Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 8, No. 2, 2006

Adolescents, curriculum, and

literary competence1

Guadalupe López Bonilla

(*)

bonilla@uabc.mx

Guadalupe Tinajero Villavicencio

(*)

tinajero@uabc.mx

Carmen Pérez Fragoso

(*)

cperez@uabc.mx

*

Instituto de Investigación y Desarrollo Educativo

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California

A.P. 453

C.P. 22830

Ensenada, Baja California, México

(Received: August 14, 2006;

accepted for publishing: September 14, 2006)

Abstract

In this paper we look at access to literary texts, and analyze literacy practices in a specific context and domain: high school literature classes. We start out from a sociocultural perspective for our study of literacy events and practices. In particular, we have begun our research supported by the work of Mary Hamilton and the New Literacy Studies to identify events and their components, in order to infer the practices that give meaning to the events observed. The study was conducted in a state high school (COBACH), and in a federal high school offering two different programs: the General Diploma (GD), similar to that of the COBACH, and the International Baccalaureate Diploma (IB). The results allow us to surmise what type of reader and level of literary competency is offered by each scholastic culture.

Key words: High school, written culture, literacy practice, literary competency, the teaching of literature.

Introduction

Studies on reading (Gee, 1996; Elkins and Luke, 1999; Moore, Bean, Birdyshaw and Rycik, 1999) indicate that when confronted with written culture, readers adopt different roles and negotiate multiple identities according to the context and nature of the interaction. Thus, when coping with the role of texts written in increasingly-complex discursive communities, readers must encounter and experience new literacy practices in line with the demands of new technologies (Luke and Elkins, 2000; Gee, 2000.)

Written culture is present in many of the activities young people perform today. It is a fact that they are facing the task of deciphering and interpreting the flood of messages they receive through various media (printed, electronic), and in different contexts (home, school, work), and of and assuming a posture toward it. However, little is known about what happens in this interaction, which is ongoing and often silent.

We know, or at least the international assessments such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) seem to indicate, that in Mexico most 15-year-olds are able to decode a text, but not to interpret it—much less take a critical stand regarding it. Of all those in the sample evaluated by PISA, only 4.5% were at level 4, and only 0.5% reached Level 5, the highest on the scale; while in other countries the percentage is considerably higher: in Uruguay 11.2% are located at level 4, and 5.3% in 5; while in South Korea 30.8% are at level 4 and 12.2% at 5 (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 2004).

What is the role of the school in this process? While the study of language is an integral part of the elementary-school curriculum, both the place of reading in education, and even how much training in reading is provided to the students are unclear. The experience seems to be diluted even more in subsequent years. It is interesting, therefore, to explore the practices of reading and writing at the formal-education stage in which students are changing from adolescents into young people on their way to adulthood.

As a contribution to this line, in this paper we describe access to texts written in a particular context and domain: literature classes. It is appropriate to address this area, because despite the fact that reading is a cross-curricular competency in all curriculum domains, it is in the literature class that it takes on greater significance and becomes domain of its own.

If individual and group identities are defined through a repeated series of actions carried out by participants in an activity in a particular context (Lewis, 2001), then documenting what happens in the literature class allows us to take a look at the type of reader produced in Mexican schools. The study is part of a larger investigation documenting the availability of, and access to, written texts in language, literature and history classes in five public high schools in northern Mexico. In it, availability is understood as “the physical presence of printed materials,” while access refers to “opportunities to participate in events of written language” (Kalman, J., quoted in Carrasco, 2006, p. 59). In this regard, Kalman says that “access is an analytical category that permits us to identify how, in the interaction between participants in communicative events, knowledge, reading and writing practices, conceptualizations and uses unfold” (Kalman, J., quoted in Carrasco, 2006, p. 61).

These were the questions that served to map out the research: “What texts do students read in literature class in three specific scenarios (state high schools, general high school classes, and federal high schools offering the International Baccalaureate program)? How do students access literary texts in these three scenarios?” In the article we present the findings obtained during curricular activity.

For the study of events and literacy practices, we started out from a sociocultural position. In particular, we leaned on the current work of New literacy studies (Street, 1984, 1995; Heath, 1983; Gee, 1992, 1996; Barton 1994, Barton and Hamilton, 2000; Hamilton, 2000) to identify events and their components, which allowed us to infer the practices that gave meaning to the events observed. Using this approach, we conceived of the classroom space as a specific culture providing a context in which discourse and routine represented and defined practices valid for the group (Lewis, 2001). Thus, based on observation and video recordings of class Literature I in three contexts and two different curriculums, we identified the types of interaction predominating in each stage, for the purpose of analyzing how literary competence is constructed within each group. The study was conducted in a state high school (COBACH),2 and in a federal high school offering two different programs: the General Diploma (GD), similar to that of the COBACH, and the International Baccalaureate Diploma (IB). The results permitted us to deduce the type of reader and level of literary competency offered by each scholastic culture.

This paper is divided into three parts. In the conceptual framework the first section presents the difference between the events and the practices of literacy, based on the trend known as New Literacy Studies. The second section briefly discusses the role of literary education in the development of reading competency. Finally, after observing two different curricular proposals, the third section addresses the curricular dimension. Similarly, the results section provides a brief description and commentary on the programmatic content of Literature I in the two programs under study, with special attention to the subject to which the observed activity belongs, so as to point out some strengths and weaknesses of each program. Finally we present the findings of the observations.

I. Conceptual framework

1.1. Literacy events and practices

Research on reading has made it clear that in the school, success in reading education lies not in acquiring a set of skills, but in learning the proper use of language (oral and written) in particular communities, of which the school is only one. In this sense, students perceive the complexity of reading tasks in accordance with certain established rituals of execution established within the school community, and then move toward what is considered culturally “correct” (Greene and Ackerman, 1995).

