Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa

Vol. 7, No. 1, 2005

A Social Development Assessment Scale

for Mexican Children

Rocío Aguiar Sierra

raguiar@prodigy.net.mx

Instituto Tecnológico de Mérida

Calle 41 No. 173, Col. Benito Juárez Norte

Mérida, Yucatán, México

Pedro Antonio Sánchez Escobedo

psanchez@tunku.uady.mx

Facultad de Educación

Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán

Apartado Postal 1207, C.P. 97000

Mérida, Yucatán, México

David J. Satterly

djsatterly@hotmail.com

Graduate School of Education

University of Bristol

Bristol, United Kingdom BS8 1JA

(Received: September 27, 2004;

accepted for publishing: February 23, 2005)

Abstract

This work described the design of an instrument able to measure social development for Mexican children and the process of the establishment of its psychometric properties. Theoretical aspects considered for its construction and the process of validating forms for parents and teachers are described in a three stage processes that resulted in a final version of the Social Development Scale that measures, disruptive behavior, social interaction, cooperation, acceptance and attachment as core dimensions associated with the concept of social competence. The importance of assessing social development and competence for education, children rearing and general well being are analyzed and discussed.

Key words: Social development, early interpersonal relationships.

Introduction

Developing the appropriate social skills depends upon various influences during childhood. Success in adult life is often related to the development of skills needed to adapt to a variety of social settings. Thus, it is important to measure social skills at an early age. Social development refers to the set of behaviors that a child displays in situations that involve others. The term is used with reference to the ability to make and sustain relationships, which relate to social adjustment and acceptance within the peer culture. In addition, there is an intra psychological component which includes feelings related to social situations such as the sensation of being accepted by others, as well as the thoughts and judgments of the person, such as the awareness of one’s social status.

I. Purpose

The purpose of the study is to construct and validate an instrument to measure basic social skills of Mexican children. It is intended to detect children with delays in social development at an age as early as 4 years. It is expected that teachers, psychologists, and other professionals can use such an instrument to appraise indicators useful to measure change over time or the impact of appropriate programs.

II. Objectives

- To construct a scale of social development appropriate for 4 years old Mexican children

- To establish its reliability, validity, and norms.

III. Importance of the study

After a thorough search for instruments used in pre-school settings and of recent research related to the area, one can conclude that in Mexico, there is a lack of systematic assessment procedures and scales useful for the detection of children with poor social adjustment. This fact hinders the possibility of early intervention to prevent future problems. In fact, in most Latin-American countries, the majority of strategies used to detect delays in social development are intuitive, clinical and unsystematic. Furthermore, no specific scales were found currently in use in Mexican schools to assess children’s social development.

The majority of available instruments are translations of popular scales from the United States. Measures of social development are commonly reported as scores in specific subscales of more general psychological development batteries, for example the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (Sparrow, Balla & Cicchetti, 1984).

Furthermore, there is a lack of instruments that take into account specific cultural factors involved in the phrasing of the items included in the instrument. Thus, the evaluation of social development risks the biases of clinical appraisal or the biases of the cultural differences embedded in instruments devised elsewhere.

Culturally appropriate scales are necessary since the way parents relate to children, the amount of freedom allowed, the expectations they have, among other events differ r from one culture to another. Consequently standards of social adjustment vary with the cultural norms by which they are judged (García Coll & Magnuson, 1988). Appropriate assessment devices, therefore, must abide with cultural norms and this appears to be a very important factor in assessing the child’s scholastic potential.

IV. The importance of assessing social development

Traditionally, developmental psychologists have attempted to describe behaviors across different life stages in order to establish group norms against which one could compare growth, maturity or the presentation of expected milestones. Furthermore, studies in this field try to explain why behaviors occur, how they can be modified, the degree in which they can predict future adult behavior, all of the above with the intention to learn how to foster a healthy psychological development (Stone & Church, 1979; Seifert & Hoffnung, 1997).

The origins of social behavior can be observed in very young children. Different types of studies have analyzed the early foundations of social interactions: sensitivity to others, differentiation of self from others, interactions with mothers, responsiveness to siblings (Dunn & Hendrick, 1982; Waters, Wippman & Sroufe, 1979; McCoy, Brody & Stoneman, 1994).

Accepting the current need to evaluate social development in pre-school children requires conceiving social development in a more complex perspective that includes behaviors, feelings and thoughts, this requires appropriate strategies to measure and evaluate a child’s social development.

When analyzing child’s social development, in addition to estimating the quality and quantity of peer interaction, one must also consider the thoughts and feelings of the social players. That is, one must take into account the judgments and thoughts of others toward a particular child, and the feelings and thoughts of that particular child toward others.

Indeed, authors such as Pellegrini & Glickman (1991) and Green, Forehand, Beck & Vosk (1980) have argued that information to assess social development should be obtained not only from direct observations of target behaviors, but from information given by parents, care takers, teachers and others in contact with the child. In addition, it demands the development of valid and reliable instruments that are pertinent to the theoretical stand taken, and are also adequate for the target population.

