Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 8, No. 2, 2006

Translation and Adaptation of Tests: Lessons Learned and

Recommendations for Countries Participating in timss, pisa

and other International Comparisons1

Guillermo Solano-Flores

guillermo.solano@colorado.edu

School of Education

University of Colorado, Boulder

249 UCB

Boulder, CO 80300-0249

United States of America

Luis Ángel Contreras Niño

angel@uabc.mx

Instituto de Investigación y Desarrollo Educativo

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California

A.P. 453

C.P. 22830

Ensenada, Baja California, México

Eduardo Backhoff Escudero

backhoff@uabc.edu.mx

Instituto de Investigación y Desarrollo Educativo

Universidad Autónoma de Baja California

A.P. 453

C.P. 22830

Ensenada, Baja California, México

(Received: November 21, 2005;

accepted for publishing: July 27, 2006)

Abstract

In this paper we present a conceptual model and methodology for the review of translated tests in the context of such international comparisons as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). We also present the results of an investigation into the quality of the Mexican translation of the TIMSS-1995 into the Spanish language. We identified translation errors in a significant percentage of the items, as well as relatively high correlations between the severity of translation errors and the items’ p-values. These findings indicate that our error-coding system is highly sensitive to test-translation error. The results underscore the need for improved translation and translation-review procedures in international comparisons. In our opinion, to implement the guidelines properly for test translation in international comparisons, each participating country needs to have internal procedures that would ensure a rigorous review of its own translations. The article concludes with four recommendations for countries participating in international comparisons. These recommendations relate to: (a) the characteristics of the individuals in charge of translating instruments; (b) the use of review, not simply at the end of the process, but during the process of test translation; (c) the minimum time needed for various translation review iterations to take place; and (d) the need for proper documentation of the entire process of test translation.

Key words: Educational tests, international tests, test translation, TIMSS, PISA.

Introduction

During the past two decades, the practice of translating and adapting instruments for educational measurement into other languages or for different cultures has become more frequent as a result of a trend toward a global economy. The results of international comparisons such as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the Programme for International Student Assessment (pisa) have a more and more profound influence on public opinion and on the educational policies of the participating countries, whose performance in relation to other countries is an indicator of academic progress.

One consequence of the current boom in international comparisons has been the development of new and more sophisticated procedures for translating tests; these procedures have the goal of ensuring that test items are equivalent in multiple languages, although there are important cultural differences among the participating countries. A key component in international comparisons is the use of a set of guidelines that would ensure a minimal consistency in the procedures used by the different countries. For example, the nations participating in TIMSS-1995 used the guidelines for the translation of evidence produced by Hambleton (1994), commissioned by the International Test Commission (ITC); after 2007, a new set of guidelines will enter into force (see Hambleton, 2005).

Another key component in international comparisons is the use of a system for reviewing test translations. This system is based on the use of a translation-review team in which none of the members are translators from participating countries. The translations of TIMSS-1995 were certified by a third body before being released for application by the participating countries (see, for example, O’Connor and Malak, 2000).

This article is directed toward the professionals involved in the translation of tests in international comparisons. In it we present evidence that, although necessary, the guidelines for the certification of translation quality may be insufficient to ensure adequate translation of the instruments. The basic implication of this work is that, in order to benefit from their participation in international comparisons, countries should be sure of having internal-review procedures that allow translation guidelines to be implemented in a manner sensitive to subtle, but very important, aspects of language use in each country.

The article is divided into four sections. In the first section we describe a conceptual model for reviewing tests. This model includes a wider range of translation aspects than those normally included in other procedures. These aspects relate to test production, curricular representation and the social aspects of language use. In the second section we describe our procedure for coding errors in translation, based on the facilitation of discussions by interdisciplinary committees of specialists. In the third section we present empirical evidence for the sensitivity of our review model. This evidence comes from our analysis of the Mexican translation of the TIMSS-1995 and of a project currently underway, in which we analyze the quality of the Mexican translation of the PISA-2003. We conclude with a set of recommendations for countries participating in international comparisons.

