Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 10, Num. 2, 2008

Faculty Participation in Planning Activities and

it's Relationship with their Vision of the Institution

Juan José Sevilla García

jsevilla@uabc.mx

Instituto de Ingeniería

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California

Blvd. Benito Juárez y Calle de la Normal s/n.

Insurgentes Este, 21280

Mexicali, B. C., México

Jesús Francisco Galaz Fontes

galazfontes@gmail.com

Facultad de Ciencias Humanas

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California

Blvd. Castellón y Lombardo Toledano s/n

Col. Esperanza Agrícola, 21350

Mexicali, Baja California, México

José Luis Arcos Vega

arcos@uabc.mx

Coordinación de Planeación y Desarrollo Institucional

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California

Av. Álvaro Obregón y Julián

Carrillo s/n, Colonia Nueva, 21100

Mexicali, Baja California, México

(Received: August 17, 2007;

accepted for publishing: September 13, 2008)

Abstract

This work took place among academicians in a public state university, it analyzes the posible relation of the academicians’ level of participation in the formulation process of the Comprehensive Institucional Strengthening Program (Programa Integral de Fortalecimiento Institucional, PIFI, in Spanish) and/or the Program for Strengthening High Education Institutions (Programa de Fortaleciemiento de la Dependencia de Educación Superior, PRODES, also in Spanish), with their level of information, their perception of the working environment, administration, decision-making and influence, institutional image and sense of belonging, and work satisfaction. The information used for this analysis was provided by the Organizational Environment Annual Survey (Encuesta Anual de Ambiente Organizacional, EAAO, name in Spanish), which is applied every year to said institution. Results show that academicians who have higher levels of participation also appear to have, in general, a better image of the institution, particularly regarding working environment, level of information and decision-making. Also, those who have a better perception of the institution’s administration, image and pride as well as work satisfaction appear to have higher levels of participation, though the difference is minor. These results are discussed according to the value that the strategic and contextual planning gives to the actors of the organization.

Key words: Cooperative planning, faculty, job satisfaction, institutional administration.

Introduction

The Mexican public university has gone through several stages in the university-state relationship. Since the decade of the 1990s, public policies have sought to base their financing, beyond that of a minimum regular budget, on an evaluation of how the Institutions of Higher Education (IES) are functioning (Rodriguez, 2002).

At the end of the 80s and during the 90s, the Mexican government, through its Subsecretariat of Higher Education and Scientific Research (SESIC), promoted a series of special financing programs: the Fund for the Modernization of Higher Education(FOMES), the Program for Teacher Improvement (PROMEP), The Multiple-Benefit Fund for Enlarging, Modernizing, Maintaining and Equipping Physical Spaces (FAM), the Program of Support for University Development (PROADU), the Program for Normalization of the Administration (PRONAD). These programs have had some novel characteristics regarding the manner of negotiation and assignment of resources to the IES, for example: the pursuit of a specific goal, by means of a single appropriation of resources, not standardized and not involved in the irreducible annual budget; functioning under rules of operation established by the federation, which implies a mechanism for evaluation; and voluntary participation. As Kent, De Vries, Didou and Ramirez (1998) indicate, these programs can have a significant impact on the modification and/or adequation of the mission and vision of the IES, and in the forms of regulation of academic work and institutional governance.

The intent behind these programs has been to improve the quality of higher education, beginning with resources, which, although few and limited, can lead to institutional change. Among the issues to which resources are directed, are the improvement of the performance and the training of career teachers of the IES, modernization of the infrastructure and administrative services, the support of research and the construction and equipping of physical spaces (Lopez and Casillas, 2005).

Considering this diversity of programs having different objectives, the National Education Program 2001-2006 promised that the IES would formulate an Integrated Program of Institutional Improvement (PIFI),1 which would bring together and harmonize all or most of the institutional actions, with the goal of promoting continuing improvement and an assurance of the quality of programs and educational services offered by the IES, as well as its academic/administrative management (Rubio, 2006). Because of this, the PIFI was made up of the Programs for the Improvement of Units of Higher Education (PRODES)2 and of a Program for Improving Institutional Management (PROGES). Beginning in 2001, the IES that decided this, presented successive versions of their PIFI, so that initially, there was adopted a nomenclature based on the magnitude of the modifications made to the program announcement. Under the present federal administration (2006-2012), it takes the name of the year in which it is presented (e.g. PIFI 2008).

