Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 9, Num. 2, 2007

Opinions of Students Enrolled in an Andalusian Bilingual

Program on Bilingualism and the Program Itself

Francisco Ramos Calvo

framos@lmu.edu

School of Education

Loyola Marymount University

1 LMU Drive suite 2649

90045

Los Angeles, CA, USA

(Received: March 29, 2007;

accepted for publishing: August 31, 2007)

Abstract

The Regional Ministry of Education of the Autonomous Government of Andalusia, an autonomous community in the South of Spain, has established several bilingual programs to improve language proficiency of its student population. The programs, which undertake second languages as vehicular languages at the classroom, encourage student’s bilingualism, academic development and positive attitudes toward other groups. The following paper examines opinions given by a group of students enrolled in an Andalusian bilingual program about those matters. Students had different positive opinions on bilingualism as well as the program in general; however, they had some doubts over the intellectual and cognitive benefits of learning languages.

Key words: Bilingual education programs, bilingualism, teaching methods.

Introduction

Two- way bilingual programs are an innovative way to encourage students to learn a second language at school by undertaking it as a vehicular language of instruction and communication, instead of learning it like it used to be on traditional programs, where languages were considered separate courses. As a result, students are provided with authenticity and, as an added benefit to it, using a second language contributes to improve their academic and linguistic knowledge about it.

Some Autonomous Bilingual Spanish Communities, like the Basque Country, established that kind of teaching model to encourage Euskera learning (the regional language) together with Spanish and English two decades ago through an interesting trilingual educational model (Lasagabaster, 2001; Ruiz de Zarobe, 2005; Torres-Guzmán and Etxeberría, 2005). However, the rest of Spain had to wait until 1996 when a collaboration agreement was signed between the Ministry of Education and the British Council, so that a joint integrated curriculum which considered English as a vehicular language could be implemented at various infant and primary education centers in several Autonomous Communities (Ramos, 2006). The success of it among the different social strata at several school communities increased progressively not only the number of centers involved but also their geographic extent, and, at the same time, it lead several Regional Ministries of Education in the Autonomous Communities that hadn’t established bilingual programs to adopt similar models to facilitate their students’ language learning.

That was the case of Andalusia, whose Regional Ministry of Education established four bilingual sections of German and French at several schools in two of its provinces in 1998. The popular demand for these centers made sections spread widely and led the Regional Ministry to pass on the Plurilingualism Promotion Plan which settled the framework for the bilingual programs’ implementation and expansion to all the provinces of the Community (Gabinete de Prensa, 2005). The following paper explains briefly the beginning, objectives, and benefits of two- way bilingual programs. Likewise, it analyzes the opinions of a group of Andalusian students on bilingualism, and the bilingual program they were enrolled in.

I. The beginning and goals of two-way bilingual programs

The beginning of Two- way bilingual programs goes back to the early 1960’s. A great number of Cuban students arrived at Miami schools since their parents were escaping from Castro’s dictatorship, this fact made educational authorities of Miami-Dade County to decide on establishing a new bilingual program, which was sponsored by the Ford Foundation, at the Coral Way Elementary School.

In that program, Spanish and English -speaking students were segregated by their first language and they received linguistic and academic instruction in English and Spanish; they received it in their first language during the first half of the day and in the second language, during the second half. The program was then modified and improved to fulfill specific needs of other District schools. Its main objective was teaching English as well as American culture to foreign students who had just arrived; however, at the same time, it prevented students from forgetting their own language and culture (Beebe and Mackey, 1990). As the program spread to other Sates, it was modified and its goals were redefined. Nowadays, it has four major goals: the same academic standards and curriculum for other students will be maintained for bilingual programs; students will develop high levels of proficiency in the second language and attain academic achievement; students will develop positive attitudes and behaviors toward other cultures and themselves (Howard, Sugarman, and Christian, 2003).

In order to achieve those goals, bilingual programs provide instruction in classrooms where the number of minority and majority language speaking -students remains almost the same if not equal, so that everyone can interact within the linguistic models, and students speaking one language can help the others. (Howard et al., 2003). The time of instruction in each language depends on the model that has been settled; the most common ones are the 90/10 and the 50/50 models, they are named after the percentage of time of instruction provided in the minority or majority language. For instance, in the model referred to as 90/10, students receive 90% of instruction in the minority language (usually Spanish) and 10% in the majority language during the first grade levels of education. Over the course of grades, these ratios change gradually until they reach balance by third grade. In a 50/50 model, students are instructed equally in both languages at all levels (Howard et al., 2003).

