Revista Electrónica de Investigación

Educativa

Vol. 16, Núm. 2, 2014

Representations of Academic

Life:

Institutional and Personal Values

Flavia Vieira (*)

flaviav@ie.uminho.pt

José Carlos Morgado (*)

jmorgado@ie.uminho.pt

Judite Almeida (*)

juditealmeida@bio.uminho.pt

Manuela Silva (*)

nini@quimica.uminho.pt

Joaquim Sá (*)

jgsa@ie.uminho.pt

(*) Universidade do Minho

Campus de Gualtar

Braga, Portugal

(Recibido: 9 de junio de 2013; Aceptado para su publicación: 5 de marzo de 2014)

Abstract

The way academics construct professional identities and operate in a complex

profession that is under pressure depends on how they position themselves in

relation to institutional cultures. In order to investigate faculty representations

of academic life, a survey case study (questionnaire and interviews) focusing

on potential dissonance between institutional and personal values was conducted

at the University of Minho (Braga-Portugal), a research-teaching university.

Dissonance was found related to teaching, research, working climate, relationships

and leadership, suggesting a person-organization misfit. Dissatisfaction arising

from values incongruence co-exists with efforts for self-fulfilment as academics

struggle to preserve their identity while realizing that institutional priorities

may run counter to their ideals. Acknowledging dissonance as a vital element

within a culture of respect for diversity would foster the negotiation of understandings

about what the academic community is and might be. Institution-specific inquiry

into academic experience should not only be expanded but also become part of

the strategic (re)definition of institutional development policies.

Keywords: Representations, Academic life, Values, Dissonance.

I. The need to inquire into academic life on campus

Extraordinarily, universities, while claiming to be in the business of knowledge,

know very little about themselves (Barnett, 1997, p. 17).

What Barnett suggested long ago still holds true in many settings. And even

though knowledge about the higher education landscape has increased immensely,

we still know too little about our own institutions. Yet, how can the quality

of academic life on campus be improved without inquiring into it? As Johnsrud

(2002, p. 393) argues, “colleges and universities pay a price for ignoring

the quality of worklife experienced by members of their faculty and administrative

staff. (…) The vitality and quality of the entire academic enterprise

depends on their performance”.

Inquiry into institution-specific academic experience is particularly urgent

given the crisis in the hegemony and legitimacy of the 20th century university

and the changing face of the profession, namely as regards the implications

of globalization and managerialism upon the redefinition of higher education

purposes, policies, and academic roles and identities (see Altbach et al.,

2009; Barnett, 1997; Coaldrake and Stedman, 1999; Courtney, 2013; Fredman and

Doughney, 2012; Henkel, 2007; Morley, 2003; Meek et al., 2009; Santos,

2008). Even though current conditions may stimulate professional growth and

satisfaction (Locke and Bennion, 2010), experts’ views at the UNESCO

Forum for Higher Education, Research and Knowledge 2001-2009 indicate that “the

notion of a ‘profession under pressure’ is more often presented

than one of improving quality and relevance and than one of an increasingly

satisfying professional situation” (Teichler and Yagci, 2009, p. 107).

The way academics build professional identities and operate in a complex profession

under pressure depends on how they position themselves in relation to institutional

cultures, here defined as dominant patterns of espoused values considered to

be valid on the basis of shared experience and problem-solving (Schein, 2010).

Organizational cohesion and growth are enhanced when culture has a holographic

quality through the representation and enactment of shared systems of meanings

(Morgan, 2006). However, higher education institutions are sites where competing

rationalities create a struggle of opposites, reflecting the fact that “any

system development always contains elements of counterdevelopment” (p.

282). Conflicting work ideologies provoke fractures in academic identity especially

when personal autonomy is threatened by measures that reinforce internal quality

control towards collective action and institutional autonomy (Henkel, 2007;

Waitere et al., 2011; Winter, 2009). Moreover, when managers create

survival anxiety or guilt for resisting dominant discourses and practices, they

may generate learning anxiety, denial, scapegoating, maneuvering and bargaining

(Schein, 2010). Institutions may even become unsafe places where incivility,

alienation and occupational stress seriously affect academics’ well-being

and productivity (Ditton, 2009; Morley, 2003; Twale and De Luca, 2008).