Clearly, it is no longer sufficient to address the study of reading and writing processes without addressing the social practices each group or community accepts as culturally valid. This perspective is part of what James Gee (2000) describes as the “social turn” that various disciplines have experienced in recent years, and that in the case of reading research, has moved away from the study of the cognitive aspects of acquisition focused mainly on individual performance, and toward the analysis of the social aspects of cultural and social interaction (Street, 1995, Gee, 2000, Barton, Hamilton and Ivanic, 2000). One of these proposals is the trend known as the New Literacy Studies, whose representatives problematize the notion of literacy practices, to restore the social and cultural dimension so as to include not only the event itself, but the particular ways of thinking about the event in different cultural contexts (Street, 2003).3

Barton and Hamilton (2000) describe literacy events as the observable activities in which reading and/or writing are developed. These activities are always embedded in social contexts, and emerge from literacy practices that constitute cultural ways of using the written language. Unlike literacy events, practices are not entirely observable, since they are also found within individuals; and include values, attitudes and beliefs shared by groups representing particular social identities. In this regard, practices are shaped by the social rules governing the use and distribution of texts, and specify who can produce them and who has access to them (Barton and Hamilton, 2000, p. 8). From this perspective, literacy practices function as a conceptual tool for studying the links between the acts of reading and writing, and the social structures that give rise to them.

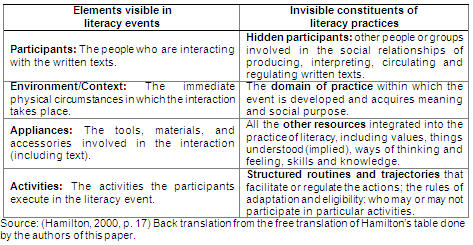

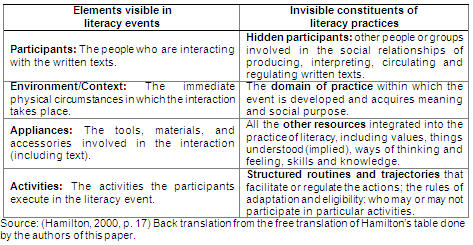

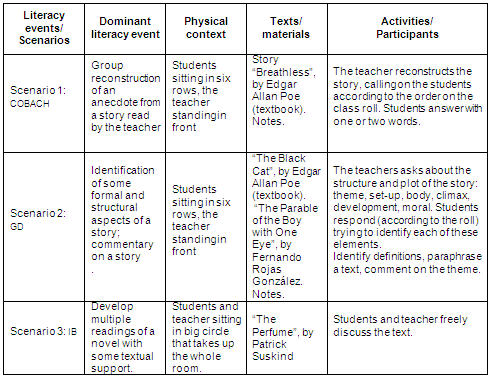

Hamilton (2000) distinguishes four basic elements of literacy events: a) participants, b) physical context, c) artifacts, and d) activities. Practices are the elements not visible, such as the social groups that produce and regulate the texts; the domain in which the event is developed; the beliefs, values, skills and budgets of the subjects; and the routines that facilitate and regulate the activity. Table I, taken from Hamilton, shows the two dimensions of this process.

Table I. Basic elements of literacy events and practice

Thus, for the case of literacy events taking place in the classroom, in analyzing the observable elements it is also of interest to identify the hidden participants and to explore the role they play in the event. An analysis of practices in the domain in question should take into account, for example, the curriculum and program contents, the decisions made within the institution and within the academy of literature teachers; the beliefs, values, knowledge and prior experience of both teachers and pupils; the speech patterns and interaction in the classroom; and the routines validated as performances appropriate within the group.

1.2 Classroom discourse

Bakhtin (1986) and Lotman (1988) have emphasized the dialogic nature of language; however, all language can be treated as both dialogic and monologic, or in Lotman’s terms, as univocal language. In classroom discourse, recitation has been described as the process by which students repeat information learned in advance, with no opportunity for discussion or disagreement (Nystrand, 1997). In the teaching-learning process, when statements are treated univocally, as in recitation, the emphasis is on “accurate transmission of information”; whereas when they are treated dialogically, as in discussions, statements/participations are used as “thinking devices” (Nystrand, 1997, p. 9). What is particularly important in these processes is not whether the language can be inherently dialogic or univocal, but whether or not teachers treat texts, students’ participations, and their own interventions as “thinking devices” (Wertsch and Toma, 1990; cited by Nystrand, 1999).

1.3. The teaching of literature in high school

Studies on the teaching of literature shows that it is in this class that “Students learn to read the social meanings, the rules and structures, and the linguistic and cognitive routines that make things work in the real world of English language use, and that knowledge becomes available as options when students confront new situations.” (Langer, 2001, p. 837). Nystrand (1997) says that when dealing with literary texts, the student learns to read and respond to the nuances of language and to the particular features of literary discourse. Other studies go further, stating that the reading training acquired by high school students in language arts courses is a determinant in economic productivity and political behavior in adulthood (Carbonaro and Gamoran, 2002).

On the other hand, theories on the teaching of literature note that studying it should enable students to challenge the discourse that shapes their experiences; and that ultimately, they must learn to “resist textbook ideology that promotes dominant cultural assumptions” (Lewis, 2001, p. 16). Thus, in many countries the teaching of literature accentuates the importance of the reader as a constructor of meaning, based on recent theories concerning the interaction between the reader and the literary text (Rosenblatt, 1978; Beach, 1993).

