Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 7, No. 2, 2005

Initial Education for Immigrants’ Children

in Spain’s “Welcoming Schools”

María del Pilar Quicios García

pquicios@edu.uned.es

Departamento de Teoría de la Educación y

Pedagogía Social, Facultad de Educación

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia

C/ Senda del Rey 7, Despacho 225, 28040

Madrid, España

Isabel Miranda Vizuete

L.VELA@grupobbva.com

Colegio Nuestra Señora de las Delicias

Paseo de las Delicias, nº 67

28045 Madrid, España

(Received: April 5, 2005;

accepted for publishing: May 24, 2005)

Abstract

This article describes the initial training received by immigrants’ children arriving in Spanish schools. It also shows the reality they encounter during their first months of schooling. These students have three hallmarks: ignorance of the Spanish language or a low level of understanding; curricular lag of more than two academic years; or no previous schooling in their countries of origin. Aiming to palliate these deficiencies, and to offer these children some guarantee of success in their studies, the administration’s Board of Education has decided to enroll them temporarily in a series of classrooms designed specifically for them: the “Welcoming Schools”. These classrooms are an innovative educational answer launched in January, 2003, and now beginning to bear fruit.

Keywords: Initial education, immigrants’ children, lag in curriculum, Welcoming Schools.

Introduction

The Welcoming Classrooms are a pioneering experiment, launched in Madrid under the Fundamental Law 10/2002 of December 23, concerning the Quality of Education, which aims to integrate students from other latitudes into the Spanish school system, with guarantees of academic success in the medium and long term. These classrooms are designed to serve the children of immigrants who come to the school in total ignorance of Spanish, or with a language level so low that it precludes considering their Spanish as a vehicular language, with a total absence or deficient process of prior schooling in their country of origin and a curricular lag of over two academic years as related to the knowledge acquired by students enrolled in Spain in the level of reference.

It is hoped that from these classrooms will be received, admitted and integrated into the country’s educational system, the flood of non-native students who arrive at the Spanish school all during the year, since migratory phenomena occur equally at all seasons, and have little or nothing to do with the official school calendar.

The experience gained in the last decade in Spain has shown that it was urgently necessary to apply some measure of attention to diversity, which could admit these students at any time of year. That measure was the creation of specific classrooms for them; the welcoming classrooms. Indeed, enrollment in these welcoming schools is a privilege.

These class groups are programmed for second and third-grade elementary-school students from (i.e., pupils from 8 to 12 years old) and compulsory high-school students (12 to 18 years). Students under 8 are personally taught in their regular classrooms by the tutors and professionals who make up the Educational Orientation and Psychopedagogy Teams (EOEP’s) serving the various schools in their zones.

In the welcoming classrooms there is no attempt to compensate for differences in origin, nor to support the acquisition of knowledge through various techniques or methodologies, nor to reinforce a particular area or run a personalized adaptation of the curriculum. Here, the endeavor is broader: to introduce students to the academic or instructional world, as well as to train them attitudinally, socially and culturally, although the process begins from the purely academic setting of the school.

Currently, this work is carried out by the teacher assigned to such classes, usually a professional who specializes in teaching Spanish as the mother tongue, or who has adequate training and experience in teaching Spanish as a second language. Theoretically, this teacher, in turn, must have experience in other fields related to the training of immigrant students and students with remedial-education needs. The reality, however, is that the administration also allows these positions to be filled by teachers specializing in foreign languages, or even by those having no specific expertise.

These classrooms are the starting point for the initial training of foreign students in Spain’s culture and educational system. Due to the great importance they will have in shaping this segment of the school population, these classrooms should be run by the professionals most competent, qualified, motivated and sensitive to the initial training of such students. Up to now, this has not happened, but it is certain that after some years of experience the situation will be reconsidered and the ideal profile of professionals to carry out this task will be sought.

