between 25 and 60 years of age

Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 11, No. 2, 2009

Increase in Schooling of Mexico’s Economically Active

Population and Its Effect on Employment

Status and Income, 1992-20041

María de Ibarrola

mdei@prodigy.net.mx

Departamento de Investigaciones Educativas

Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados

Instituto Politécnico Nacional

Calzada de los Tenorios 235

Colonia Granjas Coapa, 14330

México, D.F., México

(Received: June 3, 2009; accepted for publishing: July 23, 2009)

Abstract

This paper presents some effects of the remarkable increase in schooling in

Mexico on the employment status of the country’s non-agricultural, economically-active

population (EAP) between the ages of 24 and 60. We analyze

the distribution of this population by categories, including the level of schooling

attained, hourly earnings and participation in one of the country’s five

different labor sectors: two informal (self-employed workers and managers of

informal microenterprises) and three formal (public sector, companies in the

industrial sector, and service sector companies). Data from 1992 to 2004 are

compared. The results derive from a database developed for Mexico as part of

several national studies conducted by the Information System on Educational

Trends in Latin America (SITEAL for its acronym in Spanish),

based on the National Survey of Income-Expenditure.

Keywords: Academic achievement, educational attainment, income, labor

market.

Introduction

The increase in schooling in Mexico has been one of the most impressive educational

achievements in the country, as an analysis of historical data easily demonstrates,

and as has been registered by some researchers (Mercado and Planas, 2005). The

effects of this increase in the educational level of the economically active

population (EAP) in the country are evident. The latest

data from the Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI—acronym

in Spanish, n.d.) indicate that average years of schooling of the country’s

EAP rose from 6.8 in 1992 to 8.4 in 2004, and reached

9.1 years of school in 2009.

Despite this there are few studies drawn from national statistics

that would allow a systematized and longitudinal analysis of the impact of this

increase on the labor distribution of the EAP in the country,

according to differences in formality or informality among the occupational

sectors as well as the differences in income that result from this double condition.

In 2006, UNESCO’s Information System on Educational

Trends in Latin America (SITEAL--acronym in Spanish, n.d.)

systematized a series of common indicators on schooling, average hourly income,

age, sex and size of locality, based on five occupational sectors—two

informal and three formal—in which the EAP of several

countries is pinpointed. In order to facilitate comparison, data were obtained

from the National Survey of Household Income and Expenditures or its

equivalent for the years 1992, 1996, 2002 and 2004. The present analysis was

built based on a selection of these data for Mexico.2

The complex relationship between educational level and work

In a recently published textbook, Dr. Martin Carnoy (2006) briefly and simply

describes the history of the relationships between education and work and how

economists have conceived them. It is surprising that the perception and conceptualization

of the differences and inequalities between workers with regard to their education,

skills and abilities—despite having been identified by many classic authors,

from Adam Smith on—was only taken up again theoretically

as recently as the middle of the last century with the theory of human capital,

a term coined so successfully by Theodore Schultz.3

With this theory it has been common to reduce human capital to years of schooling

attained, which is measured in terms of completed grade levels. Research in

this area has found some consistent large-scale results; for example, the positive

correlations between higher educational levels in the workforce of a country

and its productivity; the fact that higher educational levels are positively

correlated to higher incomes and job positions, that is, the proportionately

higher rates of return that are generated by schooling, not including its direct

and indirect costs. These macro results have, with some impunity, transformed

the correlation into causality, reinforcing the common-sense belief about the

economic benefits of education.

Various researchers—educational economists and educational sociologists—have

questioned this mechanistic vision (Levin and Kelley, 1994). Gary Becker (1964,

p. 17) states that “education and training are the most important investment

in human capital”; however, he also recognizes the influence of the family

in the formation of the worker as well as the contribution made to the worker’s

development by job-site learning and training.

A line of research initiated in 1986 (Hanushek, 1986; Hanushek and Woesman,

2007) proposes distinguishing between quality of education and schooling.

It is not the hours spent “seat-warming” in a classroom that influence

economic development, but knowledge and skills, which can indeed be developed

in school, but which can also be fostered by the family, peers and culture.

Schools in and of themselves are not the answer. Other factors have a significant

impact on earnings and growth, on economic institutions, the openness of the

economy, property systems, and so on. Without them, education and skills will

not have the desired impact on economic performance.