Because of the eminently polysemic nature of the literary text, the critical distancing that readers may experience when facing it—a posture which, on the other hand, they can assume toward any kind of text—permits them to explore the range of possible meanings, and to question why certain readers opt for one or another meaning when constructing particular interpretations, culturally validated by the social environment. This, some authors argue, should be one of the goals of the reading training students receive, especially in the higher grades. That is, in the classroom, there should be promoted activities for exploring reading repertoires accessible to individual readers (Green cited by Lankshear, 1997). For example, activities which allow the creation of intertextual links with similar themes (Hartman, 1994; Lankshear, 1997) or the deconstruction of texts (Langer, 2001, Bean and Moni, 2003), can help students learn to take a critical stance concerning what they read.

In contrast, organizing the curriculum by periods assumes that, in the best case, students read fragmented passages, as if the act of reading involved deciphering discrete entities. This position presupposes that “readers understand texts in a conceptual vacuum” (Beach, Appleman, and Dorsey, 1994, p. 696). A curriculum that includes reading multiple texts with similar themes fosters an intertextual approach; consequently, in the same way that oral discourse resorts to a polyphony of voices and experiences, in reading, the reader recognizes echoes that redefine and give meaning to what is read.

Despite the relevance that this research will provide for the teaching of literature in high school, it is noteworthy that in Mexico the high school curriculum, unlike the high school core curriculum in other countries, does not include a literature class in all its study plans, such as the technological high schools. In the care of the general high school program, it is taught for two semesters only (third and fourth).

1.4 Curriculum

Coll (1992) correctly points out that it is much more difficult to define what the curriculum is, than to specify what is meant by it. In Sacristán’s review (1998) of the term he finds that the curriculum has been analyzed from formally differentiated areas: in relation to its social function, as a project or educational plan, as a practical field, as the formal and material expression of a project, and finally, as discursive academic activity on the subject. Regarding this last point, there has been ample debate which has led to a variety of conclusions that allowing the expression of a distinction between the formal or open curriculum, and the hidden curriculum (Giroux, 1992).

If we want be specific about what curriculum means, we could say that it is the project that addresses school activities, determines intent and provides guidance for appropriate and useful actions by teachers, who are responsible for their implementation. It also provides information on what, when, and how to teach and evaluate (Coll, 1992). For us, this definition does not imply assuming that the curriculum is socially and politically neutral; on the contrary, we believe that since it is a statement of intentions, it reflects a certain concept of the school, its role in society and the socioeconomic context in which it is proposed as a school project. In this sense, analyzing the curriculum and its components allows us to recognize what particularities are presented both by the intent, and by the organization and structuring of the content; and to make inferences regarding the training one hopes to produce in the students.

II. Methodology

As Hamilton (2000) proposes, the methodology included two aspects. On the one hand, we made observations in three different scenarios for the purpose of identifying the four basic elements of literacy events; on the other, we took the proposed curriculum observed in each case, as a basis for exploring some of the non-visible aspects which give meaning to events, and largely predetermine the activities to be observed: the objectives, contents and proposed strategies.

We made observations in three different scenarios: COBACH, GD and IB. In all cases we observed two to three curricular activities that, according to Wells (1999), consist of activities relatively self-contained and aimed at achieving a purpose, and that, in turn, are part of a larger curriculum unit. The cases reported were curricular activities developed during a class and which, for the two similar contexts (COBACH and GD), covered the same curricular content: the story.

All observations were videotaped and transcribed in full. At the time of observation, a written registry of all the literacy events observed in the class was made. In it were identified the four basic elements: participants, physical circumstances, artifacts (materials) and activities.

Since in both situations (COBACH and GD) the proposed curriculum is similar, only one program is described and contrasted with the proposal of the IB. In both cases the general program was described and the consistency of the curriculum unit to which the observed activity belongs was analyzed. This allowed us to evaluate the congruence between the elements of the program: the overall objective, the course objective, the thematic objectives, the organization of the content, the strategies suggested, and the evaluation of learning (Collins, 1992).

III. Results

3.1. Literature I: General Diploma

The General Diploma curriculum (GD) has been in force since 2004, and consists of 31 courses distributed over six semesters. Training for work begins in the third semester, and spans four semesters. In the fifth and sixth semesters, in addition to the basic core, propaedeutic training is offered. The Literature course belongs to the field of knowledge Language and Communication and is composed of Literature I and II. The first is given in the third semester, and the second in the fourth. Reading and Writing Workshops I and II serve as antecedents.

The Literature I program consists of several sections: rationale, conceptual framework, objectives (of the course, unit and theme,) content unit, teaching strategy, evaluation strategy and bibliography. The groundwork of the syllabus establishes that the proposed contents are formative and informative, and have the goal of developing skills for the appropriation of literary texts. The document states that through the suggested teaching strategies, consolidation of the seven lines of curricular orientation of the curriculum is possible. These lines are: 1) development of thinking skills, 2) methodology, 3) values, 4) environmental education, 5) democracy and human rights, 6) quality, and 7) communication. The description of each of these refers to certain particularities of the course and to the possibilities of work in the classroom; for example in the line of development of thinking skills, it is specified that these can be achieved “through the analytical, critical, and evaluative reading of selected literary works, as well as developing proposed products (Bureau of High School Education [Dirección General de Bachillerato, DGB], 2003, p. 3). On the other hand, it is established that quality in teaching is possible through:

…reading texts; carrying out activities, presentations and research; and building up evidence to facilitate formative evaluation through self- and peer assessment, with the aim of achieving excellence as a student and later as an individual member of society (DGB, 2003, p. 3).