Although the application of these policies has been evaluated as productive by the relevant authorities (Rubio, 2006), the results are not homogeneous, and the processes involved should be studied in detail. Some of the present questions relate to the exhausting process and the enormous institutional effort invested (Kent, 2005), in the preponderant attention given to performance indicators, as opposed to the processes that generate them (Gil Anton, 2006); in the level and the quality of the academic communities’ participation in the planning process; in the widening of the quality gap between institutions, in spite of its being something the program seeks to reduce (Navarro, 2005); in the lack of consideration for the different cultures and traditions of each discipline, as well as the missions of the different IES. This tends to homogenize institutional diversity, or even the system of higher education itself, and has implications in the difficulty of meeting a good number of the programs’ short-term objectives (Casillas and Lopez, 2005), because they involve substantial changes in the IES. Moreover, the PIFI represents external forces —international agencies that maneuver a national project— and on the local scene, seek to change the university by decrees and financially-motivated initiatives, so as to obtain external resources. This means an invasion of the university’s autonomy, and is an obstacle to the creativity of its communities in responding to their specific problems (Porter, 2004).

With these funding policies, planning plays a newly-centralized role in the life of the IES, since now, unlike in the immediate past, it is associated with evaluative mechanisms that allow institutions to access extra funds. The exercise and financial implications of the Integrated Program of Institutional Improvement (PIFI) is a clear example of these new conditions (Rubio, 2006).

One aspect that the PIFI claims to promote is the participation of the academic communities that make up the IES, more specifically that of the Units of Higher Education (DES) (Rubio, 2006). Recently, the Sectorial Education Program of the Secretariat of Public Education for the period 2007-2012, has established as one of its purposes, to promote in the IES the planning and formulation of institutional improvement programs in which short-term, medium-term and long-term goals would be established by means of genuinely participative processes involving their key actors (authorities, researchers and teachers, among others), and that these be linked with transparent exercises of evaluation and the rendering of accounts (Secretariat of Public Education, 2007).

The theme of the participation of the different actors in the university communities is important not only from the theoretical perspective of planning (Peterson, 1997); it is also recognized as central at the level of public policy. In a future full of challenges for Higher Education (ES), there is an indisputable need for IES leaders with the knowledge and ability to manage the itinerary in a participative manner as they confront the risks facing them. This means, among other things, the activation of planning mechanisms capable of anticipating and articulating their responses to these major issues, and the presence of structures of governance3 and organizational processes capable of creating appropriate institutional policies of reasonable efficiency and political feasibility.

In the scenario of contemporary higher education, there have emerged some imperative issues associated with the decision-making process, in the efforts of the IES to carry out their missions. These themes are: 1) the momentum of a participatory governance, 2) the necessity for efficient administration, 3) the urgency of adapting to the changing context, and 4) the existence of effective leadership. These issues are interwoven, and are at times moving in opposite directions, such as recognizing the value of broad participation, while at the same time implementing ever-more-efficient processes.

Beyond the challenge of settling on a direction best suited to facing the challenges of the IES (especially public ones), there arises the need for designing an apparatus for appropriate governance. Said in another way, it means that the IES can create effective mechanisms for determining credible, legitimate future priorities that will be accepted by the university community.

“The importance of the governance element should not be underestimated. The “best” plans and strategies are of little use if the campus community —especially the faculty— does not find them legitimate. And they will not be regarded as legitimate —and should not be— if the plans and strategies, regardless of content, are faulty with respect to the process that gives rise to them” (Schuster, Smith, Corak and Yamada, 1994, p.7).

This tension between the orientations of strategic planning and governance usually arises from the use of structures, processes and participants, working in parallel. The challenge consists in reconciling the two domains, interlacing their differences, using the strengths of each, and reconciling the tensions between the four imperatives mentioned, which pressure both governance and planning in IES decision-making.

Furthermore, participatory processes within the activities of planning institutions are not new in the Mexican context (Guevara, Llado, Uvalle and Navarro, 1994); each institution implements processes of participatory planning consistent with its traditions, cultures and conditions. It is therefore essential to analyze these processes and impacts in a casuistic manner to avoid falling into generalizations that would ignore the concrete context of each IES.

The Autonomous University of Baja California (UABC), is a state public university in Mexico, with about 38,000 students in undergraduate and postgraduate programs. The university, for purposes of the PIFI and other academic aspects, is organized into 11 DES. In it, the activities of planning go back to the beginning of the 1970s; participatory planning has been promoted since the beginning of the 1980s, with achievements, strategies and a variety of results (Gallego, 1984). Recently, we recognized the value of this type of planning for two main reasons: because it promotes the enrichment of the content of the planning products, through the participation of the actors involved, and because participation facilitates the implementation of a plan by those who have collaborated in its formulation.

With these arguments, during the process of formulation of the Plan of Institutional Development (PDI) 2003-2006 (Autonomous University of Baja California, 2003), the administration sought, in accordance with a contextual planning scheme which also emphasizes the aspects of shared leadership and participation (Peterson, 1997), that the academic sector would have an informative function and a participatory role of leadership, in the sense of being partners in the creation of the PDI. This same policy was transferred to the formulation of the PIFI.