In sum, the recent interest of scholars in social development has led to the consensus that its evaluation in early years might be as useful as assessing cognitive development (for example reading or writing) in the preschool years. However, to adequately measure social development one must possess valid and reliable scales.

V. Developing social competence

From birth, interactive responses emerge and transform into more complex social interactions. During the first year infants can distinguish and react appropriately to emotional expressions of caregivers. According to Haviland & Lelwica (1987), social behaviors such as gesturing and touching increase from six to twelve months.

Dund and Kendrick (1982), reported that in their second year children show helpful and cooperative behavior and empathetic responses to the distress of others. The forms of social interactions after two years of age become increasingly varied. Children at this age show different degrees of social awareness, cooperative play, understanding the feelings of others and social norms.

By the age of three children can marshal some very sophisticated reasoning about social relationships. Children understand the connection between their own actions and the other person’s state of pain, anger or amusement. Their power of understanding and knowledge of social rules may be used in struggles to get their own way. By the end of the third year children not only recognize what others want but they grasp the idea that sharing is often expected from them (Dund and Kendrick, 1982).

According to Harris and Gross (1988) by four years of age children are taking into account the desires of others in predicting their emotional state. At this age children are also involved in social exchange, and sharing with their friends and peers is usually a very well mastered norm. Indeed, Strayer (1986) asserted that children at this age are more interpersonally oriented.

At this stage it also seems more likely that the child has had the opportunity to be involved in enough social interactions and would have mastered the required social skills to interact with peers and others. On the other hand at the age of four it is still early enough to detect and prevent any possible difficulty in social development. Also, it is more likely that the child would be involved in academic programs through which his/her social development could be monitored.

5.1. Factors influencing early social development

The development of social skills, this is the behavior that leads the child to solve social tasks and achieve social success, will enable the child to engage and sustain social interactions and will result in the acquisition of certain degree of social competence.

Hartup (1989) regards this ability to develop social competence as one of the most important developmental tasks in early childhood. The development of social competence has been related to later adjustment and academic achievement. In fact, Wentzel (1991) asserts that social competence in childhood is a powerful predictor of academic achievement. On the other hand, Coie & Dodge (1988) stated that children who develop appropriate social skills are less likely to display current and future problems of adjustment. Only by understanding the nature of the developmental process is it possible to understand the links between early adaptation and later disorders (Sanchez, 1986).

Research has found some important factors that could influence early social development, such as parenting style, attachment, and siblings.

Firstly, Dishion (1990) found a relation between the family ecology and the rejection or acceptance by peers. Pettit, Dodge & Brown (1988) have stressed the importance of considering the family relationship factors to develop social competence in children. Baumrind (1971) analyzed the effects of different parenting styles on children’s social interactions. During preschool years the parenting style is an important issue, since it would affect the child social abilities. Children at this age usually test the limits their parents impose on their behavior. They have a strong desire to control their own environment. The way their parents respond to this is important. Parents tend to have different beliefs and styles of parenting. Understanding the parents’ style of authority will lead us to understand the child’s way of relating to others.

Baumrind (1971) analyzed how parenting styles influence children’s behavior. She found that children of authoritative parents tend to be self-reliant, self-controlled, and able to get along well with their peers. These children tend to have a higher degree of psychosocial maturity. On the other hand, children of authoritarian parents tend to have poorer peer relations and poorer school adjustment.

Secondly, the child’s experiences with the parents and the extent to which parents have been reliable and predictable in their care and accessibility in the past, determines the quality of another important factor, attachment.

The quality of attachment would determine the child’s willingness to engage and benefit from social interactions. The basis for trust in relationships with others would develop from early attachments. If the child has a secure attachment, it is more likely that s/he would be willing to interact with others outside the family. Secure attachment also favors exploratory behaviors, which would also increase the likelihood of social interactions.

The most compelling evidence that the quality of the child’s social development is a reflection of the underlying quality of the parent-child relationship has been explained by Bowlby (1969) attachment theory. Even when Bowlby’s theory has been strongly criticized by feminist researchers we cannot deny its influence in this area of study.

According to Bowlby (1969) the development of attachment goes through four phases. At first, the baby would show no specific interest in his/hers parents. But, the infant’s behavior would have some influence on the adults around it. From three to seven months the infant would start showing preference for those who are gratifying. It is after seven months that parents become important. First attachments are formed at this stage. This stage will end at 30 months, when the child will start the goal corrected partnerships.

Ainsworth (1979), identified three different types of attachment (secure, avoidance, resitent o ambivalent) each of them leading to different types of behavior in the children. Secure attachment (Ainsworth & Bolwby, 1991) leads to a child able to feel fine when the parents leave, but also show interest or satisfaction when they return. This will allow the child to engage in other activities when the parents are not around without any fear or rejection to the parents when they return.

More evidence of the importance of attachment in the development of social skills is found in different studies. Waters et al. (1979) concluded that the quality of attachment would predict competence and acceptance in the peer group. Lamb (1978) mentioned that attachment is important in three ways: a) the infant’s trust in its parents can be generalized to others; b) securely attached infants are willing to become actively engaged with other aspects of the environment, maximizing the benefit from extensive social experiences; c) children would be more likely to interact with their parents without fear or weariness. Lieberman (1977) found that the social competence of the children was related to the quality of the attachment between mother and children, and the amount of experience that the child had had with peers. Lieberman, Doyle & Markiewics (1999) found that father availability was related to children having less conflict with their friends.

