Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 7, No. 2, 2005

University Outreach: The Dark

Object of Desire

Guillermo Campos Ríos

gcampos@siu.buap.mx

Facultad de Economía

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla

22 Poniente No. 1507, casa 5

Colonia Lázaro Cárdenas

Puebla, Puebla, México

Germán Sánchez Daza

sdaza@siu.buap.mx

Facultad de Economía

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla

Circuito Oriente 15

Colonia Unidad Guadalupe, 72560

Puebla, Puebla, México

(Received: September 6, 2004;

accepted for publishing: June 13, 2005)

Abstract

This article argues that the limited progress in outreach within Mexico’s higher education institutions (HEIs) is due to the lack of a clear and socially-shared meaning of what this activity is. We propose a typology based on the actions undertaken in the HEIs. This emphasizes the concept oriented by an economistic point of view. It also raises the possibility of recognizing outreach as a basic function in addition to those usually recognized in the HEIs.

Key words: Outreach programs, higher education.

Introduction

We employ for effect the title of Luis Buñuel’s famous film, “That Obscure Object of Desire” (1977), to propose that in university outreach there exists a metaphor similar to that which the film director sets forth in his work, and which, from our point of view, is the impossibility of achieving what we desire when the environment is marked by consumerism.

In the last ten years a link with society, specifically the manufacturing sector, has been one of the objects most desired by all Mexican universities. These have celebrated hundreds if not thousands of collaboration agreements, have created extensive and costly administrative structures to take charge of this function, have held forums, debates—and the balance, to date, is negative. The results are minimal; it would appear that there has been grasped only the shadow of the desired object.

Why is it that something so deeply desired has not been obtained? Apparently, in this circumstance as in many other similar ones, the sheer will to possess is not enough. The premise of this paper is that Mexican universities have embarked on “approaches” to the productive sector or to society, out of ignorance, especially theoretical, of the function of outreach.

It is very recent—the recognition within the universities themselves—that this is a function involving professionalization. The history of those who have worked in this area is only one step—almost always ephemeral—taken by the outreach management offices. They have spent decades in the repeated training of cadres in charge of this effort so that, at the end of one rector’s administration—or before—the cadres are replaced by new administrators who, in turn, resume the cyclical process of training and dismissal.

On the other hand, administratively, outreach management offices are located on the third or fourth level, and in many cases are under the authority of departments whose function has nothing to do with outreach activity.

There exists a university administration that impedes—right from the start—the development of outreach activity; however, this is not the only constraint, and certainly, is not the one on which we shall linger on this occasion; rather, we will occupy ourselves with that which serves as a premise for this article: the lack of a theory of outreach, and hence, the confusion of outreach with other activities, basically those of extension and the provision of services.

The failure of higher education’s outreach is not a problem unique to Mexico. The same process or the same behavior is found at least in the countries of Latin America. Here are some of the results detected in several regions by two who have studied them, Arocena and Sutz (2001):

In Brazil, 8.3% of the companies surveyed stated that engagement with the university was important for developing and achieving innovations; however, universities are the option mentioned least often as a source of ideas for innovation [...] On the other hand, in Mexico, cooperation agreements for innovative projects reached only 6% of the businesses surveyed [...] At the same time, in Venezuela, engagements with universities are at 3.5%...while in Chile, 25% of businesses say they have entered into contracts with universities; of these, the ones reporting a medium or high incidence of signing contracts with universities constitute 3.7% of the total (Arocena and Sutz, 2001).

In this same study, the authors point out that in Argentina, the universities were cited as enablers of innovation ideas for just over 4% of the companies in the sample, and in Uruguay, counseling agencies under contract to public technological bodies reached 27.2% of the enterprises in 1987, with the University of the Republic providing 10% of the total (ibid).

The establishment of outreach between Latin American universities and their respective production environments is a task pending performance. There exists strong evidence that it is beginning, but not to the extent desired by those who follow only the American model, in which some universities operate with high budgets derived from their relationship with companies or foundations.

The vague concept of outreach

At present there is little likelihood of establishing a single definition of the role of outreach in the universities, first because when an attempt has been made to come up with a definition, it has been in very general terms: furthermore, around this function there revolves controversy over two aspects:

- In the historical sense, mainly related to the time of its origin.

- In terms of concepts, in confronting various forms and approaches to understanding what outreach is.