Enhancing faculty engagement requires investing in the intellectual capital

of institutions and cultivating a culture of respect for diversity (Gapa, Austin

and Trice, 2007). Therefore, we need to know more about academics’ views

of worklife and inquire into dissonance between perceived dominant values and

personal values. This was the main purpose of the exploratory case study here

reported. Even though it focuses on one institution and only touches the surface

of a complex phenomenon, it may resonate in similar settings and contribute

to an increase in debate on dissonance as a vital element of inclusive academic

life, allowing us to get a grasp on “repressed forces lurking in the shadow

of rationality” (Morgan, 2006, p. 237).

When dissonance is dismissed or silenced, issues that affect us deeply as professionals

tend to become naturalized and culturally accepted. On the contrary, when it

is voiced and acknowledged, a space is created for liberation, dialogue and

transformation. From this perspective, research that seeks to disclose, interrogate

and reframe understandings of institutions can be empowering. It entails “a

return to the beginning: What sort of community is desired?” (Schostak

and Schostak 2008, p. 250). To a certain extent, our study seeks provisional

answers to this unsettling question.

II. Inquiring into views of academic life: A survey case study

2.1 Research context and objetives

The survey case study here reported was conducted in 2009/2010 at our university.

The University of Minho (Braga-Portugal) is a teaching-research institution

founded in 1973 that offers a wide range of undergraduate and graduate programs

involving around 1,200 faculty and 18,000 students within eleven colleges. Like

other institutions across the country, it has struggled to keep up with escalating

quality demands deriving from transnational, managerial trends and policies

in a context of national economic crisis. There appears to be a growing divide

between “academic managers” and “managed academics”

as regards academic values (Winter, 2009), reinforced by a mismatch between

quality demands (related to expanded roles and professionalism, fund raising,

internationalization, accountability, excellence, and collective commitment

to institutional development) and the deterioration of working conditions resulting

from funding cuts, growing job insecurity, reduced autonomy and opportunities

for promotion, increased workload and bureaucracy, and lack of support structures

for change (see Santiago and Carvalho 2008, 2012).

In this scenario, our study proposed to: (1) compare perceived institutional

values with personal/ideal values in diverse domains of academic life; (2) gain

insight into the impact of values incongruence on the way academics perceive

and (re)shape professional experience; (3) identify the conditions necessary

for a culture of greater respect for diversity.

To our knowledge, no study of this kind had been conducted before in the country,

where research on academic work is an emergent field and has focused primarily

on management issues. We found ourselves entering a sensitive terrain that involved

self-exposure and an inquiry stance towards the institutional culture, and this

determined some of our decisions regarding methodological procedures.

2.2 Research procedures and participants

An anonymous survey questionnaire was designed and reviewed by three colleagues

from other universities and a foreign expert (Ronald Barnett). The final version

integrates 20 closed questions focusing on various facets of five domains of

academic life: academic activities; assessment of teaching and research; career

promotion; leadership; working climate and relationships (see sample questions

in

Appendix 1). Respondents were asked to express their opinion about a) what

is valued (important or present) in the institution (perceived institutional

values), and b) what should be valued (personal/ideal values). They also expressed

average (dis)satisfaction regarding the five domains on a 9-point scale (-4=Completely

Dissatisfied; 0=Neutral Position; +4=Completely Satisfied). This scale was later

converted to a 1-9 scale in order to calculate mean and standard deviation values.

Personal data collected was minimal in order to protect identity (college, academic

position, length of experience in higher education, age range, and gender).

The questionnaire and a project summary were first posted to the Rectorship

Office, the Quality Assurance Office, college directors, and heads of departments

so as to inform the administrative staff about the study. Shortly thereafter,

the questionnaire, a project summary and a return envelope were posted to all

faculty (n=1153). For a period of about one month, regular e-emails were sent

across campus to ask and thank for collaboration.

The response rate was 25.1% (n=290), which means that this study is exploratory

and caution needs to be taken regarding the significance of results. The sample

distribution across colleges/disciplinary fields and academic positions matches

roughly the distribution on campus. It is also heterogeneous as regards type

of appointment (equitative distribution of non tenure-track and tenure-track

faculty), gender (equitative distribution of male and female respondents), and

length of experience in higher education (from 1-5 to +20 years).

Although we might expect a higher response rate in a study on worklife experience,

we need to consider the sensitive and marginal nature of the study and the fact

that the survey was not launched by the Quality Assurance Office. Asking it

to sponsor the study would probably guarantee a higher response rate, and this

possibility was considered, but it might also reduce our research autonomy and

generate a need for compliance on the part of respondents.