Inconsistent or rejecting parents are more likely to create insecure attachments and this could have deleterious consequences for children’s social relationships with peers (Cohn, 1990).

One of the most important characteristics of mothers of competent children is that they interact sensitively with their children. They also experience pleasure in these interactions. Stone & Church (1979) suggested that children who grow up in supportive environments are likely to be better adjusted.

And thirdly, if parents are important agents of socialization so are siblings. The great majority of children have at least one sibling. Interactions with siblings contribute to develop the child’s understanding of the needs and feelings of others. According to Azmitia & Hesser (1993) siblings are considered agents of cognitive and social development. Siblings spend a significant amount of time together. The positive quality of their interactions and the high degree of mutual imitation suggests that they enjoy each others company and are interested in each other’s behavior. Hartup (1989) believes that the mismatch between their competencies encourages the acquisition of skills. Children’s experiences with siblings provide a context in which interaction patterns and understanding skills may generalize to relationships with other children (McCoy et al., 1994).

As these studies report the family as a whole contributes to the social and cognitive development of the child and his/her entrance to the peer group. The early social development of the child will be the result, as has been mentioned, of the combination of many factors such as parenting styles, early attachments and interactions with siblings. All of these variables together with the child’s personality and the specific settings where he/she is expected to interact with others will have a tremendous impact on his/her early social development.

VI. Assessing early social development

Green et al. (1980) found in their research evidence the importance of assessing children’s social competence from four different perspectives: peers, teacher, the child and objective behavior measures. Pelligri and Glickman (1991) in comparison accept the importance of assessing social competence with peer nominations, behavioral measures and teachers ratings but instead of the child’s own assessment they show preference for standardized testing.

There are various methods of assessing social development, qualitative and quantitative, standardized, clinical and ethnographic. For example, in a qualitative view, a common method of obtaining a measure of peer acceptance is the peer nomination technique. In this technique children are asked to nominate a specified number of classmates according to certain criteria. This approach had its roots in the work of Moreno (1934) who believed that interpersonal relationships and experiences should be understood via consideration of two fundamental aspects of interpersonal experience: attraction and repulsion.

From a quantitative perspective, Brofenbrenner (1989) made some methodological advances so that by the late 1950’s researchers had developed an index of child’s status in the peer group (low status, high status and average).

Even projective techniques have been used to evaluate social skills: for example Perry (1979) developed a conceptualization of the sociometric status in preschool children. Using a modified picture questionnaire he classified children into four categories: popular (high social impact - positive social preference); rejected (high social impact - negative social preference); amiable (low social impact - positive social preference); isolated (low social impact - negative social preference).

Following Perry, several new sociometrical classification taxonomies were developed. According to Rubin, Bukowski & Parker (1998) the most frequently used is the one developed by Coie, Dodge & Coppotelli (1982). The labels he used were: a) popular, children who received many positive nominations and few negative; b) rejected, children who received few positive nominations and many negative; c) neglected, few positive and negative nominations; d) average, children who received an average of positive and negative nominations; e) controversial, children who received many positive and negative nominations.

Classifying children into the rejected status has been found both a reliable and a valid means of identifying children at risk (DeRosier, Kupersmidt & Patterson, 1994).

A modification of the peer nomination technique is adapted for preschoolers by Asher, Singleton, Tinsley & Hymel (1979), in order to increase the reliability of this technique. They use a Likert-type scale to rate each classmate according to some specified criteria.

Recent research indicates the importance of distinguishing between sociometrically rejected and sociometrically neglected children. Coie et al. (1982) indicate that rejected children exhibit more serious adjustment problems in childhood and in later life. A method for identifying neglected children is a combination of the positive nomination technique and rating scale measures (Asher & Dodge, 1986).

Despite the various approaches to assess social skills, in this study an eclectic approach is to be taken, in an attempt to develop a standardized instrument. The age of the children is one factor that strongly influenced this decision. Relationships at the age of four are short-lasting, therefore, the sociometric method would not bring any valid information. Projective techniques, on the other hand, have to be used by an expert, which is not the intention of this study.

For the reasons mentioned above, a checklist directed to record observable behaviors is to be constructed as a basis for the instrument to be developed. In fact, one checklist will be directed to parents for them to report their observations about the child’s social behavior at home and another will be directed to teachers to report the child’s behavior at school.

VII. Method

7.1. Purpose of the study

The purpose of the study was to construct and validate a preliminary version of an instrument to measure basic social skills of 4 years old Mexican children in the state of Yucatán. It is expected that teachers, psychologists and other professionals can use such instrument to appraise indicators of social development when attempting to detect children with delays in this specific domain. Furthermore, the instrument should also be useful to measure change over time and the impact of appropriate intervention.

7.2. Subjects

The instrument is intended for 4 years old Mexican children with the following characteristics and limitations for future generalization: Children are from the urban areas of the Yucatán attending a day care center, from lower to middle social class sectors, with both parents at work. For this study, the exclusion criteria were the presence of an obvious disability and obvious medical conditions affecting their social development.

