Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 10, Num. 1, 2008

Drop Out or Self-Exclusion? An Analysis of drop out causes in Mexico’s Sonoran High School Students

Elba Abril Valdez

(*)

abril@ciad.mx

Rosario Román Pérez

(*)

rroman@ciad.mx

Ma. José Cubillas Rodríguez

(*)

mjcubillas@ciad.mx

Icela Moreno Celaya

(*)

icela_moreno@hotmail.com

*

Departamento de Desarrollo Humano, Bienestar Social

Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, A. C.

Coordinación de Desarrollo Regional

Carretera a la Victoria Km. 0.6, 83000

Hermosillo, Sonora, México

(Received: June 14, 2007;

accepted for publishing: March 3, 2008)

Abstract

The scholar drop out is not an individual decision. It is conditioned by contextual factors which are identified and analyzed in this research paper among high school students. A survey was applied to 147 high school students to know their family situation, scholar history, reasons why they drop out and their future plans, among other relevant reasons. The results indicated that 86% of the surveyed students abandoned the school between the first and the third semester. Their grade average during the last semester studied was 7.49. The main reasons of the desertion of these students were: economic factors, failure in some subjects, and the lack of interest in their studies. 93% of the participants were not satisfied with the academic level they reached. Nonetheless, they did not plan to resume their studies. The results demonstrated the necessity of an intervention model based on educational policies with higher incentives to add to the school system, flexibility of the transit among subsystems and restructuration of the communication network among the principal actors.

Key words: Secondary education, student attrition, economic factors, student motivation.

Introduction

Dropping out’ is defined as the abandonment of school activities before finishing a grade or academic level (Secretary of Public Education [SEP], 2004.) The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean ([ECLAC] 2003) reports that on the average, about 37% of Latin Americans between the ages of 15 and 19 years leave school during the school year. It also states that most dropping out occurs once junior high school has been completed, and frequently during the first year of senior high school.

In Mexico, there are two types of high school modalities, one known as “baccalaureate” (regular high school, with concentration on academic subjects), and technological education. These are taught in three forms: general baccalaureate, technological and combined. The general baccalaureate accounts for 89.5% of the national student enrollment, and 10.5% for the technological—which shows how little interest most of the youth population have in technological studies. Nevertheless, and in spite of the numbers of students in the modalities, the final efficiency of both is unsatisfactory, since only 57% of the students finish the baccalaureate, and 45% finish technological school. In Sonora, the baccalaureate absorbs 86% of the students enrolled, and the technological modality, 14%.

Of the Sonoran population, 9.85% are between 15 and 19 years old, the age at which students usually go to high school. Of this group, 49.46% are girls (Secretariat of Education and Culture [SEC] 2003). According to the 2000 census, 51.70% of the state’s boys and 40.21% of its girls attend school (National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Informatics [INEGI], 2000). At the high school level, the SEC (2004) reported that during the school year 2002-2003, Sonora had a percentage of school dropouts higher than the national level (17.8%, as compared with 15.9%). These statistics show that an important percentage of the Sonoran youth population are abandoning their studies without providing information about what they are doing once they are outside the school system. Some studies associate the dropout problem with various factors.

1) Economic factors, which include both the lack of resources in the home to pay for the cost of attending school, and the need to work or look for a job.

2) Problems related with the existence or lack of the facilities needed to provide this level of education, which is related with the availability of buildings, their accessibility, and the shortage of teachers.

3) Family problems, mostly mentioned by children and adolescents, related to doing household chores, pregnancy and motherhood.

4) Lack of interest on the part of the young people, as well as parents’ disinterest in having their children continue their studies.

5) Problems of school performance, such as low grades, misconduct and difficulties associated with the age of the students (Merino, 1993; Pina, 1997; Espindola and Leon, 2002; Orozco, 2004).

The foregoing information is confirmed in a study done in Chile, where it was found that the principal causes of school dropouts in young people between the ages of 15 and 19 are their entering the labor market, economic problems, and a lack of motivation. Among the girls, there is also the problem of pregnancy and a dearth of family encouragement to continue studying (Goicovic, 2002). Other studies show that dropping out is linked with the low retention capacity of education systems. This is reflected in high dropout rates in most Latin American countries, and in turn translates into a low number of students with passing grades for the school year (Christenson, Hurley, Evel and Sinclair, 1998; Vera and Ribon, 2000; Jury , 2003; Brewer, 2005).