The production of the various versions of the PIFI “through a participatory process of strategic planning” has not been entirely foreign to the former traditions of UABC planning. Without an affirmation of the existence of a "total and absolute" participation of the academic community in the formulation of its plans for institutional development, academics and managers already have experienced the production of collaborative works leading to the formulation of institutional documents central to the Plans of Institutional Development.

The formulation of the PIFI in the UABC is carried out based on the collegiate work of the planning teams of the Units of Higher Education (DES), but it is closely directed and supervised by the Department of Planning and Institutional Development (PDIA). It works through teams having detailed knowledge of the educational programs and academic activities of the academic units involved, with first-hand information about the institution’s course and manner of functioning, and with institutional capacity for the making of decisions. It is believed, therefore, that the participatory formulation of the Programs for the Improvement of Units of Higher Education (PRODES) has had favorable conditions for generating projects that meet those needs which have been identified, and that these projects are viable. It is possible that this way of working could help to improve the interior communication of the institution, as well as strengthen collegiate life and establish a culture that values quality and an attitude of continuous improvement. It is also possible that the level of openness with which the proposals were made for the PIFI, as well as their subsequent dissemination, could fortify the policy of transparency and rendering of accounts, improve the corporate identity and provide essential support for the implementation of the PDI 2003-2006 (Autonomous University of Baja California, 2003).

As a result of monitoring these processes in which the PIFI is produced, it might be expected that there would be a reinforcement of certain behaviors, interpretations and perceptions of the institution on the part of the actors involved. The study reported here explores the possible relationship between participation in planning processes and the perception of various institutional aspects by the academics.

I. Method

To answer in an exploratory manner the general question regarding a possible relationship between the participation of academics in institutional planning projects, and their perception of certain dimensions of the institution, we used the information generated in the Annual Survey of Organizational Environment (EAAO) 2006 ( Autonomous University of Baja California, 2007).

The EAAO 2006, like its predecessors, as a general objective, aimed to answer the basic question of how the university community, in this case the academics, perceives the institutional reality from the position in which they participate in it. On a more specific level, information was sought, with which to respond to the previous question, and to consider the work done by the academics themselves, the support service, organizational communication, the administrative service, work conditions, organizational climate, and finally, the teachers’ view on how the directors and officers of the institution are carrying out their duties. There was also an exploration of the levels of identification and subjective affiliation of the academics, together with their institution. The format of the questions used consisted of affirmations about the specific aspects that express different levels of agreement on a Likert scale of five points (DeVellis, 1991).4 The content of the questionnaire was derived from three principal sources:

- Studies of the academics based on surveys (e.g., Gil Anton et al., 1994).

- Questionnaires used by various institutions for the study of their academics (e.g., Selfa et al., 1997).

- Various pertinent aspects in the context of the current PDI (UABC, 2003).

A preliminary version of the instrument used was piloted with a small number of university teachers, and after receiving feedback from the majority of the institution’s officers, the final version of the questionnaire was drawn up.

The EAAO 2006 was applied during April and May of 2006. For each of the institution’s three campuses, there was a list of teachers; this list was not associated with the teachers’ type of contract (full time, part time, or by class), and from it, samples were generated for each campus.

From a universe of 3732 academics of the three campuses, 859 were selected. Trained interviewers were responsible for locating them, explaining the purpose of the survey, telling them explicitly that the survey was voluntary and anonymous, and leaving them a questionnaire to turn in within a couple of days, or at a time specified by the academic.

Using this procedure, the surveys of 443 academics were collected. Of these academics, 190 reported that they were full-time (15.9% of the 1191 full-time academics at the institution).5 The information reported in this paper is solely related to these academics, since they are full-time staff members, a condition which potentially allows them to engage meaningfully in the processes of planning —unlike the situation of part-time personnel and those hired for a limited number of classes. These characteristics made this group of particular interest for our purpose of exploring the relationship between participation and institutional vision.

The information on the questionnaires was collected by the automatic reading of these with a high-speed scanner, after which there was constructed a database which was used with the SPSS program.

II. Analysis of results

The first relevant data for this report has to do with levels of participation in the processes of operational planning related with the PIFI and/or PRODES. As part of the EAAO, 190 full-time academics were surveyed, or 15.9% of a universe of 1191 individuals (UABC, 2007).6 The question was answered by 167 academics, i.e. 87.9% of those surveyed; 41.3% reported that they disagree completely or totally disagree with the statement, “I did significant work on the PIFI and/or the PRODES”; 13.2% expressed a neutral position, and 45.5% expressed agreement or total agreement with the affirmation.