A descriptive statistical analysis of the survey data was done and two open

seminars were organized on campus to discuss results with participants and invite

them to volunteer for a semi-structured interview aimed at collecting personal

accounts. This procedure was based on the assumption that seminar attendants

would be interested in the study and thus more willing to be interviewed. Around

30 colleagues attended the seminars and 9 colleagues from 4 different colleges

later contacted the team coordinator to be interviewed. Given the short number

of interviews, they were used to get some insights into and illustrate the way

academics experience life on campus.

The interview protocol integrated 18 open-ended questions about three topics:

management of academic activities, institutional climate, and the importance

of academic life issues (see sample questions in Appendix

2). The protocol was sent to the interviewees in advance so that they could

get acquainted with it and feel more comfortable about participating. The interviews

were conducted and tape-recorded by the coordinator, and later transcribed by

team members in order to ensure maximum confidentiality. The transcriptions

were sent to the interviewees for content validation.

The fact that the study went against the grain seems to be confirmed by the

rather low participation rate and also the absence of feedback on the final

internal report, which was e-mailed to all faculty, the Rectorship Office, and

the Quality Assurance Office. It is our assumption that in settings where academic

life is seldom discussed, this kind of research tends to be undervalued and

needs to be expanded so as to disclose what would otherwise remain concealed,

helping institutions better appreciate and cater to diversity.

III. Results: Dissonance between perceived and ideal values

This section is organized into two themes: teaching and research; working climate,

relationships, and leadership. We will focus on dissonance between perceived

institutional values and personal/ideal values, which suggests a person-organization

mismatch resulting from values incongruence (Winter, 2009). Interview accounts

will be used to expand and illustrate some of the issues raised.

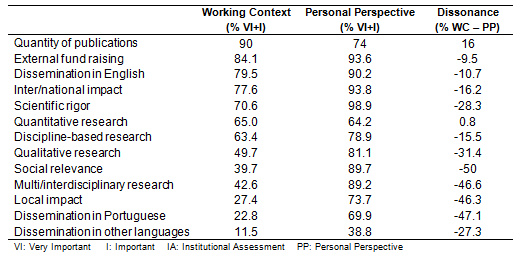

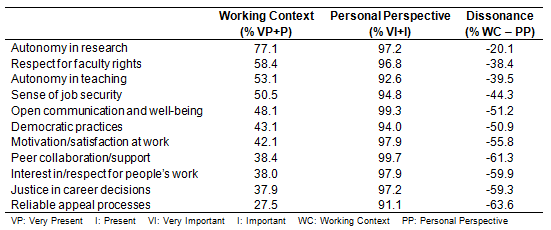

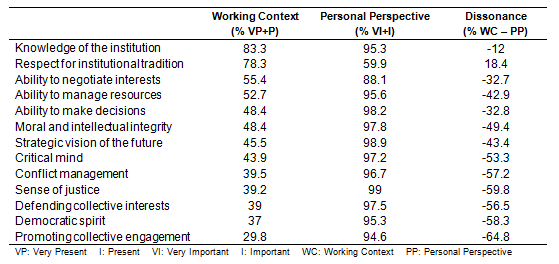

In the tables below, the percentages refer to the frequency of responses. Percentages

related to perceived institutional values are always in decreasing order. For

both institutional and personal values, we include higher ratings (Very Important

+ Important or Very Present + Present). Dissonance or incongruity for each item

is represented by the subtraction between the percentage related to perceived

culture and the percentage related to personal perspective. The minus symbol

signals a negative dissonance, i.e., the percentage of respondents who value

a given item is higher than the percentage of those who perceive it to be valued

in the institution. Average satisfaction levels refer to mean values on a scale

from 1 to 9 (from completely dissatisfied to completely satisfied). Standard

deviation values (SD) are also provided on the basis of

the same scale.

3.1 Teaching and research: what is (not) valued

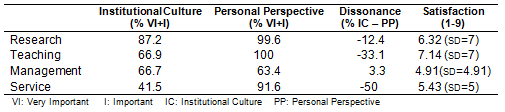

Respondents put a high value on teaching, research and service, even though

dissonance with perceived institutional values can be found in the cases of

teaching and service (Table I). Average satisfaction levels are higher for teaching

and research, but standard deviation values (SD=7) show

that there is a lot of variation in this regard. Average satisfaction with the

conciliation of the four activities is not high (5.14/ SD=2.06).