Similar information was found in a study conducted in Latin America by ECLAC (2003); in seven out of eight countries analyzed, it was noted that the main reason that adolescents drop out has to do with economic factors. Among young women also, economic factors are important, but household chores, pregnancy and motherhood are mentioned most often (ECLAC, 2004).

In Mexico, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the increase in dropping out at the high school level, is associated with a low budget for education, coupled with the residents’ low incomes. The OECD arrived at this conclusion after applying the International Program for the Evaluation of Student Assessment (PISA), in which Mexico placed next to last in Spanish and Mathematics. The document also indicates that both students and schools perform better when the school climate is distinguished by high expectations based on close relationships between teachers and students (OECD, 2004).

In Sonora, there are no follow-up studies for students at this level, so little is known about what they do once they drop out of school. Therefore, information is needed about these high school dropouts, in order to propose actions for improving ultimate efficiency. With the objective of describing this population group, in this paper we show the results of the follow-up studies on young people who dropped out of high school during 2003-2004, in three municipalities in the state of Sonora, Mexico.

I. Methodology

A descriptive study was done, using a random sample representative of adolescents who abandoned their high school studies in the state of Sonora during the school year 2003-2004 in three municipalities.

Participants. A survey was made of a total of 147 students who dropped out in various semesters of in government high schools in the state of Sonora, Mexico, during the academic year 2003-2004. The mean age of inclusion was 15 to 22 years. Taken into consideration was the SEC report for the 2003-2004 school year. This report stated that the dropout level was 16.5%, calculated by using a sample of 350 students for the state, by a simple proportional sampling, with a 95% level of confidence, and a 0.3% margin of error. The study was conducted in the cities of Hermosillo, Nogales and Cajeme, which contain 64% of the state’s enrollment, and which include the state capital, the northern region and the south. The students were randomly selected from rolls provided by the institutions.

Instruments for collecting information. To identify the factors that influence dropping out, a survey was designed for young people. Included were sociodemographic aspects, school history, work history, life plan, expectations, meanings of school space and education.

Procedure. Once the sample of the young people who had dropped out of the various subsystems had been selected, their homes were located and visited for the purpose of applying the instrument, following authorization by the young people and those legally responsible for them (fathers, mothers, or guardians). The data were compiled in a data base and were analyzed with the statistic package SPSS Version 12. A descriptive analysis was made, and measurements of central tendency were obtained. The most significant variables associated with dropping out of high school in the state of Sonora were identified.

II. Results

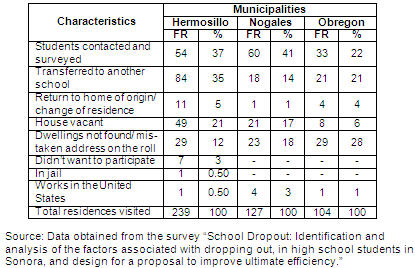

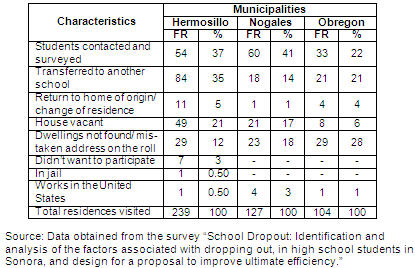

For a sample of 147 students, 470 home visits were made, using addresses furnished by the participating institutions. In 26% (123) of the cases, the young persons had moved to another subsystem or school (Table 1). This is of particular importance with regard to educational policy, since it indicates that a little more than a fourth of the students who dropped out were already registered in another subsystem. Since there is no integrated information system for the various subsystems, nor is there any plan for dealing with equivalencies in the school curriculum, neither the receiving institution nor the one the student has left behind has any information about the individuals who go on with their studies. Based on this situation, there can be seen the need for a method of communication among subsystems, one which would include transferring scholastic records, would permit retrieval of the investment cost in one or two semesters, both for the institution and for the student, and would expedite transition between subsystems.

The sample of students not enrolled in another subsytem was integrated with the study of 147 young people distributed in the cities of Hermosillo (37%), Ciudad Obregon (22%) and Nogales (41%. Table I shows those individuals who returned to another school, where the largest percentage is located in the city of Hermosillo and the lowest in Nogales. Migration to the United States was not observed in the latter city, despite its location, but rather was seen in the first. It is important to note that one of the dropouts from Hermosillo was imprisoned, a consequence that demonstrates the conditions of risk experienced by those who leave school, particularly in the most populated cities, such as this, the Sonora state.