While there are teachers who participate in the process of producing the PIFI and/or PRODES in a systematic way as part of the work groups responsible for them, these groups are necessarily small in relative terms. The highest percentage of academics who say they have participated significantly in these processes may indicate that this participation is a form of work using various modalities, and a good number of teachers perceive that they come into contact with these modalitites. Participation, then, is not limited to a small group of academics, and to that extent, is probably in process of becoming part of the culture.

Given the reported level of participation in planning processes, the question this paper addresses is whether such participation makes a difference in the academics’ perception of the institution. The five options of response to the questionnaire for this report were grouped into three levels: under disagreement were included the levels “Disagree” and “Disagree completely”, the neutral level contained only that, and the level of agreement included “Agree” and “Totally agree.” For each of the three levels having to do with the affirmation regarding participation in the formulation of the PIFI and/or PRODES (disagree, neutral and agree), we obtained the percentages of academics who said they agreed or totally agreed with affirmations selected as relevant to the object of this study.

We will next describe, as regards the institutional level and dependent on the reported level of participation in the formulation of the PIFI and/or PRODES, the responses given by full-time teachers to several statements related to their perception of the institution. These statements have to do with aspects associated with information, work environment, administration and management, decision-making and influence, image and institutional relationship, and satisfaction at work.

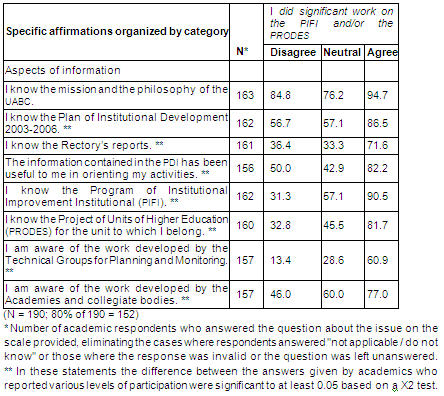

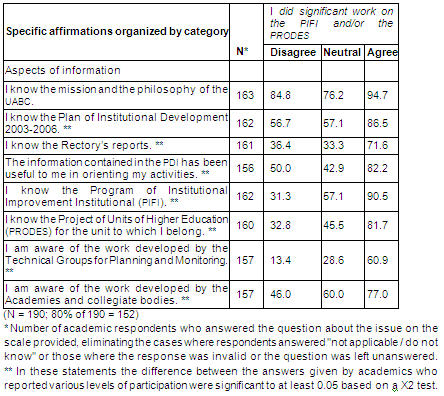

As shown in Table I, those full-time academics who said they played a more significant role in producing the PIFI and/or PRODES, at the same time and in comparison with those academics who claimed non-participation, reported that they were more informed about a number of institutional issues related to activities of planning and collegiate life.

Thus, the percentage of academics who reported participating in these exercises of planning, and who assured us that they know the mission and philosophy of the university, is greater than the proportion of those who reported non-participation (94.7% vs. 84.8%), not in a significant way at 0.05, but at 0.094, on an X2 test (Healey, 1996).

In the same vein, there were greater and significant differences at 0.05 in the context of respective comparisons,7 at different levels of institutional issues, such as being acquainted with the PDI (86.5% vs. 56.7%), being acquainted with the rectory reports (71.6% vs. 36.4%), the perception that the information contained in the PDI has proved useful in guiding their activities (82.2% vs. 50.0%), being acquainted with the PIFI (90.5% vs. 31.3%), being acquainted with the PRODES (81.7% vs. 32.8%), knowing the work of technical groups for planning and follow-up (60.9% vs. 13.4%), and knowing the work done by schools and other collegiate bodies (77% vs. 46.0%).

The above results suggest that participation in the processes of operational planning, such as the PIFI and the PRODES, is associated with the presence or possession of more information regarding processes of overall institutional planning, the processes of operative planning themselves, and at the same time, the activity of various collegiate bodies of the institution. It could be argued then, that the participation reported by the teachers surveyed seems to be associated positively with information on the matters in which they participate.

Table I Percentage of full-time academics surveyed who answered that they were in agreement or totally in agreement with each of the following specific affirmations