The Welcoming Schools as part of the Spanish educational system

Spain’s Fundamental Law of Education (LOCE), as now in force, develops in its Section 2 (“On foreign students”) the educational attention outlined by the Ministry of Education, and applicable to foreign students attending school. The instructions provided are summed up as five guidance points of intervention in Article 42 ("Incorporation into the educational system"). In these five points it is interesting to note the first three paragraphs:

- The educational administrations will encourage the incorporation into the education system of students from foreign countries, especially those of compulsory school age. For students who do not know the Spanish language and culture, or who present grave lacks of basic knowledge, the educational administrations will develop specific learning programs, in order to facilitate the integration of these students into the proper level.

- The programs referred to in the preceding paragraph may be provided, in accordance with the planning of the education authorities, in specific classrooms established in centers which give instruction in the ordinary regime. The development of these programs will be simultaneous with the education of pupils in the mainstream groups, according to the level and evolution of their learning.

- Students over the age of fifteen, and who have serious problems in adapting to compulsory high school education may enter the vocational training programs established by this Act (Law 10/2002, December 23, on the Quality of Education, Section 2, Article 42).

As may be deduced from reading the Act, the liaison classrooms or welcoming schools, as these initial-training sections are also called, do not constitute any concrete stage in the Spanish education system; rather, they represent temporary and collateral groupings. At the same time they can be considered another modality of programs for attention to diversity, existing in all areas of the country. These specific classrooms accept immigrant students within their walls for a maximum period of six months, the length of time which educational theorists consider necessary and sufficient for them to reach a level allowing these foreign students to be then integrated into the ordinary classroom, or the same school—if the center has vacancies so as to accept them—or in another school assigned by the School Commission, taking into account the nearness their family residences.

Two weaknesses have already been shown in this initial training of the immigrant student. On the one hand, it limits the time spent in specific classrooms to a period of six consecutive months, over one or two academic years after the incorporation of students into the classroom. On the other hand, there is the possibility that the student cannot continue her schooling in the same school where she has been accepted, and must re-adapt to the educational system in another school. Theory and practice, praxis and theory, once again, must be faced. From the theory of education these two weaknesses of the welcoming schools do not exist, and if they did exist, they would not harm the student, since if the classroom has fulfilled its role, the student will have acquired the necessary level to be integrated, with guarantees for success, into any ordinary classroom of any school in the country.

Educational praxis reveals that it is impossible to predict the exact time it will require a student to become integrated into an educational system different from his own. There will be a set of variables that must be weighed to achieve a successful initial training, such as: the culture that comes from the language he uses, his level of previous instruction, the curricular competency he presents. Without taking these variables into account it is impossible to make an accurate delimitation of the time needed for a student to receive an initial training that will allow him to be incorporated with guarantees of success into an educational system that is foreign to him.

It is proposed that the incorporation of the immigrant student into a regular classroom will be produced both by the teaching team in the liaison classroom, and by the teaching team in the regular classroom in which he is going to be enrolled. These educational teams will evaluate, independently, for sufficient language and instrumental skills, as well as the student’s adaptation to the behavioral norms established in the school community. They will then issue a final report which they will submit to the educational inspection body, which will in turn, evaluate and report the result. If based on this assessment the process is considered to have been completed successfully, the immigrant pupil will be permanently enrolled in a regular classroom of any school. In the event that the process of cultural immersion has failed or is being produced more slowly than originally foreseen, there could be granted an extension of the stay the liaison classroom.

If, in spite of this possible but exceptional extension, the student should have used up the time provided for his stay in the liaison classroom without having managed to reach the established goals, he would then be considered a special-needs student, and would therefore receive specific attention from the Educational Orientation and Psychopedagogical Team (if he is enrolled in primary education) or the from the Guidance Team (if enrolled in high school), following in all cases the established protocol for attention to diversity in the Spanish educational system.

As stated here, the importance of the initial training received in this type of classroom has been sufficiently demonstrated. On the effectiveness of his management and on the evaluation of his performance will depend whether the immigrant student is enrolled in regular classrooms as one more student of the education system, and can continue his schooling successfully, or whether he will be considered, based on the way he has started out in this educational system, as an individual excluded from mainstream education and as a recipient of special educational measures, compensatory education, special education, etc.