Table I. Home visits in participating municipalities

Characteristics Municipalities

2.1 Sociodemographic profile

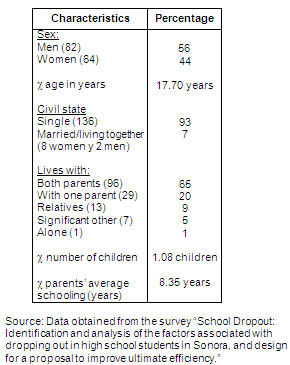

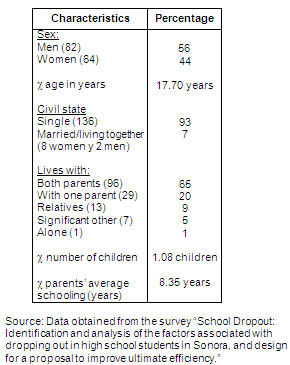

Of the total number interviewed, 44% were girls and 56% were boys, the boys averaging 17.85 years of age (in an age range of from 15 to 22 years), and the girls, 17.55 (in a range of from 15 to 20 years). The majority of those surveyed (93%) said they were single; 65% mentioned that they lived with both parents; 20% lived with just the mother; 9% lived with a relative; and 5% said they were living with a significant other. This last was usually mentioned by girls, which may indicate that young people in this group begin life as a couple at an earlier age. Of male and female students surveyed, 8% said they have children, an average of 1.08 children (Table II), the average number of children for men being 1, and for women, 1.17 (with a maximum of 2).

In this group, 24% of the parents have no significant other; 94% were women, of whom, 54% said they support their families. Even though the majority of the participants reported that they live in a nuclear family composed of parents and children, it is important to point out that a fifth of them live in families having a female head. According to Garcia y De Oliveira (2005), those families headed by women have greater financial difficulties, which can lead to dropping out because of an inability to meet the costs of their children’s education. Some authors, such as Horwitz (1995), mention the effects the lack of a father figure has on the behavior of young people during their adolescence, characterized by an emotional instability which can increase the generation gap, and thus lead to a reduced control over the children’s behavior.

The average schooling for parents was reported as 8.35 years, or less than that achieved by their children as of the date of the survey; this means that these parents failed to complete their junior high school education. While their sons and daughters outdistance them in this area, the level the children reach is too low to give them access to the better-paying jobs that would break the generational cycle of poverty.

Table II. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

On the date of the survey, 38% of the young women and 73% of the young men said they had a job. Among the young men, 50% were working principally as employees in the private sector (salespersons, staff members, etc.) and agricultural workers or day laborers (45%); lesser percentages were mentioned as employees in the public sector (2%) and trade (3%). Of the young women, 71% said they were employed in the private sector (salespersons, staff members, etc.), or day laborers (17%); and lesser percentages were employed as domestic help (4%) or worked in their own businesses (beauty shops) (8%). The majority (86% of the women and 71% of the men) said they worked a day shift. The average weekly salary was $756.19 for men, and $761.50 for women, amounts which, although not statistically significant, show a slight difference in favor of the women. Regarding the work contract, 73% of the men and 100% of the women said it was for an indefinite period. This result is different from that stated by the National Youth Survey, in which the majority of young people reported being hired for a specified period.

2.2 School history of the participant

Some authors report that scholastic history is an important variable that allows us to predict the school dropout rate to some degree (Tinto, 1987). At the time of the survey, 38% of the participants said they had left school in the first semester, 29% in the second, 19% in the third, and the lowest percentages in the fourth, fifth and sixth semesters.

Considering the fact that the admission process is annual, we can see that more than half of the students who enroll, drop out. These results show how important it is to reinforce measures to aid in retaining students during the first year. Moreover, taking into account the high demand in some subsystems, the cost of the admission-dropout process represents not only a restriction of opportunities for those other students who are unable to enter, but also a loss of more than fifty percent of the financial investment.

In contrast, starting with the fourth semester the dropout percentage goes down in proportion, from half of the enrollment in semester one, to only 3% in the last two semesters. This tendency allows us to believe that if students can get through the first, critical period, there is an increased probability of their staying in school and finishing this level of studies. The greater percentage of dropouts during the first semesters also denotes the existence of a high-risk period, which can be traced in scholastic history throughout elementary school or in the first semester of high school. This result is similar to that of a study done by Abril, Roman y Cubillas (2002), in which they interview adolescents who abandoned their studies and also stopped going to school during the first semesters.

