The following is an explanation of the results that were obtained and analyzed by means of each of the instruments.

The results of the pilot application led to the conclusion that the collaborative games “Devoron” and “Temporal” contributed significantly to the achievement of the planned minimum content (MC) as well as to the fundamental transverse objectives (FTO). It is interesting to note that, in the perception of the teachers and the monitors, the more the game was applied, the greater was the impact on the achievement of the MC and the FTO. According to the parents, their participation as monitors led to their children feeling more supported and more motivated, which in turn has affected their academic performance. Likewise, the teachers report that social relations within the school have also been enhanced through the application of the games. Specifically, thanks to the game, the parent-monitors have been incorporated into the school environment, a relationship of trust has been nurtured between students and teachers and teamwork among the teachers has been fostered, thereby helping to define the FTO that the school would focus on. The game also had a positive impact on the parent-child relationship, encouraging more communication, allowing the parents to get to know their children better, etc.

The biggest obstacles that the teachers perceived in the achievement of their objectives were bad behavior on the part of some students and deficiencies in the organization of the game. The biggest challenge the teachers encountered was the lack of time to plan the session (Cereceda, 2003).

2.1 Pedagogical Application Log

In the pal the teachers indicate the themes, fundamental transverse objectives (FTO) and the vertical objectives which were most frequently furthered through the games “Devorón” and “Temporal”. The choice of themes and objectives were the responsibility of each teacher; in each grade level more than ten sessions of the games were carried out.

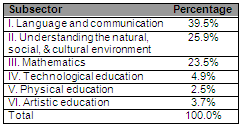

The teachers were asked to note in the PAL the objective that they were working on during each game session. From the resulting logs (n: 81) the objectives for the elementary grade levels can be summarized as seen in Table I.

Table I. Objectives for the game sessions as

stated by elementary teachers

It is clear from Table I that in the majority of the game sessions the subsectors which the teachers had as their objectives were language and communication, understanding the environment and mathematics. The other subsectors were taken into account only minimally during the implementation of the sessions.

On the other hand, the FTO that were most often considered during the planning were: “Ability to work in teams” (21.3%), “Respect for and appreciation of different ideas” (22%), “Solidarity and collaboration” (12.1%).

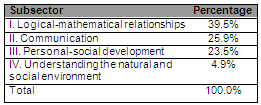

At the preschool level, the data in the logs obtained (n: 68), was organized as shown in Table II. As can be observed, the objectives most commonly pursued in the application of the games were: logical-mathematical relationships, communication and personal-social development.

Tabla II. Objectives for the game sessions as

stated by preschool teachers

Subsector Percentage

At the preschool level, the most commonly pursued FTO during the applications of the game were: “Teamwork” (26%) and “Knowing, appreciating and respecting other cultures” (22.8%).

2.2 Pedagogical evaluation guide

The pedagogical evaluation guide refers to questionnaires with closed questions about the principle themes of the study. Of the 173 guides which were collected, from parent-monitors as well as from the teachers, 67.1 % thought that the games promoted the development of intellectual skills. That is to say, that in playing the games the children learned to reason, as well as learning about the importance of teamwork and cooperating. However, 32.9% of the parent-monitors and teachers surveyed felt that the level of learning achieved was no more than average.

As far as social skills go, the majority of those surveyed thought that the games allowed the children to express their emotions, listen to others and empathize. Only 10.4% thought that the achievement of these objectives was average. The same was true for communication skills, where it was felt that the game permitted an optimal relationship between parent and teacher and between child and parent, as well as improving language skills and emotional expression. Again, just 9.2% of the respondents were of the opinion that these objectives were only somewhat achieved.

The acquisition of values on the part of the children, such as respect, solidarity, tolerance, etc., was one of the results of the game according to 91.3% of those surveyed, whereas just 8.6% felt that there was only a moderate enhancement of said values.

An explanation of these results is apparent from a more detailed analysis of comments provided by both the teachers and the parent-monitors on a small questionnaire with open questions which was included in the evaluation guide. The questions were as follows:

- “Did you like participating in this activity? Would you participate again?”

- “Indicate what you most liked about participating in this activity.”

- “Indicate what you least liked about participating in this activity.”

- “In your opinion, which elements of the game helped to achieve the FTO in this class?” (This was only for the teachers.)