An important part of the arguments and premises that take issue with human capital

theory relate to the theory of reproduction. The now classic texts of Baudelot

and Establet (1975) and of Bourdieu and Passeron (1964) focus on the unequal

distribution of opportunities of access to education, which is closely correlated

to preexisting socioeconomic inequalities. Recent studies posit that the increase

in educational opportunities has shifted the effects of socioeconomic inequalities

onto areas internal to schooling: student failure; delays that result in students

pursuing grade levels or degrees at more advanced ages; the possibilities of

finishing each academic cycle in the allotted time; grades; and the type of

educational institution to which the student has access, among other aspects

that continue to demonstrate such correlations (Schwartzman, 2004; Tenti and

Cervini, 2004).

Other authors focus on the limitations of the labor market: education does not

create jobs, they argue, and those who attain relatively higher levels of schooling

can, if anything, go to the front of the waiting line for employment; they will

be the last to lose their jobs, although they may possibly experience wage reductions,

or perhaps become underemployed or join the ranks of unemployed college graduates

and suffer the “devaluation” of their educational degrees in an

increasingly inflationary degree market (National Association of Universities

and Institutions of Higher Education [ANUIES, acronym

in Spanish], 2003; Muñoz Izquierdo, 2001; Carnoy, 2005).

Income, meanwhile, does not depend on the worker’s educational level,

but on his/her position in the job market and in the company organization (Levin

and Nelly, 1994). As various authors have demonstrated, including Muñoz

Izquierdo (1996), Hualde and Serrano (2005) and Planas (2008), among others,

the role education plays in work, employment or income varies according to the

economic period in question, the geographical region, the economic sector, the

individual’s gender and age and even the history and culture of the companies

themselves.

In a specific job space, the same college degree does not guarantee the same

high salary or better job position to all those who hold it (De Ibarrola and

Reynaga, 1983), nor does a degree from a technical school ensure getting a job

related to the field of studies (De Ibarrola, 1994; National Technical and Vocational

Education School [Conalep, acronym in Spanish], 2006). Moreover, to the extent

that schooling is distributed more evenly among the population, as is the case

with elementary and junior high school, it ceases to be a causal variable of

differences in income and job position, at least in well-defined sectors of

the labor market (De Ibarrola, 2004a).

Labor markets in Mexico

Most Mexican researchers who analyze the relationship between educational level

and employment concur in referring to job markets and contend that

their heterogeneous character plays an important role in the nature of the relationships

established between said markets and schooling (Reynaga, 2003). Due to limitations

of space for this article, aspects of formality or informality and other characterizations

of the heterogeneous and unequal structure of labor markets in Mexico are not

described, as they have been posited and discussed in depth in other studies

(De Ibarrola, 1988, 1994, 2004a, 2004b).

In this paper we accept the general distinction of heterogeneity between formal

and informal sector, and the five occupational sectors: two informal

sectors (self-employed and microenterprises that employ less than five workers)

and three formal sectors (public sector, large companies in the industrial sector

and large companies in the service sector) that are identified by the available

database and whose operational definition respects the main criteria of the

authors that are identified in the above-cited studies. It should be noted that

it is not the aim of this paper to explain the political and economic factors

that contextualize and determine said heterogeneity in countries like Mexico,

or that provide the framework for the relationship between schooling and employment

in the country.

The objective of this article is simple and rather limited:

it seeks to provide national statistical data showing how the increase in schooling

of the economically active population in Mexico between1992 and 2004 was distributed

between the various occupational sectors, defined according to their formality

or informality in the labor market, and the differences in income resulting

from the level of schooling attained and the work sector in which the individual

is employed.4

Two theoretical approaches support the importance of the objective of this article.

The first contends that the country’s increase in schooling is not derived

from a rational planning based on the availability of jobs for different types

of training, nor does it respond to the qualification requirements for (generic)

development. The increase in schooling has been a product of the tensions and

contradictions between governmental proposals, aimed in great measure at boosting

education in accordance with a (certain) vision of the development needs of

the country or the (supposed) demands of the labor market; of the limited vision

of labor sectors; of the demands and aspirations of young people and their families;

and of the possibilities of educational institutions in a context characterized

by the existence of heterogeneous and unequal labor markets (De Ibarrola, 2009).

This is not to ignore the fact that educational opportunities, particularly

following completion of compulsory education, are clearly insufficient.

The second approach divides interpretations of the effects of increased schooling

on earnings and employment into two main arguments:

a) The first, which is related particularly to the growth of higher education,

attributes the failure of college graduates to find employment in professional

positions commensurate with their level of schooling to the dysfunctionality

of the educational system (ANUIES, 2003).

b) The second postulates that the increase in schooling (at all levels) has

had a significant supply effect by creating an increasingly better-educated

labor force that is expressed as follows: “the increase in education has

been extended to all employment categories as a result of the strong effect

of educational supply, relatively independent of a parallel development of job

categories” (Béduwé and Planas, 2002, p. 58). The educated

population is spread throughout all occupational sectors and its higher levels

of schooling have been rewarded with the higher relative earnings that the labor

market offers to those with relatively higher educational levels (Béduwé

and Planas, 2002; Flores and Román, 2005; Planas, Román, Flores

and De Ibarrola, 2007).