Usually, students have a pair of teachers, one for each course (different in content and language). During class, teachers speak only one language in order to prevent students from using both languages indistinctively or trying to use their first language when they find it difficult to express themselves in the second language. As a rule, teachers share groups and switch at midday. It makes teachers’ job easier, since they teach the same content twice a day and it benefits students since they receive instruction in both languages everyday (Freeman and Freeman, 2005).

As far the Andalusian programs are concerned, they started in the mid 1990’s in order to face up the social demand for instruction in a second language from students of the public community system. The response of the Ministry of Education of the Andalusian Autonomous Government to this issue was the agreement signed by the Alliance Française and the Goethe-Institute by which German and French bilingual sections were established at four schools in two provinces of the territory. Thanks to the support of those countries’ consulates, sections spread out to other schools and consequently the Ministry had to institutionalize and start the program in every Community province by approving the Plurilingualism Promotion Plan in 2004 (Consejo Asesor para la Segunda Modernización de Andalucía, 2003).

The main objectives of that plan were to develop plurinlingual and pluricultural skills, to sequence the contents of each stage of schooling and to adapt assessment criteria to those established in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, and Assessment (Consejería de Educación, 2005). Specific objectives included: To teach and learn certain areas of knowledge in at least two languages, to develop a better understanding about other cultures, and a greater cognitive flexibility. In order to achieve those objectives, second languages were used as vehicular languages during academic discussions and presentations (García, 2005) integrating student’s knowledge, experience, and opinions (Cummins, 1996); these premises were an accurate reflection of the American program approach.

The lack of native foreign-language speakers at school did not allow the presence of students speaking two different languages in the classroom, as it did happen in the United States. It was solved by increasing progressively the number of hours of instruction in a second language. For instance, an hour and a half given every day during the week in first grade changed gradually until it reached seven hours in the fifth and sixth grades (Dirección General de Ordenación y Evaluación Educativa, 2005), those classes were given by teachers who were subject and language specialists. Currently, there are 250 bilingual centers. English is taught in 206, French in 36, and German in 8; though, forecasts say that 400 bilingual centers will exist by 2008, the last year of the community’s legislature (Gabinete de Prensa, 2005).

II. Bilingual program benefits

In the United Sates, bilingual program students showed significant progress in math, reading and writing as well as proficiency in both languages (Alanis, 2000; Cazabon, Lambert and Hall, 1993; Howard, Christian and Genesee, 2003); furthermore, they improved creativity and cognitive flexibility more than students did in traditional programs (Cummins, 1991). The results made parents, teachers and students, who play a crucial role for the program success, to support it unquestionably, (Lindholm-Leary, 2001; Shannon and Milian, 2002). The surveys carried out among the students showed most of them had positive opinions on the program (Lindholm-Leary, 2001), other ethnic group members, plurilingualism and multiculturalism, in general (Cazabon, Lambert and Hall, 1993). Similar results were obtained from Spanish students enrolled at schools with similar educational models (Blas Arroyo, 2002; Huguet and Llurda, 2001; Lasagabaster, 2001; Torres-Guzmán and Etxeberría, 2005).

In Andalusia, and due to the recent program implementation, there is little information on this regard. Except for surveys done at some schools; however, the results haven’t been published yet. As a result, the objective of this paper is to open new ways for research and to get to know students’ opinions on Andalusian bilingual programs and bilingualism as well. The second objective is to facilitate data to the School Management Team at the school were this project was carried out in order to examine positive aspects on the program, but especially those that can be improved by students.

III. Methodology

In order to carry out this research, the author looked for one of the persons in charge of bilingual programs in Andalusia, who gave him the names from several schools interested in knowing their student attitudes toward the program components and principles where they were enrolled in. After selecting one of them, the author contacted the head teacher, who authorized carrying out the research once objectives and characteristics of the questionnaires to be answered by the students were explained to her in a private meeting. The head teacher joined the researcher, and then they went to the classrooms that were chosen in order to explain teachers and students the objectives of the research.