I. Conceptual framework for the review of test translation.

The development of our conceptual framework was based on the combined use of regulatory documents for test translation developed by the TIMSS (Hambleton, 1994, van de Vijver and Poortinga, 1996), procedures for verifying the quality of TIMSS-test translation (Mullis, Kelly and Haley, 1996), criteria used by the American Translators Association (2003), standards and criteria used by PISA to determine the cultural appropriateness of test items (Grisay, 2002, Maxwell, 1996), and evidence from our own research on the effect of morphosyntactic characteristics of the items and socio-linguistic and epistemological factors, in students’ interpretations of the items in the areas of Natural Sciences and Mathematics (Solano-Flores and Nelson-Barber , 2001, Solano-Flores and Trumbull, 2003, Solano-Flores, Trumbull, and Kwon, 2003).

Our conceptual framework is based on five premises: (a) the inevitability of error in translating tests; (b) the dimensions of mistranslation; (c) the relativity of the dimensions of error; (d) the multidimensional nature of translation errors; and (e) the probabilistic nature of the acceptability of an item’s translation. We next explain each of these premises.

1.1 Inevitability of error in the translation of evidence

In theory, it is impossible to achieve construct equivalence in two languages, because each language is specific to an epistemology (Greenfield, 1997). Furthermore, translation implies that a test version in the original language, and the version in the target language, have been developed with different procedures. The test in the source language has been developed through a long iterative process that includes multiple reviews and piloting with samples of students. In contrast, the process of translating the test happens in a relatively short time, limiting the opportunity to pilot the test translation with students and refine the wording of the items (Solano-Flores, Trumbull and Nelson-Barber , 2002).

1.2. Dimensions of mistranslation

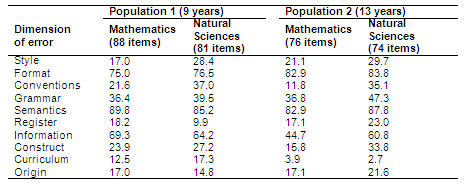

Due to the inevitability of error, our model is particularly concerned with the detailed classification of translation errors. For our review of the TIMSS-1995 translation, which we will discuss in the next section, we developed a set of 10 dimensions of translation errors (see Table I). Obvious dimensions have to do with accuracy of translation, grammatical correctness (grammar, semantics) and the editorial and production characteristics of translated tests (style, format, conventions). Other dimensions consider the agreement of the translation with the use of language, and with its usage in the target population in their social and instructional contexts (register), content (information, construct) and the curricular representation (curriculum). A tenth dimension (origin) highlights the fact that faults in the item in the source language can be transferred to the translation.

Table I. Dimensions of test mistranslation

These dimensions of error should not be construed as exhaustive or universal. Depending on the nature of the tests translated, each dimension may have a greater or lesser relevance, or must be specified in more or less detail, according to the test content which it purports to measure, and to the resources available for the project’s translation. For example, while on the TIMSS tests the translation of technical terms must be examined on the basis of their alignment with the curriculum implemented in specific grade levels, on the PISA test it is more relevant to consider the translation on the basis of nationwide language use.

1.3. Relativity of error dimensions

A perfect translation is almost impossible to achieve, because there is a tension between the dimensions of error. For example, using a key word in the translation of an item more often than in the original version can make a difference in the amount of information critical for understanding a problem (information dimension), but at the same time, the inconsistency may be necessary to ensure that there be a natural syntax based on the conventions used in the target language (dimension of grammar.)

1.4. Multidimensionality of translation errors

The linguistic properties of an item are interconnected. One consequence of this interrelation exchange is that a characteristic in the translation of an item may belong to more than one error dimension. For example, improper insertion of a comma in a sentence may not only violate certain conventions in writing the target language (dimension grammar), but may also alter the meaning of a sentence (semantic dimension).

The translation of an item cannot be either completely adequate or completely inadequate. It is more appropriate to think of the quality of the translation of an item in terms of its acceptability. Because of the multidimensional nature of translation errors, translation errors are allowable in virtually any item. However, this error should not be interpreted as fatal error. Our model postulates that individuals have the cognitive capacity to handle translation errors so that, within limits, these do not affect the performance of individuals on tests. At the same time, some minor errors which may not be important separately, can, together, affect the performance of examinees.