7.3. Design and development of the instrument

In order to design the final version of the Early Social Development Measurement (ESDM), three preliminary versions of the instruments were developed during the course of the study to select appropriate items and establish their psychometric properties. Procedures carried out will be depicted in this section, as well as the mechanism for their construction and revision. The aim of this section is to provide the reader with the sequence, process and changes during the construction of the instrument. Likewise, information on participating subjects in each stage will be included as indicated in the previous section.

VIII. Stage I: Initial checklists

The researcher and her advisors found that no theoretical model revised was comprehensive enough and satisfactory to sustain the development of the scale for Mexican children. Thus, it was decided that a collection of frequently quoted behaviors, indicative of social development in the literature, were to constitute the initial database for the process. The start point was then, a list of items related to observable and measurable behaviors frequently quoted in the literature to describe 4 years old children. No importance was given to whether such statements depicted adequate or inadequate social conduct. Actually, the list was based largely on research identifying elements of social competence in young children and on studies in which the behavior of children well-liked by their peers has been found to be different when compared to that of those less well-liked children (Coie et al., 1982, Putallaz, 1983).

The initial work was also directed to decide who were to provide information about the children. Teachers, parents and peers have been mentioned in the literature as possible fundamental informants. Achenbach, McCanaughy & Howell (1987) reported that the correlation between reports of children’s behavior between different types of informants under different situations is much lower than similar informants in similar conditions. That is, parents and teachers observe the child in different contexts.

Parents, as well, seem to be natural informants due to their daily interactions with the child. Arguably, the inclusion of the parents perspective is often made under the assumption that they are able to observe the same type of behaviors as the teachers but in a different context, and provide information that the teacher would not be able to observe.

At this initial stage, the main purpose of the study was to determine whether items were culturally appropriate for the target population and if wording and grammatical construction of items was clear, unequivocal and easy to understand. For this purpose, two checklists were initially developed using the 40 items originally selected. Depending upon their context specificity and targeted behaviors, 36 items were included in the parents checklist whereas 33 items constituted the teachers’ list.

The initial checklists use a yes/no/beginning to, pointscale. The checklists were divided, for organizational purposes, into two sections: “Interaction with adults” and “Interaction with other children”. Under “Interaction with adults” there were 10 items in both checklists, and under “Interaction with other children” there were 26 in the parent’ checklist, and 23 in the teacher’s checklist.

For this initial stage, as it is recommended by the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Association, 1999), it was decided to invite a group of six experts to revise the checklists. Participants subjects were two pre-school teachers, two child psychologists and two sets of parents of 4 years old children. Professionals have a minimum of 5 years of experience working with four-year-olds. In general, suggestions were made regarding the response scale, the use and number of items and their clarity, as follows:

- To use a five point Likert-type response scale and rephrase some items so they could be answered with such a scale.

- To eliminate some items contained in others. For example: ”shows interest in other children” was contained in “plays with other children”.

- To balance both subscales by including an equal number of items in each.

- The cultural relevance of the items was stressed and the importance of the inclusion of items such as “spends the night over at grandparents” and “likes to invite friends to his/her house” was emphasized.

- The wording on two items was modified to enhance their clarity.

- Information on whether to use one or the two checklists was unavailable.

Therefore, the researcher decided to continue using both scales and leave the decision for the next stage.