However, in all the positions, the idea prevails that outreach always refers to the relationships that exist—or should exist—between the university and the society of which it is a part. Additionally, there is another shared aspect: to consider outreach as axiologically positive, as a desirable function or an element of “virtue” in institutions of higher education.

In connection with the historical, there are two proposals. One, the more traditional, considers that outreach has existed since the emergence of today’s university. From this point of view, outreach has characteristics constant over time and space. Thus, outreach would be a homogeneous concept, and valid for any university at any time, and the problems of its implementation would consist in simply making some adjustments required by specific conditions.

The other position assumes that outreach must be understood as a historical process defined by the social conditions of each era. Thus, one would expect there to be different models, defined in each case both by the historical moment, and by the specific circumstances of each institution.

There are a great number of articles and books which review the experience of outreach in American or European universities; however, their processes are so radically different from what has happened in Mexico that it does not seem sensible to take these experiences as role models for outreach strategies that could be imagined for our country. However, we frequently hear statements that orient outreach activities toward following the American model.

So as not to increase confusion over what could be understood by outreach in a country like Mexico, and in circumstances of profound change in the universities, we will not restrict ourselves to the texts produced by Mexican researchers who have systematically addressed this issue.

Giacomo Bei Gould argues that outreach, or engagement, has formed part of the field of higher education for more than a century, although in many countries—says the author—the former classist universities for a long time resisted the creation of “outreach.” The origin of the contemporary university, and hence, of outreach, would be at the end of the nineteenth century (Bei Gould, 1997).

In the Autonomous University of Puebla, statements have also been made about the time considered to be the genesis of outreach activity; this corresponds to the stage indicated by Bei Gould:

When in 1910 Justo Sierra introduced the idea that academic education should not remain indifferent to the country’s social needs and problems, the reaching out by higher education and research to the society was established as one of the university’s basic principles. Since then, what made higher education institutions acquire one of their most important commitments was contributing their resources toward national development (Moreno, 1998, pp. 25).

There is another group of researchers who emphasize the socio-historical sense of engagement, sometimes manifested by the existence of historical stages which define this function. Among these researchers we can mention Rebeca de Gortari, who asserts the existence of two organizational revolutions that have given rise to two different models of outreach (1994):

To approach it from an institutional perspective, the proposal of Etzkowitz and Webster (1991) establishes the distinction between two key moments in the engagement between the university and society: that of the first revolution, which took place in the nineteenth century, when research was integrated into the universities as another of its primary duties; and of the second, which we are now experiencing, and which means that universities must assume new financial responsibilities toward society, in addition to the former ones of offering education and carrying out research. This way of approaching outreach allows a focus on the changes that have occurred in university organizational structures, and on the values of the different actors involved [...] Hence, to assume this new role, higher education institutions, in the seventies and especially in the eighties, began a period of policy and strategy formulation that allowed them to interact differently with the productive sector (De Gortari, 1994, pp. 40).

Regarding the proposal of the existence of historical periods that determine outreach, we also find Carlos Payán (1978), former director of the National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education (ANUIES, its Spanish acronym), who traces the origin of outreach in Mexico to the twentieth-century decade of the seventies, together with the beginning of a policy of research at our country’s universities. Payán associates the possibility of outreach only to the extent that there is a minimum level of research development. In other words, there can be no real outreach if there is no raw material to exchange, which, in this case, would be precisely the research results. But in addition, these results would have to possess a certain degree of development and applicability. This is a very attractive consideration, since Payán concluded that it would have been in the early 1990s when the possibility of a relationship between the productive sector and the university would have become a truly viable function. Therefore, up to that time, outreach could be described as practically nonexistent, or as an activity in process of formation. To this author, outreach is a process which at that time was passing through a further phase of its construction. The present would be a stage just emerging as a new need for the institutions of higher education—would be a very novel kind of additional function.

There is a line of research whose followers have raised some concerns that outreach is really a new feature of the modern university, and not a sub-function derived from established foundational activities. These scholars clustered themselves around Leonel Corona and a group of doctoral researchers on Technological Economics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM, its acronym in Spanish). They hold inter alia that:

Due to the increasing convergence between scientific research and technological development, one of the functions of universities, that of producing knowledge, must take on meanings also new (...) In reality, there is required an effort that includes government action, by agents and actors of the productive sectors and by what is called the science and technology system. Although the outreach process itself is desirable, it is not easy to define or implement (Crown, 1994, p. 123).

