There needs to be at minimum three elements or foci to an analysis of the trends or historical trajectory (including future possibilities) of supervision: 1) the domain itself (i.e., supervision); 2) the perceiver or knower (i.e., the supervision theorist, student, practitioner, supervisor, teacher leader, or administrator); and 3) the context(s).

Now, before embarking on this journey in an attempt to explicate these three concepts or facets of supervision and its trajectory, a caveat: Each of these three dimensions stand in dynamic relation to the other two. Each is contested or contestable—the domain, the perceiver, and the context—, each have multiple, sometimes contradictory distinguishing features; features that might be thought to be salient, depending upon which version of the other elements is activated or made relevant. Though there are many ways to deconstruct these elements or lenses through which to view them, one way might suffice as an example of what I mean by the dynamic interrelation of the three elements—the domain, the perceiver, and the context. Overly simplified, that example might look something like this: Someone prone to a positivist/objectivist ontology or disposition might see a simple linear progression of supervision through an historical context characterized along one dimension, for example, evolving conceptions of data gathering and its implications (or supervisors’ roles in teacher development, or what have you.) But, thankfully, people differ and are different—this is what we mean by diversity—and there are numerous ways to see or think about each of these three elements—the domain, the perceiver, and the context(s).

In order to begin to make sense of whither supervision, we must take a look at where it is now; though again, keep in mind that each of these issues is open to multiple and differing perspectives (mine and yours, to begin with, but those possible perspectives multiply as we admit more people into the conversation). Also, owing to time and space limits, this discussion of will be more cursory and evocative than exhaustive or thorough, for that I apologize in advance. So what of the three elements necessary to an understanding of where supervision might be headed—the domain, the perceiver and the contexts?

a) The domain

It’s all relative, to paraphrase Einstein.

That said, others have gestured at what supervision was, is or what it might entail. Pajak (2000) has done a superb job of demonstrating that there are multiple perspectives on one aspect of supervision, as an example, in his Approaches to clinical supervision text. Bolin and Panaritis (1992), after culling the supervision texts of the time, concluded that consensus around what supervision was, was elusive. However, they did assert that there were two areas around which a loose consensus could be constructed: 1) that supervision is important; and, more to the point of this discussion, 2) that “supervision is primarily concerned with the improvement of classroom practice for the benefit of students, regardless of what else may be entailed” (p. 31). Note: This work was published in 1992, before or at the beginning of the time when the linguistic or subjective turn and the various ‘post’ movements (post-modernism, post-structuralism, post-positivism, etc.) had been taken up or even had begun to have an impact on the field of education, let alone supervision (Waite, 1998). Supervision theory has developed some since that time.

My friend and colleague, Steve Gordon, when pressed, responded that supervision had to do with assisting teachers (S. Gordon, personal communication, October 6, 2005). I still recall how my colleague and teacher, Ray Bruce, invoked my predecessor, Edith Grimsley’s definition that supervision is something which, if not attended to, will not get done (R. Bruce, personal communication, September 20, 1990).

Funny how we grow, how times change.

Having worked with both Keith Acheson and Meredith “Mark” Gall (Acheson & Gall, 1992), at The University of Oregon, when I joined the Department of Curriculum and Supervision at The University of Georgia (USA), I was––I admit––a bit myopic: I thought of supervision in terms of clinical supervision, what Glickman, Gordon and Ross-Gordon (2004) term direct assistance to teachers. I was schooled by my early colleagues at Georgia, and not just by Ray Bruce and Jerry Firth, but by Ed Pajak, too, who related to me a bit of his own journey of coming to understand supervision; one I believed at the time paralleled my own. He let me know how he, too, had originally thought of supervision in terms of clinical supervision, but, himself under the tutelage of Ray Bruce and Jerry Firth, had expanded his conception of supervision to include staff development and curriculum development. Indeed, the supervision program at the University of Georgia included, among other courses, required courses in the areas of staff development, instructional development, curriculum development, and group development. Carl Glickman (1981) enshrined this program in his model of developmental supervision, adding, to his credit, the supervision task, area or function of action research, based on his early work with the Program for School Improvement.

Those of us who taught the introductory supervision course in Georgia’s program used not only Ray Bruce and Edith Grimsley’s (Grimsley & Bruce, 1982) text, but Oliva’s (1989) Supervision for Today’s Schools, as well. I still recall my epiphany one night as a result of one of the assignments we had for that course: The assignment, based on Oliva’s supervision issue of whether principals were more supervisor or administrator, required our students to interview a principal and ask that question or him or her. In reporting back to class that night, one of my students said her informant had replied, “when I sit, I’m an administrator; and when I’m up, I’m a supervisor”. This hit me, as one of my professors at Oregon would say, with the blinding flash of the obvious.