The main reasons cited for young men’s leaving school were primarily academic, the failing of subjects (49%), followed by financial considerations (37%), lack of interest (11%), and in smaller percentages, family factors (2%) and the location of the school (1%). In the case of young women, about half cited economic reasons (49%), including the need to work to help their parents, followed by failing subjects (25%), lack of interest (20%), family factors (4%), and school location (2%).

This difference between the sexes with regard to the reasons for dropping out should be studied in depth from a gender standpoint, since there is a cultural assumption that it is men who are the providers, and not women. This change in trends in the Sonoran youth population is desirable in the sense that women take responsibility for their expenses; however, when this responsibility results in their dropping out of school, it also points to a potential loss of the ability to better themselves through higher levels of education. On the other hand, a higher percentage of young women showed a lack of interest in studies, although the differences were not statistically significant (p> .000).

The above would seem to confirm the presence of gender stereotypes in this population, in which stereotypes the inclination toward studies is more masculine than feminine. It is interesting to note, as well, that unlike the results reported in other studies in Latin America, pregnancy or marriage was not a major cause of dropping out among the participants we studied (PRB, 1992; Silver, Giurgiovich and Munist, 1995). In a study done in Sonora with pregnant teenagers, participants reported that they became pregnant some time after leaving school (Roman, 2000). Such a result indicates that there is no direct connection between pregnancy and dropping out; but rather, pregnancy occurs after the dropout, in the absence of alternatives for work and study, so that it becomes a life option for adolescent girls.

Of those who at the time of the survey reported financial reasons as grounds for dropping out, only 66% said they were working, and of these, 34% were female 66%, male. With regard to school performance, 26% of the boys and 47% of the girls said they did not fail any subjects during the last semester completed. In analyzing the reasons for dropping out in this group who had no failed subjects, it was found that the main reason for leaving school had to do with economic problems (68%) and lack of interest (26%). Lesser percentages mentioned the school location (4%) and family reasons (2%). The lack of interest indicates the need to implement programs for motivating students to continue with their studies, especially during the period of highest risk: the first two semesters. Because of this, the relationship between economic hardship and dropout, particularly for girls, who reported fewer failed subjects.

In analyzing failure, we found that the average number of subjects failed during the last school semester was generally 1.96 subjects. When the group was separated by gender, it was observed that there was a greater number of subjects failed by boys ( =2.59) than by girls (

=2.59) than by girls ( =1.55). The reasons cited for failing were learning difficulties, absences, failure to do assignments, and apathy. Learning problems do not arise suddenly, but rather, are part of a process commencing at the time the student begins his/her elementary education. It is at that level that the groundwork is laid for the formation of habits and behaviors which will facilitate later school development (Ortiz and Palafox, 2003). Hence, the importance of analyzing the trajectory of the student body in order to implement actions of prevention and attention, such as the promotion of good study habits, and doing homework, among other things. As for absences, there is a need to revise the educational policy established in the regulations of each school system. The commitment established by the fathers/mothers/guardians and students from the moment they enter the educational system must be explicit and considered as established, in order for the student to be accepted. In addition there should be an analysis made of the desirability of reducing the number of absences allowed per subject, as well as what constitutes acceptable reasons for excused absences.

=1.55). The reasons cited for failing were learning difficulties, absences, failure to do assignments, and apathy. Learning problems do not arise suddenly, but rather, are part of a process commencing at the time the student begins his/her elementary education. It is at that level that the groundwork is laid for the formation of habits and behaviors which will facilitate later school development (Ortiz and Palafox, 2003). Hence, the importance of analyzing the trajectory of the student body in order to implement actions of prevention and attention, such as the promotion of good study habits, and doing homework, among other things. As for absences, there is a need to revise the educational policy established in the regulations of each school system. The commitment established by the fathers/mothers/guardians and students from the moment they enter the educational system must be explicit and considered as established, in order for the student to be accepted. In addition there should be an analysis made of the desirability of reducing the number of absences allowed per subject, as well as what constitutes acceptable reasons for excused absences.