A qualitative analysis of the survey responses was carried out, yielding the following categories:

2.2.1 Teachers’ evaluation guide

The responses of the teachers were classified in five categories: 1) Participation of the children in the game; 2) Advantages for learning; 3) Advantages for teaching; 4) Participation of the parent-monitors in the applications; and 5) Disadvantages identified in the game or its application. These categories allow for a more detailed evaluation of the games, their advantages, difficulties, disadvantages and pedagogical possibilities:

1) Participation of the children in the game. Initially, the children’s participation was hindered by their lack of experience in collaborative work. In the beginning there was confusion, lack of attention or uneven participation on the part of the children. However, after successive applications of the game, it became apparent that the children were learning more about the game, its rules and advantages, as is reflected in the following comments from the teachers:

“The children wanted to take part constantly, without waiting their turn” (teacher 10)

“Today the children were more fidgety than usual and it was difficult to motivate them” (teacher 25)

“[There was] disorder because it was the first time they participated in this type of game” (teacher 1)

“[There was a] lack of experience in playing the game. Some children were shy in the presence of the parent-monitors and didn’t answer the questions” (teacher 32)

“At first the integration and participation of the children was difficult” (teacher 9)

“[It was helpful] to induce the shyest students to participate in the conversation; the extroverted leaders stood out” (teacher 22)

“Knowing the game facilitated the work; the children were very motivated” (teacher 33)

2) Advantages for learning. According to the teachers, the game offered several advantages inasmuch as it helped the children learn or improved certain capacities and skills; it reinforced and increased their comprehension of the minimum content (MC).

One of the most commonly repeated themes was that the game encouraged a broader use of vocabulary by the children and improved their language expression:

“The children express themselves with much greater ease” (teacher 17)

“[It helped them] increase their vocabulary and learn new words” (teacher 13)

Although it wasn’t mentioned as often as the previous theme, the game also allowed the children to employ their intellectual skills, triggering their creativity, whether artistic or literary. In addition, it stimulated reflection on values and problem solving:

“[The] need to find a solution to the problem forces the students to reason” (teacher 24)

“Applying the materials presented in the game to the solution of problems” (teacher 32)

As previously stated, the game increased comprehension of the minimum content (MC), such as in the case of mathematics:

“To estimate the results of mathematical calculations before doing them in writing or with a calculator” (teacher 23)

“The game helped to understand some natural processes” (teacher 10)

“It reinforced content” (teacher 12)

“[It aided in] mental calculating” (teacher 17)

One of the teachers added that the game was also conducive to her students’ acquiring basic functions, specifically, in understanding spatial relations, such as:

“[The] child’s initiation in establishing spatial relations—up, down, in front of, behind…” (teacher 15)

The game also contributed to the knowledge of our culture. One theme that also stood out in the teachers’ responses referred to how the game helped the children know more about their environment, history, the regions of the country and the fruits that are typical of each of these. In addition the game aided the integration of children of native background in the class, promoted the discussion of intercultural topics and assisted in the learning of native words (from Mapuche and Aymara):

“Appreciation for their own culture…” (teacher 10)

“Locating the zones and climates where storms occur” (teacher 33)

“...the Aymara children felt more welcomed” (teacher 10)

“Observing the illustration of the Aymara children helping the adults cultivate the corn was very helpful” (teacher 25)

One of the themes mentioned most often by the teachers was that the game helped the children learn to get along together and promoted values, such as collaborative work. A frequently voiced opinion was that the game permitted the integration of the children based on a common objective as they worked as a team to solve problems. Also mentioned was the positive interaction which was sparked by the game, in contrast to the usual competitive environment; having to listen and take turns fostered respect for each other. In addition it caused an improvement in the children’s self-esteem. One of the teachers emphasized that the game encouraged solidarity among the students. Another relevant theme, even though it was only mentioned by one teacher, was that the game was conducive to integrating special needs children in the group.

“In general, the game stimulated group participation” (teacher 3)

“It provided a sense of group organization, loyal and healthy competition” (teacher 25)

“Aided in learning to share, respect each other and work in teams” (teacher 1)

“Fosters teamwork and companionship” (p2z)

“It wasn’t competitive” (teacher 8)

“Promoted working in groups, waiting your turn, respecting your peers” (teacher 28)

“Allows the children to put themselves in the place of others who suffer from the effects of inclement weather” (teacher 11)“Gives the child the confidence to do things to help others while also increasing his self-esteem before others” (teacher 9)

“Helps in understanding the presence of a classmate who participates in Teletón”6 (teacher 21)

In response to a direct question as to whether the game materials had contributed to these learning experiences, the majority of teachers answered affirmatively.