In none of these cases do the authors analyze the heterogeneity of labor markets.

The data analyzed here, although based on highly aggregated categories, provide

results that take into account important differences between occupational sectors,

thus offering new possibilities for understanding the impact that the growth

in education has had on the employment and earnings attained by the population.

Increase in the educational level of the EAP and

decrease in employment formality

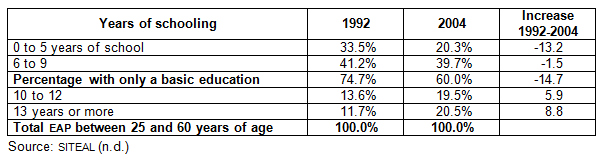

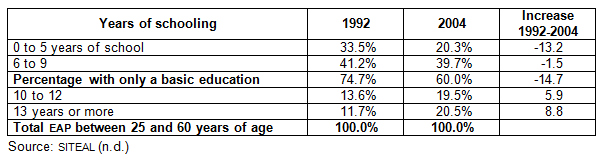

Tables I and II offer two seemingly contradictory types of basic data:

a) Table I shows the remarkable increase in the educational level of the economically

active population in the period under consideration, particularly the decrease

in the EAP that has only achieved a fifth grade education,

and the increase in the EAP with higher education.

Table I. Percentage distribution of schooling for the total

EAP

between 25 and 60 years of age

b) In Table II we can observe a slight decrease in the formal sector, particularly in favor of self-employed workers, as well as greater growth in the public sector than in large corporations of the secondary and service sectors.

Table II. Distribution of the EAP between

the informal and formal

labor sectors 1992-2004

Educational level and insertion in labor market sectors

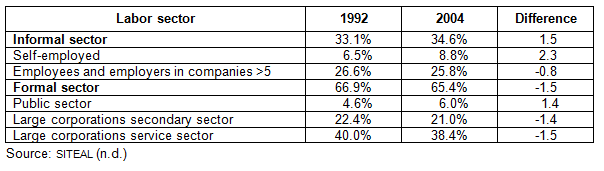

Table III analyzes the distribution by occupational sectors of the population

with incomplete elementary level schooling,5

a demographic which decreased 13.2 percentage points for the total economy during

the period under consideration.

Table III. Percentage of the EAP that

did not complete elementary education

by occupational sector

The EAP with this low educational profile decreased by

just half a percentage point (-0.5) among the self-employed and workers in the

public sector (-0.7). However, it declined significantly among employees and

employers in companies with less than five workers, followed by workers in large

corporations in the secondary and service sectors.

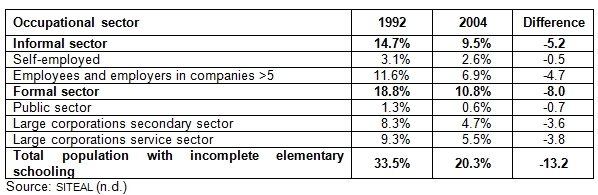

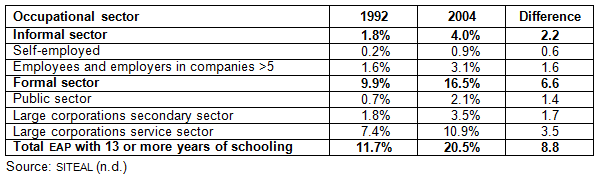

Meanwhile, as can be observed in Table IV, the labor force with more than thirteen

years of schooling—which rose 8.8 percentage points during the period—increased

mainly in the formal service sector and only slightly among the self-employed.

However, the growth in workers with higher education in informal micro-enterprises

was greater than that in the public sector and almost equal to that in the formal

industrial sector. Large corporations in the tertiary sector continued to be

the biggest employers of the population with more than thirteen years of schooling.

Table IV. Percentage of the EAP with

13 or more years of education

by occupational sector

It should be noted—although the data is not displayed thus in the charts—that

the informal sector in 1992 comprised 33.1% of the total and 43.8% of the EAP

with incomplete elementary level schooling, but only 15.3% of the labor force

with higher education. By contrast, during the same year, the formal sector

contained 65.4% of the total EAP, and while it included

56.2% of the population without an elementary education, it also concentrated

84.4% of the economically active population with higher education. However,

by 2004 the distribution had changed, in particular due to the increase in workers

with higher education in the informal sector, which eventually captured 19.5%

of the work force with thirteen or more years of schooling.