Though I agree with the early summary of the field by Bolin and Panaritis (1992) that consensus is/was hard to find, I would ask you to consider this, to keep this thought in mind as I develop my thesis: That nowhere and at no time did the field even remotely approximate the practice(s) advocated by the leading supervision theorists of the day; that, and that nowhere was the adoption of advocated supervisory theory or techniques uniform or even.

b) The perceiver (the knower)

At last year’s Council of Professors of Instructional Supervision (COPIS) meeting, I was introduced to the work of Schommer-Aikins (1998, 2000). Her work deals with epistemological beliefs; that is, beliefs about the nature of knowledge of the world or learning. I was immediately taken with the conceptual framework Schommer-Aikins proposed, as it seemed to me to hold the key for my making sense of one of my intellectual puzzlements, a crucial point in my praxis: As an elementary teacher, and now as a university professor, there are those particular students who stay with me, who concern or worry me long after they have moved on. One such student, for me, was a particularly hard-headed, obdurate student, who, in course reflections his instructor shared with our faculty, attacked our program (Waite, 2002); in fact, he attacked university learning with a broad brush and most vehemently. I am sorry to say that this student later assumed the principalship of my local school for a time. (He’s since moved on.) Still, and though I never had this administrator in any of my classes, and perhaps because I allowed him to represent the general case, he and his criticisms have stayed with me. One of the questions I’ve struggled with, perhaps one we’ve all struggled with in one guise or another, being educators as we are at heart, is: What would cause someone, ostensibly a student, to be so closed-minded, so resistant to the growth opportunities graduate study could offer, especially a student who is preparing to lead others’ learning?

Though I still struggle with this issue, and it’s converse—what intervention (i.e., learning or education or other experience) would help this student and students like him to grow beyond his current state—my limited understanding of Schommer-Aikins’ (1998, 2000) framework has shed light on these issues for me.

Briefly, Schommer (1994), describes five broad categories of epistemological beliefs, dimensions along which beliefs about learning cluster: the source of knowledge, the certainty of knowledge, the organization of knowledge, the control of learning, and the speed of learning.

The source of knowledge, as a continuum, ranges from beliefs that “knowledge is handed down by omniscient authority” to “knowledge is reasoned out through objective and subjective means” (p. 301). The category of the certainty of knowledge reflects beliefs ranging from “knowledge is absolute to knowledge is constantly evolving” (p. 301). The epistemological belief category of the organization of knowledge covers beliefs ranging from the belief that “knowledge is compartmentalized to knowledge is highly integrated and interwoven” (p. 301). Control of learning, as a category of epistemological beliefs, reflects beliefs ranging from “ability to learn is genetically predetermined to ability to learn is acquired through experience” and mutable (p. 301). Finally, the epistemological belief category of speed of learning has to do with beliefs ranging from “learning is quick or not-at-all to learning is a gradual process” (p. 301). Beliefs about knowledge/learning are complex and contested; that is, we might not agree, we might not hold the same perspective. Supervisors who hold differing views on any of these continua would look at teaching differently. We would view supervision differently depending on the views we hold as regards knowledge and learning.

Thinking about learning only adds to the complexity of what is supervision and where it might be heading. The preceding discussion highlights how the perceiver, the knower or the actor can be conceived of differently. There are, of course, theories of supervision which highlight the psychological or other dimension of the teacher, student or supervisor. This move of mine parallels Glickman, Gordon and Ross-Gordon’s (2004) consideration of adult/teacher growth and development along several axes. Also, and in a similar vein as theirs, I will consider the contexts within which supervision occurs, but in a slightly different key.

c) The context(s)

Like the other two elements, there are many different ways to examine this element, many different ways it can be disassembled for inspection, many different lenses through which to view it; again depending on one’s position or perspective. A critical theorist might look at how power circulates in society and how it both affects schools and operates within them (i.e., in both macro- and micropolitical respects). A sociologist from a different camp, perspective or position might look at how schools either reflect or help perpetuate social class or other, often, racial/ethnic inequalities (e.g., Bourdieu & Passerson, 1977; Coleman, 1976; or Ingersoll, 2003).