3) The participation of the parent-monitors. Generally speaking, this group received a positive evaluation, since the game permitted the parent-monitors to get to know their children better; in addition, the presence of the parents prompted greater participation on the part of the children:

“The participation of the parent-monitors in the application of the games [is important] because it allows the parents to get to know their children’s friends and classmates better” (teacher 1a)

“The presence of the mothers prompted the children to take on more roles” (teacher 19)

As a result, when there were difficulties in finding parent-monitors who were available when the game applications were scheduled, or whenever they didn’t have the support of the parent-monitors, the teachers’ evaluations would be negative, since this resulted in more numerous groups. The parent-monitors and their participation were considered essential to achieving good teamwork.

“It was difficult for the mothers to participate during the scheduled times” (teacher 28)

“[There was] little participation on the part of the parent-monitors” (teacher 4)

“In the third session three of the parent-monitors were absent, resulting in larger groups—which made the game slower” (teacher 6)

In relation to this point, one teacher mentioned the importance of training the parent-monitors before the game application:

“Only five of the parent-monitors who had received prior training arrived, so I had to train another parent who was simply dropping off her child” (teacher 3)

4) Teaching advantages. As far as the teaching process and the teacher’s task go, the teachers evaluated the game positively. Significant learning took place as the students applied the knowledge acquired through the game to their daily lives and used their previously acquired knowledge while playing:

“Through the concrete elements the children observe how life unfolds” (teacher 1)

“[The students] have been able to apply their previous knowledge through the use of the game pieces and bricks, etc.” (teacher 4)

On the other hand, one of the teachers referred to the fact that the game enabled him to know his students better:

“Knowing them better allowed a more fluid relation with them” (teacher 8)

A result widely referred to was that the game encouraged participation:

“The students’ interest in participating in the game [was observed]” (teacher 14)

“It was possible to motivate even the shyest children” (teacher 19)

Another aspect that received a favorable evaluation was that it allowed the students to share knowledge, enabling the most academically advantaged to help their classmates:

“It encouraged the most advanced students to share texts and knowledge” (teacher 34)

5) Disadvantages. The disadvantages mentioned by the teachers related to the context in which the game session was carried out and to the difficulties inherent in the game itself:

a) External Difficulties. During the sessions the teachers identified some problems of logistics which made the game application more difficult. For example, they referred to a lack of training before the application of the game. They also referred to the loss of materials used in the game and, lastly, they pointed out the difficulty of working with overlarge groups.

In addition, the teachers from one of the schools mentioned the challenges resulting from deficient infrastructure in the school itself. Reduced space did not allow the game to unfold satisfactorily.

“[One problem is] the [lack of] physical space in which to form the groups” (teacher 6)

b) Difficulties with the game itself. One of the obstacles identified by the teachers was that the cards were very difficult for the children, or rather, that the shared basket in “Devorón” wasn’t of interest to them.

On the other hand, two teachers pointed to the decontextualization of the game. They were of the opinion that it was difficult to situate the children in the game because the children in that region don’t know what a storm is.

“When applying the foods to the different regions of Chile, I noticed that the children didn’t like them” (teacher 12)

“As a game it is fun, but since they’ve never seen a storm it was necessary to prepare them beforehand so they could understand the context” (teacher 21)

“The reality that is presented in the game doesn’t relate to their own personal experience” (teacher 23)

2.2.2 Parent-monitors’ evaluation guide

The responses of the parent-monitors were classified in 14 categories, which covered their evaluation of the game in general as well as different aspects of child development to which the game contributed.

The categories that were identified are: 1) Value judgments by the parent-monitors in relation to the games, 2) Conduct of the students during the activity, 3) Emotional development and value acquisition, 4) Structure, organization and timing of the game, 5) Role of the teacher in the activity, 6) Parent and parent-monitor interest in interacting with their children, 7) Communication between parents and children, 8) Social skills, self-esteem and personality of the students, 9) Motivation and enthusiasm, 10) Collaborative games and student learning, 11) Development of motor skills, 12) Integration of parents in the school environment and the teaching-learning process, 13)

Development of oral (language) expression and thought, and 14) Cultural relevance.