In both years, employees with the higher level of schooling were concentrated

in large corporations in the service sector, but this concentration declined

from 63.2% to 53.1% during the period, while the public sector nearly tripled

its proportion of workers with more than thirteen years of schooling.

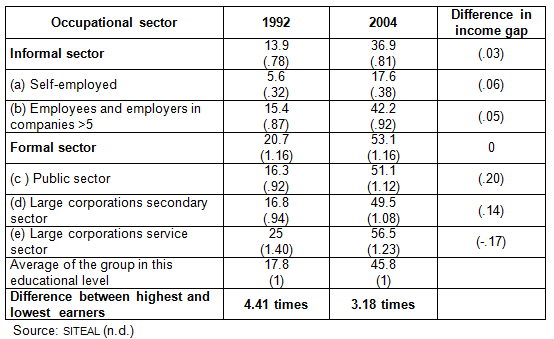

Variation in hourly earnings according to economic sector

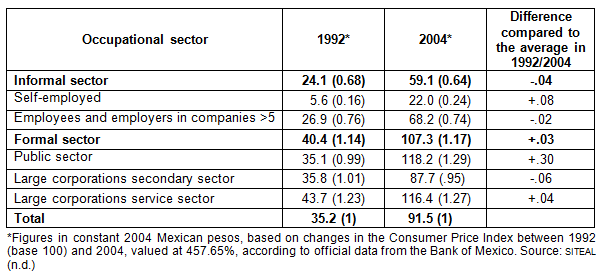

As indicated in Table V, income is significantly affected by the economic sector

in which the worker is employed. In the years for which we have information,

the income of workers in the informal sector represents only between 0.64 and

0.68 of the national average for income for those dates, while the incomes of

those in the formal sector were between 1.23 and 1.29 times the average. Those

with the lowest earnings were self-employed,6

whose income did not amount to even a fifth of the national average. In contrast,

those who surpassed the average were, in first place, employees of the service

sector, followed by workers in the public sector.

Table V. Distribution of hourly earnings by sector of the economy

and income

gap () in relation to the average hourly income of the total

It is interesting to note that formal secondary sector workers saw an increase

in the gap between their earnings and the average formal sector earnings: in

2004 their income was lower than the overall average, approaching that of employees

and employers of informal microenterprises.

Moreover, those who most increased their income were public sector workers,

who by 2004 were, on average, the highest paid. This is due, without a doubt,

to all of the policies implemented to support the poorest sectors of the country;

the self-employed tripled their meager income during the period, although they

continue to be—by definition—the workers with lowest earnings.

The role of schooling

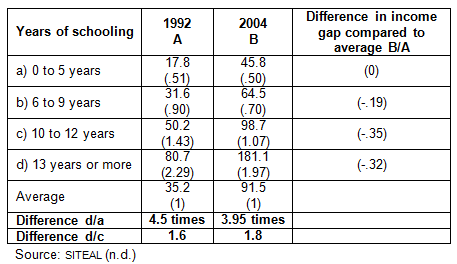

The distribution of hourly earnings by schooling attained is highly significant:

Table VI shows a steady increase in average earnings as the level of schooling

attained rises. The income difference between those that have higher education

and those who failed to complete their primary education is very high in the

two years indicated: 4.5 times higher earnings for the college educated group

in 1992, although in 2004 the difference fell to 3.9. The income difference

between those with higher education and the level of schooling immediately below

them, a 10th to 12th grade education, is almost double for the college educated:

1.83 times higher in 2004 and in 1992, 1.6 times higher.

Table VI. Distribution of hourly earnings by educational level

attained and

income gap () in relation to the overall average (2004 Mexican pesos)

Impact of schooling and

occupational sector on income

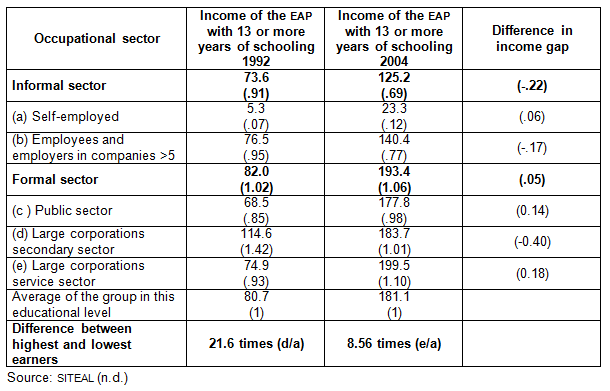

It is also clear that the occupational sector in which the EAP

is employed affects the income gap between those with higher education and those

who barely finished their elementary education, as can be observed in Table

VII.