Table I. Areas of academic work

The most significant insight from the interviews as regards the management

of academic work is that even though teaching and research are both highly valued,

investment in teaching means time lost for research, and only research is perceived

to give legitimacy to one’s career as an academic (see Gottlieb and Keith,

1997; Maison and Schapper, 2012).

On the other hand, teaching itself presents problems. The interviewees stress

the deprofessionalizing effects of excessive workloads, increased bureaucracy

and accountability, and also of having to teach subjects outside their areas

of expertise due to the growing diversity of teaching programs, which is seen

as a hindrance not only to good teaching (see McInnis 2010) but also to research

and its articulation with teaching. Attempts to innovate do exist and seem to

depend more on faculty values and experience than on top-down demands. In fact,

recent reforms emphasizing the need to increase learner-centeredness tend to

be seen as rethorical and largely ineffective, mainly due to the lack of support

and reward systems.

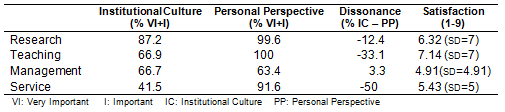

Not surprisingly, the survey findings show that teaching is seen to occupy the

lowest place as to what counts for promotion, whereas personal values signal

the desire for a more balanced and holistic appreciation of academic work (Table

II). Moreover, teaching (along with service) is perceived to be given less importance

than non-academic factors like belonging to groups of influence and family/friendship

ties, which indicates the existence of “political scripts” to deal

with tensions between private and organizational interests, often resting in

alliances operating informally and invisibly through “gamesmanship and

other forms of wheeling and dealing” (Morgan, 2006, p. 204). Overall,

satisfaction with career advancement is not high (5.4/ SD=2.54).

Table II. Career progression factors

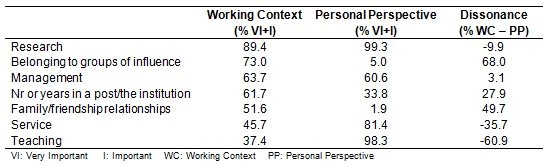

Values incongruence within teaching and research become evident in the respondents’

views about what is and should be assessed as regards quality (Tables III and

IV).

In our institution teaching quality is assessed every semester on the basis

of a student feedback questionnaire focused on instructional aspects. Our survey

presented a list of quality criteria that included those aspects but also other

criteria related to learner-centeredness and a ‘scholarship of teaching

and learning’ (SoTL). As regards the criteria presented, negative dissonance

between institutional and personal values ranges from -31.9% to -73.3% (Table

III). Dissonance increases as we move from teacher-dependent instructional aspects

(appropriateness of objetives, contents, methodologies and assessement) to aspects

that are more learner/interaction-dependent (student involvement/participation,

relevance of learning and teacher-student relationships), and to those that

are related to SoTL – pedagogical training, innovation and inquiry, dissemination

of practice, and peer collaboration.

Table III. Teaching quality assessment

Even though SoTL fosters the transformation of teaching cultures by enhancing

responsive professional collegiality, continuing professional development and

bottom-up quality improvement strategies (Boyer, 1990; Shulman, 2004), it has

played a marginal role in institutional agendas (see Vieira, 2009) and institutions

do not have established academic development systems. This might explain why

most respondents consider the impact of teaching assessments on campus-wide

change to be low.

The respondents’ average satisfaction with teaching assessment results

is moderate (6.97/ SD=1.55) and those results are perceived to have some impact

on their personal practices. Given the existence of values incongruence as regards

criteria for assessing teaching quality (Table III above), we might ask: Do

their practices conform to or move beyond the perceived assessment criteria?

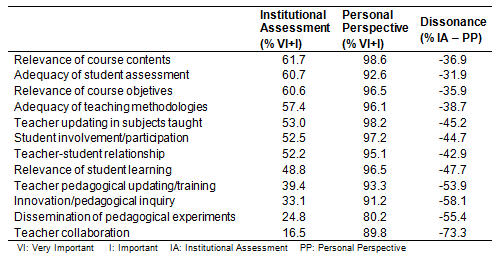

As for the assessment of research quality in working contexts, which is done

every year, dissonance is globally lower than in the case of teaching (Table

IV).