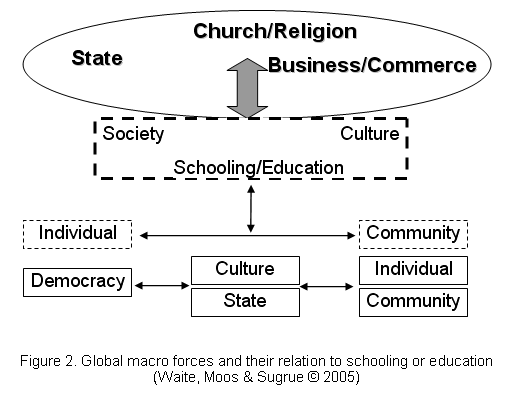

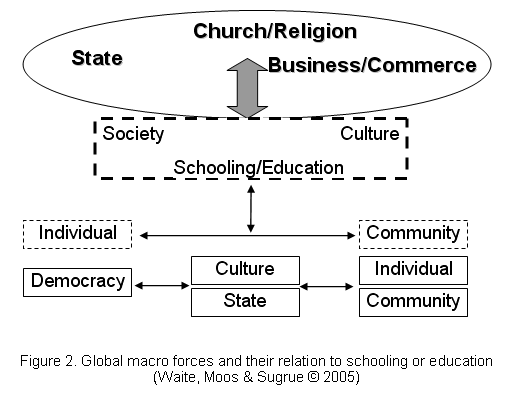

I revealed my take on this particular element (the contexts) at the COPIS meeting last year, when I gave an initial and rudimentary overview of my germinating thoughts on the global social forces and institutions that influence education and, hence, how supervision is and can be done. (See Figure 2).

I began to put my thoughts into graphic form in the time since. I enlisted two colleagues—Lejf Moos, of the Danish National University; and Ciaran Sugrue, from St. Patrick’s College, Dublin—in this project. Together, we’ve continued to tease out the particulars from the original framework, or in some cases taken different tacks altogether. For instance, I’ve been slightly troubled or dissatisfied by what I’ve felt were some shortcomings of my thinking that there were primarily three major social forces that had a disproportionate amount of influence on people, society, and through them, schooling (Figure 2.). The reason for my unease?

Though at the time I felt confident that these three major social forces did, in fact, account for most of the force(s) shaping or framing society, both at the global and the local levels, the model failed to account for other forces (e.g., forces of nature such as the tsunami, the hurricanes that hit the US recently, and the earthquake that hit Pakistan and India)—forces that appear to be super-institutional, forces which the major social forces or institutions can but react to, and often poorly. Other sources of my unease concerning the static, rigid or incomplete nature of the earlier model have to do with both the nature of models, in general, and this particular model’s unresponsiveness to varied local conditions.

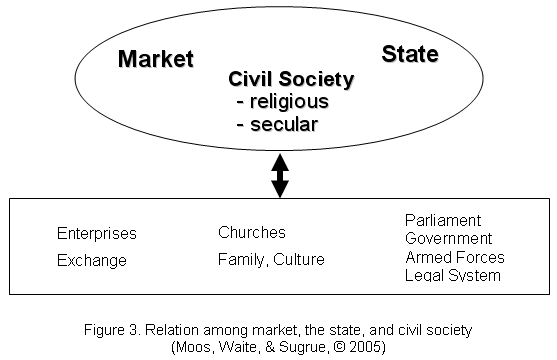

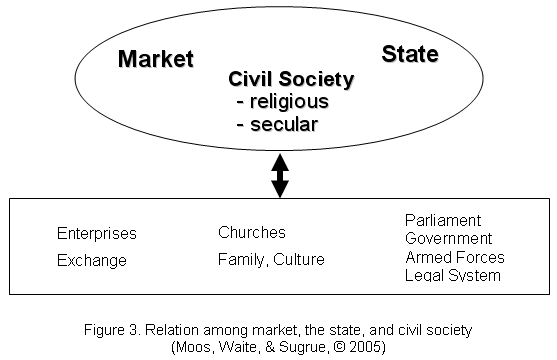

For example, my Danish colleague was quite adamant in replacing the category of the church/religion with civil society, for religion doesn’t play as large a role in public life in Denmark and much of Europe as it does in the US and elsewhere. In consultation, we’re trying to revise and refine our model to reflect more accurately his concerns and, through the process, make our model more broadly applicable (see Figure 3).

This is where we are today. As I said, there are many ways to examine this and the other two elements, and that is one of the difficulties we’re encountering: ways of thinking and ways of representation.