3.1 Participants

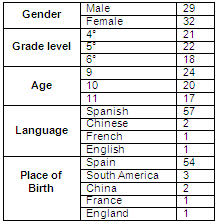

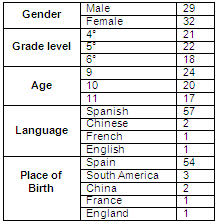

The school where the research was carried out was one of the first schools where a French- Spanish bilingual program was settled for the 1998-1999 calendar; it is located in a neighborhood in Seville, the capital city of Andalusia. It was chosen for the project because of the willing and interest shown by the School Management Team to know student’s opinions. The program worked in one classroom per course so there were only 114 students enrolled in it, out of the 417 enrolled in pre-school and elementary education. The head teacher as well as the researcher decided to leave students under the fourth grade out of the project because they hadn’t been exposed enough to the second language so as to make value judgments about their learning so the validity of their answers could have been affected because of the difficulty to answer the questions. Consequently, only fourth, fifth and sixth grade students were taken into consideration. The number of girls was a little bit higher than the number of boys; most of the children were born in Spain and almost of all them spoke Spanish as their first language though some of them spoke Euskera, since they were from the Basque Country. The following table summarizes the obtained information.

Table I. Participant’s Description

3.2 Instruments and procedures

The questionnaire applied for the research was a version of the one created by Lindholm-Leary (2001) for one of the most complete research works carried out in the United States to study parents, teachers and students attitudes toward bilingualism and bilingual programs. It was divided into two sections. The first one consisted of five questions designed to gather information about grade, age, gender, first language, and place of birth; the second one consisted of 13 items divided into three main categories: interpersonal relationships, bilingualism benefits, and program satisfaction. The reliability of categories was respectively 0’72, 0’73, and 0’ 62 in the original research (Lindholm-Leary, 2001). The level of agreement of the participants was measured through a five-level Likert scale ranging from option 1 “strongly disagree” to option 5 “strongly agree”, and option 3 “neither agree nor disagree”, as a mid option. Then, answers were classified into three main categories in order to make easier the result analysis into “agree/ strongly agree”, “neither agree nor disagree” and “disagree/strongly disagree”.

The questionnaire was completed in the classroom. The researcher read at loud every item to the 4th and 5th grade students to ensure their comprehension, while students from the 6th grade didn’t need any help. They took 20 minutes approximately to answer it. The results were analyzed with SPSS 13.0 aid and contingency tables were elaborated for variables “age” and “grade”, “gender” and “grade level”, as well as “age” and “gender” to observe responses in detail. The limited sample size did not allow doing more complex statistical analysis; therefore, the results are presented by indicating the number of students who responded, as well as the percentage this number represents out of the total number.

IV. Results

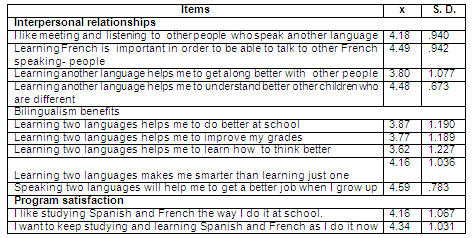

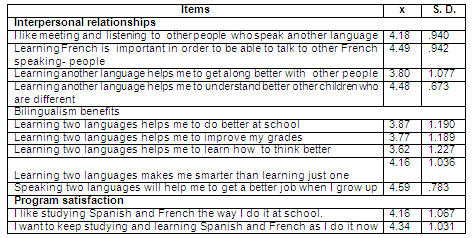

As it can be observed in Table II, students agreed on the way the school delivered a second language and they expressed they wanted to continue receiving bilingual instruction. Likewise, they considered several benefits about learning a second language, like the ability to meet, talk to and comprehend other people better, as well as the possibility of getting better jobs in the future. However, they recognized less some intellectual and cognitive benefits of bilingualism.