Table IV. Research quality assessment

Perceived and ideal values tend to converge in aspects that have been emphasized

as indicators of excellence in external assessments and fund allocation policies–quantity

of publications, fund raising, quantitative and discipline-based research, inter/national

impact, and publishing in English. However, dissonance increases (ranging from

-31.4% to -50%) as to the importance of qualitative and multi/ interdisciplinary

research, the local impact and social relevance of research, and dissemination

in the native language. Many academics appear to wish that these aspects were

more valued, and in fact there has been controversy about the way research policies

have disregarded them. Yet, their average level of satisfaction with assessment

results is not low (6.03/ SD=1.92) and most of them feel

that those results have an impact on their research practices. Again, we might

ask: Do their research practices conform to or move beyond the perceived dominant

criteria?

The results presented so far indicate that although most respondents are moderately

satisfied with their own teaching and research, their ideal perspectives on

the quality of both and on the role of teaching in career advancement diverge

significantly from perceived demands, and there seems to be a predisposition

to embrace a more holistic understanding of academic work.

The tension between real and ideal emerged in the interviews. In coping with

“the rules of the game”, attitudes vary from conformity to resistance,

but the consequences of swimming with or against the tide are always assumed:

(...) I don’t think I should measure what I deserve [in terms of career promotion] according to the [teaching] work I did, or my investment, or my dedication only, because if I do not have a product... The institutional culture is as it is, I knew it was like that and so I knew the rules of the game... (I9).

The pressure [from institutional demands] is enormous. The pressure is enormous. I have been very affected by that pressure. Now I realize that in order to survive the best thing is... I mean... to understand the rules of the game... but not let myself be totally conditioned by them, and so what I try to do is a bit like... walking between the rain drops, you see? (...) Sometimes I do not agree with demands and I have to take a stand and say I’m against them, but I never put myself in the position of not fulfilling minimum obligations and rules. (I2).

When the interviews were conducted, a new internal system for assessing faculty productivity in all areas of academic work was being devised, and while the interviewees felt that they would probably have to adjust to that system, they also feared its consequences on their personal value systems and the relevance of their work. The following account comes from a teacher trainer who had been integrating service and research by visiting schools and working with schoolteachers:

(...) [the new evaluation system] may oblige me to be more rational, stop doing what I see as a priority for the university and society, and think about what is a priority for keeping my job. That’s life... (...) For example, it will no longer make sense to visit thirty schools as I did last year... It would rather make more sense to follow the six schools I am now working with in teacher education (...). Of course it makes sense to me (...) as a social response [to the needs of schools] but it does’t make sense in terms of research benefits. (I5).

Although no one denied the value of research and publication, what is personally relevant may not count much according to dominant policies:

The publication of books is not valued. Well, I don’t care. If studies are developed by me or with my collaboration, and they cannot be published as articles abroad, which is now the band-wagon, I don’t worry a bit... I am about to publish a book. I know it counts for nothing but I don’t care because it’s a personal imperative to publish this book, which will reach a lot of people. It counts for nothing in my career, not even in our research unit or the research group I belong to, but that’s no reason why I shouldn’t publish it. (I1).

Actually, the social relevance of mainstream research is called into question:

I am not sure that the research we do here in our college contributes in some way to the collective good and to a better, more just society where people can understand one another... that is, a humanist society... (I4).

Values incongruence pervades academics’ experience of teaching and research. This is also true, as we will see next, of working climate, relationships, and leadership.

3.2 Working climate, relationships, and leadership: what is (not) valued

Average satisfaction with the working climate and relationships in working contexts

is not high (5.69/ SD=2.08) and negative dissonance was found especially as

regards a democratic culture of respect, professional motivation and a sense

of job security (Table V).

Table V. Climate and relationships

Interviewees also took a critical stance towards their working environments and discontent was often voiced. When reporting on positive and negative episodes from experience, they focused on issues of support, mutual respect, justice and integrity and their impact on self-esteem, morale and proactiveness. In some cases, the effects of negative experiences are devastating. One of the interviewees, after being accused of seeking attention because s/he organized an event for the department, felt that s/he had been disrespected both personally and professionally, and decided to assume “the attitude of being like a shadow at work”:

