Ranchoux, 2006; Sagarra & Zapata, 2008).

These results lend support to the need for a differentiation in the attitude

types that intervene during computer instruction (e.g., Mahfouz & Ihmeideh,

2009; VanAacken, 1999). They provide support for the arguments that CALL

research should explore the manner in which variations in the learner profile

and the instructional approach within a computerized learning context influence

L2 learner results (Chapelle, 2004; Izquierdo, 2014; Reeder et al, 2004).

While MI positively influenced learners' attitudes toward

the L2 class, learner attitudes towards the process of L2 learning remained

stable within the meaning-based group during the experiment. Gardner (1985a)

and his associates argued that learner attitudes toward the instructional context

could vary depending on the learners’ likes and dislikes of teaching strategies

and the teacher. Learner attitudes toward L2 learning, however, are deeply rooted

in the willingness, desire and efforts of learners to learn a new language.

Due to this difference, it might then be possible that MI

could lead to a gradual development of L2 learner attitudes, where MI

would, first, influence classroom-related attitudes and, then, attitudes toward

L2 learning. Given the classroom nature of the experiment, the participating

teachers' syllabus compliance with time played a determinant role in the length

of the MI administered. Thus, future research could address

the impact of MI delivered over longer periods of times

and sustained instructional approaches on the gradual development of the various

types of L2 learner attitudes in classrooms.

The learner attitude responses to MI-LATS were partially

congruent with two assumptions behind the study. Building upon Krashen's (1992,

1994) argument that overt instruction on the L2 increases anxiety, learner attitudes

were expected to negatively respond to MI+LATS. Yet, the

statistical results were not in line with this expectation. The second assumption

was that the absence of LATS in MI

would foster a large range of attitudinal changes. Nonetheless, as previously

discussed, changes were only observed with respect to learner attitudes towards

the classroom context. These reactions towards LATS could

relate to the prior instruction experience of the participants. In their L2

program, learners usually complete tasks that overtly draw their attention to

L2 communicative competence and linguistic awareness. This learning experience

resembled the L2 instructional approach of MI+LATS.

Thus, for these participants, MI+LATS

represented a change in the instructional modality, since teachers rarely used

multimedia, but did not involve an instructional approach change. MI-LATS,

however, implied a higher degree of instructional novelty due to a change in

the instructional approach, as the learners fully experienced meaning-based

instruction with respect to grammar learning, and in a new instructional modality,

as the L2 exposure occurred through multimedia. Indeed, studies conducted in

various instructional contexts indicate that a change in the instructional approach

and modality could lead to divergent attitudes among L2 learners (e.g., Leakey

& Ranchoux, 2006; Loucky, 2005; Sagarra & Zapata, 2008). However, research is

needed to determine the extent to which the novelty effect can foster long-term

L2 learning benefits (Chapelle, 2001). The attitude changes that MI-LATS

fostered among the most proficient past-tense learners provide empirical support

for our argument that the stage of L2 grammar development at which learners

receive a certain type of MI could have an impact on their

attitudes (De la Cruz & Izquierdo, 2014; Izquierdo, 2007, 2014). Unlike our

previous studies (Izquierdo, 2007, 2014), in the current study, learners from

both L2 past-tense knowledge proficiency levels were exposed to the same level

of L2 complexity, as the multimedia materials included an equal number of emergent

and advanced developmental forms. Nevertheless, while this exposure might have

provided learners in both proficiency conditions with an appropriate L2 learning

challenge level, the MI type whereby the target forms

were delivered interacted with the L2 learner profile. During the classroom-based

tasks, learners needed to interact with their peers in the L2. Among learners

in the MI+LATS, one difficulty might

have related to the language and terminology required to explain their past-tense

choices. Indeed, L2 acquisition research has provided evidence that the language

required to talk about the language can intervene with task completion (García-Mayo,

2007). The least proficient learners using MI-LATS

also needed the L2 to justify the veracity of the true-false statements and,

to do so these learners might have needed lexical and grammatical forms beyond

their L2 capabilities.

V. Conclusion

Our results suggest that attitudinal changes could occur once the learners have attained a late stage of L2 grammar proficiency. Nevertheless, their acquaintance with LATS through their regular classroom-learning experience could have influenced the results. MI+LATS mostly represented an instructional modality change (i.e., multimedia). Yet, MI-LATS involved a change in both instruction type and modality. The most proficient learners could have found extensive opportunities to practice the L2 forms that they were ready for in the meaning-oriented nature of MI-LATS, outside their regular classroom learning conditions. These results point to the importance of varying the instructional materials and tasks as learner proficiency and learning experience evolve. Moreover, they suggest that changes towards classroom-related attitudes prompted through instructional modality might not necessarily foster changes in attitudes intrinsically rooted in the willingness, desire and efforts to learn a new language.