The course is 48 hours long, and the program is made up of three thematic units. Starting from the overall objective, first, the contents of each unit are presented. Then for these, there is a breakdown of thematic objectives. The proposed didactic strategy is divided into teaching strategies and learning strategies. Furthermore, the recommended instructional modality refers to the strategies possible (guided reading, cooperative work, consulting documents, and research outside of class) in the management of content. In teaching strategies, the instructor’s potential role regarding content is emphasized. In contrast, in learning strategies, notes are made regarding the possible work the student can develop in relation to the content. The three thematic units are: short narratives, the story and the novel.

3.2. General evaluation

Implicit in the program, on the one hand, is that literature be considered as a means of skills development (“The heart of the program is reading, around which language skills will develop;” DGB, 2003, p. 2). On the other hand, it is for esthetic enjoyment and recreation (“Through universal literary works [the student] will approach the wealth of his language, customs, experiences, colloquial directions, and the grandeur of the habitat”, p. 4). For the first approach, the skills to be developed are oral expression, listening, reading and writing.

3.3. Congruence between program elements: Unit II, the story

The foundational section of the program specifies the approach (constructivism) used in designing it; however, in the analysis of congruence between the fundamental elements of the program there is no clear evidence of this, besides which, certain inconsistencies were noted.

The fundamental argument notes as the general purpose of the course, the following: “reading, commentary and interpretation of texts ranging from short ones, such as fables, myths, etc.; to the story and the contemporary novel” (DGB, 2003, p. 4). As well, it states that such reading nourishes “the student with the assets and feelings of the cultures that were and are universal guidelines of thought” (p.4). Based on this approach, and related with it, it proposes that the reading of selected works and authors follow an unbroken chronological sequence in the history of literature.

Moreover, it considers that the course should be conducted as a workshop, consistent with the pedagogical approach, in which the goal expressed is to train the student as a participator. The overall objective of the course again states the “development of communication skills and attitudes through narrative works by means of the pleasant and analytical reading of selected models” (p. 7).

Notwithstanding what is expressed in the rationale and the purpose of the course, the objectives of the units are limited to asking for certain products or attitudes in relation to literature. Unit I asks for the writing of essays; Unit II, for the appreciation of the story; and in Unit III, for the evaluation of the novel as a social-artistic product. Educational intent, explicit and implicit in the preceding approaches, is imprecise in both teaching and learning strategies, as well as in the evaluation.

Unit II has the story as its theme; the formulated objective establishes that the student “will appreciate the story as a short, intense narrative genre, of artistic and social value, through pleasurable and analytical reading of universal models that allow him to extend his vision of the world around him, in surroundings of freedom and harmony (p.8).” However, there is no appreciation of congruence between the objective and thematic units, or between them and the teaching/learning activities: in the thematic goal he is requested to write critical reviews of various tales; in the teaching and learning strategies it is proposed that he read a story in order to identify structural elements, the level of rhetoric and the literary movement to which it belongs, so that he (the student) can carry out further research on the contexts of production and reception of the story in question. Finally it is proposed to instruct him and ask him to write a story so as to put together an anthology. In the evaluation strategies, there is proposed, among other things, an objective test with “questions for reviewing the elements of the story” (p. 19).

These activities reveal gaps between what is intended to be achieved as the objective (the appreciation of literary discourse through the analytical reading of representative texts), and what the student is expected to do. The reading of several stories is reduced, in the strategies, to reading a story so as to identify formal aspects—knowledge that will be evaluated with an objective test. Interaction with the text is suggested by the teacher’s comments about the story, on which the student must take notes, do a documentary investigation and prepare a critical review. There is no clear statement of what is meant by “critical review”; students are not told what resources will be provided them for the performance of the task, nor what criteria will be used in evaluating it. It is not specified whether it has to do with the essay on the story analyzed by the teacher in class, or whether the student will have contact with other stories. Above all, at no time is the student seen as an active reader capable of engaging in dialogue with peers, the teacher, and the texts, so as to opine, discuss, and express points of view on the text he has read.

At the end of the thematic unit, the qualitative quantum leap comes as a shock with the proposal that as a teaching strategy, the student be “instructed” on writing a story, and be asked to write one. This activity is not consistent with the goal of the unit, nor is there evidence that the student will be provided with enough elements to carry it out successfully. As for the evaluation, it is totally incongruous to suggest an objective test in a domain where the student is expected to perform certain tasks.

As additional data, we should point out that the comprehensive program is not what is presented to students, and the summarized program consists only of the course objective and the list of contents. Thus, students are not aware of what they are expected to accomplish and what is suggested as a way to work. The teacher is the one who decides and reconstructs the dynamics, the strategies, the products and the evaluation.

IV. Literature I (IB)

The International Baccalaureate (IB) is a rigorous academic program offered at over 2000 schools in 124 countries. Its goals include developing critical thinking skills for students of different cultures, contexts and social groups (Nugent and Karnes, 2002). Although initially conceived as a way to provide a common curriculum for the international community in transit, it has attracted attention in several countries for its academic rigor, its curriculum, its high standards and the extensive evaluation process to which its graduates are submitted. The academic achievements of students of the IB have been documented in the United States, through studies that examine their scores on national tests and their performance at the upper level (Moydell, Bridges, Sánchez and Awad, 1991).

This program is offered in English, Spanish and French. Until recently, in Mexico all the schools offering the IB were private, except for one federal public school in the northern part of the country. There are currently 39 schools, of which 36 are private and 3 are public.

The different areas of study that make up the curriculum can be studied simultaneously, although there are two levels established: intermediate and advanced. Similarly, a cap has been set on the selection of subjects. There must be at least three, and no more than four, in the top level. This implies that students must organize their study time, and that the time allocated for each subject varies between 150 and 240 hours.