Failing grades continue to be one of the major challenges facing educational systems. Of male and female students who reported having failed subjects, 80% of the males and 60% of the females felt that not passing was related to abandoning their studies. In this group, the average number of failed subjects was higher in males (3.10) than in females (2.91), differences which were not statistically significant.

Another factor identified in the investigation of dropout, was self-esteem and self-confidence: those with good academic performance had a positive view of themselves and of their ability as students. By contrast, students who fail, construct a negative profile of their capabilities and school potential. The attitudes and beliefs that students have about themselves at school, are decisive and powerful as concerning their scholastic success. In this study, most students rated themselves as fair (66%), 31% said they were good students, and 3% said they were bad students.

Of those who perceived themselves as good students, 55% were girls, and 45%, boys; this, coupled with their having the lowest number of failed subjects, confirms the idea that in their case, dropping out is not necessarily associated with a lack of progress, but with economic difficulties. On the average, participants who considered themselves to be good students reported 0.89 failed subjects during the last six months. In contrast, those who considered themselves fair students reported 2.43 failed subjects during the last semester, statistically significant differences (p =. 000. Also, the probability of failing subjects is 7 times greater among participants who perceived themselves as fair (OR = 7.05) than among those who perceived themselves as good students.

On the average, those who perceived themselves as good students reported an average of 3.05 hours spent studying —more than that reported by those who perceived themselves as fair ( = 2.22). More than half of the participants (59%) and 43% of the young men said they were studying enough, and of these, 53% said they had not failed any subjects during the last semester they completed. These data confirm what was expressed concerning the need to provide students with assistance in establishing study habits that will give them more self-assurance for coping with the difficulties inherent in high school work.

= 2.22). More than half of the participants (59%) and 43% of the young men said they were studying enough, and of these, 53% said they had not failed any subjects during the last semester they completed. These data confirm what was expressed concerning the need to provide students with assistance in establishing study habits that will give them more self-assurance for coping with the difficulties inherent in high school work.

Thirty-seven percent of the boys and 52% of the girls consider studying a pleasant activity. This group reported that they devoted an average of 3.13 hours to study—more than the amount reported by those who considered studying to be an activity that people do not like ( = 1.82 pm). Also, the number of subjects failed was higher (

= 1.82 pm). Also, the number of subjects failed was higher ( = 2.62 vs

= 2.62 vs  = 1.14) among those who said they do not like studying. As for the average grade recorded, this was very similar in both cases: 7.68 for those who said they enjoyed studying, and 7.31 for those who said they did not.

= 1.14) among those who said they do not like studying. As for the average grade recorded, this was very similar in both cases: 7.68 for those who said they enjoyed studying, and 7.31 for those who said they did not.

2.3 Dropout and employment

Adolescence is associated with preparing to enter into adult activities, and with the privilege of belonging to the educational system as the primary social obligation. The school environment provides not only the abilities needed for a future entrance into the labor market, but also provides activities which constitute training for that entrance.

Seventy percent of the females and 82% of the males mentioned having worked at some time. The average age for the boys’ first job was 16.15 years, and for the girls’, 15.93 years. These data are consistent with those reported in the 2005 National Youth Survey, in which the average age, nationally, for the first job was 16 years. At the time of the survey, 58% of the participants said they were working, and of these, 38% were female and 73%, male.

The number of subjects failed, for those who said they had once worked, was lower than for those who reported not having worked ( =

=  = 1.87 vs. 2.97). These results are similar to those found in a study conducted with high school students in Sonora, where boys reported a higher number of failed subjects. However, the percentage was lower among those who said they had a job; this could be related to the sense of responsibility that having a job implies (Roman, and Cubillas April, 2000). The reasons those who were working gave for not continuing with their studies were mainly economic (49%) and academic (38%). Smaller percentages cited the location of the school (12%) and family reasons (1%).

= 1.87 vs. 2.97). These results are similar to those found in a study conducted with high school students in Sonora, where boys reported a higher number of failed subjects. However, the percentage was lower among those who said they had a job; this could be related to the sense of responsibility that having a job implies (Roman, and Cubillas April, 2000). The reasons those who were working gave for not continuing with their studies were mainly economic (49%) and academic (38%). Smaller percentages cited the location of the school (12%) and family reasons (1%).