Table VII. Distribution

of hourly earnings by economic sector and income gap ()

in relation to the average of the total of the group with

13 or more years of schooling (2004 Mexican pesos)

The data in Table VII show that

the average income of workers with thirteen years or more of schooling varies

significantly depending on the occupational sector. In 1992 workers in large

corporations in the secondary sector far outperformed the category average,

whereas the self-employed, despite having the same high level of education,

were the farthest from the group’s average income, earning 21.6 times

less than workers in the industrial sector. By 2004, this gap was reduced by

almost two thirds. Throughout the period, however, the gap in income compared

with the average also increased for those working in microenterprises in the

informal sector and, in particular, for those working in large corporations

in the secondary sector, as they clearly lost the big advantage they had had

with respect to workers in the other sectors.

The figures also show a significant increase in salary for workers in the public

sector, although proportional to their lower earnings in relation to those of

the other occupational sectors. Surprisingly, the greatest relative increase

during the period went to the self-employed.

In Table VIII income by occupational sector for those who only studied up to

the fifth grade of elementary school is analyzed, with the following results:

Table VIII. Hourly

income distribution by economic sector and income gap ()

in relation to the average of the total for the group with less than 5 years

of

elementary school education (2004 Mexican pesos).

There is a marked contrast between

workers employed by large corporations in the service sector (the highest earners)

and the self-employed (the lowest earners). The former earned 4.42 times more

in 1992, while in 2004 their income was 3.21 times higher, due to the reduction

in income gap for corporations in the tertiary sector. Once again we can observe

the wage increase for workers in the public sector. However, the income gap

between occupational sectors for those with this low educational level was not

as pronounced in either of the two years studied as was observed for the group

who had some higher education.

Table IX examines the income gap between those with higher or lower levels of

schooling within each occupational sector, which proves to be the source of

the most significant gap, although it varies between sectors and throughout

the period under consideration. The largest gap occurred in large companies

in the secondary sector during 1992, when workers with more than thirteen years

of schooling employed in said sector earned 6.8 times the income of those in

the same sector with no more than five years of schooling. In the public sector

those with the highest educational levels earned 4.18 times more than those

with the least schooling. By 2004, the size of the gap was reduced by almost

half in all of the sectors, particularly in large corporations in the industrial

sector, although it widened in large companies in the service sector and among

the self-employed (who in 1992 earned even less than those who did not finish

elementary school).

Table IX. Income gap

between those with the most schooling

(13 years or more) and those with the least (5 years or less), by occupational

sector in 1992 and 2004

Summary and Conclusions

This paper just touches a very small piece of the surface of the complex and

multidimensional puzzle that is the relationship between education and work

in Mexico.

Many facets were not analyzed here: the younger populace in the country, workers

in the primary sector, gender impact, the size of localities, to mention a few.

We also did not address the fluctuations of the economy: inflation reached 457%

in the period under consideration; between 1994 and 1995 in particular, the

economic crisis was brutal, with a currency devaluation of 100% in 1994. By

1999 a recovery was underway that was reflected in the better wages recorded

for 2004 in all occupational sectors. However, starting in 2007 a new crisis

emerged that is now recognized as far worse than the previous one. The dramatic

fall of the gross domestic product (GDP), a more severe

recession than that of 1994-1995, the serious loss of formal jobs, the decline

of economic activity in all sectors and in earnings, together with the rise

in poverty (Acosta, 2009), mark a new economic period that clearly limits the

scope of the data analyzed here to a very specific period and demonstrates the

great sensitivity of income to the fluctuations of the economy.

It is, therefore, useful to highlight the contributions of this study:

1) The increase in schooling in the country is undeniable, reflected

in the increasingly higher levels of average schooling of the economically active

population between 25 and 60 years of age from 1992 to 2004, although most of

the active population in this age group (60%) is still below the now compulsory

basic educational level.7

Paradoxically, despite the increase in schooling, the possibility of integration/insertion

in the formal sector of the economy decreased slightly.

2) The differences in education among the population tend to correlate with

the different sectors of the economy identified in this paper: those with less

than five years of schooling tend to be concentrated in the informal sector

among the self-employed and those who achieved thirteen or more years of schooling

in large tertiary sector corporations and in the public sector. But there are

individuals with higher and lower levels of education in all the occupational

sectors, and the increase in schooling is discernible in all of them, even slightly

modifying the proportional distribution among them.