Objectives of initial training in the welcoming classroom

The Ministry of Education identifies the guidelines or objectives to be pursued in the initial training offered in the liaison classrooms so as to integrate the immigrant student into the education system. Following the general instructions given by the Deputy Ministry of Education for the 2003-2004 academic year (Ministry of Education, Directorate of the West Madrid Territorial Area, n.d.), the objectives are, roughly:

- To enable the provision of specific attention to foreign students with no knowledge of Spanish, or those who have a serious curriculum problem, to be incorporated into schools during the school year.

- To support the acquisition of language and communication competencies, and to develop the process of teaching and learning through appropriate curricular adaptations.

- Facilitate the inclusion of the student and to abbreviate her process of integration into the Spanish educational system.

- To encourage the development of the student’s personal and cultural identity.

- To achieve the integration of these students into the school and social environment in the shortest time under the best conditions.

More precisely, in the classroom programming of these welcoming schools these objectives have been specified as follows:

a) General objectives of initial training in the liaison classroom:

- To provide the student with the communication skills that will allow her to relate with her social environment and participate normally in the school setting.

- To facilitate integration into the reference group in the shortest time possible.

- To develop in her the use of strategies and schemes of knowledge as a way of achieving greater personal autonomy and effectiveness in learning.

- To link students with the reality of Spanish society, and to promote closer cultural contact stemming from attitudes of respect.

b) Specific objectives of the initial training in the liaison classroom

The specific objectives are basically two. One is purely conceptual: the learning of Spanish as the vehicular language for further training within Spain’s educational system. The other is attitudinal, i.e., peer interaction with an eye to achieving the social integration of the immigrant student in a real way.

The teaching of Spanish as the vehicular language in the liaison classroom will have as an objective the development in the immigrant students of the following capabilities:

- Understand general and specific information of verbal messages issued by teachers, peers and other Spanish adults.

- Use the information received for the specific purposes for which it was issued.

- Understand general and specific information in written messages, based on texts dealing with situations familiar to students.

- Produce oral and written messages in Spanish, following the rules of interpersonal communication with an attitude of respect toward others.

- Produce simple oral and written texts related to their interests and needs, in which they respect the rules of the oral and written language system.

- Recognize and appreciate the value of learning Spanish as a communication vehicle and as a sign of respect for its speakers and culture.

- Recognize and use linguistic and non-linguistic conventions employed in the most common situations of oral interaction.

- Use knowledge and experience of the mother tongue as well as other languages they may know to promote independent learning.

Peer interaction in the liaison classroom will have as its objective to develop in the immigrant students the following capabilities:

- Use various strategies to compensate for failures in communication.

- Recognize the sounds, rhythm and intonation of Spanish, and establish relationships between these and their graphic representation.

- Use any type of linguistic or non-linguistic expression resource in order to understand and be understood in Spanish.

- Value group learning and the role of the teacher and peers.

- Reflect on the new linguistic system as a facilitator for learning Spanish, and as an instrument for improving linguistic production.

- Appreciate the wealth inherent in the existence of different languages and cultures.

- Develop a receptive and critical attitude toward information proceeding from the Spanish culture, using it to reflect on the culture of origin.

These objectives, attitudes and skills require a array of contents from which an educational structure can be created and take shape.

Content of initial training in the liaison classrooms

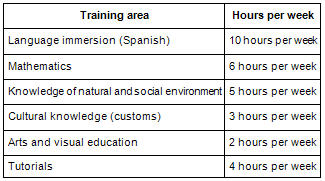

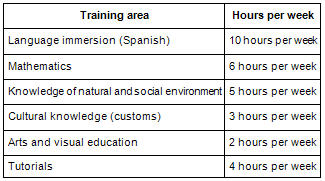

The contents are embraced within concepts, procedures and attitudes. This knowledge is developed in the training areas described in Table I.