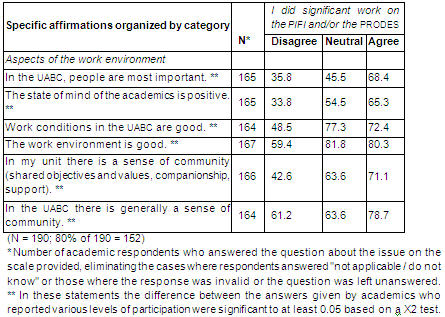

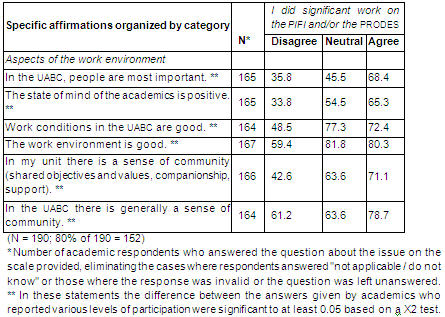

Table II presents the results associated with various aspects of the work environment in which the teachers surveyed develop their activities. In general, the full-time teachers who stated that they participated more meaningfully in the elaboration of the PIFI and/or PRODES, reported a considerably more positive perception and statistical significance of their work environment, than those teachers who said they did not participate. Thus, the percentage of academics who reported participating in the exercises of planning the PIFI and/or PRODES and who believe that people are the most important element at the UABC, is greater than the corresponding percentage of those who reported not having participated (68.4% vs. 35.8%). Differences of the same kind and of similar magnitude are found among teachers who said they had and had not participated in the planning processes regarding other aspects of the work environment, such as viewing the state of mind of the academics as positive (65.3% vs. 33.8%), the conditions of work as good (72.4% vs. 48.5%), and the work environment as good (80.3% vs. 59.4%); furthermore, they considered that in their unit and in the institution in general, there is a sense of community (71.1% vs. 42.6% and 78.7% vs. 61.2%, respectively).

The above results show that the participation of academics in operational planning processes is associated, in comparison with non-participation in such processes, with a more positive perception of their work environment, which includes things ranging from specific work conditions to more subjective aspects, such as a sense of community. In particular, the association between participation and a sense of community could lead to an assertion that these participation processes have been, as well as informative, “responsible” to the extent that they strengthen the concept of a community.

Table II. Percentage of full-time academics surveyed who answered that they were in agreement or totally in agreement with each of the following specific affirmations

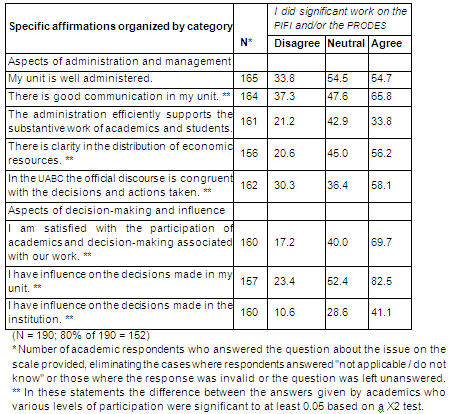

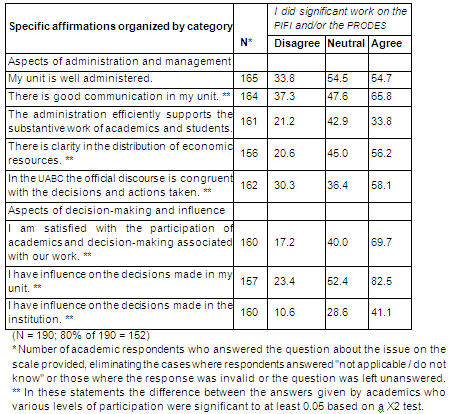

Table III presents the results of the questions associated with university management and administration; included is a set of questions concerning the participation of teachers in decision-making, and their level of influence. Although levels of agreement with the statements relating to institutional administration and management generally do not reflect a view as positive as the levels reported for matters related to being informed and to the work environment, the data show that teachers who reported participating in the production of the PIFI and/or PRODES tend to express a more favorable view of the institution’s administration than do those who reported non-participation.

Thus, the percentage of academics who reported participating in these planning exercises, and who assured us that their academic unit was well run, is higher than the corresponding percentage of those who reported not having participated (54.7% vs. 33.8%), This difference is not statistically significant in the context of the comparison of the respective distributions of response. Differences of the same kind and of similar magnitude were reported also on the perception of academics regarding the presence of a good communication in their unit (65.8% vs. 37.3%; significant), the existence of transparency in the distribution of financial resources (56.2% vs. 20.6%; significant), and the opinion that the official discourse is consistent with the decisions and actions taken (58.1% vs. 30.3%; significant). Notwithstanding the foregoing, the difference becomes less when considering how they perceive the efficiency with which the administration supports the substantive work of academics and students (33.8% vs. 21.2%, not significant), which nonetheless, is low for both groups.

The view of the administration and management is significantly tempered by the level of the community’s reported participation in operational planning processes such as the PIFI and the PRODES. Levels of favorable opinion are not as high as those regarding being kept informed, but the conclusion that it presents a positive relation is maintained.

Table III presents the results of three questions related to academics’ perception of their participation in decision-making, and their level of influence in the environment of their unit and of the institution as a whole. Specifically, a higher percentage of academics who reported a significant participation in the formulation of the PIFI and/or PRODES also said they were more satisfied with the degree of involvement of academics in decisions related to their work, as compared with those who said they had not had this type of participation (69.7% vs. 17.2%; significant).