(...) the situation was discussed in my department when I was not there, and I never had a word from the person who caused this mess, and I did not know what had happened... I never had a say in the matter, before, during or afterwards. (...) At the time, it made me... I was going mad. After that I realized that any personal initiative for my students, the department or myself, even with the best of intentions, can be misinterpreted in unimaginable ways. So from then on I assumed the attitude of being like a shadow at work. (I8)

Not feeling valued by peers may lead to isolation and disengagement, which hinders the achievement of collective institutional goals (Gappa et al., 2007). Furthermore, workplace environments characterized by poor communication and low participation in decision-making may foster a climate of mistrust and unspoken fear, leading to conformity, discontent and disempowerment:

(...) there are many situations in which I keep silent and many people keep silent because they know that if they don’t keep silent they will have problems. If they use their freedom of thought they will probably have some problems. (I4)

In the department meetings I feel that most people take an acquiescent position, thinking: “What does the head of the department think? I will vote in accord with that”... instead of assuming a clear position, and trusting the head of department, and thinking that if they assume a position that is contrary to his, they will not suffer any retaliation for it. I think people live in that fear. (I7)

In my college (...) everthing is done behind scenes. (...) there is a very small group of people who are really in charge and make decisions for others, and there is nothing you can do about it. (...) Obviously, when those decisions have to do with you, it makes you feel down. But you cannot talk about it because if you talk it will get to the director. So, in a way there is a climate of... I do not want to use the term fear, but there is not a climate of openness, dialogue, clarification of doubts... Decisions are often made without taking into consideration the people in question... and this causes some discomfort and discontent. (I6)

The above accounts draw our attention to leadership, since it influences the working atmosphere. Actually, the survey results indicate that satisfaction with leadership is quite low (4.88/ SD=2,13) and a significant negative mismatch is observed between what academics experience and value, particularly as regards collegiality and equity (Table VI). These aspects have been threatened by a growing managerial type of governance that entails the centralization of political and strategic power (see Santiago and Carvalho 2012), even though the stated mission of the university advocates freedom of thought, plurality of ideas, humanism, creativity, innovation, sustainable development, well-being, and solidarity. When asked about whether that mission is reflected in practice, most interviewees showed signs of scepticism and disbelief. A schism between rethoric and reality, as well as between “academic managers” (they) and “managed academics” (we), surfaced in their discourse (cf. Winter, 2009).

Table VI. Leadership qualities

Personal commitment to collective welfare was also pointed out as crucial. By taking a critical stance towards negative facets of the institutional culture, academics can become cultural drivers and leaders of institutional change, which means that “the interface between leadership and ownership is a critical one” (Gordon, 2010, p. 101):

People need to have some sense of agency, to realize that they have some responsibility for changing the working climate, and I think people often tend to say “poor me”, “I’m the victim”, “I’m a just a poor guy in the middle of all this”, and they do not assume the responsibility they have, right? (...) I believe that constraints should raise our awareness and our ability to design our own paths, to know where we can go, and if we have a rock in the way we should pull it aside or go around it. I think there are conditions in which to enact the mission. (I3)

Dealing with conflicting rationalities may, however, induce a sense of disempowerment and create the need to be told what (not) to do, which will reinforce the culture that is criticized for being alien to one’s aspirations and efforts. The interviewee who claimed that publishing a book that counts for nothing was a personal imperative also stated the following:

We have always been very autonomous. There was never anyone telling us what to do and perhaps that’s one of the problems. (...) In this college there was never a policy, a policy of growth or criteria towards this or that area, either in teaching or research. (I1)

Overall, this second set of findings suggests that there is a person-organization misfit as regards representations of working climate, relationships and leadership. Working contexts appear to suppress rather than encourage dissent, open communication and the negotiation of perspectives, which reinforces the need for further research into life experience on campus as a way to open up the road for reflection and debate towards a culture of respect for diversity. What seems to constrain the development of institutional self-inquiry also justifies its potential relevance.

IV. Conclusions and implications

Rather than presenting a holographic view of the institutional culture, academics’

representations of life on campus reveal that personal values differ significantly

from perceived institutional values as regards teaching, research, working climate,

relationships, and leadership. This is evident in the survey data and in interview

accounts where interviewees present “narratives of constraint” but

also “narratives of growth” as they struggle for what makes their

work meaningful (O’Meara et al., 2008). Discontent seems to co-exist with

efforts to pursue one’s cherished values while realizing that institutional

priorities may run counter to ideals. This duality seems important to understand

how academics operate in complex settings under pressure, and attention must

be paid to whether and how dissent can be integrated into a dialogical framework

that accomodates and promotes diversity (Gordon, 2010). Values incongruence

may create “identity schisms” (Winter, 2009) as well as “a

latent tendency [of institutions] to move in diverse directions and sometimes

fall apart” (Morgan, 2006, p. 203). Because rationality is always interest

based and political, competing rationalities cannot be ignored if we are to

understand how institutions develop.