As I’ve hinted, models, in general, are poor representations of the phenomenon they seek to represent. Sociologist Georg Simmel (1968) wrote that,

Left to itself, however, life streams on without interruption; its restless rhythm opposes the fixed duration of any particular form. Each cultural form, once it is created, is gnawed at varying rates by the forces of life. As soon as one is fully developed, the next begins to form… (p. 11).

So why even undertake a project such as this?

I’ve done it as a thinking tool. This framework, and others like it, helps me organize my thoughts. It’s a foundational tactic in theorizing, modeling is. As a thinking tool, I hope this model and its explication—indeed, the discourse it both spawns and is a part of—might help others to think of these things and to perhaps grow in their thinking because of it and the work we’ve done.

Still in all, and I’ll say this about models, and our model, before concluding discussion of this element: the graphic representation is itself limiting, even as it permits seeing or knowing. I’m finding that, for me at least, the more interesting aspects of our model come in the in-between spaces or interfaces, where the dynamics between the social categories we’ve depicted in rudimentary, stick-figure-like outlines, play out. For instance, how do commercial and state interests play out at the local school? At your school or university? How does church/religion infiltrate the military, a state function? How does this play out at the global, national, regional, local and individual level? Analysis of the case of the US Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs would reveal some of these dynamics, and in that context.

But how do you think about, capture and portray these dynamic forces? There’s the rub. Models assist us and limit us. How do we grow beyond them? The answer to this question begins to reveal to us our epistemologies. This is nothing new, nothing revelatory. The answer is as ageless as the question, and as perplexing. It’s what’s behind The Riddle of the Sphinx (Figure 4). As we grow, what is our internal motivation; from where do we derive strength, knowledge, wisdom? And, as we age, what are the crutches we lean on? Those we cast aside?

To conclude, I want to briefly attempt to answer the question I opened with: Whither supervision? I’ll not attempt to answer the question authoritatively, exhaustively or transcendentally. (Recall Schommer-Aikins’ epistemological beliefs, especially as concerns the source of knowledge.) I will, however, be suggestive and, perhaps, provocative, in an effort to stimulate thought on the issues involved with this field or domain.

What I’d like to suggest, as I did at the outset, is that where supervision is headed, where you see supervision as headed, is dependent upon your relation or position as a perceiver to the domain and the contexts within which these issues play out.

One way to conceive of this might be this: The contexts have shifted slightly. The world has changed. Globalization, especially rapid and globe-spanning communication, has occasioned a cultural knowledge shift (Waite, Moos & Lew, 2005); or, think of it in terms of a linguistic turn or a subjective turn. For many, the status of the authority is less than it was for previous generations (our parents, perhaps we ourselves, might speak of a lack of respect on the part of individuals of younger generations). Inglehart (2003), a sociologist, writes about deep cultural schisms, a culture war, between the more traditional and conservative and the more modern (sometimes referred to as the postmodern). One of the dimensions of Inglehart’s analysis is the nature of authority. I would extend the schism, the differences, from the global to the national, professional and the local, by calling attention to what some refer to as the paradigm wars (Gage, 1989; Anderson & Herr, 1999), and, yet, go beyond even that, to what I perceive to be the guild wars between administrators, bean counters, and teachers and like-minded educators. We are witnessing the effects of this guild war in the tug-of-war over our children’s lives under repressive accountability regimes.

What I’d suggest is that those who are beating their chests and wringing their hands over the perceived demise of supervision are, perhaps, those who are nostalgic for a return to an imagined time when supervision authors were the authorities, when we spoke and they listened, when they bought our books and paid homage in other ways. A change in the relation of the knower to the domain, especially in the area of authority, threatens this hierarchical, distanced, authoritarian relation.

The way I read the field/domain today is that supervisory authority, knowledge and practice have become more diffused, not extinguished. Perhaps there is a danger here: that supervision is or will become less vibrant without a rallying point, without a central spokesperson and his/her theory or model to serve as a rallying call or thinking aid for some. Personally, I feel as though the tasks of supervision have always been part of the grand enterprise we call education. Teachers looked after their own professional development long before we started writing texts about what it was and how to do it; curriculum development, the same.

The issue, it seems to me, is really one of control (and of our position within the domain): Do we, as individuals and as a collective, control the domain? Do we foist our will upon it, and does it bend to our will? Or, are we negotiating a different position, role or relation to our field? That is a personal discussion between you, your heart and conscience; but it’s a discussion we need to engage in, individually, and collectively as well.