Table II. Measurements and Standard Deviations of the responses

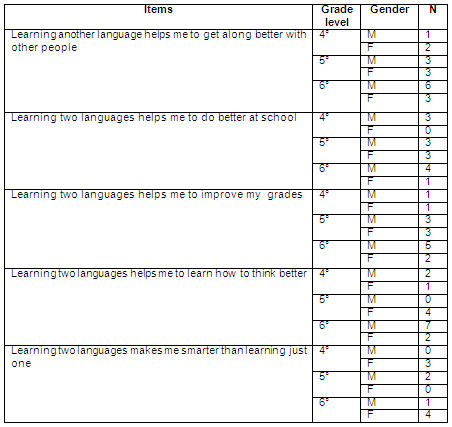

Table III gives a detailed analysis of student responses. It shows that the majority of the students appreciated the positive impact of a second language on interpersonal relationships, intellectual capacity and getting a better job in the future. Regarding the bilingual program itself, more than 80% of the students had a good opinion on it and wanted to continue receiving instruction in the same way. However, two facts are worth mentioning, and they are the relative high percentages of individuals who had doubts or who disagreed about some of the intellectual benefits of bilingualism. About 25% of the students didn’t know whether bilingualism helped them to do better at school, to think better or to get better grades; more than 16% of them doubted it influenced their intellectual capacities and almost 30% of them weren’t sure if bilingual education supported interpersonal relationships. Furthermore, about 10% of the students disagreed about the fact that learning a second language helps them to do better at school, to get better grades or to think better.

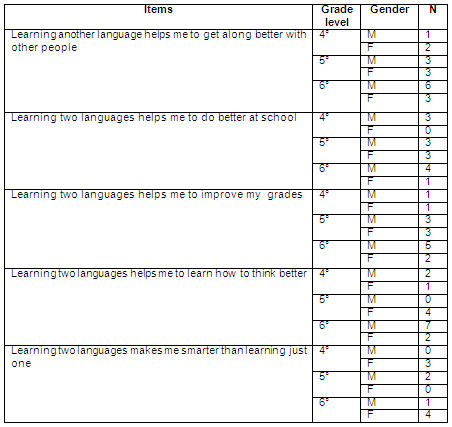

Table III. Questionnaire Responses

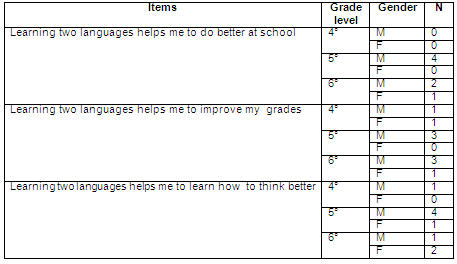

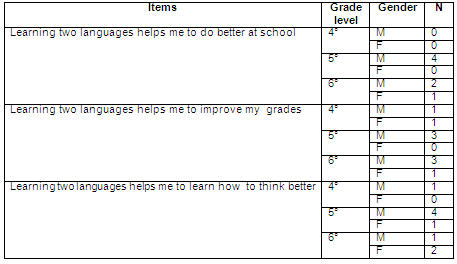

Tables IV and VI analyze individuals who answered whether “neither agree nor disagree” or “disagree/strongly disagree” by gender and grade level. It can be seen that sixth grade students doubted the most about the effect of bilingualism on interpersonal relationships. Also, they were the ones who doubted the most about the academic benefits of bilingualism and the effect of it on their grades. Curiously, more boys than girls of this group didn’t know whether bilingualism would help them to improve interpersonal relationships, academic achievement, way of thinking, or grades, while more girls answered they didn’t know if it would make them smarter. Most of the participants who disagreed with intellectual benefits of bilingualism were on the fifth grade.

Table IV. Analysis of responses “neither agree nor disagree”

Table V. Students who disagreed

V. Discussion

Percentages appearing in the presentation of results may be confusing since every answer worths significantly because of the limited number of respondents. For that reason, the number of students always appears next to the percentage. In spite of the precaution that should be taken when examining results, they clearly show participant’s opinions and allow the School Management Team to analyze the numbers in detail after the research is done.

Keeping in mind this limitation, it can be observed that answers of students showed, in general, positive opinions on bilingualism and the program they attended to. For instance, Most of students appreciated the benefit of learning two languages as well as meeting and understanding better other people who speak a different language; a high number of students also considered that being bilingual would help them to improve their relationships with other francophone’s people, as well as it would help them to get a better job in the future. These answers, which are similar to those of other studies (Blas Arroyo, 2002; Howard, Christian and Genesee, 2003), confirmed the achievement of objectives.