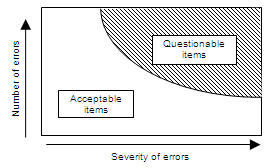

1.5. Probabilistic nature of the acceptability of an item’s translation

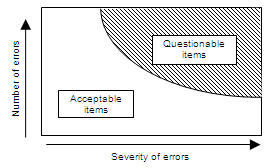

According to our conceptual framework, the analysis of errors in translation can be made from a probabilistic approach. Linguistically acceptable items are not completely free from error, and not all items with errors are necessarily questionable. Figure 1 shows the acceptability (or questionability) of the translation of an item as a probability space. Such a probability space is bounded by the number of translation errors (vertical axis) and by the severity (horizontal axis) of these errors (Solano-Flores, Contreras-Niño, and Backhoff-Escudero, 2005). The translation of an item is in the area of acceptability (white area) because it has few errors, or because it has several errors that are mild. In turn, the translation is in the area of questionability (shaded area) because it has few overly severe translation errors, or because it has many mild errors.

Figure 1. Probability space of acceptable and questionable

ítems as defined by the frequency and severity of errors in translation.

1.6. Translation Review Procedure

The translation-review procedure we have used to revise translations has two critical components: (a) the use of multidisciplinary teams of reviewers, and (b) the encoding of errors by committees.

1.7. Multidisciplinary teams of reviewers

This review of test translations has been guided by the principle that the various dimensions of translation error cannot be examined in sufficient detail if the participants in the review committees are not sensitive to different forms of use in the language. The composition of a translation-review committee should reflect the characteristics of the test, as well as its purpose and content. For example, a committee in charge of reviewing the translation of a science test should include instructors with experience teaching students of corresponding scholastic levels; curriculum specialists; linguists; professional translators and specialists in measurement. Teachers know the formal and colloquial use of language in the context of teaching (e.g. in textbooks and in the classroom); curriculum specialists can determine whether the terminology used in the translation of the items corresponds to the level of complexity in the official curriculum; linguists can examine the structural, functional and semantic aspects of the translation; translators can assess the accuracy of the translation from a technical perspective; and measurement specialists can analyze the cognitive demands generated by the linguistic properties of the items in the original language and in the translation.

1.8. Procedure for revision of the translation

The review of the translation of the items is done through group discussions facilitated by the researchers of the project. Because this process brings to light many errors that cannot be detected by other procedures, the discussion of a single item can last up to 45 minutes. This time is not very different from what, on the average, should be devoted to an item when it is developed in its original form (see Solano-Flores, in press).

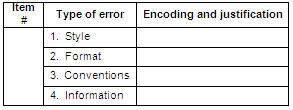

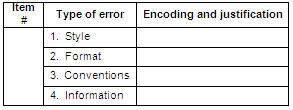

Before the formal proofreading sessions, there is carried out a one-or-two-day pilot session with the translation committee, during which committee members are trained on the use of an encoding protocol like the one shown in Figure 2. During this pilot session the definition of the dimensions of error is perfected, so that this definition corresponds to the specific characteristics of the test to be reviewed. The procedure for reviewing each item is the following:

Table II. Section of the protocol used

to encode translation errors

- Each reviewer was given a printed copy of the item in Spanish. She was asked to read it and answer it as if she were a student taking the test. This was done in order to ensure that each reviewer would become familiar with the item, would be aware of the kind of reasoning that gave rise to it, and would mull over the type of knowledge needed to answer it correctly.

- The original version of the item in English was projected on a screen so that the reviewers could compare the versions of the item in both languages. However, they were previously asked not to look at the projection until they had answered the item.

- The reviewers examined the item, and independently recorded their comments into the evaluative format illustrated in Figure 2. In this format, they recorded the types of translation errors they identified, and where necessary, justified their encodings.

- Next, the reviewers coded translation errors according to their areas of expertise. Thus, the psychologist and the measurement specialist focused on the dimensions of style, structure, conventions, origin, and construct; the translator, on the dimensions of style, format, grammar and semantics; the linguist, on the dimensions of grammar, semantics and registration; and teachers and curriculum experts, on the dimensions information, content and curriculum. However, reviewers were asked to indicate any errors they detected, even if these did not belong to their areas of expertise; and to participate in the discussion of all errors.

- The encodings of the translation errors were discussed by all committee members until a consensus was reached. Often this discussion allowed the committee to identify errors that were not detected by any reviewer working individually. This was usually in the case of origin (see Table I), i.e. defects in the item in the original version.