Table I. Training areas and time devoted

In each of these areas there is developed a series of specific training strategies and teaching skills such as the following:

Language immersion, usually for 10 hours per week, during the first two hours of the morning, constitutes an effort to develop the students’ linguistic/communicative competency, focusing on productive skills (writing and oral language) and interpretation (reading and listening.) In this area, work is done on two different levels. The first is targeted toward students with no knowledge of Spanish. These pupils will work on personal identification, greetings; school, family, friends, city and district; games, sports, clothes and shopping; the body and its care, etc.

The second level is aimed at Spanish-speaking students with a curricular lag of two or more years as related to the contents studied in Spain by students of the same chronological age. For these students, listening and reading activities concerning topics close to their centers of interest will be selected, and it is proposed that learners write essays on aspects they have studied in the classroom in order to facilitate their ability to remember what they have studied.

In mathematics, for six hours per week (1¼ hour per day), each student receives individual tutoring, since these learners come from different nations and have different levels of learning. This is an authentic class of meaningful learning and of personalized learning pace, where a homogeneous, ordinary class would make no sense.

In environmental and social studies, five hours per week, usually given at the end of the school day, students enrolled in liaison classrooms receive training in the specific vocabulary of each of the study areas. In natural sciences they study the skeleton and muscular system, nutrition, the senses and the nervous system, human reproduction, animals and their classification, plants and so on.

In the area of social science they study the earth in the universe; the natural landscape, its topography, coasts and rivers, Earth’s climates, topography, hydrography of Spain, its territorial and political organization, historical periods, the most significant milestones, etc. In civics, in the unit on purchases, they learn to distinguish between shopping center, supermarket, market, sales gallery, flea market, store, stand, stall, and garage sale.

In cultural awareness, for three hours per week, using as a pretext the common symbols of this country (guitar, sun, food, bullfighting, flamenco, fans) and the cultural and training routes of the city of Madrid, there are shown Spanish customs, habits of behavior, relationships between young people, family celebrations, birthdays, weddings, children’s parties. In all this it is always stressed that knowing the customs of the host country's society does not mean giving up the manifestations of their own culture, but rather, learning about other cultures and other customs allows them to value and develop more, if they wish, their own culture and customs.

In tutoring sessions (four hours per week) an effort is made to strike a balance with the rest of the school program, and to know the emotional state of each student who, because he is an immigrant in a strange land, brings together the griefs resulting from his status as a pre-teen or teenager. This time of life, as Prof. Estela Flores-Ramos says, is “a chronological stage which brings them face to face with essential griefs which might be the loss of childhood, the relationship with their parents and the physical changes in their bodies” (Quicios, 2005, p. 99). For these boys and girls, says the author, the grief resulting from the loss of key references is harder, if possible, because the decision to emigrate from their countries of origin was not made by themselves; rather, they have had to accept the decision of their parents, who, moved by the need to find a better quality of life, have had to seek an opportunity for advancement. Their immigrant families have in many cases been marked by the suffering caused by their illegal status. Moreover, their unemployment plight tends to subject them to harsh living conditions and economic deprivation. Finding themselves in such a situation in the host country’s society weighs on the minds and souls of these children and young people. It affects the way they are, at school and in life in general (Quicios, 2005).

While interest is shown in the state of mind and the emotional status of the students, they are informed about Spain’s education system and standards of living, the role of the social and intercultural mediators in municipal councils, the importance of training in the values predominating in the host country’s society, the importance of human rights. These sessions present only one problem: that of oral communication, since they are conducted in Spanish, and sometimes students do not understand. In these cases the teacher turns to students of the same nationality, if there are any in the classroom; these classmates help to translate for those who cannot follow the development of the class because they do not understand the language.