Nevertheless, the number of students who expressed doubt or disagreement about some items cannot be overlooked. Results, fluctuating from 34.5% of those students who didn’t know if learning two languages would help them to do better at school to the 42.6% of those who didn’t know if learning two languages would help them to learn how to think better, may be surprising because they derive from the direct beneficiaries of the program. As a result, it is convenient to take into account some considerations.

- The statements in some items might have influenced negatively on some responses. For example, one out of the four items related to interpersonal relationships: “Learning another language helps me to get along better with other people” was the least supported. It might have been written differently referring specifically to “other people who speak French”. In that way, it might have been more supported by identifying clearly who the people were. However, it is important to point out the fact that more than 80% of the respondents had a positive opinion on French as a vehicular language of communication, which is a relevant piece of information when considering that its use is limited in and out of school due to the monolingualism that prevails in the city. Under these circumstances, it wouldn’t have been strange to observe some items being less supported by students, because the limited access to francophone’s people prevents them from testing the veracity of content.

- The fact that most of doubts and negative answers were submitted by fifth and sixth grade students can result from the fact that the higher grade level they reach, the more difficult content in the second language become, so they need greater proficiency to obtain good results, as it has been mentioned before in other research papers (Valdés, Fishman, Chávez and Pérez, 2006). That can have an impact on the negative attitudes showed by some students, because they consider they have to make a greater effort to obtain the same grades than that of their peers enrolled in traditional programs where courses are given in their first language. In this regard, the fact that most of participants who expressed doubt or disagreement about the benefits of bilingualism were boys, it might be a mere coincidence; however, it is a piece of information to be considered by the School Management Team.

- The lack of specific explanations to parents and students by the School Management Team on bilingualism, in general, the benefits from the phenomenon, similarities among language acquisition processes or advantages resulting from the common underlying competence in every language (Cummins, 1991) might have affected the high number of participants who expressed their doubts about the impact of bilingualism on intelligence. By including these kind of explanations in the program orientation meetings, students could understand better the importance of second languages as vehicular languages of communication as well as the intellectual and cognitive benefits resulting from these learning processes (Bialystok, Craik, and Freedman, 2007).

VI. Conclusion and implications

The purpose of this research paper was to examine opinions given by a group of students enrolled in an Andalusian bilingual program on bilingualism and bilingual programs. During first stage, analysis of the results allowed to observe that the majority of students appreciated the benefits of learning a second language and they expressed they were satisfied with the instruction received in the program, though, a percentage of them expressed doubt. According to the obtained results, three are the main areas that the School Management Team should consider for further research:

- Negative answers concentrated in fifth and sixth grade students.

- Most of the negative answers were given by boys.

- The lack of comprehension about the effects of bilingualism on intelligence and the students ‘ability to ratiocinate.

Likewise, the team should consider the administration of individual questionnaires focusing on items that showed students’ hesitation. Furthermore, it should carry out individual or small group interviews to those who were reluctant. Also, it should create mixed groups of students and teachers to get to know their point of view about the objectives, contents, and results of the program. These are some instruments that may help the School Management Team to analyze in detail the obtained information.

As it is shown in this research paper, it is important to know students ‘opinions on bilingual programs, since they reveal the points of view of the direct beneficiaries of this innovative experience. Because of the extraordinary effort done by the Regional Ministry of Education of the Autonomous Government of Andalusia to broaden the program offer in its territory, this information should be compiled and examined periodically since it would contribute to foster bilingualism within an autonomy that has clearly decided to stake for it.

References

Alanis, I. (2000). A Texas Two-way Bilingual Program: Its Effects on Linguistic and Academic Achievement. Bilingual Research Journal, 24 (3), 225-248.

Beebe, V. & Mackey, W. F. (1990). Bilingual Schooling and the Miami Experience. Coral Gables, FL: Institute of Interamerican Studies, University of Miami.

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., & Freedman, M. (2007). Bilingualism as a Protection against the Onset of Symptoms of Dementia. Neuropsychologia, 45, 459-464.

Blas Arroyo, J. L. (2002). The languages of the Valencian Educational System: The results of Two Decades of Language Policy. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 5 (6), 318-338.