- During the translation-review session, teachers and content experts had access to essential curriculum documents such as the official textbooks and teachers’ guides. In addition, the committees were provided with information released by the evaluation program (e.g. TIMSS or PISA) on the content of the items and the knowledge and skills intended to be accessed by them. These documents allowed the reviewers to make appropriate interpretations of the items’ intended meaning, both in the source language and in the target language.

- Once they reached a consensus on how to codify the errors in an item’s translation, the reviewers modified their original, individual encodings on their individual formats, so that these reflected the decisions made by the committee.

The quality evaluation of a test translation is based on a statistical analysis of the errors observed in all the items. We have found that the best indicators of the quality of a test translation are those based on the number of different error dimensions identified in the items (Solano-Flores, Contreras-Niño, Backhoff-Escudero, 2005). For example, a formatting error in an item is recorded as one, even though there may be several formatting errors in the same item.

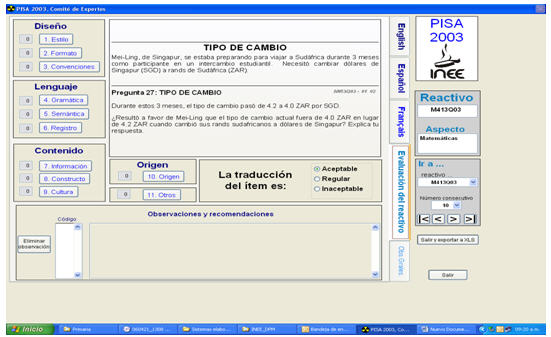

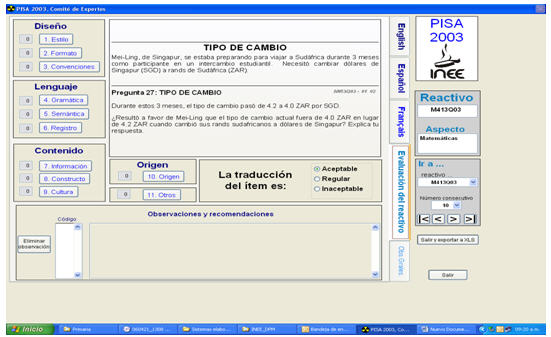

We have recently introduced an improvement in the operational aspect of the procedure.2 Specialized software has been used to review the Mexican translation of PISA-2003. This software allows reviewers to see the evaluation screen (see Figure 3 and translation) used for online entry of the encodings on which the reviewers agree concerning the quality of the items’ translation. The program allows reviewers to see both the translation of each item, and the original language version (in the procedure used for the translations of PISA-2003, the items were translated independently of the two source languages: English and French). Using a computer program allowed us to enter the codification data for each item during the committee members’ discussion (Solano-Flores, Contreras-Niño, Backhoff-Escudero and Andrade, 2006). This modificación has the potential to reduce the time and costs of the translation-review process.

Figure 2. Example of the evaluation screen for the online entry of translation-qualityassessment data (Program developed by Edgar Andrade, of the INEE)

II. Sensitivity of the model for test-translation review

2.1. Mexican translation of TIMSS-1995

Data on the implementation of the TIMSS-1995 in Mexico are practically unknown, because the country withdrew its participation after the data had been collected, but before the results were published (Backhoff-Escudero and Solano-Flores, 2003).

With the creation of the National Institute for Educational Evaluation (INEE) in 2002, Mexico entered an era of public awareness of evaluation and renewed expectations of transparency on the subject of educational issues, especially in the context of accountability.

As part of the efforts to evaluate the previous work of the education system in connection with testing, the INEE funded a series of studies that contribute to getting the maximum benefit from Mexico’s participation in international comparisons. In this study we used the methodology described in the previous section to examine the quality of the Mexican translation of the TIMSS-1995.

2.2. Sample items

Most of the data derived from the implementation of the TIMSS-1995 in Mexico were destroyed (a fact which in itself shows the need to develop appropriate mechanisms for documenting development and test-translation processes). However, shortly after the creation of the INEE it was possible to recover the blank copies of all the examination booklets used by the students of Population 1 (age 9, third and fourth years of primary education) and to the students of Population 2 (age 13, first and second years of junior high school).

It was also possible to retrieve information about the p-values of some items (the proportion of students who answered the questions correctly) for the 1995 application (which took place as part of Mexico’s participation in the international comparison) and the application made by the General Directorate of Evaluation, Ministry of Education, in 2000. The corpus of items in our study consisted of 88 items for mathematics and 81 for natural sciences, applied to Population 1; and 76 items for mathematics and 74 for natural sciences, applied to Population 2 (a total of 319 items.)