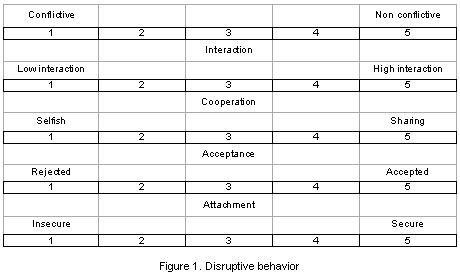

IX. Stage II. Modified version of the instrument

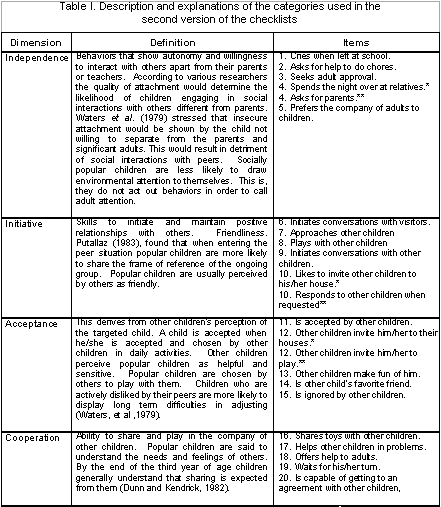

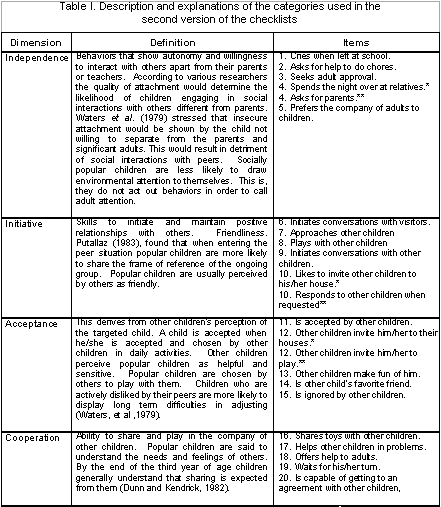

As a result of the first stage, a modified version was elaborated using 25 items for each checklist and a five point Lickert scale. The original division based upon the interaction with adults or peers was changed clustering items in five subdivisions of five items each, with the purpose of having a better presentation and an initial idea of what dimensions of social behaviors could be measured with this instrument. For testing purposes, five areas were established a-priori- considering both the results of the first stage and the advisors comments: Independence, Initiative, Acceptance, Cooperation and Conflict resolution. Of course it was expected to test empirically the five conceptual dimensions for assessing social development. Furthermore, this second instrument had 23 items that could be observed in both home and school settings. Only two items were different for parents and teachers (see Table I). Additionally, in order to enrich the information for the study, demographic data about the family was required in the checklist for parents.

Table I depicts the pre-established dimensions and its theoretical support, and the items included in this modified version.

For this stage it was decided to use a conventional sample of 30 children attending any of the 19 different day care centers affiliated with the Mexican Institute of Social Security in the city of Mérida.

Statistical analyses were carried out to determine Pearson’s correlation between the teacher’s and the parent’s evaluation of the same child in order to decide the usefulness of both checklists. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was considerably low (0.20). In addition responses for parents and teachers were analyzed individually and as a group. When approaching individual cases in seven of them (23%), differences in scores were higher than 10 points. In 30 cases (66%) the differences were less than 10 points, whereas only in three cases (10%) were the scores exactly the same between parents and teachers. However, when approaching differences as groups there were no statistical differences for the mean of parents 74.37 (SD 7.15) and for the mean of teachers 73.23 (SD 7.49).

Considering the above, a decision was made to use both scales in the assessment of the child’s social behavior under the tenant that a more comprehensive picture of it was to be obtained from two qualitatively different social settings: home and school. Furthermore, some important modifications were made in terms of the content of the checklists:

- To contemplate behaviors that could be observed in both contexts (home, school), items were substituted by others which were similar to the extent that the same checklist was to be used with parents and teachers in this final version.

- The labels for the five subdivisions of the checklist were removed since they may be misleading and give an appraisal of the child’s behavior as a general area (such as independence) rather than responding to each specific item. These categories were to be used at the end as a way of analyzing the information. At this point it was decided to let the factor analysis to determine the best way to arrange the different categories or areas of behavior in the checklist for the final profile.

X. Final instrument

Validation of the scale was carried out using the checklist resulting from previous stages. As described before, this was a single list to be administered to both parents and teachers. The checklists for parents and teachers had differences in the wording of some items to guarantee context specificity. For example, items such as “When adults visit home (or school)” were different for parents or teachers. Nonetheless, it was assumed they were measuring the same behavior shown by the same child in different contexts. The checklists contained 25 items without any grouping or subdivision. To record the answers again five-point Likert scale was used.

The target population were children enrolled in a day care center in the city of Mérida in September of 1999 (the beginning of the school year in Mexico). Since age was a controlled variable, targeted groups were those groups called maternal 3. These groups were made up of children who were to become 4 years old during the school year, in other words, during the period between September 1999 and August 2000.

In total, there were 512 children enrolled in all 19 day care centers at the beginning of the school year. A conventional sampling method was used again, by simply assessing children within two weeks of their birthday until the quota was filled. Parents consent was required for the children to be part of the study. To establish sample size, the following formula was used:

N = Z2pqN/ Z2pq + (e2) (N – 1)

The sample size was established at 154 children. This estimate provided a reliability of 90% and a standard error of 0.5%.

Of the 154 children assessed, 82 (53%) were boys and 72 (47%) were girls. All of them were almost exactly 4 years old. Fifty-five (39%) were the only child in the family. Sixty-one (43%) of the children had only a brother or a sister, with the same probability of this sibling being older or younger than the targeted child. In 45% of the cases the siblings were no more than two years older or two years younger than the participant child. Only 38 (18%) had more than one sibling.

At the time of data collection, the majority of parents were married (84%), 5% were divorced, 5% separated, and 6% were unmarried single mothers.

Regarding parental education, 8 (5%) of the mothers had at least a bachelor’s degree, in contrast, fathers had at least a bachelor’s degree in 36 cases (24%). Both parents were working when the instrument was applied (this is a requisite for admitting the child to the day care center). Parents were more likely to be employed in clerical jobs and one third of the mothers were secretaries.

Children were selected from the lists of attendance and a calendar was elaborated to determine the day of the most feasible administration of checklists. The principal investigator visited the school within a two week period prior to the child’s birthday and administered the checklist to the teacher. Once having the information from the teacher, she proceeded to give the parents’ checklist to the director of the center, who in turn, arranged for the parents to complete the form in her office. Parents usually responded to the instrument when they collected their child. Completed instruments were retrieved two or three days later. In four cases though, information from parents was lost in the process. Regarding data from parents, in the majority of cases (92%) only one parent responded to the instrument, usually the mother (86% of cases).