This difference was also shown in relation to the influence that academics perceive themselves as having in decision-making in the environment of their respective academic units (82.5% vs. 23.4%; significant) and of the university as a whole (41.1% vs. 10.6%; significant).

The results seem to indicate that the participation of academics in the processes of operational planning was seen by them as significant in the sense of feeling that they had an impact on the products generated, although it was significantly lower perceived at the institutional level, as compared with their academic unit. On the other hand, this could be viewed as something natural, since the teachers do in fact participate in the formulation of the PRODES in which their academic units are involved. With these results it is possible to speak of an informed, responsible and significant participation.

Table III. Percentage of full-time academics surveyed who answered that they were in agreement or totally in agreement with each of the following specific affirmations

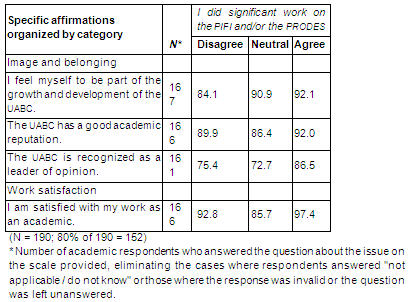

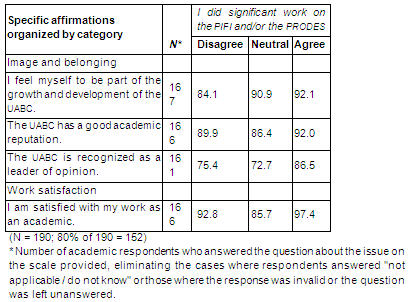

Finally, Table IV presents the results of a group of questions related to the sense of institutional belonging and identity shown by the teachers surveyed, as well as these teachers’ level of job satisfaction in general. In contrast with most of the aspects on which we have previously commented, the views expressed by academics who reported having significantly participated in the planning processes of the PIFI and/or PRODES, and by those who did not report such participation, do not differ greatly, although In all cases the views of the former are more favorable.

Thus, the percentage of academics who said they had participated in these planning exercises, and who assured us that they feel themselves part of the UABC’s growth and development, is greater than the corresponding percentage of those who said they had not participated (92.1% vs. 84.1%; not significant ). A difference of the same kind, but smaller, is given in relation to the perception of the UABC has a good academic reputation (92.0% vs. 89.9%, not significant), but the difference is greater in terms of a perception that the UABC is recognized as a leader of opinion (86.5% vs. 75.4%, not significant). A difference of the same type, but smaller, is given in relation to the perception that the UABC has a good academic reputation (92.0% vs. 89.9%; not significant), but the difference is greater concerning the perception that the UABC is recognized as a leader of opinion (86.5% vs. 75.4%; not significant). Finally, teachers participating in the planning processes of the PIFI and/or PRODES expressed a higher level of satisfaction with their work as academics than non-participants (97.4% vs. 92.8%; not significant); the difference is not great, and both groups reported excellent levels of satisfaction at work.

The previous results suggest that the image and institutional belonging measured by the questions reported, such as general satisfaction at work, do not depend exclusively on the levels of participation maintained by teachers in the institutions. There can be contributory factors capable of having an impact on all the academics, regardless of their level of participation in planning activities. Among these are public recognition and gifts from various agencies that the educational institution and its programs have received in recent years (SEP-ANUIES Prize 2005, SEP-AMEREIAF [Mexican Association of Executives for the Standardization of the Administrative and Financial Information] Prize 2006). Also, perhaps more important is the academics’ degree of involvement in their activities of teaching and research and the level of autonomy in the development of these (Galaz, 2002).

Table IV. Percentage of full-time academics surveyed who answered that they were in agreement or totally in agreement with each of the following specific affirmations

III. Conclusions

Promoting the participation of academic communities in the work of planning the university’s work involves, first, recognizing the value of the experience and knowledge of academics in the various aspects of the institutional dynamic, and that as a result of their participation, the concrete products of planning may have a greater conceptual wealth. As well, it is assumed that the participation of teachers in these processes can promote other, added values, such as the generation of a sense of co-responsibility for the actions outlined in the documents of planning; an increase in the institution’s ability to promote an academic leadership distributed throughout the institution; a greater possibility for implementing the actions contained in a plan of institutional development; and a greater commitment and identity with the institution, its mission and its developmental perspective.

Another consequence could be that the academics might participate in an informed, responsible and meaningful way in the work of planning, monitoring and evaluation, and might improve the academic communities’ perception of the administration and management of their academic units in particular, and of their institution in general.