In order to examine (albeit in a limited manner) the potential impact of translation quality on student performance, we analyzed the correlation between our measures of translation quality with the p-values of 42 mathematics items and 39 natural science items, applied to Population 2.

2.3. Participants

Students. The correlation analysis was based on p-values of the items calculated using the student records of Population 1 (N = 10.122 for third grade, and N = 10.194 for fourth grade); and those of Population 2 students (N = 12.809 for first level and N = 11.843 for second level of junior high school).

Committees of reviewers, and review process. There were set up two translation-review panels composed of specialists with diverse backgrounds and professional

experience, based on the configurations described above. The project researchers facilitated review sessions, consistent with steps 1 through 7 of the review process also previously described.

While the linguist, the psychologist, the specialist in measurement, and (obviously) the translator had English-language proficiency, teachers and curriculum experts on both committees had a limited knowledge of that language. One criterion which professional translators use for assessing the quality of a translation, is that any translated material should appear to have been written directly in the source language. Consequently, teachers’ and curriculum experts’ limited knowledge of the English language allowed their judgments on the items in Spanish to remain free of the influences exerted by an understanding of the items in the source language.

After the discussion of each item, the review committees agreed to classify the item as acceptable or questionable. This decision was made in a somewhat subjective, but collegial manner, based on the impact, in the reviewers’ judgment, that the quality of the translation could have on students’ performance. The reviewers were unaware of the procedure used to quantify the items’ translation errors.

III. Results

The lack of information about the students (e.g. external measures on their academic performance, demographic information or information on their linguistic or reading/writing skills) limited the range of analyses we were able to perform. Consequently, our study was limited to analyzing the frequency of translation errors observed among populations by grade and content area, and to the correlations between measurements of translation quality and p-values of the questions.

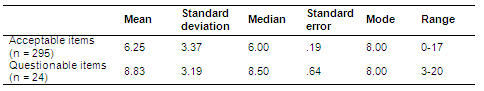

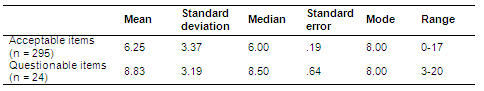

Frequency of translation errors. In most of the items there were found translation errors belonging to two or more dimensions. On an average, the items had errors in approximately four dimensions (mean = 3.84, S.D. = 1.68, median = 4.0, mode = 4.00). About 7.5% of the items analyzed were identified as unacceptable. These tended to have the highest error scores (Table II).

Table III. Number of Errors: Descriptive statistics

of items identified as acceptable and as questionable.

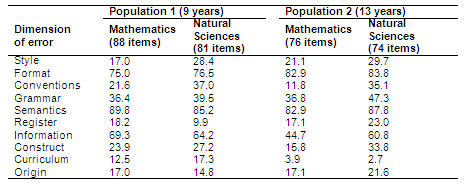

In general, we observed similar patterns of error frequency in both populations and in both content areas (Table III). For example, common mistakes observed in the items for Population 1 and Population 2, and in the items in mathematics and natural sciences come from the categories semantics (82.0%-89.8%) and format (75.0%-83.8%). However, significant differences were observed between populations and between content areas in certain dimensions. One of these was register, in which the frequencies were different between populations and between content areas within each population. Registry errors were more frequent in mathematics items (18.2%) than in natural science items (9.9%) for Population 1; but were more frequent in natural science items (23.0%) than in mathematics items (17.1%) for Population 2. Another case was curriculum. Errors in this dimension were much more frequent in questions used with Population 1 (12.5% and 17.3% for mathematics and natural science, respectively) than those used with Population 2 (3.9% and 2.7% for mathematics and natural science, respectively).

Table IV. Translation errors by population, content area

and size of dimension, in percentages of items.

Some differences in error frequencies came from influences on discursive styles that are more common in one content area than in another. Thus, in many mathematics items we saw an error that consisted in translating two sentences (for example, “Daniel buys four books that cost $23.50 pesos each. How much money does he need?”), as a single sentence in the grammatical conditional (“How much money does Daniel need it if he buys four books that cost $23.50 pesos each.”)