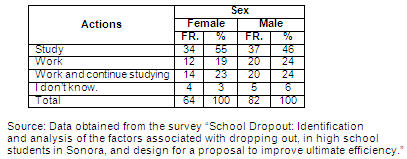

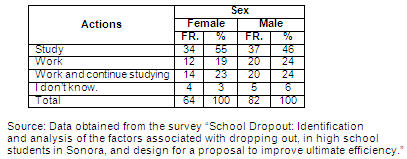

Of those who said they were working, 61% mentioned being satisfied with their current job; 65% of the participants felt that their work does give them the opportunity to continue studying. In relation to the question about what they could do to improve their economic status, 46% of the boys and 55% of the girls said they should study (Table III).

Table III. Actions to improve economic status, according to sex

At the time of the survey, 93% of the participants (of whom 46% were female and 54% were male) were not satisfied with their level of educational achievement. Of these, 98% mentioned that they would like to continue with their studies to learn more things, get a better job, have a better life and earn more money—but none had planned to resume their studies or looked into any possible options regarding schools. Similarly, despite their dissatisfaction with their level of educational achievement, 43% of the participants had neither any employment nor any other occupation, which speaks to us of a significant percentage of unemployed youth. Such a result shows their lack of a life plan, and/or short to medium-range goals related to their education.

Palomar and Marquez (1999) point out that dropping out of school during this period may be related to the adolescent’s lack of goals and/or a life plan, as well as problems in family relations. On the other hand, the International Labor Office (ILO) (2005), reports that those young people who are neither employed nor in school are more likely to have behavior which puts their health and that of others at risk, whether by criminal conduct or early pregnancies. Similarly, it shows that the patterns of behavior and attitudes established at an early age persist throughout life. Thus, young people who have long periods without work or study tend to be employed for less time and to receive lower wages in their adult years.

III. Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, one can conclude that male and female students who drop out usually do so during the first semesters of high school. The problem is observed more among young men, although the gender difference is not significant. The average age for dropping out in both sexes was 17 years. Most of these young people have parents with less schooling than their children. Among this group’s main reasons for dropping out are economic factors in the case of girls, and in that of boys, failing subjects.

These are young people who consider their performance in school as mediocre, and who have no commitment or future plans, since even though most of them are not satisfied with the level of educational they have achieved, they have no concrete plans for continuing with their studies, but only good intentions. The problem of dropping out is multifactorial, and the data from the state of Sonora is confirmed. However, unlike other studies which show girls dropping out of school mainly because of pregnancy, in this case pregnancy was not one of the principal causes.

In general, the reasons found for school dropouts in this study were economic ones; these included both a lack of resources in the home with which to pay for the costs incurred by school attendance, and also the need to work or to seek employment. They also include family problems, those associated with a lack of interest, including the virtual, unreal valuation that fathers and mothers make regarding education; and the problems of school performance: poor performance, behavioral problems and others associated with the students’ age.

Today, education offers teenagers and young people different experiences that help define their life plan, besides being an indispensable factor for training in social skills and personal development. Thus, young men and women who drop out are disadvantaged in adjusting to the changes imposed by society. They are also disadvantaged with regard to employment, because of their lack of training. Dropping out of school accentuates the difficulty of breaking the cycle of poverty and lack of social mobility (Goicovic, 2002; Suarez and Zarate, 1999; Beyer, 1998).

Now, those who do not have at least 12 years of schooling and a high school diploma have little chance of entering the job market or of obtaining quality jobs that will enable them to improve their living conditions or situation of poverty. In turn, the dropouts are more likely to engage in exclusionary dynamics which may endanger their physical and emotional wholeness. Similarly, dropping out impoverishes the cultural capital that is subsequently transmitted to their children, so that social and educational inequality is reproduced, one generation after another (Goicovic, 2002; Beyer, 1998; War, 2000).

Reversing the school dropout process involves, first, capturing young people’s interests, demands and forms of social intervention, and trying to make the youth culture an integral part of the school culture. This implies, among other things, developing teaching and learning processes that line up with reality and with the interests of young people. It also includes enlarging the spaces and their mechanisms of institutional participation.

References

Abril, E., Román, R., & Cubillas, M. J. (2002). Educación y empleo en jóvenes sonorenses. In E. Ramos, E. Carlos & L. Galván (Comps.), Investigación educativa en Sonora (pp. 229-242). Hermosillo: Red de Investigación Educativa en Sonora A.C.

Beyer, H. (1998). ¿Desempleo juvenil o un problema de deserción escolar? Estudios Públicos, 71, 89-119.