Something interesting to note among the Leonel Corona group’s proposals is that they locate the concept of outreach in the sense of “agency”; that is, while it may be important to the role of certain individuals in particular, more important is the impact which the institutional actors may have, when joined into a network that, together, might solve the problem of outreach through advances in research.

Other differences, rather conceptual, are the following differentiated positions:

- Those who believe that outreach has a basically economic content.

- Those who believe that outreach is resolved exclusively through a physical approach to society (physicalist view, which is also strongly associated with an assistential view).

- Those who believe that outreach is a new fundamental role for universities.

The economistic vision

Among those with this perspective on outreach we find those who believe that universities, through the sale of their products and services, will gain juicy morsels of financial resources. It has not yet been possible to find an official document that states this position with total clarity. However, university officials and administrators in general, support it directly.

This proposal is widely published, although little formalized and documented. It is reinforced in this era of budget cuts, because it creates the hope of using it as leverage to get support for the universities in the midst of financial crisis. Outreach is basically seen as selling services.

This is a somewhat idyllic view, since empirical evidence suggests that even in cases of our country’s more developed universities, such as the UNAM and the Metropolitan-Iztapalapa Autonomous University, with a highly-consolidated research base, where engagement with the industrial and public sectors has resulted in the crystallization of important agreements and consulting contracts, the resources it contributes still represent small percentages of their total budgets.

In reference to this, Matilde Luna (1997) states:

Given that the possibility of funding derivable from outreach has not resolved, significantly, the economic problems of the universities, (...) the principal motive for outreach focuses on the different purposes and dynamics (of companies and universities), as well as on changes in economic policy and the need for public universities to legitimize their existence and demonstrate their relevance in society (p. 243).

As we can see from the above quotation, the economistic perspective would be only a part of what outreach really means. Without denying this alternative, it should clearly be complemented by other types of objectives.

Into this same conceptual schematic can be incorporated the proposal which the Industrial Research Team of the Autonomous University of Puebla has managed under the name “productivist aspect” (Campos and Sánchez Daza, 1999), but which is in essence a form of the economistic view.

The productivist perspective—also widespread, although not fully recognized—understands outreach as valid only when carried out by the productive sector of the economy, and more specifically, the industrial structure. This is the most controversial perspective, because it is associated with a very common university practice.

We can see that what is called outreach in the context of education and production has been used strictly to identify a set of activities and services which institutions of research and higher education conduct to address technological problems of the productive sector. In this sense, outreach points to a technology-transfer process that may involve building bridges between scientific research and technological development to address environmental problems (Casas and De Gortari, 1997, pp. 171).

With the outreach model that prevails in the UNAM, since 1983 there has been a search by means of the creation of the General Directorate of Technological Development, “to promote inside and outside the University, the connection between scientists and technical staff of the UNAM, and the productive sectors” (Casas and De Gortari, 1997, p. 164). This directorate was replaced in 1984 by the Center for Technological Innovation (CTI), whose aim was to build a more structured and organized liaison between the university and the productive sector. Following the CTI, there have been initiatives such as Nuclear Networks of Technological Innovation, whose objective is to carry out transfer activities conducted through the researchers themselves; in cases that merit this, small technology-transfer units are set up within each unit.

Besides this, the UNAM has created other institutions such as the Morelos Technological Park, between the Electric Power Research Institute and the Manufacturers Association of Morelos, as a place where technology-based companies can find an environment conducive to the development of their activities. In 1992 there was established the Business Incubator System for Science and Technology, with the aim of promoting and creating entrepreneurs. It is currently closed.

Approximately 30 institutions of higher education were represented at the International Seminar on Enterprise and Incubator Programs, held on the campus of the Autonomous State University of Morelos in May, 2004. There it was noted that approximately 10% of these institutions either have, or are developing a business incubator project (Noticias sobre actividades académicas, 2004). However, the results and advances are either poorly disseminated or are scarce. In fact, most of the most successful empirical experiences are oriented toward this productivist view.