Referencias

Andersen, R. W. (1991). Developmental

sequences: The emergence of aspect marking in second language acquisition. In

C. A. Ferguson & T. Huebner (Eds.), Crosscurrents in second language acquisition

and linguistic theories (pp. 305-324). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Andersen, R. W. (2002). The dimensions

of pastness. In R. Salaberry & Y. Shirai (Eds.), The L2 acquisition of tense-aspect

morphology (pp. 79-105). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ayres, R. (2002). Learner attitudes

towards the use of CALL. Computer Assisted Language Learning,

15, 241-249. Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2000). Tense and aspect in second language

acquisition: Form, meaning, and use. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bax, S. (2003). CALL -past, present and future. System,

31, 13-28 Chapelle, C. (1998). Multimedia CALL:

Lessons to be learned from research on instructed SLA.

Language Learning and Technology, 2, 22-34.

Chapelle, C. (2001). Computer applications in second language acquisition. New

York: Cambridge University Press. Chapelle, C. (2004). Technology and second

language learning: Expanding methods and agendas. System, 32,

593-601.

Collins, L. (2002). The role of L1 influence and lexical aspect in the acquisition

of temporal morphology. Language Learning, 52, 43-94.

De la Cruz, V., & Izquierdo, J. (2014). Multimedia Instruction on Latin Roots

of the English Language and L2 Vocabulary Learning in Higher Education Contexts:

Learner Proficiency Effects. Sinéctica, Revista Electrónica de

Educación, 42, 1-11.

Dunn, J. W. (Writer) (1967). Pink Panic, The Pink Panther Show. U.S.A.:

United Artists. Ellis, R. (2001). Investigating form-focussed instruction. Language

Learning, 51, 1-46.

Felix, U. (2008). The unreasonable effectiveness of CALL:

What have we learned in two decades of research? ReCALL,

20, 141-161. Fields, A. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS.

London, UK: SAGE.

García-Mayo, M. P. (Ed.) (2007). Investigating tasks in formal language

learning. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Gardner, R. (1985a). Social psychology and language learning: The role of

attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. (1985b). The Attitude/Motivation Test Battery: Technical Report.

London, ON: University of Western Ontario.

Gardner, R., Lalonde, R., & Moorcroft, R. (1985). The role of attitudes and

motivation in second language learning: Correlational and experimental correlations.

Language Learning, 35, 207-227.

Gardner, R., & MacIntyre, P. (1985). An instrumental motivation study in

language study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13, 57-72.

Gardner, R., Tremblay, P., & Masgoret, A. (1997). Towards a full model of second

language learning: An empirical investigation. The Modern Language Journal,

81, 344-362.

Harley, B. (1992). Patterns of second language in French immersion. French

Language Studies, 2, 35-79. Harley, B., & Swain, M. (1978). An

analysis of the verb system used by young learners of French. Interlanguage

Studies Bulleting, 3, 35-79.

Howard, M. (2001). The effects of study abroad on the L2 learner's structural

skills. EUROSLA Yearbook, 1, 123-141.

Howard, M. (2002). Prototypical and non-prototypical marking in the advanced

learner's aspectuo-temporal system. EUROSLA

Yearbook, 2, 87-113.

Izquierdo, J. (2014). Multimedia instruction in foreign language classrooms:

Effects on the acquisition of the French perfective and imperfective distinction.

The Canadian Modern Language Review, 70 (2), 188-219.

Izquierdo, J. (2009). L’aspect lexical et la production des temps du passé en

français L2 : une étude quantitative auprès d’apprenants hispanophones –

La revue canadienne de langues vivantes, 65, 587-613.

Izquierdo, J., & Collins, L. (2008). The facilitative effects of L1 influence

on L2 tense-aspect marking: Hispanophones and Anglophones learning French.The

Modern Language Journal, 93, 350 -368.

Izquierdo, J. (2007). Multimedia instruction in foreign language classrooms:

Effects on the acquisition of the French perfective and imperfective distinction.

PhD dissertation, McGill University, Canada.

Kawauchi, C. (2005). Proficiency Differences in CALL

Based Vocabulary Learning: The Effectiveness of Using “PowerWords” FLEAT

5, 55-65.