XI. Results

Means were compared for teachers and parents using a t-test for independent samples, which showed statistically significant differences between the scores (t = -3.20; P = > 0.002).

Parents and teachers views were rather inconsistent as showed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the scales (r =0.26, p = 0.005). Therefore, it can be inferred that although both scales measured the same phenomenon, by using both there is an additive effect that weighs the evaluation of teachers and parents, and adds more information than any one scale used alone. Therefore, it was decided to use scores from both scales combined and evaluate their psychometric properties.

Total scale is calculated by adding both totals (parents and teachers), and dividing the results by two. As such, the mean for the sample was 74.43 (sd = 7.96).

The Crombach Alpha coefficient was calculated for both parents (a = 0.44) and teachers (a = 0.54). Individual scales showed a relatively low internal reliability perhaps because of the different factors related to social development.

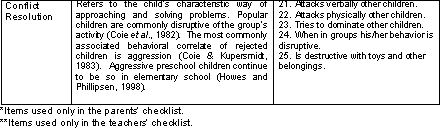

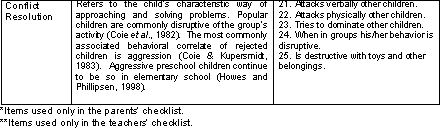

In order to explore the construct validity of the instrument a factor analysis test with a varimax rotation was carried out with the following conditions:

- An average from both parents and teachers was used as an item response estimate, since it has been previously demonstrated that this is a pondered estimate of the two.

- Items were converted in a yes/no scale by marking no (1, 2 & 3) and yes (4, 5). Table II illustrates factors yielded after the analysis.

he mean for the inter item correlation in both scales was around .06 . This rather null coeficcient leads us to consider that it is not possible to predict the answer to one item based upon the answer to another item. Results from analyzing the correlation between an item in one checklist and the same item in the other checklist are presented in the followin

The analysis yielded seven factors, three of which clustered five items each. By examining their contents the following proposed labels can be suggested for future research.

11.1. Factor I: Disruptive behavior

This factor relates to negative behaviors that usually create conflict with other children and are mainly violations of other children’s rights. Aggressive behavior towards others underlies this factor. The items considered to measure this factor are:

- Attacks physically other children.

- Is disruptive when interacting in a group situation.

- Attacks verbally other children.

- Tries to dominate friends.

- Is destructive with toys and other objects.

The item “Seeks approval from adults”, although it was described as part of this factor, due to its lack of relation to the other items used in this factor was not considered for the results as part of this factor.

11.2. Factor II: Interaction

This factor relates to daily expected social interaction with other children and adults. Play and communication skills are important components of this dimension. In this factor the following items were considered:

- Starts conversations with other children.

- Approaches other children.

- Plays with other children.

- Responds to questions asked by other children.

- Talks to adults that visit school/home.

11.3. Factor III: Cooperation

This factor relates to a very desirable pattern of behaviors in the Mexican society, and relates to help and cooperation. This is also a factor that measures desirable social abilities.

The items considered in this factor were:

- Offers help to teacher/parents.

- Can get to an agreement with other children.

- Helps other children in need.

- Shares toys with other children.

- Waits for his/her turn.

Although the item “Other children invite him/her to play” was also included as part of this factor it was not considered since it relates to other people perception of the child, and not cooperative behaviors like the other items in this factor.

11.4. Factor IV and VI: Social acceptance

These factors measure the degree to which the child is accepted by other children. Since the intention of questions in both factors relate to the same set of behaviors, it was surprising that they generated two different and apparently independent factors. Future studies should investigate the composition of this proposed dimension. However, since the sense and purpose of items seem to be alike, these factors are merged in the final version of the instrument into one single factor. The items included in this resulting factor would be:

- Other children make fun of him/her.

- Prefers to be with adults rather than with other children.

- Is the favorite friend of another child.

- Is ignored by other children.

- Is rejected by other children.

11.5. Factor V: Attachment

This factor seems to measure problems with attachment, commonly seen in day care centers. Children with secure attachments, as explained before, are expected to be more independent and to separate easily from parents. This behavior leads to a greater opportunity for interactions and an increased likelihood of not being afraid of others. From the items analyzed, only two were found to be related to this factor. However, because of the importance of the attachment element mentioned by authors such as Bowlby (1969), Waters, Wippman & Sroufe (1979), Ainsworth (1964) and others, more items were included in this compenent until it is composed of five items. Three additional and new items were added to the two items resulting from the analysis.

- Cries when left at school.

- Asks for parents.

- Seems afraid of being abandoned.

- Shows difficulties to separate from parents in parties and parks.

- Seems relaxed when left with other adults.

11.6. Factor VII

This factor is constituted only by one item related specifically to relations with adults, particularly demanding help from them. This item/factor was removed from the final version.