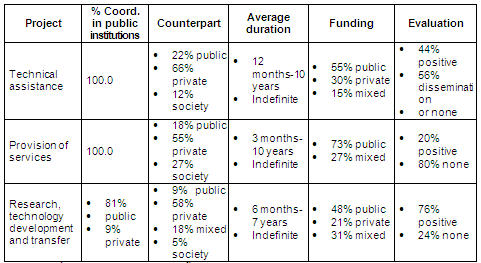

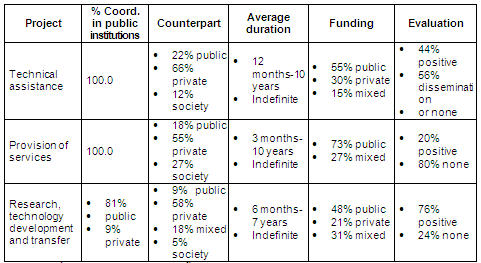

Some of the results of outreach activities that have been made public through the ANUIES report for the first half of the nineties, are 210 successful cases, of which 180 were Mexican and 30 American, and that were directed toward the following activities: a) technical assistance; b) provision of services and c) research; technology development and transfer.

Table I. Result de outreach activities in Mexican universities, according to the ANUIES

The presence of public institutions is central in promoting and conducting research; however, in all cases it is private institutions that take advantage of the results. Outreach, in this Mexican experience, is paid for by public funds.

The average project duration is totally uncontrolled, since it ranges from a few months to 10 years, and some projects are described as being of an indefinite length. This lack of control over the research process results in difficulty in controlling outreach.

There is no existing culture of evaluation for research projects, nor for outreach. Hence, opinions as to the final results emitted by users are vague.

As shown, there is a view that finds its arguments in the production structure. While it is not considered that this view is the one that would exhaust the notion of outreach, it can indeed be seen that there are a number of efforts and endeavors in play, in favor of this type of rapprochement between the university and its environment. At any rate, apparently this notion of outreach is not being successfully carried out either.

It is important to note that the level of research development will be the major bottleneck in implementing a productivist-type engagement. To make outreach viable, it is not only necessary to do research in the university laboratory, but it is also essential that it be possible to transfer the results of that research as technology.

The physicalist view

According to this method, outreach is verified, almost exclusively, to the extent that material (physical) distances between university and society are shortened, so that from this point of view, almost anything can be recognized as outreach: from installing a dentist’s office in a poor neighborhood, to the presentation of a play, or the development of distance-learning programs, or the training of human resources at a factory, or the transfer of technology. This perspective makes it almost impossible to distinguish the activities that could actually fall, today, within a modern definition of outreach.

This view flourished especially in the 1970’s, when recognition of education’s popular character strengthened the guidelines supported by a strong assistentialism toward economically and socially disadvantaged sectors. In most of its expressions university extension came to be confused with outreach, and was also unavoidably linked with assistance proposals.

Furthermore, the physicalist view could be considered as the most traditional, and the one that has created greater misunderstandings about outreach. However, it is still common to find it as part of the activities allocated to outreach offices, confusing them with simple areas of university extension.

Outreach as a new university function

Up till now it has been argued that universities have three basic functions: teaching, research and extension. However, it is increasingly necessary to expand the horizon of functions to include outreach. It was after the 1984 UNAM Work Report that there was raised the possibility of understanding outreach as a new function, and not as part of university extension. Since then, this concept has seemed to acquire more scope. Now it is considered a structural axis of academic planning. In other words, the functions of university teaching and research find mechanisms and forms of organization connecting them ever more closely and effectively with society and the economy, while conserving the character of assistance that prevailed before.

This change also means the establishment of a new social contract between academia and society—a contract which requires broad, strong government support, in proportion to the role assigned to research in the new economic model. The adoption of this new contract and its translation and implementation will vary, obviously, from one institution to another and will depend largely upon the response and support of national and international policies.

In some of the views presented earlier, there is perceived the need to consider outreach as a new university function or activity. This cannot be resolved by adopting models similar to those employed in North American or European institutions, because in Mexico the relationship between educational institutions and the productive sector has been radically different from that in other countries.

Outreach is a feature that allows universities to realign their goals and visions for the future, while keeping their feet on the ground and continuing to be recognized as a part of society. Universities are aided by identifying themselves as institutions interested in helping to solve the problems facing the citizens of the regions where they are located, or of society in general.

This new vision of outreach is much more complex, and is linked with structures of institutional support which, at the same time, see with other eyes the activities of teaching and research.