3) In all occupational sectors, those with higher educational levels have significantly

higher average incomes than those with less schooling. (Self-employed individuals

with higher education in 1992 comprise the one exception to this trend.) Therefore,

the increase in schooling is remunerated within all occupational sectors.

4) The difference in income for those with the same level of schooling can be

very high between occupational sectors, particularly for those who have higher

education. Among those with no more than five years of schooling the differences

are not so great.

5) Throughout the period under consideration the income gap between those with

less and those with more schooling tended to decrease. One might conclude that

the increase in the average schooling of the population had a positive effect

on reducing income inequalities; but the fluctuations encountered do not allow

us to infer that we are already facing a trend, especially if one takes into

account more recent economic data.

6) The proportion of the EAP with little schooling decreased

in all occupational sectors, although most significantly in large companies

in the industrial as well as the service sector, which impose academic requirements

on their prospective employees, demanding increasingly better educated workers.

In the public sector, union policies most likely impede calls for higher academic

requirements for the same type of job positions. One of the characteristics

of the informal sector is precisely that there are no educational prerequisites

for joining it.

7) For its part, the EAP with higher education increased

in all sectors and its weight in percentage terms shifted slightly toward the

informal occupational sectors. Without a doubt, a possible explanation could

be the dysfunctionality of the schooling achieved, since 20% of those with the

highest educational level were actually unable to find jobs in the best occupational

sectors. But the fact that they are spread out in other sectors—in particular

among the ranks of the self-employed and microenterprises—should not preclude

their obtainment of higher incomes than those with less schooling. These results

could be explained as an indication of the emergence of new sources of employment

and new professions generated by those with high levels of schooling, but which

fall into the informal sector of the economy. A more complete analysis would

require a review of the performance of the rate of return on the investment

in education.

8) The sector comprising large industrial companies, despite the rise in educational

level of its employees, was proportionally the most affected throughout the

period in question. The sector continued to attract workers with thirteen or

more years of schooling, despite the fact that their income advantage, compared

with workers with the same educational level in other sectors, decreased markedly.

This could be an indication that the sector has not managed to fully apply its

employees’ higher levels of knowledge to its competitiveness strategies.

It is also the sector that has been hardest hit by trade liberalization in the

country.

9) Large companies in the service sector boasted the largest concentration of

the EAP with higher education for both of the years under

consideration, although their share of highly educated workers declined during

the period, while the public and informal sectors saw corresponding increases

in their numbers of highly schooled workers. The income advantage of workers

in this type of large corporation increased. These are companies that tout the

need for higher educational levels in view of the new knowledge economy, an

approach that many of them are implementing (Planas, 2008), notwithstanding

that even so they are not able to accommodate all the available workers with

higher education.

10) During the period analyzed, the public sector had the greatest relative

increase in terms of the number of workers that it incorporated and in the incorporation

of the EAP with more schooling as well as in terms of

the wage increase of its labor force. Interestingly, at the national level,

based on highly aggregated data, two important polices relating to employees

in the public education sector can be observed: the requirement of a bachelor’s

degree starting in 1984 and the salary adjustments granted to teachers in the

national educational system, who comprise the occupational group with the greatest

salary increase during the last decade (Flores and Román, 2005).

The analyzed data confirm on a macro scale the theoretical warnings about the

limits that heterogeneous occupational sectors—in this case---impose on

schooling per se as a factor of direct impact on labor placement and income,

as was posited at the outset of this study and about which other research has

been conducted. At the same time, we can discern three situations that are important

for the study of the relationship between schooling and work, all three of which

must be examined more deeply in the double context of the heterogeneity of the

country’s labor markets and the rise in educational levels: a) the increase

in schooling in all sectors, b) the possible reduction of income inequality

that is attributable to widely varying educational levels as well as to the

disparities between occupational sectors, to the extent that inequalities of

educational level decrease, and, c) the potential positive effects of schooling

on productivity and income in the different sectors.

Independently of the very poor quality of the schooling attained, as currently

measured and subsequently denounced in the results of international assessments,

the increased presence of a more highly educated population in the informal

sectors allows us to affirm that workers with more than thirteen years of schooling

earn higher average income than those with less education. The increase in the

level of schooling over time would translate into: a) improved skills and higher

levels of knowledge, which in turn would lead to new beneficiaries of education;

b) landing those job positions that are characterized by being the best paid

(presumably because they require higher levels of knowledge); c) better job

performance, or, alternatively, d) the creation of new and more productive jobs,

even in the most disadvantaged sectors.

On the other hand, this situation could also denote, as others have pointed

out (Muñoz, 1996), the shifting of selectivity towards other levels and

its rigorous implementation in the formal occupational sectors. Nevertheless,

a better understanding of its characteristics and significance is essential.