Krashen, S. (1992). Teaching issues: Formal grammar instruction. TESOL

Quarterly, 26, 409-411.

Krashen, S. (1994). The input hypothesis and its rivals. In N. Ellis (Ed.),

Implicit and explicit learning of languages (pp. 45-77). London: Academic

Press.

Leakey, J., & Ranchoux, A. (2006). BLINGUA. A blended

language learning approach for CALL. Computer assisted

language learning, 19, 357-372.

Loucky, J. P. (2005). Combining the benefits of electronic and online dictionaries

with CALL Web sites to produce effective and enjoyable

vocabulary and language learning lessons. Computer Assisted Language Learning,18,

389 – 416.

Lyster, R., & Izquierdo, J. (2009). Prompts versus recasts in dyadic interaction.

Language Learning, 59, 453-498.

Lyster, R. (2004). Research on form-focused instruction in immersion classrooms:

implications for theory and practice. Journal of French Language Studies,

14, 321-341.

Masgoret, A., & Gardner, R. (2003). Attitudes, motivation and second language

learning: A meta-analysis of studies conducted by Gardner and associates. Language

Learning, 53, 123-163.

Mahfouz, S. & Ihmeideh, F. (2009). Attitudes of Jordanian university students

toward using online chat discourse with native speakers of English for improving

their language proficiency. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22,

207 - 227.

Morales, D. & Izquierdo, J. (2011). L2 Phonology Learning among Young-Adult

Learners of English: Effects of Regular Classroom-based Instruction and L2 Proficiency.

Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 13, 1, 1-22.

O'Connor, P. & Gatton, W. (2003). Implementing multimedia in a university EFL

program: A case study in CALL. In S. Fotos and C. Browne

(Eds). New perspectives on CALL for second language

classroooms (pp. 199-224). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Plass, J. L., & Jones, L. C. (2005). Multimedia learning in second language

acquisition. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia

learning (pp. 467-488). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Reeder, K., Heift, T., Roch, J., Tabyanian, S., & Gölz, P. (2004). Toward a

E/Valuation for Second Language Learning Media. In S. Fotos and C. Browne (Eds).

New perspectives on CALL for second language classroooms

(pp.255 -278). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Romano, J., Kromrey, J., Coraggio, J., and Skowronek, J. (2006). Appropriate

statistics for ordinal level data: Should we really be using t-test and Cohen's

d for evaluating group differences on the NSSE and other

surveys? Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Florida Association

of Institutional Research, Cocoa Beach, Florida. Ryan, J. (Writer) (1968). Put-Put,

Pink, The Pink Panther Show. U.S.A.: DePatie-Freleng Enterprises.

Sagarra, N., & Zapata, G. (2008). Blending classroom instruction with online

homework: a study of student perceptions of computer-assisted L2 learning. ReCALL,

20, 208-244.

Sanz, C. (2004). Computer-delivered implicit versus explicit feedback in processing

instruction. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction (pp. 227-240).

Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Sanz, C., & Morgan-Short, K. (2004). Positive evidence versus explicit rule

presentation and explicit negative feedback: A computer-assisted study.

Language Learning, 54, 35-78.

Simard, D., & Wong, W. (2004). Language awareness and its multiple possibilities

for the L2 classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 37, 96-110.

Spada, N., & Tomita, Y. (2010). Interactions between type of instruction and

type of language feature: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 60,

263-308.

VanAacken, S. (1999). What motivates L2 learners in the acquisition of Kanji

using CALL: A case study. Computer Assisted Language

Learning, 12, 113-136.

1We

acknowledge the contribution of our participants and research assistants throughout

the study. We are grateful to Stephen MacDonald for his feedback on previous

versions of the manuscript. Funding for this project was obtained by the first

author through an Institutional Research Grant (PFICA

2008, POA 20090368). Preliminary results of the study

were presented at the 2011 Congress of the Computer Assisted Language Learning

Consortium. University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada.

2Further

information on the development and use of the test to determine the L2 past-tense

stage of learners of French can be found in Izquierdo and Collins (2008).

3Item

2 from Section 2 was excluded, as it related to the Canadian context.

Cómo citar: izquierdo, J., Simard, D. y Garza, M. G. (2015). Multimedia instruction

& language learning attitudes: a study with university students. Revista Electrónica

de Investigación Educativa, 17(2), 101-115. Retrieved from http://redie.uabc.mx/vol17no2/contents-izqsimard.html