Developing outreach] actually requires an effort that includes government actions, agents and actors from the productive sectors, and the so-called science and technology system. Although the outreach process itself is desirable, it is not easy to define or implement (Corona, 1994, p. 132).

Like the rest of the university functions, outreach should be integrated into everyday academic life, and should be resolved collectively. The outreach offices only assume the role of “facilitators” of this activity, which day by day the teachers and researchers of each school or research center cultivate and consolidate.

This new proposal also includes critical aspects such as:

a) including the evaluation of outreach itself;

b) engagement not only with the exterior, but above all, with the interior of the university.

It is essential to promote internal liaison as a start-up phase in global projects with foreign connections. The outreach area must earn an academic leadership, and must generate moral confidence between university students, so as to permit new forms of communication between students and academia; between schools, research centers and the students themselves

Conclusions

The lack of a unified theory of outreach has restricted the progress of this type of activity in Mexican universities.

Outreach can be understood as a new fundamental role of universities. Consequently, these are forced to build “action networks” that extend beyond the university itself; that is, they must include a program closely related to other agents, such as government, production entities, the educational system as a whole, and above all, upper-level research centers, and even sections of society that can contribute—in a truly operational structure—to building the broader frameworks of outreach. This, of course, does not involve subordinating the action of university outreach to prospective agreements emanating from a structure as large as the one described.

There exists the possibility of creating an outreach strategy which, to make it more effective would adopt—at least in the beginning—a profile characterized by its regional and sectoral orientation.

The adoption of outreach as another of the basic functions of universities involves building a framework for clear and relevant evaluation of the results.

The development of outreach will depend on advances in research activities, especially in terms of turning out products that can be transferred successfully to society or the productive sector.

References

Arocena, R. & Sutz, J. (2001). La universidad latinoamericana del futuro. Buenos Aires: UDUAL.

Buñuel, L. (Director). (1977). Ese oscuro objeto del deseo [movie]. France. Greenwich Film Production.

Campos, M. Á. & Sánchez Daza, G. (1999). La vinculación, tarea incumplida por las universidades. (Mimeographed document). Puebla: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Facultad de Economía.

Casas, R. & De Gortari, R. (1997). La vinculación en la UNAM: hacia una nueva cultura académica basada en la empresarialidad. In R. Casas & M. Luna (Coords.), Gobierno, academia y empresas en México. Hacia una nueva configuración de relaciones (pp. 163-227). Mexico: Plaza & Valdés-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Corona, L. (1994). La universidad ante la innovación tecnológica. In M. Á. Campos & L. Corona (Coords.), Universidad y vinculación. Nuevos retos y viejos problemas (pp. 123-138). Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

De Gortari, R. (1994). La vinculación, parte de las políticas universitarias. In M. Á. Campos & L. Corona (Coords.), Universidad y vinculación: Nuevos retos y viejos problemas (pp. 31-44). Mexico: Instituto de Investigaciones en Matemáticas Aplicadas y en Sistemas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Gould, G. (1997). Vinculación universidad-sector productivo. Una reflexión sobre la planeación y operación de programas de vinculación. Mexico: Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior-Universidad Autónoma de Baja California.

Luna, M. (1997). Panorama de la vinculación en la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM). In R. Casas & M. Luna (Coords.), Gobierno, academia y empresas en México. Hacia una nueva configuración de relaciones (pp. 229-246). Mexico: Plaza & Valdés-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Moreno, R. (August, 1998). Pasado, presente y futuro del servicio social en la BUAP. Revista Gaceta Universidad, 9 [New period], pp. 22-28.

Noticias sobre actividades académicas (May-June, 2004). Gaceta de Economía (Facultad de Economía de la Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla), 4.

Payán, C. (1978). Bases para la administración de la educación superior en América Latina. El caso de México. Mexico: INAP.

Sanchez, M. D., Claffey, J. M., & Castañeda, M. (1996). Vinculación entre los sectores académico y productivo en México y los Estados Unidos. Catálogo de casos. Mexico: Asociación Nacional de Universidades e Instituciones de Educación Superior.

Translator: Lessie Evona York-Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

Please cite the source as:

Campos, G. & Sánchez Daza, G. (2005). University outreach: That obscure object of desire. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 7 (2). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.ens.uabc.mx/vol7no2/contents-campos.html