Schooling per se clearly has not solved the problems of the country’s

economic growth or of the heterogeneity of the job markets. But the increase

in schooling operates within the unequal occupational sectors in ways and with

effects that make it imperative that it be analyzed more rigorously and in greater

depth.

References

Acosta, C. (2009, 31 de julio). Vamos bien en materia económica.

Retrieved October 8, 2009, from http://www.proceso.com.mx/noticias_articulo.php?articulo=71937

Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación

Superior. (2003). Mercado laboral de profesionistas en México

(4 vols.). México: Author.

Baudelot, C. y Establet, R. (1975). La escuela capitalista en Francia.

Mexico: Siglo XXI Editores.

Becker, G. S (1964). Human capital. A theoretical and empirical Analysis

with special reference to education. Chicago: The University of Chicago

Press.

Béduwé C. y Planas, J. (2002). Expansión educativa

y mercado de trabajo. Estudio comparativo realizado en cinco países europeos:

Alemania, España, Francia, Italia, Reino Unido, con referencia a los

Estados Unidos (Informe final de un proyecto financiado por el Programa

Marco de Investigaciones y Desarrollos de la Unión Europea: Ministerio

de trabajos y asuntos sociales). Madrid: Instituto Nacional de las Cualificaciones

de Madrid.

Bourdieu, P. y Passeron, J. C. (1964). Los herederos. Los estudiantes y

la cultural. Mexico: Siglo XXI Editores.

Carnoy, M. (2005). The economics of education. Unpublished document.

Universitat Oberta de Cataluña, Barcelona.

Colegio Nacional de Educación Profesional Técnica. (2006). Seguimiento

de egresados. Informe nacional Encuesta 2001-2004 y 2002-2005. México:

Secretaría de Educación Pública-Colegio Nacional de Educación

Profesional Técnica-RVoxPsolutions.

De Ibarrola, M. (1988). Hacia una re conceptualización de las relaciones

entre el mundo de la educación y el mundo del trabajo en América

Latina. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 2,

9-64.

De Ibarrola, M. (1994). Escuela y trabajo en el sector agropecuario en México.

México: Centro de Investigación y Estudios Avanzados del IPN-Instituto

José María Luís Mora-Porrúa-Facultad Latinoamericana

de Ciencias Sociales.

De Ibarrola, M. (Dir. y Coord). (2004a). Escuela, capacitación y

aprendizaje. La formación de los jóvenes para el trabajo en una

ciudad en transición. Montevideo, Uruguay: Organización Internacional

del Trabajo, Cinterfor.

De Ibarrola, M. (2004b). Paradojas recientes de la educación frente

al mercado de trabajo y la inserción social. Buenos Aires: Instituto

Internacional de Planeamiento de la Educación-RedEtis-ides ( Tendencias

y debates 1).

De Ibarrola, M. (2006). El incremento de la escolaridad en México

y sus efectos sobre el mercado de trabajo en México, 1992-2004.

Informe del caso mexicano. Documento no publicado, SITEAL/UNESCO-IIPE/OEI.

De Ibarrola, M. (en prensa). Priorité a la formation scolaire pour le

travail au Méxique. Tensions et contradictions entre l’Etat, les

secteurs professionnels et les étudiants. Formation Emploi: Revue

Francaise des Sciences Sociales, 108.

De Ibarrola, M. y Reynaga Obregón, S. (1983). Estructura de producción,

mercado de trabajo y escolaridad en México. Revista Latinoamericana

de Estudios Educativos, 13 (3), 11-83.

Flores Elizondo, R. y Román, L. I. (2005). La retribución

de la expansión educativa en el empleo: un análisis sobre México

comparado con la Unión Europea (Reporte de trabajo). Documento no

publicado.

Hanushek, E. A. (1986). The economics of schooling: production and efficiency

in public schools. Journal of Economic Literature, 24, 141-1177.

Hanushek, E. y Wößmann, L. (2007). The role of education quality

in economic growth (Documento de trabajo 4122). Washington, DC:

World Bank.

Hualde, A. y Serrano, A. (2005).

La calidad del empleo de asalariados con educación superior en Tijuana

y Monterrey. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 10,

345- 374.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (s.f.). Consulta

de resultados. Numeralia. Consultado el 8 de octubre de 2009 en:

http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/espanol/proyectos/integracion/inegi324.asp?s=est&c=11722

Levin, H. M y Kelley, C. (1994). Can education do it alone? Economics of

Education Review, 13 (2), 97-108.