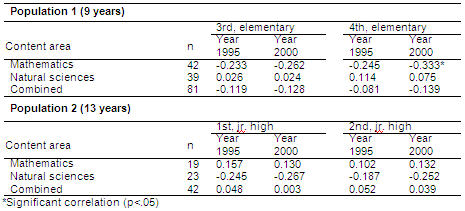

Correlation between translation quality and p-values. In interpreting the correlations of the error scores with p-values of the items, it should be borne in mind that it is not the same correlation as a cause-effect relationship. A high negative correlation simply suggests the possibility of a significant effect on the quality of translation in students’ performance. It is also important to note that poor translation is not always biased against the population examined in the target language (see Solano-Flores, Trumbull and Nelson-Barber, 2002, van de Vijver and Poortinga, 2005). For example, using a keyword more times than in the original language version can potentially skew an item for the population examined in the target language.

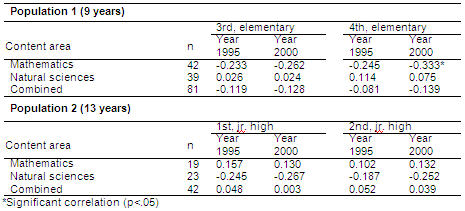

P-values of the items and the number of translation errors correlated differently depending on the population and the content area (Table IV). For Population 1, negative correlations were observed for positive items for mathematics and natural sciences. Population 2 showed the opposite pattern: negative correlations for natural science items, and positive ones for mathematics items. Although the vast majority of correlations are not significant, the patterns of correlations are consistent in both grades and in the two years of the test’s application. In both populations, negative correlations are consistently higher than positive correlations.

Table V. Pearson correlations (two-tailed) between the p-value of the item and the number of translation errors by population, content area and year of application.

Due to the lack of additional data, it is not possible to interpret these results in terms of the interaction between a faulty translation and the intrinsic linguistic demands of each content area. The differences in the directions of the correlations may be a mere effect of the different skill levels of those who translated the items of the two content areas or items applied to the two populations. However, this hypothesis cannot be tested due to lack of information on the translation process used for the items.

All we can conclude from the results obtained is that our procedure was sufficiently sensitive to translation errors to reveal systematic differences between items of different content areas and different populations, with respect to correlations between the items’ error measurements and their p-values.

IV. Concluding Remarks

Our knowledge of the sensitive issues involved in the translation of tests has increased over the past 10 years. For example, research in the field of international comparisons have shown that even a slightly inaccurate translation of a word can be enough to affect the differential operation of an item (Ericka, 1998). The procedures used in the translation of tests in international comparisons have evolved in accordance with that knowledge. For example, PISA and TIMMS now use two source languages as a strategy to ensure that the meaning is preserved in translation (Grisay, 2002). In addition, the use of back translation (re-translating the item back into the original language) is no longer accepted as irrefutable proof of equivalence between languages.

However, despite progress, the review of test translation has not received the same kind of attention; for example, the cultural aspects related to language are not always considered in a formal way. In addition, in the usual practice of test translation it is common to suppose that working with translators who are familiar with the culture of the population for whom the translation is destined, is a sufficient condition for addressing the main aspects of language use (see Behling and Law , 2000). However, as we have already discussed here, is not possible to identify translation errors related to the social aspects of language use, if one does not have a detailed coding system.

In this paper we have presented for reviewing the translation of tests, a conceptual framework which establishes error dimensions including, among other things, the use of language in social and instructional contexts. We have also described how it can facilitate test-translation review sessions in which multidisciplinary committees of reviewers discuss and code translation errors.

The results of our analysis of the items on the TIMSS-1995 test indicate that the approach is very sensitive to any type of error, from minor production and printing errors to errors in semantics and curricular representation. On an average, the items had translation errors belonging to approximately four dimensions of error. The most common mistakes were observed in the dimensions format and semantics.

Finding that almost all the items examined had errors of translation may be shocking at first. However, these high frequencies can be deceiving if they are not interpreted properly. First, we need to remember that error does not mean fatal error. Our qualification process is based on a deficit model, i.e., it is designed to detect faults, rather than simply deciding whether the items are acceptable or not. It is based on the assumption that perfect translation of a test is virtually impossible, and the assumption that it is the cumulative effect of many errors or the presence of critical errors, that makes the translation of an item questionable.