The analysis in this work shows that in the case of the UABC, the majority of academics who reported having engaged in a process of planning of the importance of the Integral Program of Institutional Improvement (PIFI) and its Program for the Improvement of Units of Higher Education (PRODES), have a more positive perception of the University. More specifically, they are members of the university community who are better informed about the institution’s mission, how the university operates, and about its collegiate life. In addition, these academics have a favorable opinion of their work environment, which includes their work conditions, and they express a greater confidence in the way the university and its academic units are administered, even when dealing with such controversial things as the distribution of financial resources, or the congruence between official discourse and actions taken. In spite of this general appreciation, they do not report a high opinion of the support the administration gives to the work of teachers and students themselves. Finally, they show more influence in the making of decisions at the university, albeit with different nuances depending on the institutional level in question (academic unit versus the university as a whole).

A previous study (Galaz, 2002), showed that the full-time teachers of this university declared themselves to be generally dissatisfied with their participation in decision-making at an institutional level. The results presented here clarify the difference, according to the teacher’s sphere of influence (greater at the unit level than at the level of the university as a whole). This represents an area for improvement, particularly at the institutional level, which should not be ignored by the university’s governance structure, nor by its operation.

On the other hand, the results show that the manifestation of an institutional identity and sense of community, as well as the level of satisfaction at work are not directly associated with the teachers’ participation in the processes of planning. In the particular case of the UABC, such levels are high, and it may be that the margin for improvement cannot permit the possibility of a stronger association.

The effort that an institution of Higher Education must invest in order to facilitate their academics’ processes of participation in exercises of planning is always considerable, particularly when one considers that the time spent, and the ways of carrying out processes such as the PIFI and PRODES become pressure factors for everyone involved. There may be various reasons for academics to participate in this kind of processes (doing their duty, pleasing those in authority, pressures from the former, working under obligation, to obtain resources for personal or group projects, for future interest, etc.). However, the data presented here suggest that these efforts, in addition to helping in the presentation of significantly-funded proposals, may have additional consequences in terms of academics’ perception of their institution and to that extent, such efforts can provide a higher level of "organizational citizenship" in them (Organ, 1990).

Some limitations should be noted concerning the results presented here. Although the sample provided an acceptable margin of error, it is advisable to replicate the study with a larger sample; the information submitted relates to a very specific IES, and therefore, it may be impossible to generalize the results. It is also desirable that this kind of study be complemented by qualitative analysis of the participation of academics in the process of planning: How is it that academics come to be involved in these processes? What is the internal dynamic within the work groups? What authority is exercised by the coordinators of the work groups? What relationships are established between participating and non-participating teachers? What are the conditions necessary for significant participation on the part of the teachers? These are some of the questions it would be appropriate to try to answer, in order to understand the impact which activities of participation in planning have on the teachers and their professional activity within the IES.

Therefore, and based on the information presented, we consider it relevant to favor the presence of spaces for participation, such as those that have always existed in this institution, as well as to enlarge these spaces in an innovative and efficient manner. Thus, this activity can continue under suitable conditions so that the academic work itself may not be undermined, and that it may be secure, having the conditions for generating the results that contribute to the improvement of institutional management. On a broader plane, the results presented could serve as an aid to other institutions of higher education when these institutions are considering processes by which to formulate intermediate-range operational plans like the PIFI and the PRODES, but not limited to them.

References

DeVellis, F. R. (1991). Scale development: Theory and applications. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Galaz, J. F. (2002). La satisfacción en el trabajo de académicos en una universidad pública estatal. Perfiles Educativos, 24 (96), 47-72.

Gallego, M. (1984). La planeación para el desarrollo de la UABC: Objetivos, metas y políticas institucionales, 1984-1987. Mexicali, BC: Universidad Autónoma de Baja California.

Gil Antón, M. (2006). ¿Cómo arreglar un coche? De los indicadores a la calidad, o de la calidad a los indicadores. Foro Nacional sobre Calidad en la Educación Superior. Mexico: Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior-Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

Gil Antón, M., de Garay, A., Grediaga K., R., Pérez Franco, L., Casillas A., M. A., Rondero L., N. (1994). Los rasgos de la diversidad. Un estudio sobre los académicos mexicanos. México: UAM-Azcapotzalco.

Guevara, J. L., Lladó, D. M., Navarro, A., & Uvalle, A. N. (1994, January-March). Desarrollo de un sistema de planeación participativa. Revista de la Educación Superior, 23 (89), 135-144.

Healey, J.F. (1996). Statistics: A tool for the social research. Belmont, CA: Wassworth.

Kent, R. (2005). Recepción de las políticas públicas de educación superior: El PIFI y el PIFOP. Mexico: Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior.

Kent, R., de Vries, W., Didou, S., & Ramírez, R. (1998). El financiamiento público a la educación superior en México: la evaluación de los modelos de asignación financiera en una generación, en tres décadas de políticas de Estado en la Educación Superior. Mexico: Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior.