The following describe some of the results from each category:

1) Value judgments by the parents and parent-monitors in relation to the games. Value judgments are understood to be those observations in which it is possible to identify the opinion which the mothers, fathers or parent-monitors have in relation to the games, their effectiveness and the entertainment value they have for those who participate in them. What stands out in the responses is the way in which the games have been an aid for the students and how appropriate their application has proven to be, both outside the classroom as well as in higher grades.

“They are helpful for the children” (parent-monitor 4)

“These games are good; I wish they had some for the higher grades” (parent-monitor 7)

“I liked it because then I can apply it at home” (parent-monitor 23)

2) Conduct of the students during the activity. This category includes comments made by the parent-monitors in relation to the students’ conduct and discipline while the game was being played. The parent-monitors commented that they were able to observe their children’s behavior and compare it to their behavior at home. On several occasions they remarked on the children’s lack of discipline or lack of attention.

“What I liked the least was that not all the children paid attention like they should and some were disruptive” (parent-monitor 16)

“[It was possible] to see the attitude of the children in the classroom, and how it is different from the way they act at home” (parent-monitor 12)

3) Emotional development and value acquisition. Here we include all those responses which refer to character values or to the students’ emotional development, which, in one way or another, was modified as a result of the application of the games. The majority of the parent-monitors were of the opinion that this activity could promote companionship, teamwork, mutual respect and a willingness to help those in difficulties; in other words, that it could strengthen their values. However, there were also some comments to the effect that some of the students showed little solidarity or respect for their classmates.

“What I liked the most about participating in this activity is that these collaborative games enabled the children to express what they feel, they teach them companionship through a common objective, which is that they all win” (parent-monitor 22)

“Some of them didn’t respect the game time” (parent-monitor 3)

4) Structure, organization and timing of the game. Included here are all the statements which critique one or more aspects of the games, their implementation in the classroom and the manner in which they were made known to the parent-monitors. Most of the comments allude to the frequency of the applications and the time spent on them, which for some was insufficient, while others argued that after a couple of applications it became too protracted, boring and repetitive. On the other hand, most of the parent-monitors were of the opinion that the use of the cards was helpful in the organization of the game, taking turns, and encouraging the equitable participation of all students, with the exception, according to some, of very large groups:

“There are too many children in the groups” (parent-monitor 4)

“Not being acquainted with the game beforehand” (parent-monitor 6)

“What I disliked the most was that it was very hard for the children to concentrate because of the large number of students in the class” (parent-monitor 24)

“The day I came to participate the children were bored with the same game. They should change the game” (parent-monitor 26)

5) Role of the teacher in the activity. This is understood to refer to the willingness of the teachers to become involved in the activity and to participate in it with their students.

6) Parent and parent-monitor interest in interacting with their children. This category covers the parents’ willingness or lack thereof to connect with their children, understand them, help them, share experiences with them and become involved in the school environment. It also includes their attempt to become acquainted with the reality that their children face on a daily basis and to understand them better through their relationship with their peers.

“Yes, I think that it is good to get to know what other children think in order to understand our own children… Yes, I would participate [again], because I like to counsel the children” (parent-monitor 9)

“What I liked the most about participating in this activity is that these collaborative games enabled the children to express what they feel, they teach them companionship through a common objective, which is that they all win” (parent-monitor 22)

7) Communication between parents and children. Here we examine whether the games had an effect—or not—on bringing the parents and children closer together; on strengthening their relationship; or stimulating understanding, mutual knowledge and feedback between them, in pursuit of the children’s integral development. In the opinion of the majority of the mothers, the games helped them draw closer to their children, understand how they think and know their concerns, interests and needs. They also commented that the games enhanced communication, generating a friendly relationship, very different from the relationship they normally have at home.

“Yes, I would participate [again] because it produced a friendship between me and my child that is very different from what we have at home” (parent-monitor 13)

“It helped us communicate more with the children, learn more about them and know what interests them” (parent-monitor 8)

“[I liked] the emotional closeness with the children, getting to know them a little and their feelings and thoughts” (parent-monitor 3)

8) Social skills, self-esteem and personality of the students. The observations in this category relate to the impact of the games on interpersonal development and the students’ self-image. The parent-monitors emphasized that the games contributed to the students’ creativity, oriented them toward group activity and created closer bonds between peers. Nevertheless, one consequence of the closer relationship was that some students adopted a lower profile, showing more shyness and embarrassment during their participation, whereas others became more assured and took on a leadership role.