However, we believe that the observed frequencies of error are too high. One possible reason for this is obvious: the quality of the translation of the test was deficient, as demonstrated by the 24 items identified by the panels as severe cases of inadequate translation and which, for some inexplicable reason, passed through all the evaluative filters. Another reason is that our conceptual framework is more detailed, and considers aspects such as register and semantic translation from a more formal linguistic perspective.

It should be noted that the high frequency of errors detected, not only speaks of the quality of the Mexican translation of the test, but also of the need to revise the existing paradigms on test translation and the review of it. The Mexican version of the TIMSS-1995 went through a certification process based on standards used by the TIMSS office before it was accepted for use with Mexican students. A report on the quality of the data from the TIMSS-1995 includes a chapter on the procedures used to check the quality of translations of the test (Mullis, Kelly and Haley, 1996). It also provides the number of items identified as problematic in every country. According to the report, perhaps published at the same time that Mexico was withdrawing its participation, “none of the items used by Mexico had been identified as problematic.”

It would be unfair to attribute the inconsistency between that report and the results of our study entirely to the limitations of the guidelines for the test translation used at that time to coordinate the work of translation in the participating countries. In our opinion, given their general character, it is not reasonable to expect that those regulatory documents themselves should engender valid test translations, if the participating countries do not have rigorous internal-review procedures to ensure proper implementation of these guidelines. The fact that many details of the implementation of the TIMSS-1995 in Mexico have been destroyed and that there is no documentation of the process used in translating the test, is an indication suggesting that countries should develop mechanisms to ensure effective participation in international comparisons.

In conclusion, we offer four recommendations to countries interested in ensuring that their participation in international comparisons is grounded in valid test translations.

- Countries should allocate the qualified personnel necessary for an appropriate process of translation. The translation of tests should be done by teachers and professionals of different specialties working in teams, discussing in detail every aspect of the translation. In addition, the translation process should be coordinated by professionals who have a good knowledge of the test development process and by professionals in the field of linguistics.

- Countries should make sure that the activities of test review be an essential part of every stage of the process of test translation, not just the final phase. The adequate translation of a test must be understood as a process as thorough as developing a test in the original language. In that process, versions of the items must be perfected based on collegial discussion by the members of the review committees. These versions of the items should also be piloted with samples of students from the target population to ensure that interpretation is correct.

- Countries should make sure to allocate enough time for several iterations of test proofreading. A well-known problem regarding the validity of translated tests is the small amount of time allotted to the translation process. Limiting the time for the test’s translation also limits the possibility of discussion among translators and reviewers, and consequently, the ability to identify and solve translation problems.

- Countries should ensure that the teams in charge of the test translation and proofreading, document all their actions and justify all their decisions. Documenting the translation process is part of the standards of professional practice in the areas of measurement and evaluation (see American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, 1999). It also contributes to human-resource training in these areas, since it allows people involved in projects of international comparisons to learn from the experience of other colleagues.

We should not underestimate the importance of these recommendations. They deal with issues consistently identified as critical in the literature on the development, translation and adaptation of tests. For countries with a recent history of evaluation using standardized tests, and with a scarcity of professionals having formal training in the area of measurement, these aspects are particularly problematic. Dealing with them is crucial if we are to derive a substantial benefit from participating in international comparisons.

References

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association-National Council on Measurement in Education. (1999). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: Author.

American Translators Association. (2003). Framework for standard error marking and explanation. Retrieved October 10, 2003, from: http://www.atanet.org

Backhoff, E. and Solano-Flores, G. (2003). Tercer estudio internacional de Mathematics and Natural sciences (TIMSS): resultados de México en 1995 and 2000. (Col. Cuadernos de Investigación No. 4). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación.

Behling, O. and Law, K. S. (2000). Translating questionnaires and other research instruments: Problems and solutions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ercikan, K. (1998). Translation effects in international assessment. International Journal of Educational Research, 29, 543-553.

Greenfield, P. M. (1997). You can’t take it with you: Why ability assessments don’t cross cultures. American Psychologist, 52 (10), 1115-1124.

Grisay, A. (2002). Translation and cultural appropriateness of the test and survey material. In R. Adams and M. Wu (Eds.), PISA 2000 Technical Report (pp. 42-54). Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Hambleton, R.K. (1994). Guidelines for adapting educational and psychological tests: A progress report. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 10 (3), 229-244.