Rather than suppressing diversity and favoring dogma, institutions probabaly

need to acknowledge and explore dissonance as a potential source of energy requiring

pluralist, learning-oriented management, enacted by leaders who have “a

keen ability to be aware of conflict-prone areas, to read the latent tendencies

and pressures beneath the surface actions of organizational life, and to initiate

appropriate responses” (Morgan, 2006, p. 198-199). Protecting the integrity

of academic work by enhancing more inclusive management practices (Kenny, 2009),

as well as acknowledging different forms of scholarship and recognizing the

need for differentiated career paths, would promote “a multi-vocal institutional

identity” (Winter, 2009, p. 128) and allow faculty to work “more

on a dialogical frame than on a confrontational frame” (Bergquist and

Pawlak 2008, p. 238). This implies some resistance to managerial modes of governance

where collegiality and professional autonomy are neutralized and where institutional

goals and strategies are defined within a narrow view of productivity and quality.

Billot (2010) argues that nowadays there is a fine line between academic and

institutional identity, meaning that staff need to be flexible and adapt to

new demands by “grappling with a fluid identity” (p. 718) rather

than hanging on to “imagined identities” based on past values that

are not aligned with real circumstances, like collegiality, collaborative management

and academic freedom (p. 712). In fact, research seems to indicate that “while

there are increasing social demands being placed on higher education there remains

a strong commitment to autonomy, independence and academic freedom, which quality

assurance procedures sometimes rub up against” (Harvey and Williams, 2010,

p. 107). Should we then abandon “old” values? In exchange for what?

Whatever our answer is, self-renewing academics are value-driven and future-oriented.

Ideal perspectives, like those we found in our study, far from being exclusively

based on the past (which was not idyllic anyway!), might portray an imagined

future and fuel transformation. This seems particularly important if we want

to reframe higher education purposes with reference to its social usefulness

for serving the common good in the best interests of humanity (Barnett and Maxwell

2008; Henkel, 2007). Can higher education be socially useful if academics’

aspirations are overlooked and life on campus becomes socially degraded?

Going back to the question posed by Schostak and Schostak (2008, p. 250)—What

sort of community is desired?—our study reveals conflicting views and

perhaps irresolvable tensions as regards life in academe. Acknowledging the

importance of dissonance may be the first step towards empowering faculty to

negotiate understandings of what their community is and might be. This means

that institution-specific inquiry into academic experience should not only be

expanded but also become part of the strategic (re)definition of institutional

growth policies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the colleagues who participated in the study and

those who commented in a preliminary version of the survey questionnaire. The

study was funded by the Research Center of Education (University of Minho, Institute

of Education, Braga-Portugal; Project PEst-OE/CED/UI1661/2014,CIEd-UM).

References

Altbach, P. G., Reisberg, L. & Rumbley, L. E. (2009). Trends in global

higher education: Tracking an academic revolution. Report on the UNESCO

2009 World Conference on Higher Education, Paris. Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=59371&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

Barnett, R. (1997). Realizing the university. London: Institute of

Education, University of London.

Barnett, R. & Maxwell, N. (Eds.) (2008). Wisdom in the university.

Milton Park: Routledge.

Bergquist, W. & Pawlak, K. (2008). Engaging the six cultures of the

academy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Billot, J. (2010). The imagined and the real: Identifying the tensions for academic

identity. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(6),

709-21.

Boyer, E. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate.

Princeton: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Coaldrake, P. & Stedman, L. (1999). Academic work on the twenty-first

century: Changing roles and policies. Commonwealth of Australia 1999: Higher

Education Division Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs-Occasional

Paper Series.

Courtney, K. (2013). Adapting higher education through changes in academic work.

Higher Education Quaterly, 67(1), 40-55.

Ditton, M. J. (2009). How social relationships influence academic health in

the ‘enterprise university’: An insight into productivity of knowledge

workers. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(2),

151-64.

Fredman. N. & Doughney, J. (2012). Academic dissatisfaction, managerial

change and neo-liberalism. Higher Education, 64, 41-58.