López, R. & Casillas, M. A. (2005). El PIFI. Notas sobre su diseño e instrumentación. In Á. Díaz & J. Mendoza (Coords.), Educación Superior y Programa Nacional de Educación 2001-2006 (pp. 37-74). Aportes para una discusión. México: Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior.

Morduchowics, A. & Arango A. (2007). Gobernabilidad, gobernanza y educación en Argentina. Buenos Aires: UNESCO-Instituto Internacional de Planeamiento de la Educación.

Navarro, M. A. (2005). El PIFI: Acotar la planeación, acotar el futuro. In Á. Díaz Barriga & J. Mendoza Rojas (Coords.), Educación Superior y Programa Nacional de Educación 2001-2006. Aportes para una discusión (pp.75-90). Mexico: Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior.

Organ, D. W. (1990). The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behavior. In B. W. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 12, pp. 43-72). Greenwhich, CO: JAI Press.

Peterson, M. W. (1997). Using contextual planning to transform institutions. In M. W. Peterson, D. D. Dill, & L. A. Mets (Eds.), Planning and management for a changing environment: A handbook on redesigning postsecondary institutions (pp. 127-157). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Porter, L. (2004). La planeación de la autoridad. La planeación de la libertad. Inconsistencias e incompatibilidades del Programa Integral de Fortalecimiento Institucional (PIFI). Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 9 (22), 585-615.

Rodríguez, R. (2002). Continuidad y cambio en las políticas de educación superior. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 7 (14), 133-154.

Rubio, J. (Coord.) (2006). La mejora de la calidad de las universidades públicas en el periodo 2001-2006. La formulación, desarrollo y actualización de los Programas Integrales de Fortalecimiento Institucional: Un primer recuento de sus impactos. Mexico: Subsecretaría de Educación Superior.

Schuster, J. H., Smith, D. G, Corak, K. A., & Yamada, M. M. (1994). Strategic Govenance. How to make big decisions better. Phoenix: American Council on Education-The Oryx Press.

Secretaría de Educación Pública (2007). Programa Sectorial de Educación 2007-2012. Mexico: Author.

Selfa, L. A. Suter, N., Myers, S., Koch, S., Johnson, R., Zahs, D., Kuhr, B., & Abraham, S. (1997). 1993 National Study of Postsecondary Faculty NSOPF-93: Methodology Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (2003). Plan de Desarrollo Institucional 2003-2006. Mexicali: Author.

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (2007). Encuesta Anual de Ambiente Organizacional 2007 (Cuaderno de Planeación No. 10). Mexicali, BC: Author.

Translator: Lessie Evona York-Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

1The model is conceived as Participative Strategic Planning.

2The Units of Higher Education (DES) are groups of academic units that share disciplinary interests; they may or may not be part of the formal structure of the IES.

3The terms governability and governance are often a cause for confusion. At first, they were linked to the difficulties faced by democracies to deal with growing social demands, to derive later on other issues related to governability but substantially different from it, such as effectiveness. Concern focused on the effectiveness with which the political actors arrived at decisions and on governmental and institutional capacity to implement them. Governability was a systemic attribute, in principle, of the executive branch of government and more broadly, the whole government and the political system as a whole. However, today’s discussion of governability has left behind the concept that the states’ decisions are the principal factor which define legitimacy and effectiveness, to accept the existence of other important influences. There arises then the concept of governance, as the set of institutions, sponsors, structures and game rules which determine and make possible the political and social action. In this way, far from establish a hierarchical structure, the diversity of participants can impede the formulation and implementation of public policies (Morduchowics and Arango, 2007).

4The Annual Survey of Organizational Environment (EAAO) of the Autonomous University of Baja California (UABC) is in reality a set of surveys, closely related with each other, and applied to all university actors (students, academics, officials, administrative personnel and service personnel) yearly since 2004. The details of it can be found in the last of the reports concerned (UABC, 2007).

5For the size of the universe of 1191 full-time academics considered, a sample with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% would be 291 academics. Although the desired sample was not obtained, the sample of 190 has a margin of error, with the same confidence level of about 6.5%.

6Not included in this group are those academics who are presently working in administrative positions. They were considered as officials, and as such were surveyed (UABC, 2007).

7These important differences relate to the distributions of answers given to the questions that are being compared; they are related according to the test used and not to the difference between two particular items of data. The data for certain comparisons are emphasized because they are relevant for this work.

For the size of the universe of 1191 full-time academics considered, a sample with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5% would be 291 academics. Although the desired sample was not obtained, the sample of 190 has a margin of error, with the same confidence level of about 6.5%.

Please cite the source as:

Sevilla, J. J., Galaz, J. F., & Arcos, J. L. (2008). Faculty Participation in Planning Activities and its Telationship with their Vision of the Institution. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 10 (2). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol10no2/contents-sevillagalaz.html