Hambleton, R. K. (2005). Issues, designs, and technical guidelines for adapting tests into multiple languages and cultures. In R. K. Hambleton, P. Merenda, & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment (pp. 3-38). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Maxwell, B. (1996). Translation and cultural adaptation of the survey instruments. In M. O. Martin & D.L. Kelly (Eds), Third International Mathematics and Science Studdy (TIMSS) Technical Report, Volume 1: Design and Development. Chestnut HILL, MA: Boston College.

Mullis, I.V.S., Kelly, D.L., & Haley, K. (1996). Translation verification procedures. In M.O. Martin and I.V.S. Mullis (Eds.), Third International Mathematics and Science Study: Quality assurance in data collection. Chestnut Hill, MA: Boston College. Retrieved October 10, 2003, from: http://timss.bc.edu/timss1995i/TIMSSPDF/QACHP1.PDF

O’Connor, K. M. and Malak, B. (2000). Translation and cultural adaptation of the timss instruments. In M. O. Martin, K. D.Gregory, & S. E. Stemler, (Eds.), TIMSS 1999 technical report (pp. 89-100). Chestnut Hill, MA: International Study Center, Boston College.

Solano-Flores, G. (en prensa). Successive test development. In C.R. Reynolds, R.W. Kamphaus and C. DiStefano (Eds.), Encyclopedia of psychological and educational testing: Clinical and psychoeducational applications. New York: Oxford University Press.

Solano-Flores, G. & Backhoff-Escudero, E. (2003). La traducción de pruebas en las comparaciones internacionales: un estudio preliminar (Technical report para el Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación). Mexico, DF: Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación.

Solano-Flores, G., Contreras-Niño, L. A., & Backhoff-Escudero, E. (Arpil 12-14, 2005). The Mexican translation of timss-95: Test translation lessons from a post-mortem study. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the National Council on Measurement in Education. Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Solano-Flores, G., Contreras-Niño, L. A., Backhoff-Escudero, E., & Andrade, E. (2006). Development and evaluation of software for test translation review sessions. Poster presented at the 5th Conference of the International Test Commission: Psychological and Educational Test Adaptation Across Languages and Cultures: Building Bridges Among People. Brussels, Belgium, July 6-8.

Solano-Flores, G. and Nelson-Barber, S. (2001). On the cultural validity of science assessments. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38 (5), 553-573.

Solano-Flores, G. and Trumbull, E. (2003). Examining language in context: The need for new research and practice paradigms in the testing of English-language learners. Educational Researcher, 32 (2), 3-13.

Solano-Flores, G., Trumbull, E., & Nelson-Barber, S. (2002). Concurrent development of dual language assessments: An alternative to translating tests for linguistic minorities. International Journal of Testing, 2 (2), 107-129.

Solano-Flores, G., Trumbull, E., and Kwon, M. (2003, 21-25 de abril). The metrics of linguistic complexity and the metrics of student performance in the testing of English language learners. Symposio presented en 2003 Annual Meeting de la American Evaluation Research Association. Chicago, IL.

Vijver, F. van de and Hambleton, R. J. (1996). Translating tests: Some practical guidelines. European Psychologist, 1, 89-99.

Vijver, F. van de & Poortinga, Y. H. (2005). Conceptual and methodological issues in adapting tests. In R. K. Hambleton, P. Merenda, & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment (pp. 39-63). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Translator: Lessie Evona York-Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

1Some portions of this article and ideas contained in it come from the authors’ presentation at the annual meeting of the National Council on Measurement in Education in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, in April of 2005; and from two presentations at the congress of the International Test Commission in Brussels, Belgium, in July of 2006. This research was funded by the National Institute for Educational Evaluation (INEE), through a collaboration agreement with the Autonomous University of Baja California. We thank Felipe Martinez-Rizo, Andre Rupp, Norma Larrazolo, Patricia Baron and Arturo Bouzas for their comments and observations on an earlier version of this work.

2The software was developed by Edgar Andrade of the National Institute for Educational Evaluation (INEE), Mexico.

Please cite the source as:

Solano-Flores, G., Contreras-Niño, L. A., & Backhoff-Escudero, E. (2006). Translation and adaptation of tests: Lessons learned and recommendations for countries participating in TIMSS, PISA and other International comparisons. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 8 (2). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol8no2/contents-solano2.html