Mercado, A. y Planas, J. (2005). Evolución del nivel de estudios de la

oferta de trabajo en México. Una comparación con la Unión

Europea. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 10(25),

315- 343.

Muñoz Izquierdo, C. (1996). Diferenciación institucional de

la educación superior y mercado de trabajo. Seguimiento de egresados

de diferentes instituciones a partir de las universidades de origen y de las

empresas en que trabajan. México: Asociación Nacional de

Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior.

Muñoz Izquierdo, C. (2001). Implicaciones de la escolaridad en la

calidad del empleo en México. México: Universidad Iberoamericana-UNICEF-Cinterfor-Colegio

Nacional de Educación Profesional Técnica.

Planas, J., Mercado, A., Román, I., Flores, R. y De Ibarrola, M. (2007,

enero). Expansión educativa y mercado de trabajo en México,

una comparación con la Unión Europea y Estados Unidos (Reporte

de trabajo). Documento no publicado, Universidad de Guadalajara-ITESO-Cinvestav-Universitat

Autònoma de Barcelona-Université de Toulouse CNAM

Paris.

Planas, J. (2008). El comportamiento de los empleadores mexicanos frente al

crecimiento de la educación. Revista de Educación Superior,

37 (146), 11-40.

Reynaga Obregón, S. (Coord. de Vol.). (2003). La investigación

educativa en México, 1992-2002: Vol. 6. Educación, trabajo, ciencia

y tecnología. México: Consejo Mexicano de Investigación

Educativa.

Schwartzman, S. (2004). Acceso y retrasos en la educación en América

Latina (Serie Debates, No. 1: Equidad en el acceso y la permanencia en

el sistema educativo). Buenos Aires: Sistemas de Información de Tendencias

Educativas en América Latina Consultado el 8 de octubre de 2009 en:

http://www.siteal.iipe-oei.org/modulos/DebatesV1/upload//deb_23/art_13/ART_SimonSchwartzman.pdf

Sistema de Información y Tendencias Educativas en América Latina

(s.f.). Base de datos. Consultado el 8 de octubre de 2009, en: http://www.siteal.org/basededatos/basededatos1.asp

Tenti, E. y Cervini, R. (2004). Notas sobre la masificación de la

escolarización en seis países de América Latina. (Serie:

Debates, No. 1: Equidad en el acceso y la permanencia en el sistema educativo).

Buenos Aires: Sistemas de Información de Tendencias Educativas en América

Latina Consultado el 8 de octubre de 2009 en: http://www.siteal.iipe-oei.org/modulos/DebatesV1/upload//deb_23/art_15/ART_Cervini-Tenti.pdf

1Excerpts

from the Chapter of the Report by Country, unpublished: De Ibarrola, María.

El caso mexicano [The Mexican Case], prepared under contract with SITEAL,

UNESCO-IIPE, OEI (February

2006). Translator’s Note: SITEAL is the Spanish

acronym for the Information System on Educational Trends in Latin America, which

is under the auspices of the International Institute of Educational Planning

(IIPE, acronym in Spanish) of UNESCO

and the Organization of Iberian-American States (OEI,

acronym in Spanish).

2I was asked to draw up the report on Mexico in relation to education and labor markets (De Ibarrola, 2006). It should be noted that the database had some important limitations: it did not include the EAP in the agricultural sector nor workers less than 24 years old. Categories for studying the level of schooling attained, as can be seen in the corresponding section, were highly aggregated, but the importance of the database consisted in the possibility it offered for analyzing five different sectors of the economy, which are described later.

3The first translation into Spanish [of Schultz’ book], Valor económico de la educación (The Economic Value of Education), was issued by UTEHA publishing house (Barcelona) in 1968.

4In this regard, and given the nature of the data, the statistical analyzes are based on percentage distributions and in particular on the differences in earnings for each of the different categories.

5We analyzed only the most extreme categories of educational levels: those who received only five years of schooling or less, and those who had at least one year of higher education (thirteen years or more).

6It should be remembered that a criterion for identifying the self-employed was that their hourly earnings be 30% lower in the distribution of hourly earnings consisting solely of self-employed workers 2.7.

7Translator’s

note: Compulsory education in Mexico, what is known as “educación

básica” is elementary and junior high school, grades 1 through

9, and usually also requires two to three years of preschool as well.

Please cite the source as:

De Ibarrola, M. (2009). Increase

in schooling of Mexico’s economically active population and its effect

on employment status and income, 1992-2004. Revista Electrónica de

Investigación Educativa, 11(2). Retrieved month, day, year,

from http://redie.uabc.mx/vol11no2/contents-deibarrola.html