If such potential translators are available, or in the absence of them, in both cases the teacher falls back on pictograms with the 30 most common action verbs in Spanish, which she has prepared using a 10 x 12 cm. format, or on laminated cards, 10 x 12 cm. and 8 x 7 cm. These show animals, plants, food, body parts, clothing, household utensils, types of scenery, and so on.

In short, all of the intended training needs to have a strong dialogic and communicative base of Spanish. This is not usually seen in the liaison classrooms, since in them there may be are up to 12 different languages. But this is very difficult to provide.

It has been observed that a new weakness has presented itself in the liaison classrooms and in the initial training of this collective, a weakness that could be overcome if the liaison classrooms were created in accordance with nationalities, or at least, with language. This would be easy, because not all schools have liaison classrooms.

Location of liaison classrooms

As we stated previously, not all schools have liaison classrooms. The Ministry of Education selects a network of centers in the capital and the province where these welcoming schools are located, according to criteria such as:

- Express acceptance of the proposed program by the school which will implement and execute it.

- Schools with adequate spaces available.

- Express commitment by the school to enroll the students coming from liaison classrooms in regular classes, once they complete their initial training

- The school should be located in neighborhoods or towns with high concentrations of non-indigenous population.

- The facility should have prior experience working with students from other cultures, and who have a partial or total ignorance of Spanish.

- The school must have a dining room, an open-door program, extension plans for cultural and extracurricular activities, availability of sports and cultural facilities in vacation and holiday periods.

- Set the proportionality of schools in urban zones and in rural zones, as well as between teaching levels (primary and secondary schools).

One way to augment the efficacy of these classrooms would be to group students schooled in them homogeneously. Such homogenization could be carried out by focusing on their mother tongue. In no way does this mean building ghettos and segregated schools, but rather, optimizing the process of integrating this population into the education system. The work is not difficult to implement because, as shown in the Spanish National Statistics Institute’s report on foreign population, July 2003: “Immigrant populations are spread throughout the country, and are grouped primarily by nationality and culture” (p. 7).

Setting up liaison classrooms serving the dominant nationalities of their students would reduce some problems that occur in these classrooms today, such as:

- The existence of several cultures in the same space, which implies many standards of behavior and habits very different among themselves, and also quite remote from the standard in Spain.

- Different instructional levels as a result of previous schooling conducted in their countries of origin.

- Additions staggered throughout the school year depending on the country they come from and the academic calendar followed there.

- Lack of material resources in the classroom to meet the educational demand of students of different nationalities.

- Treatment of scholastic absenteeism, justification of absences.

Another fundamental problem that would be solved is that of oral communication with students in Spanish. If liaison classrooms were set up by dominant languages—given the limited number of classrooms spread over the autonomous community—it would not be audacious to suggest that the teachers in charge of these classrooms should have at least some notions of their students’ native language.

A new weakness could be overcome: the homogenization of social and civic education that should be offered in the classroom. It would be much easier and fruitful to work on unfamiliar values, customs, habits and behaviors with students all belonging, not to different cultures, but to the same culture predominating in the classroom.

The reality currently existing in the liaison classrooms makes it very difficult to standardize students immersed in a multicultural environment, students who have to assume values and norms very distant from their natural habits, in order to develop their future life in the clearly-multicultural Spanish society.

A third difficulty would be settled by having classrooms homogeneous by nationality. The instruction which each student should receive could be designed effectively, because his previous study plan would be fully known by the liaison-classroom teacher. Thus, it would impact on exactly those issues that have shortcomings in regard to the Spanish curriculum, and indeed, the knowledge of these students could be evened out.

Human Resources

The liaison classrooms are directed by up to two regular teachers who, theoretically, have had some previous experience in the teaching of Spanish. One teacher is the group’s tutor. It is easily understandable that this is not the right profile for the teacher of such specific classrooms. To be sure, these professionals have received a minimum of initial training given by the Department of Attention to Diversity, but because their training has been very limited, they are in no way qualified to develop the enormous work expected of them. This training has consisted of a process divided into two phases: on the one hand, previous training developed over 25 lecture hours and given in the Teaching Service Centers (CAP’s) for the entire Community of Madrid. On the other, there has been designed a second phase for deepening and strengthening the above. In the first part of the course the teachers who will lead these classes learn the legal regulations that will guide both their activity and the function of these groups; develop strategies and acquire resources for teaching Spanish as the vehicular language; and learn to make adaptations to the curriculum that will allow students to be integrated into the school.