“I didn’t like the fact that some children didn’t participate in the groups because they were very shy” (parent-monitor 23)

“[The game] helps them to relate to their peers better” (parent-monitor 22)

“What I liked the most was that the children fit into the group really well and they all had the right to give their opinion with the game cards, which helped their personality and self-esteem” (parent-monitor 22)

9) Motivation and enthusiasm. Here we have grouped observations about the students’ interest in participating actively in the games, as evidenced by the amusement they experience in organizing themselves and collaborating together to achieve a goal; by their enthusiasm and happiness in participating and paying attention to the activity:

“Most of the children were interested in the game and wanted to participate and collaborate” (parent-monitor 16)

“At times the children weren’t motivated and didn’t participate and then it would be difficult to carry out the activity” (parent-monitor 17)

However, it was also observed that as the students became more familiar with the game, they would lose enthusiasm and participate less in the activity.

10) Collaborative games and student learning. This section includes comments regarding the appropriation of new learning by the students, as the game related to their interests and experiences.

Upon consulting with the parent-monitors about their participation and what they most liked, they commented:

“What I liked the most about participating in this activity is that these collaborative games enabled the children to express what they feel, they teach them companionship through a common objective, which is that they all win” (parent-monitor 22)

“I liked everything because I felt good and was happy to be able to participate and know that the boys and girls learn from the collaborative games” (parent-monitor 23)

11) Development of motor skills. Comments about the influence the games had on the students’ motor development, through actions such as reaching for and throwing the dice, are covered in this section.

12) Integration of parents in the school environment and the teaching-learning process. This category was used to classify the responses which indicated an interest or lack of interest in taking part and being actively involved in the learning process. The parent-monitors emphasized the importance of activities which integrate parents and families in the school environment, thus enabling them to become acquainted with and support their children’s learning process, while helping the teachers and enjoying themselves at the same time:

“Yes, [I liked participating] because it helped to bring the family together” (parent-monitor 19)

“I liked participating because the children are more motivated when they see that their parents are interested in being in the classroom with them” (parent-monitor 23)

“Yes, because it’s nice to cooperate with the teacher and participate in support of your child’s education” (parent-monitor 16)

13) Development of oral (language) expression and thought. The observations in this category relate to the students’ capacity to communicate, express themselves clearly and respond to questions requiring prior mental organization. Most of the parent-monitors expressed how much they enjoyed participating in the application of the games, which they felt improved the children’s oral expression, helped them to think and reason and respond with enthusiasm and precision.

“Yes, I would like to participate again, because it helped them develop, think and reason” (parent-monitor 25)

“Yes, [I liked participating] because the children are now expressing themselves better. They have more personality” (parent-monitor 17)

“What I liked the least was that because of the group dynamics the children tended to be repetitive in their answers” (parent-monitor 20)

Nevertheless, some parent-monitors observed that due to the group dynamics of the game, the answers, at times, were repetitive.

14) Cultural relevance. Statements about how the game assists in the acquisition of specific knowledge, and fosters the students’ cultural enrichment by familiarizing them with Chile and its people were grouped in this category.

“Yes, [I liked it] because [the children] learn about the Chilean people” (parent-monitor 5)

“Yes, [I liked it] because it is very interesting to learn about the country” (parent-monitor 6)

“Yes, [I liked it] because it teaches the children about numbers and fruits...” (parent-monitor 5)

2.3 External evaluation log

The majority of teachers were evaluated at a high level of performance. Only six teachers received an evaluation in the middle range and none were considered to be in the low range. The average evaluation was 27 points, that is, a high level of performance.

Similarly, the evaluation of the parent-monitors’ performance was in the high range. There were only five parent-monitors whose evaluation was in the middle range and the rest were in the high range. The average number of points was 28.

In only one of the observations was the impact on the children’s learning judged to have been of a high degree. In 19 of the observations the level of impact was deemed to be medium high and in three it was qualified as medium low.

In short, the evaluation of the performance of the teachers and parent-monitors was positive since they promoted the children’s participation and reflection. In relation to the impact on the cognitive and social abilities of the children, the games tended to have a positive impact. However, in some of the sessions, this objective was not achieved, indicating the need to make a more meticulous analysis in order to determine which aspects did not allow a more positive outcome in those sessions.