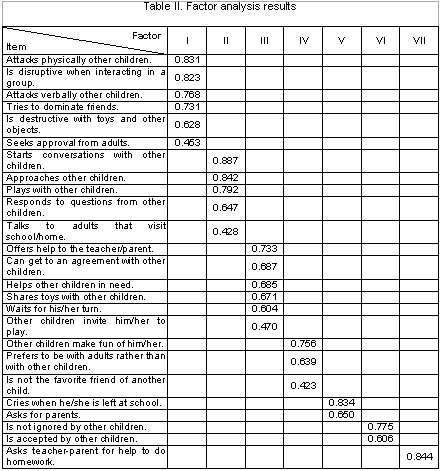

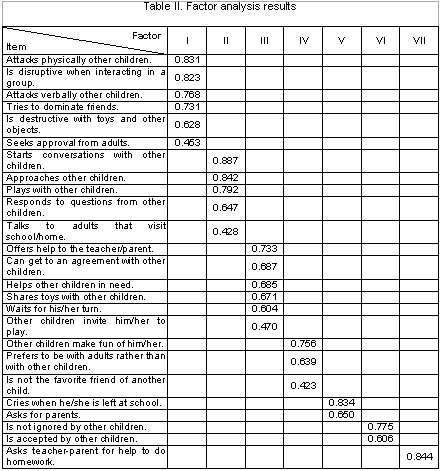

XII. Structure of the final version

Results reported above, provide some guidelines about the basis of the final version for the scale:

- It should collect information from both parents as well as teachers.

- Scores from parents and teachers should be weighted and the result should be the addition of both scores.

- A dichotomous yes/no response format would be more efficient to bring out the factors expected.

- The instrument intends to measure social competence of children through five different dimensions: Disruptive behavior, Social interaction, Cooperation, Acceptance and Attachment.

- Seven items are negative. This should be considered before coding. A general measure of social development should weight positive and negative responses.

- Items should be presented randomly without any label.

- Because of its recommended uses results will show in a profile of five different areas and also a general social development score.

XIII. Discussion

The ESDS has many potential uses in practical situations. It was not designed as a diagnostic instrument in the sense of fitting medical settings (DSM-IV criteria). However it provides information that many practitioners in schools and home or clinical environments may find useful. The following is a list of such applications:

- Knowledge of the child’s level of social development may aid parents, teachers and day care personnel in understanding the child’s behavior with other children or adults.

- Knowledge of the child’s social development may aid parents, teachers and day care personnel in finding the best ways to shape social behavior.

- Knowledge of the level of social development may help parents and teachers in understanding the risks of children for future adaptive and academic problems.

- Knowing the characteristics of the child’s social behavior may help others to be more tolerant of the behaviors the child exhibits.

- Knowledge of the level of social development may help parents, teachers and day care personnel to plan programs of intervention to prevent future problems.

- Evaluation of short and long term effects of intervention programs.

13.1. Research implications

Many different interesting questions arise in the social development area. One of these is the antecedents for the different levels of social development. Another possible area of research would be the characteristics of the social development of the child at age four as a predictor of later development outcomes. Yet another different area of research would be the use of social development as a mediating variable in studies in which relations with other variables are the primary interest, such as intelligence or temperament.

The changes in the resulting version of the checklists also need to be analyzed. The factor analysis may confirm the newly formed factors or suggest other further changes.

13.2. Administration and scoring

The following general guidelines for the administration of the checklist should be followed in order to help ensure the accuracy of the rating obtained:

- Both forms (parents and teacher) should be completed in an environment in which the rater is free to concentrate on the behavioral statements presented. This may preclude having the day care worker or teacher complete the form while supervising children at school or having the parent respondent attempt to complete the form while she/he has supervision responsibilities at home. Of course the rater’s sense of the level of distraction in the environment is variable.

- When multiple raters are used in one setting (e.g. both father and mother at home), the raters should complete the questionnaire independently. The researcher may wish to ensure independence by having the forms completed in his/her presence or by explaining the importance of such independence to the raters.

- Ratings on the parents or the teachers’ forms should be based on the behavior of the child during the last month. Even though the teacher or day care worker should have known the child for no less than three months.

- The assessor should make sure that the rater has read the instructions carefully before beginning to make the ratings. If there are any questions, the directions should be read to the rater and clarified.

- In cases in which the respondent cannot easily read the checklist, the assessor may present the questionnaire orally.

13. 3. Interpretation

The resulting scores from both checklists (parents and teachers) should be added for each factor individually and plotted in the given profile. A mark should be made in the corresponding number. In such a way, a general picture of the child’s social behavior will be depicted and those areas in which the child needs attention or coaching will be shown. From there a specific plan for each child can be derived when needed.

XIV. Disruptive behavior

References

Achenbach, T. M., McCanaughy, S. H. & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems. Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101 (2), 213-232.

Ainsworth, M. A. (1979). Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist, 34, 932-937.

Ainsworth, M. A. & Bolwby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46, 333-341.

American Educational Research Association. (1999). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, DC.

Asher, S. R. & Dodge, K. A. (1986). Identifying children who are rejected by their peers. Developmental Psychology, 22 (4), 444-449.

Asher, S. R., Singleton, L. C., Tinsley, B. R. & Hymel, S. A. (1979). Reliable sociometric measure for preschool children. New York: American Psychological Association.