In the second phase of the course, teachers are shown programs for schooling immigrant children in Europe and models of joint community-education initiatives for attention to students coming from families of immigrant origin. This is the sum total of the knowledge they acquire. With this initial training, teachers are sent off into liaison classrooms. Although it is true that these professionals can count on the punctual support of specialized counseling teams from the school’s orientation teams and from external services such as the Municipal Translation Service (SETI) and the Immigrant Support Service (UPS), everything else depends on the teachers themselves. With their training, professionalism, experience, empathy and good work, they must overcome the daily challenges, and respond to the functions which the regulations stipulate as requirements for teachers in these classrooms.

These functions are related to teaching, mentoring, monitoring and evaluation of the students assigned to them. Thus, teachers must:

- Develop the classroom curriculum, adapting it to the characteristics of students and the needs of the center.

- Plan, in collaboration with the Office of Studies, the organization of school hours for students in the liaison classroom.

- Address the difficulties of student learning.

- Work together with the parents/guardians in the students’ reference groups.

- Facilitate the integration of students into the group, school and society, potentiating their skills and encouraging their participation in school and community activities.

- Promote student participation in free-time and leisure activities.

- Maintain communication with families, informing them of progress and the possibilities they have in the Spanish educational system.

- Conduct ongoing evaluation of student’ learning and progress; assess the proper moment for incorporating students into regular classrooms.

- Make an individualized report for each student; this will be part of the learner’s academic record. It will report the outcome of the teaching and learning, knowledge and the educational guidelines considered necessary.

- Prepare the final course report, in which are recorded the number of students served, an assessment of compliance with the objectives, and an evaluation of the actions carried out.

Knowing the professional competencies of Spanish teachers, educators and social workers, it is clear that the functions asked of liaison-classroom teachers are far removed from their teaching work. Optimization of the results of these classrooms would help to adapt the profile of the professionals serving in them to the competencies required at all times. The teaching staff of these classrooms should be made up of a pedagogical specialist, a social educator and a teacher.

Only by harmonizing competencies and requirements can the results of the initial training be optimized, and can proper attention be given to immigrants’ children who have been torn away from their symbols of identity, their countries of reference and their educational systems, and who have been brought by force into environments unknown to them and in some cases, even hostile.

Not caring for these students in the way they deserve is to condemn the immigrant population, by default, to scholastic failure, and by extension, to the lower echelons of the Spanish labor market—an objective totally opposed to that which has moved them to search in Spain for a place where they can improve their quality of life.

References

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2003). La población extranjera en España (Report). Madrid: Author. Retrieved March 12, 2005, from: http://www.seg-social.es/imserso/migracion/pobextranjeraesp.pdf

Consejería de Educación, Dirección del Área Territorial de Madrid Oeste. (s.f.). Instrucciones generales de la Viseconsejería de Educación para el curso 2003-2004. Retrieved March 13, 2005 from: http://www.madrid.org/dat_oeste/a_enlace/ae_instrucciones.htm

Quicios García, M. del P. (Coord.). (2005). Población inmigrante: su integración en la sociedad española (una visión desde la Educación). Madrid: Pearson Educación.

Legislative references

Ley Orgánica 10/2002 de 23 de diciembre de Calidad de la Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, No. 307 (December 24, 2002).

Translator: Lessie Evona York-Weatherman

UABC Mexicali

Please cite the source as:

Quicios, M. del P. & Miranda, I. (2005). Initial education for immigrants’ children in Spain’s “welcoming schools”. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 7 (2). Retrieved month day, year, from: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol7no2/contents-quicios.html