In all, there are six groups of subjects students must study: Language A1 (Literature), Language A2 (foreign language), Mathematics, Experimental Sciences, Individuals and Societies, and Arts and Electives. The first three are always mandatory, while the last three are adapted to the resources and needs of each institution; therefore, they can be covered within a range of options. To get the diploma, students must meet three additional requirements: 1) pass the interdisciplinary course Theory of Knowledge, 2) develop a monograph on a topic of their choice, and 3) participate in a program called “Creativity, Action and Service. “

4.1. Overall evaluation

The IB program consists of: general and specific objectives, program (detailed description and summary), requirements and general observations, and evaluation (summary and detailed). It should be noted that students are externally evaluated, and therefore, the criteria for this type of evaluation is specified. The document provides IB teachers guidance to help them design their work programs. Thus, it is recommended that they create “a balanced and interrelated course” (International Baccalaureate Organization [IBO], 1999, p. 20). In this sense, teachers are free to adapt the content according to student needs, as long as they respect the guidelines and develop the proposed contents. The purpose of this freedom to adapt the content is to permit students to demonstrate, among other things, the ability to express ideas clearly; the mastery of language appropriate to the study of literature; a thorough knowledge of the works studied; the ability to structure ideas and arguments; and the ability to comment on the language, content, structure, meaning and importance of the texts studied.

The program establishes a particular concept of the study of literature, as it “offers tremendous opportunities for independent thinking, original, critical and clear” (IBO, 1999, p. 4). Furthermore, it is divided into four parts:

- World Literature (3 works).

- Detailed studies (4 works).

- Group works (4 works).

- Free choice by the institution (4 works).

A work is defined as a single text; two or more short texts; or a selection of stories, poems, essays or letters. It should be noted that the works should be chosen from a list of books prescribed and provided by the IBO, and the criteria are clarified for the 15 works required in 5 areas: authors, literary genres, period, place and language. Thus, it is established that “an author may choose more than one [work] within the same section of the program, but [...] in two different parts” (IBO, 1999, p. 14). The works must cover at least three literary genres; must represent at least two or three periods; must come from different places (at least two); and in terms of language, three must be translations from the original; while the detailed study should be applied to four works written in the language A1 under study, in this case Spanish. Additional criteria are the choice of works to allow students to discuss, compare and contrast different aspects such as content, themes, style and technique, and the authors’ approaches. So, beginning with the reading and detailed analysis of a series of works (15 in total, by the end of the sixth semester), there is an intent to achieve, inter alia, the following:

To promote the personal appreciation of literature [...]; to develop students’ capacity for expression for [...]; to initiate the study of a variety of texts representative of different periods, genres, styles and contexts [...]; to develop the ability to conduct a thorough and detailed analysis of a written text (IBO, 1999, p. 6).

4.2. Internal consistency between the elements of the program

The program clarifies the type of work expected to be developed with students. The general objectives refer to the development of student abilities; stipulate specific purposes: personal appreciation of literature; build a lasting interest; study a variety of representative texts and thorough and detailed analysis of a written text. These objectives are constituted as specific references that run through all the thematic units, permitting the teacher to work with the texts proposed.

One aspect of paramount importance is evaluation. This consists of the external evaluation (70%), of which the IBO is in charge, and the internal assessment (30%), provided by the teacher, but under IBO supervision. The first is divided into two written tests: a commentary-type test and a writing test, which represent nearly 50% of the overall grade, and two works of world literature written during the course (20%).

The internal assessment consists of two compulsory oral activities. This circumstance (external evaluation) influences the teacher’s activity, to the extent that it is the teacher who provides the student’s grade.

It is important to emphasize that, given the orientation of the external and internal assessments, many of the scholastic activities are aimed toward carrying out performances to be externally evaluated through written tests of development, such as: recognizing the formal aspects of literary texts and commenting on the effects they have on the reader; identifying points of view (world view) and adopting a posture; discussing the formal and ideological aspects of the text; and making a commentary with a certain degree of specialization.

V. Literacy events observed

We made observations in three scenarios: a literature class in a state high school (COBACH), a general high school (GD) and high school offering the International Baccalaureate program (IB). In all the cases we observed the Literature I class that is taught to third-semester students, between 15 and 18 years of age. In all three cases one can speak of an urban middle-class population, but it should be noted that the composition and size of the groups varies: the COBACH group consisted of 43 students (25 female and 18 male); the GD group had 48 students, (27 female and 21 male); and the IB group was composed of 20 students (14 female and 7 male).