Azmitia, M. & Hesser, J. (1993). Why siblings are important agents of cognitive development: a comparison of siblings and peers. Child Development, 64 (2), 430-444.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monographs, 4 (1, part 2), 1-103.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. London: Hogarth.

Brofenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of child development: Vol. 6. Six theories of child development. Revised formulations and current issues (pp. 187-249). Greenwich, CT: Jai Press.

Cohn, D. (1990). A child-mother attachment of six-year-olds and social competence at school. Child Development, 61, 152-162.

Coie, J. D. & Dodge, K. A. (1988). Multiple Sources of data on social behavior and social status: a cross-age perspective. Child Development, 59, 815-829.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A. & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557-570.

Coie, J. D. & Kupersmidt, J.B. (1983). A behavioral analysis of emerging social status in boy’s groups. Child Development, 54, 1400-1416.

DeRosier, M. E., Kupersmidt, J. B. & Patterson, C. J. (1994). Children’s academic and behavioral adjustment as a function of the chronicity and proximity of peer rejection. Child Development, 65, 1799-1813.

Dishion, T. J. (1990). The family ecology of boy’s peer relations in middle childhood. Child Development, 61, 874-892.

Dunn J. & Hendrick, C. (1982). Siblings: Love, envy and understanding. London: Grant McIntyre.

Fein, G. G. (1978). Play revisited. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), Social and personality Development. (p. 198-109). New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston.

García Coll, C. & Magnuson, D. (1988). Cultural influences on child development. Are we ready for a paradigm shift? Child Development, 59, 99-104.

Green, K. D., Forehand, R., Beck, S. & Vosk, B. (1980). An assessment of the relationship among measures of children’s social competence and children’s academic achievement. Child Development, 51, 1149-1156.

Harkness, S. & Super, C. M. (1995). Culture and parenting. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of prenting: Vol. 2. Biology and ecology of parenting (pp. 119-125). Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum.

Harper, L. & Huie, K. (1987). Relations among preschool children’s adult and peer contacts and later academic achievement. Child Development, 58, 1051-1065.

Harris, M. B. & Goss, D. (1988). Children’s understanding of real and apparent emotion. In J. W. Astington, P. L. Harris & D. R. Olson (Eds.), Developing theories of mind (pp. 202-207). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hartup, W. W. (1989). Social relationships and their developmental significance. American Psychologist, 44, 120-126.

Haviland, J. M. & Lelwica, M. (1987). The induced affect response: 10 week-old infant’s responses to there emotional responses. Developmental Psychology, 23 (2), 97-104.

Howes, C. & Phillipsen, L. (1998). Continuity in children’s relations with peers. Social Development, 7 (1), 340-349.

Lamb, M. E. (1978). Social and personality development. New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston.

Lieberman, A. F. (1977). Preschoolers´competencewith peers, relationships with attachmente and peer experience. Child Development, 48, 1281-1287.

Lieberman, M., Doyle, A. B. & Markiewics, D. (1999). Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late childhood and early adolescence: Associations with peer relations. Child Development, 70, 202-213.

McCoy, J. K., Brody, G. H. & Stoneman, Z. (1994). A longitudinal analysis of siblings relationships as mediators of the link between family process and youth’s best friends. Family Relations, 43 (4), 400-408.

Moreno, J. L. (1934). Who shall survive? Washington, DC: Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing.

Pellegrini, A. D. & Glickman, C. D. (1991). Measuring kindergartners’ social competence. ERIC Digest. ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED327314).

Petit, G. S., Dodge, K. A. & Brown, M. M. (1988). Early family experience, social problem solving patterns, and children’s social competence. Child Development, 59, 107-120.

Putallaz, M. (1983). Predicting children’s sociometric status from their behavior. Child Development, 54, 1417-1426.

Rubin, K., Bukowski, W. & Parker, J. (1998). Peer interactions, relationships and groups. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional and personality development (5ta. ed., pp. 619-700). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Sánchez Escobedo, P. (1986). Developmental psychopatology. The approach to the borderline case. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Iowa.

Seifert K. & Hoffnung, L. (1997). Child and adolescent behavior. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Sparrow, S. S., Balla, D. A. & Cicchetti, D. V (1984). The Vineland adaptive behavior scales. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing.

Stone, L. & Church. G. (1979). Childhood and adolescence. New York: Random House.

Strayer, J. (1986). Children’s attributions regarding the situational determinants of emotions in self and others. Developmental psychology, 5, 649-654.

Waters, E., Wippman, J. & Sroufe, L. A. (1979). Attachment, positive affect, and competence in the peer group: Two studies in construct validation. Child Development, 50, 821-829.

Wentzel, K. R. (1991). Social competence at school: Relation between social responsibility and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 61 (1), 1-24.

Zigler, E. & Trickett, P. K. (1978, September). IQ, social competence, and evaluation of early childhood intervention programs. American Psychologist, 33, 789-798.

Please cite the source as:

Aguiar, R., Sánchez Escobedo, P. & Satterly, D. J. (2005). A social development assessment scale for Mexican children. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 7 (1). Retrieved month day, year from:

http://redie.uabc.mx/vol7no1/contents-aguiar.html