Cazabon, M., Lambert, W. E., & Hall, G. (1993). Two-way Bilingual Education: A Progress Report on the Amigos Programs. Santa Cruz, CA: The National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity & Second Language Learning.

Consejería de Educación (2005). Plan de Fomento del Plurilingüismo: hacia un nuevo modelo metodológico. Retrieved February 26, 2007, from: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/averroes/plurilinguismo/

curriculo/modelometodologico.pdf.

Consejo Asesor para la Segunda Modernización de Andalucía (2003). Estrategias y propuestas para la segunda modernización de Andalucía. Retrieved March 1, 2007, from: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/averroes/plurilinguismo

Cummins, J. (1996). Negotiating Identities: Education for Empowerment in a Diverse Society. Ontario, CA: California Association for Bilingual Education.

Cummins, J. (2002). Lenguaje, poder y pedagogía: niños y niñas bilingües entre dos fuegos. Madrid: Morata.

Dirección General de Ordenación y Evaluación Educativa (2005). Implantación y secuenciación del programa bilingüe en las escuelas de educación infantil y en los colegios de educación infantil y primaria. Retrieved February 24, 2007, from: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/averroes/plurilinguismo/

bilingues/instrucciones2.pdf

Freeman, Y. & Freeman, D. (2005). Dual Language Essentials for Teachers and Administrators. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Gabinete de Prensa (June, 2005). Cándida Martínez informa sobre el Plan de Fomento del Plurilingüismo para el próximo curso. Retrieved March 1, 2007, from: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/educacion/nav/contenido.jsp?pag=/Contenidos/

GabinetePrensa/Imagenes/2005/Junio/Galeria280605/Galeria280605&pag

Actual=1&perfil=&delegacion=&lista_canales=&vismenu=0,0,1,1,1,1,1

García, E. (2005). Teaching and Learning in Two Languages. NY: Teachers College Press.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning: Teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Howard, E., Christian, D. & Genesee, F. (2003). The Development of Bilingualism and Biliteracy from Grades 3 to 5: A Summary of Findings from the cal/crede Study of Two-way Immersion Education (Center for Research on Education, Diversity, and Excellence). Santa Cruz, CA: CREDE.

Howard, E., Sugarman, J. & Christian. D. (2003). Trends in Two-way Immersion Education: A Review of the Research. Baltimore, OH: Center for Research on the Education of Students Placed at Risk.

Huguet, A. & Llurda, E. (2001). Language Attitudes of School Children in Two Catalan/Spanish Bilingual Communities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 4 (4), 267-282.

Lasagabaster, D. (2001). Bilingualism, Immersion Programmes and language learning in the Basque Country. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 22 (5), 401-425.

Lindholm-Leary, K. (2001). Dual Language Education. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Ramos, F. (2006). Programas bilingües inglés-español en Estados Unidos y en España: dos innovaciones en la enseñanza de idiomas. Actas del XL Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Europea de Profesores de Español (AEPE) (pp. 334-342). Valladolid, Spain: AEPE.

Ruiz de Zarobe, Y. (2005). Age and Third Language Production: A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Multillingualism, 2 (2), 105-112.

Shannon, S. & Milian, M. (2002). Parents Choose Dual Language Programs in Colorado: A Survey. Bilingual Research Journal, 26 (3), 681-696.

Torres-Guzmán, M. & Etxeberría, F. (2005). Modelo B/Dual Language Programmes in the Basque Country and the USA. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 8 (6), 506-528.

Valdés, G., Fishman, J. A., Chávez, R. & Pérez, W. (2006). Developing Minority Language Resources: The case of Spanish in California. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

The author acknowledges the support of Ana Isabel Sánchez Head of International Programs, Directorate-General for Curriculum, Instruction and Assessment; Ricardo Viñuelas, Education Technical Advisor, International Programs and Conversation Assistants; José María Rodríguez, Education Technical advisor, Exchange Programs; Elia Vila, Education Technical Advisor, Content Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), Alberto Franco, Education Technical Advisor, Faculty of the Centers, source and program development; Eduardo Jaenes Education Technical Advisor, European Programs.

Translator: Eleonora Lozano Bachioqui

Please cite the source as:

Ramos, F. (2007). Opinions of students enrolled in an Andalusian bilingual program on bilingualism and the program Itself. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 9 (2). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol9no2/contents-ramos2.html