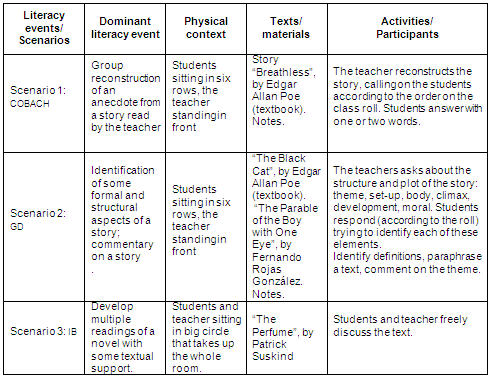

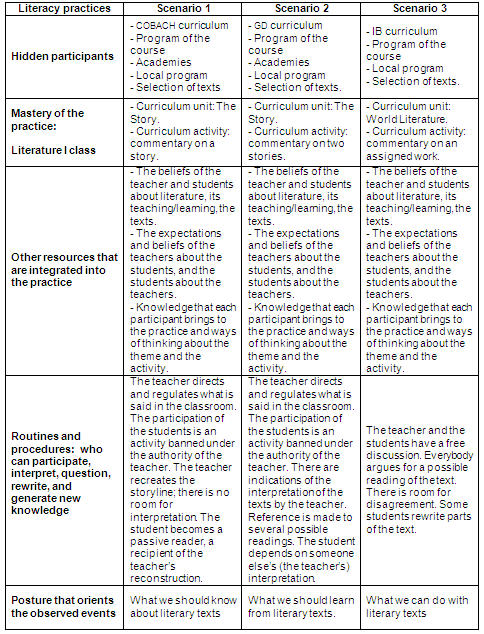

In two cases the subject under study was the genre story. In the first case it was illustrated by a commentary on a text by Edgar Allan Poe; while the second addressed two stories: one by Poe and another by Rojas González. In the third scenario a novel was discussed as part of the works of world literature at this level. Table II shows key literacy events in each scenario.

Table II. Dominant events in each group

5.1. Scenario 1

In the case of the activity observed, students should have read an Edgar Allen Poe story at home, with the help of a question guide provided by the teacher. The teacher began the class by narrating the beginning of the story, and following the roll book order in addressing some questions to specific students. In this way, the teacher was reconstructing the story, and the students’ participation consisted of brief statements (one or more words), because the questions allowed only one answer (e.g. the name of the main character, specific events, etc.). In every case, students received points for their participation, or lost points if they did not know the answer because of not having read the story.

The activity lasted 20 minutes, after which the teacher gave some details of Poe’s biography, and commented briefly on the plot of another story by the same author. The activity ended with giving the agenda for the test on this theme; this included the following topics: definition and characteristics of the story; origin and evolution of the story; a history of the twentieth-century Latin American short story; and biographies of some authors. The total duration of the class was 45 minutes.

In this activity, representative of the type of interaction with literary texts which we saw during three curricular activities, it is noteworthy that a discourse eminently dialogical and polysemic, such as the literary, was reduced to a recounting of information that could be “recited,” in this case, mostly by the same teacher; with smaller participations by the students who were evaluated as right or wrong. What is clear is that in this context, literary competence was limited, in the best of cases, to recovering the literal meaning of the text, understood as an absolute and univocal discourse, despite the wealth and multiplicity of readings which the story allows.

Furthermore, the assignment for the evaluation of the subject allowed us to see that this poor literary competence, as defined by the routines and performance rituals observed, is complemented with the memorization of factual information about the genre and the period studied (definitions, dates, data)—consistent with the objective test applied in the program of the subject.

5.2. Scenario 2

In the class observed in the second scenario, students were supposed to have read two stories, one by Edgar Allen Poe. The teacher began with Poe’s text, by asking a student, based on the class roll, about the theme of the story he had read. His response was complemented by the participation of another student, after which the teacher added further comments. The reconstruction of the story was based on the questions the teacher asked the students about the structure of the text: beginning, middle, climax and denouement. While the teacher evaluated as acceptable or unacceptable the students’ participations, it is noteworthy that all questions directed toward the students began with “In your opinion...” or “Do you agree that...”, which implies a private, complementary reading, and the possibility of an alternative reading. This allows us to infer that, although it was the teacher who ultimately provided the “correct” reading of the text, the way questions were asked allowed us to infer three fundamental aspects of this practice: a) the polysemic nature of literary texts, b) reading as a process of construction based on a particular point of view, and c) the active role played by readers with regard to the text.

In her comments on the text, the teacher incorporated some data from the author’s biography in an attempt to find parallels with the work, and finished by asking about the moral of the story. The answer given by one student was taken up and expanded by the teacher. All participations were taken into account, and counted toward the assessment of the subject studied. This activity lasted 18 minutes.

The second round of questions had to do with the story by Francisco Rojas González. The teacher began with several questions about the author’s biography, and asked for his definition of this literary genre. When a student read her response, the teacher asked her to paraphrase it and explain what she understood about the text she had read; when the teacher got no answer, she rephrased the question by paraphrasing the text and addressing specific aspects of the topic. Several students responded, and the teacher used examples to illustrate the concept of the story posed by the author. After further questions about the author’s life and ideas, the teacher again asked about the theme and some events in the story. While up to that point the questions had been directed towards the formal and literal meaning of the text, the following questions challenged the ideology of the story expressed in the author’ particular view of discrimination and the characters’ ignorance. Both the students’ responses and the teacher’s comments illustrated their involvement with examples from everyday life. The teacher asked several other questions relating to the identification and meaning of various metaphors, and concluded her commentary on the text by offering her own interpretation. This activity lasted 20 minutes.

In the context of this class, literary competence is defined as the identification of some formal aspects of the text, the knowledge of some important data about the author, and a budding ability to infer meanings and interpret the text. However, by the way questions were posed, the teacher made it clear that literary discourse can be read from different perspectives. Furthermore, the ideology of the text was addressed, at least superficially, in the commentary on the moral of the first text, and in the treatment of certain themes (such as racism) in the second. It is worth mentioning that in the second case, the teacher’s comment with extra-textual examples showed an ideology framed in some assumptions of the dominant culture, as regarding the themes of the story.

5.3. Scenario 3

The class began with students’ questions about the characteristics of the essay that would form the basis of their evaluation for that period. This essay was a critique and personal commentary on Suskind’s novel, Perfume, and it would be an exercise in preparation for external evaluations. In their questions, the students illustrated their concerns with personal commentaries about the novel, in order to clarify the type of participation expected in the written evaluation. Some interventions alluded to the commentaries and suggestions that more advanced students of the program (5th semester) provided them as part of IB routines in that institution. In her responses, the teacher emphasized the need to provide a personal reading with a clear argument, supported with textual evidence.