Brewer, L. (2005). Jóvenes en situación de riesgo: La función del desarrollo de calificaciones como vía para facilitar la incorporación al mundo del trabajo. (Work document No. 19). Ginebra: Oficina Internacional del Trabajo.

Christenson S., Hurley Ch., Evelo D., & Sinclair M. (1998). Dropout prevention for youth with disabilities: Efficacy of a sustained school engagement procedure. Exceptional Children, 651 (1), 7-21.

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. (2003). Elevadas tasas de deserción escolar en América Latina. In CEPAL, Panorama Social de América Latina 2001-2002. Retrieved December 16, 2004, from: http://www.eclac.cl

Espíndola, E. & León, A. (2002). La deserción escolar en América: Un tema prioritario para la agenda regional. Revista Iberoamericana de educación, 30. Retrieved November 15, 2004, from: http://www.rieoei.org/rie30a02.htm

García, B. & De Oliveira O. (2005). Mujeres jefas de hogar y su dinámica familiar. Papeles de Población, 43, 29-51.

Goicovic, I. (2002). Educación, deserción escolar e integración laboral juvenil. Última Década, 16, 11-53.

Guerra, M. (2000). ¿Qué significa estudiar el bachillerato? La perspectiva de los jóvenes en diferentes contextos socioculturales. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 5 (10), 243-272

Horwitz, N. (1995). La socialización del adolescente y el joven: el papel de la familia. In M. Maddaleno, M. Munist, C. Serrano, T. Silver, E. Suárez, & J. Yunes (Comps.), La salud del adolescente y el joven (Scientific Publication No. 554, pp. 112-118). Washington, DC: Organización Panamericana de la Salud

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. (2000). XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda. Tabulados Básicos. Tomo II. Mexico: Author.

Jurado, J. (2003). Problemáticas socioeducativas de la infancia y la juventud contemporánea. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 31, 171-186.

Merino, C. (1993). Identidad y plan de vida en la adolescencia media y tardía. Perfiles Educativos, 60, 44-48.

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económico. (2004). Problem solving for tomorrow’s world. First measures of cross-curricular competencies from PISA 2003. Retrieved November 15, 2004, from: http://oberon.sourceoecd.org/vl=1196316/cl=22/nw=1/rpsv/ij/oecdthemes/

99980029/v2004n22/s1/p1l

Orozco, C. (2004). Deserción escolar, un problema que se acentúa. Vanguardia. Retrieved November 18, 2005, from: http://vanguardia.com.mx

Ortiz, I. & Palafox, E. (2003). Problemas de los estudiantes con relación a su ingreso, trayectoria escolar y egreso. Paper presented at Seminarios de Diagnóstico Locales. Comisión Especial para el Congreso Universitario, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Retrieved February 25, 2007 from: http://www.cecu.unam.mx/ponsemloc/ponencias/1127.html

Palomar, J. & Márquez, A. (1999). Relación entre la escolaridad y la percepción del funcionamiento familiar. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 4 (8), 299-343.

Piña, J. (1997). La eficiencia terminal y su relación con la vida académica. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 2 (3), pp. 85-102.

Román, R. (2000). Del primer vals al primer bebé: Vivencias del embarazo en las jóvenes. Mexico: Instituto Mexicano de la Juventud-Secretaría de Educación Pública.

Román, R., Abril, E., & Cubillas, M. (2000). Diagnóstico psicosocial de estudiantes del nivel medio superior en el estado de Sonora (Technical report for El Colegio de Bachilleres). Hermosillo, Sonora: Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, A.C.

Secretaría de Educación Pública (2004). Sistema educativo de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Principales cifras. Ciclo escolar 2003-2004. Mexico: Author.

Secretaría de Educación y Cultura (2004). Estadísticas básicas del sistema educativo del estado de Sonora. Inicio de cursos 2003-2004. Hermosillo: Gobierno del Estado de Sonora.

Silver, T., Giurgiovich, A., & Munist, M. (1995). El embarazo en la adolescencia. In M. Maddaleno, M. Munist, C. Serrano, T. Silber, E. Suárez, & J. Yunes, J. (Comps), La salud del adolescente y el joven (Scientific Publication No. 552, pp. 252-263). Washington, DC: Organización Panamericana de la Salud.

Suárez, M. & Zaráte, R. (1999). Efecto de la crisis sobre la relación entre la escolaridad y el empleo en México: de los valores a los precios. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 2 (4), 223-253.

Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Vera, J. & Ribón, M. (2000). Éxito, fracaso y abandono escolar en la educación secundaria. Análisis de la primera cohorte que culmina el ESO en el municipio de Puerto Real. Retrieved November 18, 2005, from: http://www.ase.es/comunicaciones/vera_borja.doc

Translator: Lessie Evona York-Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

Please cite the source as:

Valdez, E. A., Román, R., Cubillas, M. J., & Moreno, I. (2008). Dropout or Self-Exclusion? An Analysis of Dropout Causes in Mexico’s Sonoran High School Students. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 10 (1). Retrieved month, day, year from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol10/no1/contents-valdez.html

![]() =2.59) than by girls (

=2.59) than by girls (![]() =1.55). The reasons cited for failing were learning difficulties, absences, failure to do assignments, and apathy. Learning problems do not arise suddenly, but rather, are part of a process commencing at the time the student begins his/her elementary education. It is at that level that the groundwork is laid for the formation of habits and behaviors which will facilitate later school development (Ortiz and Palafox, 2003). Hence, the importance of analyzing the trajectory of the student body in order to implement actions of prevention and attention, such as the promotion of good study habits, and doing homework, among other things. As for absences, there is a need to revise the educational policy established in the regulations of each school system. The commitment established by the fathers/mothers/guardians and students from the moment they enter the educational system must be explicit and considered as established, in order for the student to be accepted. In addition there should be an analysis made of the desirability of reducing the number of absences allowed per subject, as well as what constitutes acceptable reasons for excused absences.

=1.55). The reasons cited for failing were learning difficulties, absences, failure to do assignments, and apathy. Learning problems do not arise suddenly, but rather, are part of a process commencing at the time the student begins his/her elementary education. It is at that level that the groundwork is laid for the formation of habits and behaviors which will facilitate later school development (Ortiz and Palafox, 2003). Hence, the importance of analyzing the trajectory of the student body in order to implement actions of prevention and attention, such as the promotion of good study habits, and doing homework, among other things. As for absences, there is a need to revise the educational policy established in the regulations of each school system. The commitment established by the fathers/mothers/guardians and students from the moment they enter the educational system must be explicit and considered as established, in order for the student to be accepted. In addition there should be an analysis made of the desirability of reducing the number of absences allowed per subject, as well as what constitutes acceptable reasons for excused absences.![]() = 2.22). More than half of the participants (59%) and 43% of the young men said they were studying enough, and of these, 53% said they had not failed any subjects during the last semester they completed. These data confirm what was expressed concerning the need to provide students with assistance in establishing study habits that will give them more self-assurance for coping with the difficulties inherent in high school work.

= 2.22). More than half of the participants (59%) and 43% of the young men said they were studying enough, and of these, 53% said they had not failed any subjects during the last semester they completed. These data confirm what was expressed concerning the need to provide students with assistance in establishing study habits that will give them more self-assurance for coping with the difficulties inherent in high school work. ![]() = 1.82 pm). Also, the number of subjects failed was higher (

= 1.82 pm). Also, the number of subjects failed was higher (![]() = 2.62 vs

= 2.62 vs ![]() = 1.14) among those who said they do not like studying. As for the average grade recorded, this was very similar in both cases: 7.68 for those who said they enjoyed studying, and 7.31 for those who said they did not.

= 1.14) among those who said they do not like studying. As for the average grade recorded, this was very similar in both cases: 7.68 for those who said they enjoyed studying, and 7.31 for those who said they did not.![]() =

= ![]() = 1.87 vs. 2.97). These results are similar to those found in a study conducted with high school students in Sonora, where boys reported a higher number of failed subjects. However, the percentage was lower among those who said they had a job; this could be related to the sense of responsibility that having a job implies (Roman, and Cubillas April, 2000). The reasons those who were working gave for not continuing with their studies were mainly economic (49%) and academic (38%). Smaller percentages cited the location of the school (12%) and family reasons (1%).

= 1.87 vs. 2.97). These results are similar to those found in a study conducted with high school students in Sonora, where boys reported a higher number of failed subjects. However, the percentage was lower among those who said they had a job; this could be related to the sense of responsibility that having a job implies (Roman, and Cubillas April, 2000). The reasons those who were working gave for not continuing with their studies were mainly economic (49%) and academic (38%). Smaller percentages cited the location of the school (12%) and family reasons (1%).