Gapa, J. M., Austin, A. E. & Trice, A. G. (2007). Rethinking faculty work:

Higher educations’ strategic imperative. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Gordon, G. (2010). The roles of leadership and ownership in building and effective

quality culture. Quality in Higher Education, 8(1), 97-106.

Gottlieb, E. & Keith, B. (1997). The academic research-teaching nexus in

eight advanced-industrialized countries. Higher Education, 34, 397-420.

Henkel, M. (2007). Can academic autonomy survive in the knowledge society? A

perspective from Britain. Higher Education Research & Development,

26(1), 87-99.

Harvey, L. & Williams, J. (2010). Fifteen years of quality in higher education

(Part Two). Quality in Higher Education, 16(2), 81-113.

Johnsrud, L. (2002). Measuring the quality of faculty and administrative worklife:

Implications for college and university campuses. Research in Higher Education,

43(3), 379-395.

Kenny, J. D. (2009). Managing a modern university: Is it time for a rethink?

Higher Education Research & Development, 28(6), 629-42.

Locke, W. & Bennion, A. (2010). The changing academic profession in

the UK and beyond. Research Report published by Universities UK. Retrieved

from http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/Publications/Pages/TheChangingAcademicProfession.aspx

Maison, S. & Schapper, J. (2012). Constructing teaching and research relations

from the top: An analysis of senior manager discourses on research-led teaching.

Higher Education, 64, 473-487.

McInnis, C. (2010). Changing academic work roles: The everyday realities challenging

quality in teaching. Quality in Higher Education, 6(2), 143-52.

Meek, V. L., Teichler, U. & Kearney, M.-L. (Eds.) (2009). Higher education,

research and innovation: Changing dynamics. Report on the UNESCO

Forum on Higher Education, Research and Knowledge 2001-2009 (Kassel, ICHER).

Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=59371&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

Morgan, G. (2006). Images of organization. Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Morley, L. (2003). Quality and power in higher education. Maidenhead:

SRHE & OUP.

O’Meara, K., Terosky, A. L. & Neumann, A. (2008). Faculty careers

and work lives: A professional growth perspective. San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Santiago, R. & Carvalho, T. (2008). Academics in a new work environment:

The impact of new public management on work conditions. Higher Education

Quaterly, 62(3), 204-223.

Santiago, R. & Carvalho, T. (2012). Managerialism rethorics in Portuguese

higher education. Minerva, 50, 511-532.

Santos, B. S. (2008). A universidade no século XXI: Para uma reforma

democrática e emancipatória da universidade. In B. S. Santos

& N. A. Filho (Eds.), A universidade no século XXI: Para uma universidade

nova (pp. 15-78). Coimbra, PT: Almedina.

Schein, E. H. (2010, 4th edn.). Organizational culture and leadership.

San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schostak, J. & Schostak, J. (2008). Radical research-Designing, developing

and writing research to make a difference. London: Routledge.

Shulman, L. (2004). Teaching as community property-Essays on higher education.

San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Teichler, U. & Yagci, Y. (2009). Changing challenges of academic work: Concepts

and observations. In V. L. Meek, U. Teichler & M.-L. Kearney (Eds.), Higher

education, research and innovation: Changing dynamics. Report on the UNESCO

Forum on Higher Education, Research and Knowledge 2001-2009 (Kassel, ICHER).

Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=59371&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

Twale, D. & DeLuca, B. (2008). Faculty incivility-The rise of the academic

bully culture and what to do about it. San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Vieira, F. (2009). Developing the scholarship of pedagogy-Pathfinding in adverse

settigs. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(2),

10–21.

Waitere, H. J., Wright, J., Tremaine, M., Brown, S. & Pausé, C. J.

(2011). Choosing whether to resist or reinforce the new managerialism: The impact

of performance-based research funding on academic identity. Higher Education

Research & Development, 30(2), 205-17.

Winter, R. (2009). Academic manager or managed academic? Academic identity schisms

in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,

31(2), 121-31.

Please cite the source as:

Vieira, F., Morgado, J. C., Almeida, J., Silva, M. y Sá, J. (2014).Representations

of academic life: Institutional and personal values. Revista Electrónica

de Investigación Educativa, 16(2), 52-67. Retrieved from

http://redie.uabc.mx/vol16no2/contents-vieiraetal.html