These questions were the basis for the discussion predominating during the class, which did not follow a pre-defined line. Unlike the two previous scenarios, this class had an informal tone (evident in the use of the familiar tú) prevailing between students and teacher, to question and “compete” for the forum with participations, which were often simultaneous. In this discourse, even though the teacher gave his partial interpretation of the events of the novel, the contributions of the students were validated within the classroom culture as legitimate readings, complementary and sometimes opposing those of the teacher or their peers. Thus, there were approached such issues as the construction of the main character’s identity, his motivations and his world view; inferences and questions were formulated about the outcome of the work, and there was developed a rewrite of particular events with versions differing from those in the text. In this case one can speak of a real discussion, because although the teacher participate actively in constructing the readings of the work, it was clear that the course the discourse took was marked by students’ speeches, comments and questions.

By the nature of the events observed, it is clear that in the IB context in this institution, literary competence is understood as an individual and collective questioning about and directed toward the literary text. This becomes a posture that allows students to infer meanings; construct a personal interpretation; compare and defend their reading before their peers and the teacher’s authority; and ultimately rewrite the text; highlighting the ideological assumptions in what is expressed.

It is worth noting that these practices, although they may be due in part to the characteristics of the IB program (curriculum, assessments, hours, number and type of students), are at the same time, products of the routines that validate the plural and collective reading of literary texts.

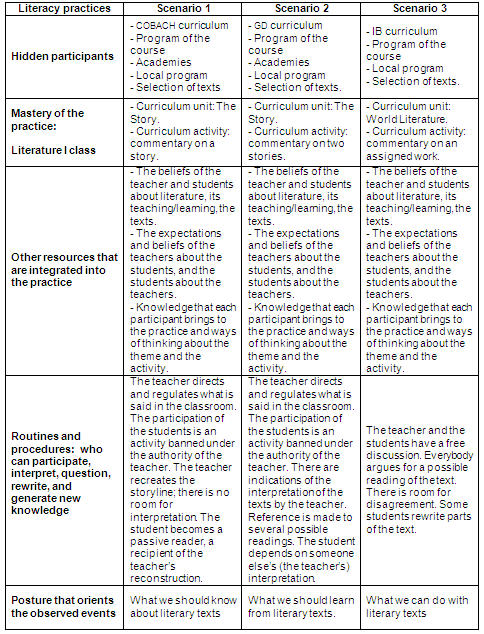

5.4. Literacy practices

Table III highlights some important aspects of the practices that appear to confer meaning on the events observed.

VI. Discussion

The events observed in each scenario allow us to infer particular aspects of the practices in which they are registered. In the first scenario, the question that seems to guide the participations of the teacher and students is, “What should we know about the literary text?” The answer to this question, based on the events observed, refers to literal meanings of the literary text: the names of the characters, the sequence of events, the outcome. Both the teacher and students seem to understand the literary language of as univocal language. There is no evidence that even at this level, students would be independent readers. Access to texts is restricted and limited, and mediated by the teacher’s authority.

In the second scenario this question seems to predominate: “What should we learn from literary texts?” In this case, the participations retrieved the formal aspects of the text, the meaning of certain figures of speech, and some ideological aspects read between the lines. Students depended on the study guide authorized by the teacher to perform these tasks. Access to literary texts indicates a broader opening, but is mediated by the authority and experience of the teacher.

The last scenario is constructed as a space for the negotiation of multiple readings (and readers). Both teachers and students seem to answer the question, “What can I do when confronted with a literary text?” In the negotiation, all participants were posited as valid sources of knowledge. Access to the literary text is given by different routes, of which the teacher is one among many.

VII. Conclusions

Observing the same curricular activity (interaction with texts representative of the short story genre) in two different contexts, allows differentiating the adaptation of the curriculum teachers design, together with its nuances and interpretations. Thus, the scholastic culture observed in these three scenarios establishes and constructs disparate literary skills: in the first case, reading is understood as the superficial deciphering of a univocal discourse, through which the student becomes a passive reader, dependent on reconstruction foreign to him/herself, and embodied in the teacher’s authority. Valid sources of knowledge are primarily the teacher, and to a lesser extent, the text; students’ participations function as a reading control for evaluating the activity. There is no evidence for the training of autonomous readers, much less critical ones. However, these activities are largely consistent with the proposed teaching strategies for this unit in the corresponding program.

In the second scenario, literary competence is constructed on three levels: the identification of certain structural aspects of the story, such as the relationship between life and work of the author, and as commentary on the ideology of the text based on the treatment of specific topics. Despite the formulation of questions alluding to particular readings, and addressing important aspects of the literary texts, the rigid structure of the discourse and the time devoted to each text did not allow delving deeper into the issues discussed. Nor did it lead to more satisfying participations on the part of the students—which give preferentiality to the teacher’s reading as the only valid interpretation. Again, the limitations of dealing with an inadequate number of class hours and many groups, as well as a superficial approach to the contents proposed in the program, are much in evidence.

The scholastic culture described in these two contexts differs greatly from that of the third scenario. In the latter were the students were the ones who chiefly structured the classroom discourse; a discourse that projects, to a certain extent, the polyphony and dialogism of the literary text. In this context, students are constructed as readers, based on their ability to question each other and the text itself, so that they themselves are constituted as one of the legitimate sources of knowledge.

It is valid to ask whether or not these findings are the result of the prescriptive approach that still seems to predominate in literature teaching in Mexico. If so, the experience of a practice like the one described here may offer more clues to providing a positive influence on students’ training in reading.

References

Bakhtin, M. (1986). The dialogic imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Barton, D. (1994). Literacy: An Introduction to the ecology of written language. Oxford: Blackwell.

Barton, D. & Hamilton, M. (2000). Literacy practices. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton & R. Ivanic (Eds.), Situated literacies. Reading and writing in context (pp. 7-15). London: Routledge.

Barton, D., Hamilton, M., & Ivanic, R. (2000). Situated literacies. Reading and writing in context. New York: Routledge.

Beach, R. (1993). A teacher’s introduction to reader-response theory. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English.

Beach, R., Appleman, D., & Dorsey, S. (1994). Adolescents’ uses of intertextual links to understand literature. In R. Rudell, M. Rudell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theroetical models and processes of reading (pp. 695-714). Newar, DE: International Reading Association.

Bean, T. & Moni, K. (2003). Developing students’ critical literacy: Exploring identity construction in young adult fiction. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 46, 638-648.

Carbonaro, W. & Gamoran, A. (2002). The production of Achievement Inequality in high school English. American Educational Research Journal, 39, 801-827.

Dirección General de Bachillerato. (2003). Programa de la asignatura: Literatura I. Mexico: Author.

Carrasco, A. (2006). Entre libros y estudiantes. Guía para promover el uso de las bibliotecas en el aula. Mexico: Consejo Puebla de Lectura, A. C.

Coll, C. (1992). Psicología y currículo. Barcelona: Paidós.

Elkins, J. & Luke, A. (1999). Redefining adolescent literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 43, 212-215.

Gee, J. P. (1992). The social mind: language, ideology, and social practice. New York: Bergin & Garvey.

Gee, J. P. (1996). Social linguistics and literacies: ideology in discourses. New York : Falmer Press.

Gee, J. P. (2000). The New Literacy Studies: from ‘socially situated’ to the work of the social. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton, & R. Ivanic (Eds.), Situated literacies. Reading and writing in context (pp. 180-196). New York: Routledge.

Greene, S. & Ackerman, J. (1995). Expanding the constructivist metaphor: A rhetorical perspective on literacy research and practice. Review of Educational Research, 65, 383-420.

Hamilton, M. (2000). Expanding the new literacy studies: using photographs to explore literacy as social practice. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton & R. Ivanic (Eds.), Situated literacies. Reading and writing in context (pp. 16-34). New York: Routledge.

Hartman, D. (1994). The intertextual links of readers using multiple passages: A postmodern/semiotic/cognitive view of meaning making. In R. Rudell, M. Rudell, & H.

Singer (Eds.), Theroetical models and processes of reading (pp. 616-636). Newar, DE: International Reading Association.

Heath, S. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Langer, J. (2001). Beating the odds: Teaching middle and high school students to read and write well. American Educational Research Journal, 3, 837-880.

Lankshear, C. (1997). Changing literacies. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Lewis, C. (2001). Literary practices as social acts. Power, status and cultural norms in the classroom. Mawah, NJ: Lawrence, Erlbaum Associates.

Lotman, J. (1988). Text within a text. Soviet Psychology, 26, 32-51.

López Bonilla, G. (in press). Ser maestro en el bachillerato: creencias, identidades y discursos de maestros en torno a las prácticas de literacidad. Revista Perfiles Educativos.

López Bonilla, G & Rodríguez, M. (2006). La enseñanza de la literatura en la educación media superior: Una mirada al bachillerato internacional. Revista Textos, 43, 87-96.

Luke, A. & Elkins, J. (2000). Re/mediating adolescent literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 43, 396-398.

Moore, D. W., Bean, T. W., Birdyshaw, D., & Rycik, J. A. (1999). Adolescent literacy: A position statement. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 43, 97-12.

Moydell, J., Bridges, J., Sánchez, K., & Awad, P. (1991). Lamar High School: Instructional tracks and student achievement (1990/91). (Report No. XPT32390). Houston, TX: Houston Independent School District. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED337503).

Nugent, S. & Karnes, F. (2002). The advanced placement program and the International Baccalaureate Programme: A history and update. Gifted Child Today Magazine, 25, 30-40.

Nystrand, M. (1997). Opening dialogue. Understanding the dynamics of language and learning in the English classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2004). Learning for tomorrow’s world. ¬First results from PISA 2003. Paris: Author.

Organización del Bachillerato Internacional (1999). Lengua AI. Geneva: Author.

Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Street, B. (1984). Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Street, B. (1995). Social literacies: critical approaches to literacy in development, ethnography and education. New York: Longman Publishing.

Street, B. (2003). What’s “new” in the New Literacy Studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 5, 77-91.

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Translator: Lessie Evona York-Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

1This article reports partial results of the project: How Mexican youth read: A comparative study of the teaching of history and literature in high school, key SEP-2003-CO2-45 513, funded by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT ) and The training of critical readers in two types of high schools, key FOMIX-2003-01, funded by the BC-CONACYT Joint Fund.

2(Editor's Note) The state high school (College of Bachelors or COBACH) is a decentralized agency of the Mexican state, created by presidential decree September 26, 1973, and offering upper secondary-school studies at the national level, as part of in-school and open modalities. (To find out more, visit: http://www.cbachilleres.edu.mx/).

3Considering the term practice of literacy on a more abstract level than the event itself, Brian Street (1995) notes that this term implies both the activity and the conceptualizations of reading and writing about that activity. In this sense, the concept is distinguished from a more restricted use of the expression in that it alludes to what is done or put into practice.

Please cite the source as:

López Bonilla, G., Tinajero, G. & Pérez Fragoso, C. (2006). Adolescents, curriculum and literaty competence. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 8 (2). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.ens.uabc.mx/vol8no2/contents-bonilla.html